During the time of the eighteenth-century French court, pink was a popular choice for paintings, fashion and decorative arts. The richest and most influential people in the country were enveloped in rose, salmon and coral hues.

The colour was adopted by royals and trendsetters, men and women alike. Pink was an emblem of wealth since the majority of the population would not have dreamt of affording to dress in pink or eat brioche from a pink porcelain plate. Business was made in pink, from the commissioning of court artists to paint in pink, to factories being founded to produce luxurious goods in pink.

Pink was power. Its popularity spread from France – the era's global centre of fashion – across western Europe by wealthy men and women, who favoured the colour for their gowns and embroidered silk coats. Pink spread, to all rich enough to not be left out of the trend, into rooms and onto clothes.

Today we might associate the colour pink with softness and femininity but 300 years ago, feelings about the colour were different. (In fact, if there was a 'female' colour during that time, it was green.) Back then, pink signified aristocracy, not femininity. One of the most powerful men in the mid-eighteenth century, Louis XV, King of France, was an advertisement for the craze. He enjoyed pink ornaments – this sumptuously decorative musical clock, inlaid with salmon-coloured silk, was possibly made for the king.

Musical Clock

c.1762, gilt bronze, silk, glass, brass, enamel & steel, design attributed to Jean-Claude Chambellan Duplessis the elder (c.1695–1774)

The colour was a particular favourite of Madame de Pompadour, mistress to Louis XV and possibly the most influential woman in French court history. Not the wife of the King but still the Queen Bee, Madame de Pompadour and power were one and the same. Since a child she was nicknamed 'Reinette', meaning 'little queen'.

Mistress and advisor, she had an incredible hold over the Louis XV and a great influence on politics – it is said Pompadour started wars and sent more men to the Bastille than any French king. Foreign policy and international affairs aside, she wielded a remarkable control over visual culture with impeccable effect. Her favourite colour, Pompadour pink, became one of Rococo's definitive shades.

The deliberate use of pink as a focal colour of a painting was made possible by the discovery of brazilwood in South America (Brazil's namesake) in the eighteenth century. The plant yielded a new dye that gave a brighter and long-lasting pink. Before this, pink was seen as a pale shade of red rather than a colour in its own right.

Pompadour commissioned paintings from François Boucher that utilised pink as the central colour. In The Rising… and The Setting of the Sun, the figure of Apollo – who is thought to represent Louis XV – is draped in pink fabric. Here, pink is not gendered female but instead associated with the same godly power the rulers of the ancien régime bestowed themselves.

Painting was not the only art to flourish during the Rococo. The Vincennes porcelain manufactory was established in 1740 in the disused Château de Vincennes to the east of Paris. In 1756 the manufactory moved to Sèvres to the southwest of the city to be en route from the French court of Versailles to the French capital of Paris. From the beginning, Louis XV financed the company and by 1759 entirely owned it. Madame de Pompadour invested her attention to see the company thrive and oversaw that Versailles courtiers and Parisian bourgeoisie would buy from the company for its financial growth.

Covered Jug and Basin

1758, soft-paste porcelain painted & gilded with a silver-gilt thumbpiece by Manufacture de Sèvres

In line with the times, one of the most produced ground colours of Sèvres porcelain was Fond Rose. At this time, pink was praised for its uplifting effect on men and was recommended as the decorative colour of choice for a gentleman. Therefore, the colour penetrated interiors and decorative arts alongside fashion and painting.

Pot-pourri Vase and Cover (Vase 'pot pourri Hébert')

c.1760, soft-paste porcelain, painted & gilded by Manufacture de Sèvres – Pierre-Joseph Rosset (1734–1799) & attributed to Jean-Louis Morin (1732–1787)

Pompadour would give Vincennes porcelain as international diplomatic presents and, very shrewdly, to particularly helpful friends such as the minister of police who acted as her spy at court. For personal use, Louis XV tended to buy more blue ground, whereas Pompadour favoured green ground (rather than pink, surprisingly). The porcelain would have many functions, from little egg cookers to clothes brushes. Every object for the hands of the well-to-do needed to be delightful. Potpourri pots were repeatedly produced and avidly purchased from the factory. The pots were filled with petals to scent through the small holes and give Versailles apartments a floral pink aroma.

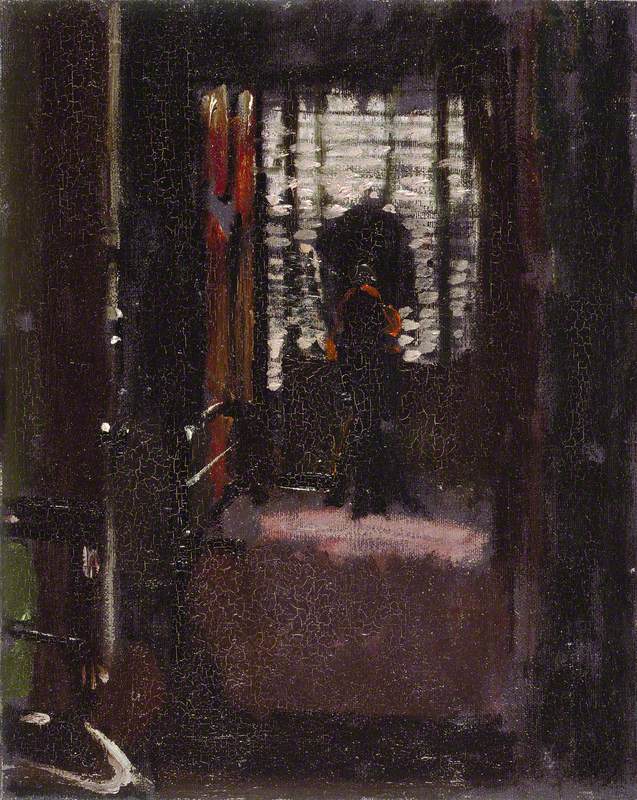

Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour

1750 with later additions, oil on canvas by François Boucher (1703–1770)

Dressed in head to toe in pink, with rosy cheeks dusted on from a porcelain pot, Madame de Pompadour was ready for a day of whispering ideas into the King's ear. Blush on a Caucasian woman simultaneously suggested innocence and sexuality – it was used by, and is now associated with, both eighteenth-century courtiers and prostitutes. Portraits of Madame de Pompadour drew attention to her coquettish cheeks, which were illustrated to please the King. She may have appeared to blush in her portraits, but Madame de Pompadour did not have a tender temperament and was wise to the ways a woman may exert some power over the men who tried to keep her down. In fact, even a dull and disapproving member of the Queen's party, the Duc de Luynes, permitted her 'fort jolie'. Beauty was an asset for impact.

Meanwhile in England, superstar London society hostess Maria Coventry, Countess of Coventry, had such a taste for the popular makeup trend of powdered white skin and pink cheeks that she became ill from lead poising (her portrait is shown on the far left of this eighteenth-century folding fan). The Countess's illness only led to her greater use of her makeup until it was the death of her. The poor woman died for beauty, fashion and pink because this was sadly necessary to capture the public's admiration.

Pink could be outrageous. The famous Rococo painting The Swing (Les Hasards heureux de l'escarpolette) by Jean-Honoré Fragonard is an erotic use of pink. Underwear was not worn under such dresses as modelled in the painting. Contemporary viewers would have understood that the man below to the left would have had a shocking view. This artwork has recently received restoration and the colour now appears a cooler, lighter and more vivid pink.

Comparisons can be made between the pink dress of the nameless protagonist of The Swing and the dress worn by Madame de Pompadour in a famous portrait by Boucher about 8 years before, which is supported by similarities in the scenery behind. This lends to the idea that the woman in the painting is a clever mistress who knows exactly what she is doing when she coyly kicks off her shoe into the air.

Marie Antoinette (1755–1793), Queen of France, in a Court Dress

1773

François Hubert Drouais (1727–1775)

Paris and the French court were the capital of fashion in Europe, disseminating trends through little fashion dolls wearing miniature gowns sent out in Europe about once a month, acting as magazines. The silhouette of the dress hardly changed for most of the century: the fabric, colour and trimmings made the fashion. Rose Bertin, modiste (milliner or dressmaker) to Marie Antoinette, was known as the Minister of Fashion, ensuring that Louis XVI's Queen of Fashion was dressed in the most contemporary trimmings.

The pink Rococo dress still holds inspiration for modern fashion designers with the unforgettable look often reimagined by the likes of Vivienne Westwood and Dior.

Doutzen Kroes at Christian Dior Fall 2007. pic.twitter.com/H5mFBLpLaI

— HCM (@hoodcouturemag) July 16, 2018

Flora Yukhnovich, known for her contemporary interpretation of the Rococo painting style, uses the colour pink lavishly to revitalise the style and its scenes. Pink-tinted clouds and characters draped in pink are given a breath of twenty-first-century air.

Whilst pink is a very Rococo colour, experimenting with the hue incites different interpretations for a modern viewer. Today, pink could almost be seen as a controversial colour, loved by some but considered sickeningly sweet, young and girlish by others. The way in which colour associations can prohibit the enjoyment of art in its many forms can be confining. Yet, in light of this, there is a new freedom to bend these norms and reclaim narratives through art and colour. Whilst pink embodied privilege in the eighteenth century, in the twenty-first century the colour can subvert power.

Tegan Huskinson, Collections Assistant at Art UK

Inspired by the research of The Wallace Collection and of Dr Valerie Steele, director and chief curator at The Museum at FIT.