The University of Oxford is home to an extraordinary collection of artworks, including a rich, numerous, sometimes magnificent and occasionally eccentric flock of portraits. Portraits are displayed around colleges and University buildings as commemorations of great academic, political, or artistic achievements, in gratitude to benefactors, or – sometimes – just through accidents of history; many of which have been digitised by Art UK.

Scrolling through these works, it's easy to feel a bit overwhelmed by the massed ranks of middle-aged and elderly white men wearing suits or academic robes – as in the gallery at the top of this piece. Oxford portraits are undeniably dominated by images of the white-skinned, upper-class, male, and often slightly stuffy: a reflection of many centuries of inequality and exclusion.

In the last few years, initiatives have sprung up at many colleges and departments to redress the balance, with newly commissioned paintings and photographs representing and celebrating the University's new diversity, and a new project, Diversifying Portraits, commissioning an exciting set of pictures of living Oxford individuals. But my research for this project has shown that the University's artworks, like its history, are less homogeneous than you might expect. I've found hundreds of portraits of diverse and fascinating people: scholars, world leaders, writers and artists.

Here are four Oxford portraits which break away from the stereotypes.

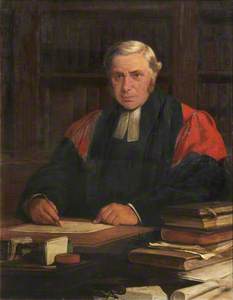

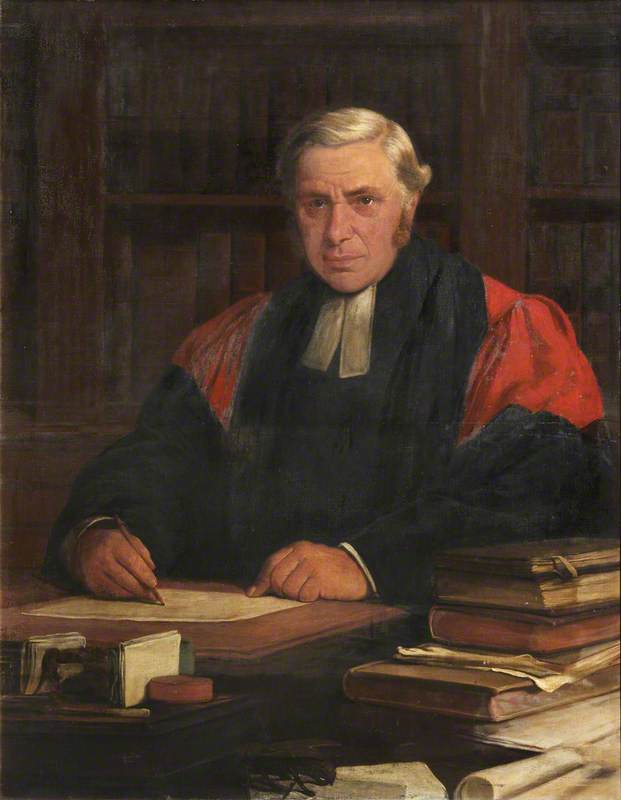

1. Sir Bhagavat Simhaji

In pose and style, there's not much to distinguish this portrait of Sir Bhagavat Simhaji (1865–1944) from many other nineteenth-century academic portraits to be found at the University (this one is owned by the Bodleian Library).

In a bright red gown, and holding some papers, he looks confident, scholarly, and somewhat formal.

More unusually, though, the sitter is wearing regalia which proclaims him to be not only the holder of a medical degree (from the University of Edinburgh in 1892), but also His Highness Maharaja Thakore Shri Sir Bhagvatsingh Sahib, Maharaja Thakore Sahib of Gondal. Simhaji was the ruling Maharaja of this princedom in Gujarat during his medical education in Britain, having come to the throne at the age of four when his father died.

He would become a progressive and modernising ruler, as well as an occasional medical writer and practitioner, cutting taxes and promoting education and rights for women.

2. Mary Honywood Waters

The inscription on this portrait explains that Mary Honywood Waters (1527–1620) lived to the age of 93, having had 16 children, 114 grandchildren, 228 great-grandchildren and nine great-great grandchildren, and 'led a most pious life'.

But leading a pious life, as a fervent Protestant in seventeenth-century England, was not as straightforward nor as domestic as this summary might sound. In the religious persecution during the reign of Mary I, Waters remained defiant and took the risk of visiting and writing to imprisoned Protestants. She went in person to watch the execution by burning of her friend John Bradford in 1555.

Her life was also emotionally turbulent: in her forties, she suffered from a drawn-out depression or crisis of faith that the writer Simeon Foxe described as 'a consumption through melancholy'. There's a famous story about her response to the optimistic advice of Simeon's father John Foxe offered to her:

All his counsels proved ineffectual, insomuch that, in the agony of her soul, having a Venice glass in her hand, she brake forth into this expression: 'I am as surely

The strong-minded Waters wasn't convinced by this incident at the

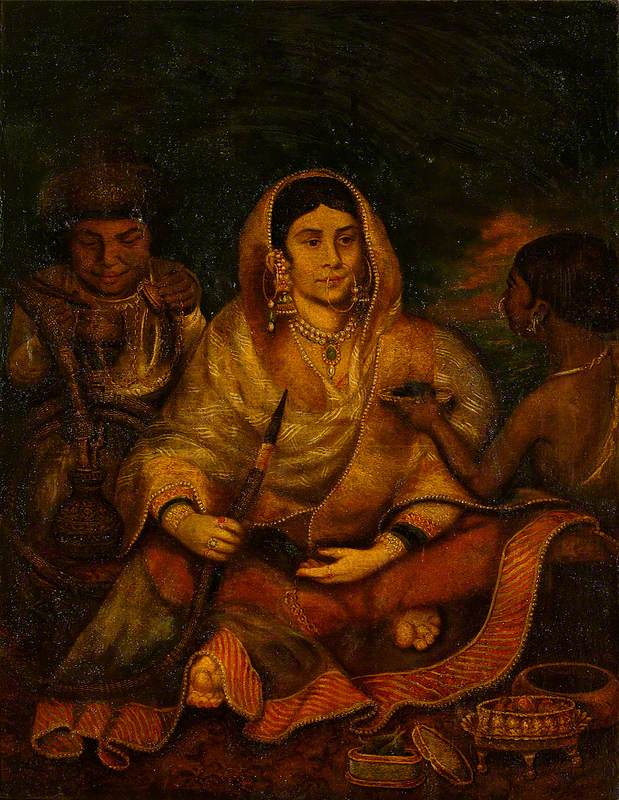

3. Isabella Arlosh

The unexpectedly romantic figure of Isabella Arlosh (1835–1905) can be seen in the dining hall of Harris Manchester College, together with paintings of her husband James and son Godfrey.

Isabella Arlosh (1835–1905)

(wife of James Arlosh and mother of Godfrey Arlosh)

William Salter Herrick (c.1807–1891)

Very little is known about the painting, or about Isabella, who (unlike many of the faces in the hall) was neither an academic nor a church leader, although the wealthy Arlosh family was Unitarian in religion and politically Liberal, campaigning in favour of reform in the late nineteenth century.

Tragically, in 1890, their young son Godfrey Arlosh, then an undergraduate at Brasenose College, was killed in a riding accident in Port Meadow; after which his grieving parents moved to Oxford and became benefactors to Manchester Unitarian College in his memory. When they died within a fortnight of each other in 1904, they left the college a large estate which was used to fund its development in the twentieth century.

4. The workforce of All Souls College

The artist Benjamin Sullivan spent more than three years on this huge three-part painting of the non-academic staff of All Souls College, completed in 2012. Some of the designs, sketches and studies he produced can be seen on his website.

The triptych, which was influenced by medieval religious art as well as the more recent work of Stanley Spencer and David Hockney, is packed with 27 individual portraits, and many meaningful or symbolic details: a jar of Marmite in a still-life on the kitchen table, a row of ducklings waddling past in the bottom-right corner, a distant robed graduate in the High Street in the background.

It acts, the artist writes, as 'a token of recognition' for the college 'of how much it depends upon and cherishes the people who work in it', as well as a statement which 'expresses confidence in the power of art.'

Dr Ruth Scobie, Early Career Research Fellow at TORCH and Project Manager of Diversifying Portraiture

Find out more at the Oxford University Diversifying Portraits website and follow @DivOxPortraits on Twitter

.jpg)