A new film called The Duke starring Jim Broadbent is not, as some may think, a film featuring John Wayne, but recounts the fascinating tale of the theft of Francisco de Goya's portrait of the Duke of Wellington from The National Gallery – and the intriguing motivation behind it. This theft occurred on 21st August 1961. By a quirk of dates, 50 years previously, on 21st August 1911, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre.

The theft of the Goya painting was carried out by a 65-year-old retired truck driver Kempton Bunton and his motivation was not for monetary gain. Bunton had been angered by the recent auctioning of the painting. Not the selling of it but the price paid. A bid for the painting by the New York collector Charles Wrightsman of £140,000 was the highest bid at auction but he let the Wolfson Foundation purchase it for £100,000 so it could go to The National Gallery. This forced the Government to pay £40,000 to the collector which saved the painting from export and created headlines.

Bunton's reason for the stealing of the painting was simple – to hold it to ransom for £140,000 which he said should be given to the elderly, particularly war veterans and other people in financial need, and specifically for paying for television licences. Bunton himself had been in prison for refusing to pay the licence fee – an issue that is still in the news today.

The painting was held for four years, even making an appearance in the first James Bond film Dr No in the villain's lair in 1962. Its story was rather less glamorous in real life, and it was returned minus the frame in a left luggage area in New Street Station. The rest of this story I will leave for you to discover yourself while we take a closer look at Wellington's depiction in art.

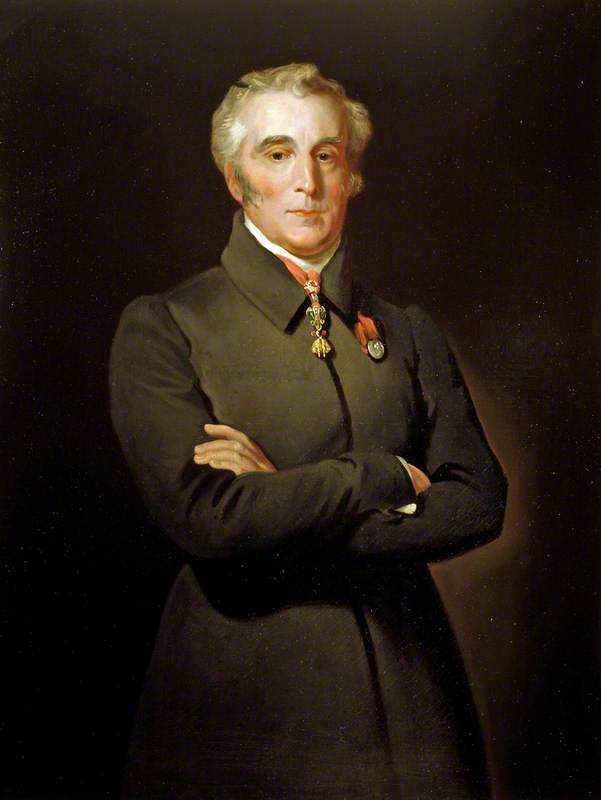

Arthur Wellesley (1769–1852), 1st Duke of Wellington

c.1815–1816

Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

The man who is today best known as the 1st Duke of Wellington was born Arthur Wellesley in 1769 in Dublin, to an Anglo-Irish aristocratic Protestant family. He was the sixth of nine children born to the Earl and Countess of Mornington, and his elder brother was Richard Wellesley, later the 1st Marquess Wellesley.

Arthur Wellesley joined the army in 1787, as a commissioned officer in the infantry. It was common practice for wealthy officers to purchase commission, and he rose through the ranks in this fashion. Thanks to some help from his brother, he also served at Dublin Castle as aide-de-camp to two successive Lords Lieutenant of Ireland.

Wellington is perhaps unique among generals of that period due to his long career, mostly in the public eye. His life was captured at all stages by artists. As well as the lauded victor of the Battle of Waterloo, today it is often forgotten that he also served as Prime Minister, between 1828 and 1830 and for a short period in 1834.

Here we have a less formal but still highly stylised painting of Wellesley by Goya – in this, he is portrayed almost like a matador.

Equestrian Portrait of the 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852)

1812

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

Examination of this painting has shown that indeed this was a different portrait but had the Duke's head added. It was painted in only three weeks in 1812, such was Goya's wish to please.

By the time this was painted Arthur Wellesley was a well-known military figure. He had fought at Flanders in 1794 and directed the campaign in India in 1796 against the 'Tiger of Mysore', Tipu Sultan. It was the campaigns and his organisation in India that made his name recognised.

Wellington was not, however, just a military commander. He also had a parliamentary career, first serving as an MP in the Irish House of Commons, and then being elected as a Westminster MP for Rye in 1806. But it was his engagements against his nemesis Napoleon (who was born in the same year) and the French that would define his life and memorialise him in history.

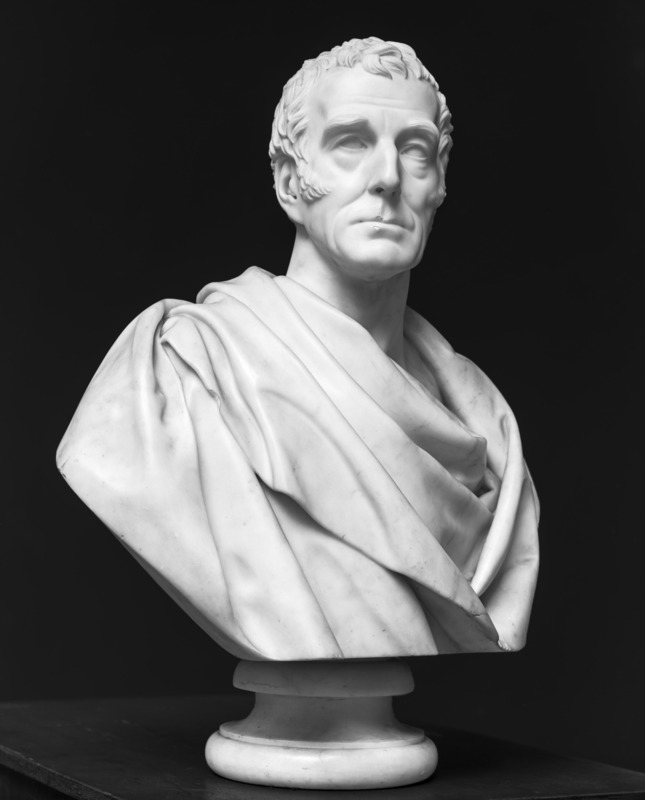

The 1st Duke of Wellington Looking at a Bust of Napoleon

Charles Robert Leslie (1794–1859)

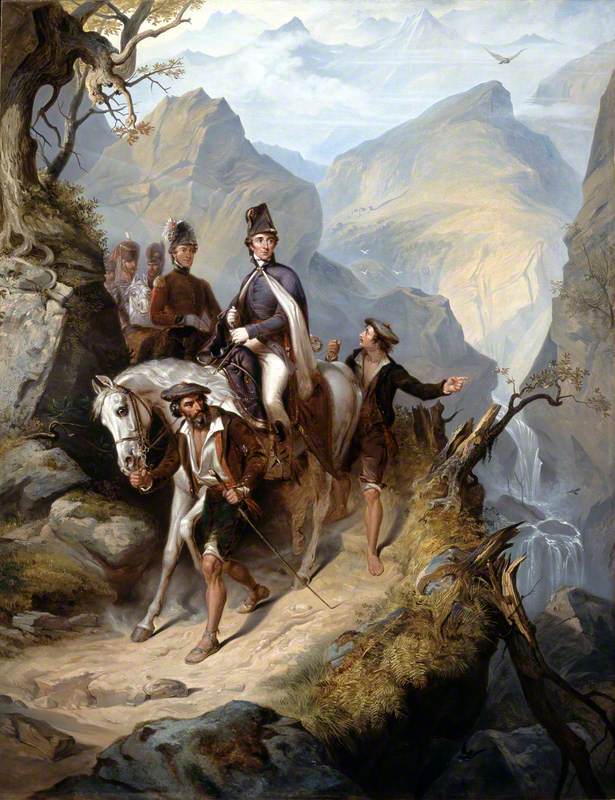

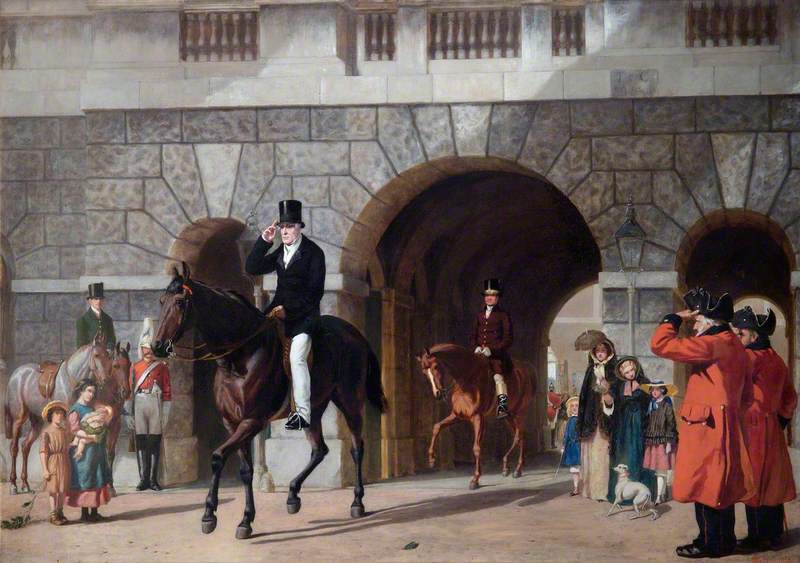

In this painting by Thomas Jones Barker, we have a youthful Wellington on a white horse, being led through a mountain pass in Spain leading towards the Battle of the Pyrennes, an action in the Peninsular War.

This war, which was fought in Portugal and Spain against the French and captured memorably in print by Bernard Cornwell and his sublime series of Sharpe books, would engage Wellington from 1807 to 1813. In 1814 he was created the Duke of Wellington.

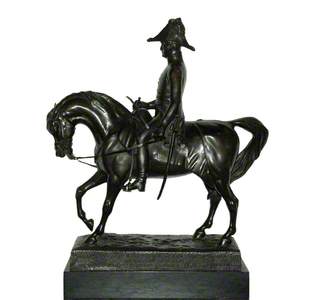

Duke of Wellington (1769–1852)

Joseph Edgar Boehm (1834–1890) and Howard Ince and Moore & Co. and Alexander Macdonald & Co. (active c.1820–1941)

He would engage with Napoleon one more time – at the Battle of Waterloo on 18th June 1815.

The Battle of Waterloo: The British Squares Receiving the Charge of the French Cuirassiers

1874

Félix Henri Emmanuel Philippoteaux (1815–1884)

These paintings offer insights into the realities of battles of this period with its smoke-filled battlefields and the wounded. It is estimated that in total 62,000 men were killed in this one battle. As Wellington famously stated:

'My heart is broken by the terrible loss I have sustained in my old friends and companions and my poor soldiers. Believe me, nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.'

Almost immediately after the battle, tourists began visiting the scene.

The Duke of Wellington Describing the Field of Waterloo to HM George IV

1840

Benjamin Robert Haydon (1786–1846)

Wellington bought Apsley House in 1817, where the Wellington Collection can be viewed today, and wished to settle into civilian life. He forged his way in the political field and became Prime Minister in 1828. In 1829 his great political achievement was to achieve Catholic emancipation. He was, however, a harsh and very conservative Prime Minister, stamping down on the Reform movement. His home was attacked twice, so iron bars were installed on the windows, gaining him the nickname of the 'Iron Duke'.

Wellington was also often depicted in old age, he never faded from public view although he retired from public life in 1846 at the age of 77.

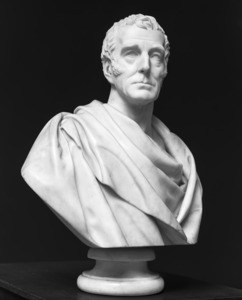

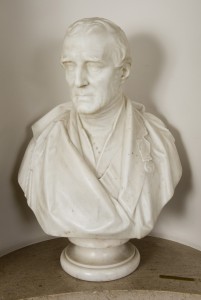

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

1845

Alfred d'Orsay (1801–1852)

Two years later he was approached and agreed to organise the defence of London in 1848 against the possibility of a Chartist uprising. He stationed cavalry and infantry at the south side of the bridges over the River Thames and had cannon readied near Buckingham Palace. Due to rain, the expected number of demonstrators failed to turn up – this is said to have ended the Chartist movement. There can be no doubt that the 80-year-old Wellington would have approved action against the protestors if he thought it necessary.

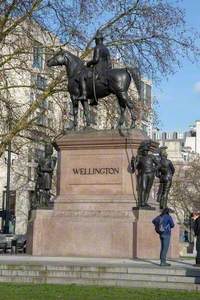

The Duke of Wellington (1769–1852)

1844–1849

Abraham Solomon (1823–1862)

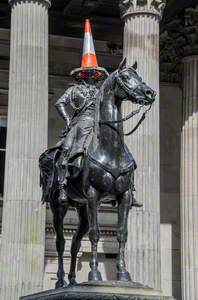

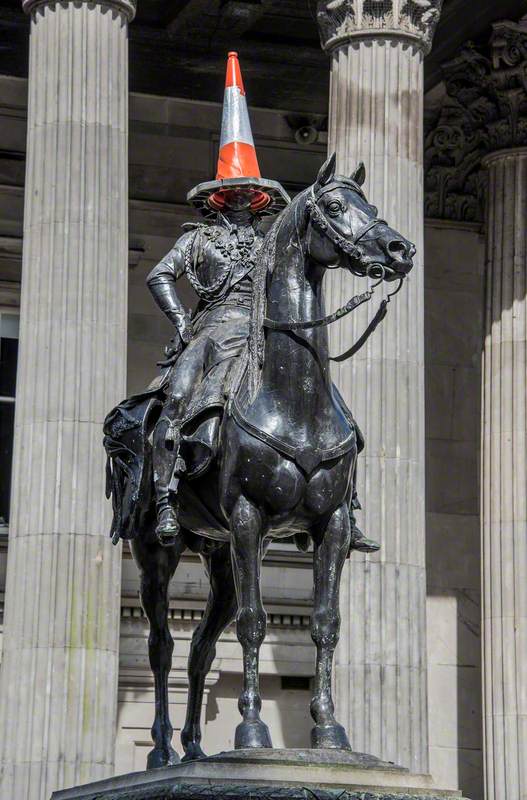

It's doubtful therefore he would have approved of this use of his statue in Glasgow, with the locals making sure there's always a traffic cone crowning the duke.

Equestrian Monument to the Duke of Wellington

1840–1844

Carlo Marochetti (1805–1867) and Soyer and De Braux and James Smith (1808–1863)

During his first tenure as Prime Minister, Wellington was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a position he held from 1829 to 1852. The residence that came with the position was Walmer Castle in Kent, where he stayed each year from August to November. Wellington died at Walmer Castle in 1852.

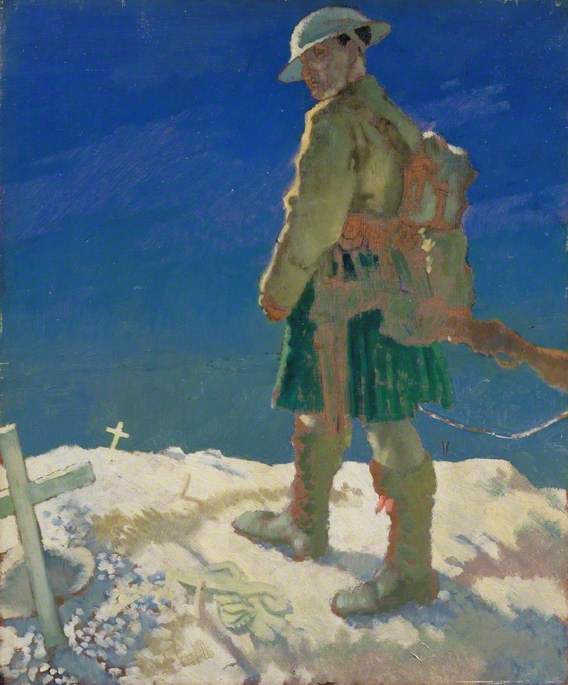

His Last Return from Duty

1853

James William Glass (1825–1855)

The largest monument to Wellington is, of course, Wellington Arch in London. This was commissioned in the 1820s to mark Wellington's victories against the French. It originally served in 1830 as an entrance to Green Park (and known as the Green Park Arch) and an outer entrance to Buckingham Palace.

Eight years later it was decided that a large national memorial to the Duke of Wellington should be placed on top of it and the arch had to be strengthened.

250 years ago today, the Duke of Wellington was born. #Wellington250

— English Heritage (@EnglishHeritage) May 1, 2019

Did you know that a statue honouring him as one of the great heroes of his time once sat on top of what's now Wellington Arch, and that the arch hasn't always been in the same place? https://t.co/dBbNGiRNi6 pic.twitter.com/gg3sAvVNfY

The statue was made from bronze from captured French cannons. The statue was derided as not being in scale with the arch and when the arch was moved due to the increase in traffic in the 1880s the statue of Wellington was moved to Aldershot.

Wellington Arch and Quadriga

1825–1912

Adrian Jones (1845–1938) and A. B. Burton (active 1874–1939) and Decimus Burton (1800–1881)

The statue of a quadriga, a boy driving a four-horse chariot, accompanied by Peace now adorns the top of the arch today. This was sculpted by Adrian Jones and erected in 1912 and unveiled with no ceremony.

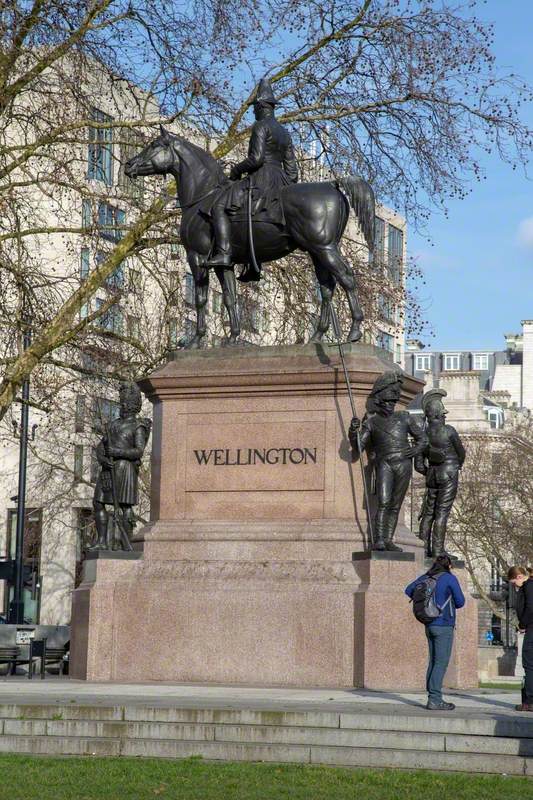

My own favourite artwork regarding the Duke is this statue by the artist Sir Francis Leggatt Chantrey which stands in front of the Royal Exchange.

Duke of Wellington (1769–1852)

1837–1844

Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781–1841) and Henry Weekes I (1807–1877)

Mounted, he seemingly orders and directs commuters around London of a morning and evening. Chantrey died before it was completed and his assistant Henry Weekes completed the work, which was unveiled on 18th June 1844, the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo.

I have vivid memories of staring up at this statue when a schoolboy and being told that the artist who made this killed himself out of despair as the figure was lacking a saddle and stirrups. Although these items are indeed missing, the story is just a myth!

In all the depictions of the Duke of Wellington, there is a sense of solidity. An image of a man who knew his own mind. This was valuable on the battlefields of Europe in the nineteenth century and in the political world. However, one wonders how history would have judged him if the Chartist uprising had happened.

It is perhaps rather fitting that a portrait of the Iron Duke was stolen not for monetary gain, but to highlight the plight of the poor and needy in the twentieth century. Perhaps – just perhaps – Arthur Wellesley would have admired the bravado of Bunton.

Gary Haines, archivist and researcher