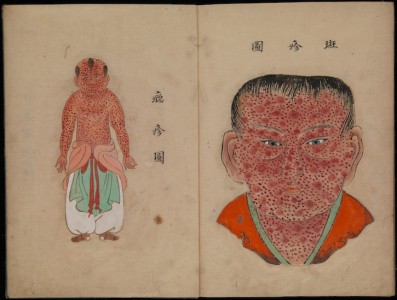

During the medieval and early modern periods, countries all around the globe were ravaged by plague, so much so that the fear of losing a family member or a friend was constantly at the backs of people's minds. People even died in the streets – creating great trauma and potentially affecting the rest of the population.

A Physician Wearing a Seventeenth-Century Plague Preventive Costume

unknown artist

As there was no remedy, and as the death rate was extremely high, for centuries the plague was seen as one of the worst enemies of the people. The Black Death – which reached its peak in Europe from 1347 to 1351– resulted in the deaths of up to 75–125 million people worldwide.

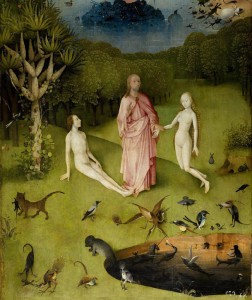

The Plague at Ashdod

(after Nicolas Poussin) 1631

Angelo Caroselli (1585–1652)

Centuries later, septicemic, pneumonic, and bubonic plagues still ravaged countries, terrifying the general population. Back then, being diagnosed with the plague was almost certainly a death sentence.

A Cart for Transporting the Dead in London during the Great Plague

19th C

George Cruikshank (1792–1878) (by or after)

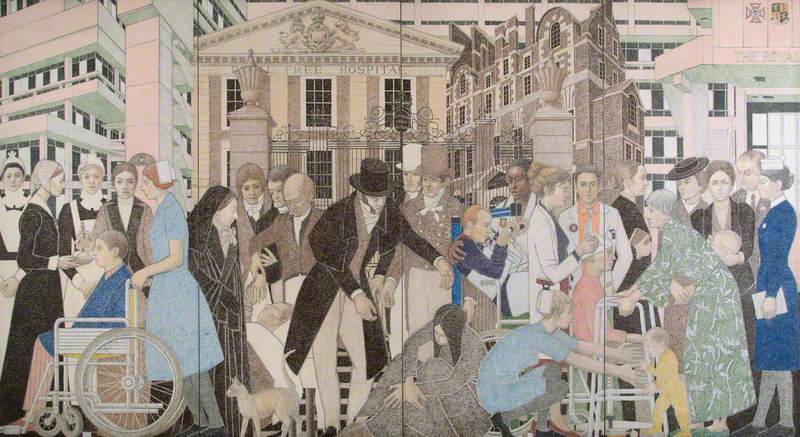

In seventeenth-century Europe, several countries continued to be ravaged by the disease. In London, the Great Plague lasted from 1665 to 1666 and killed an estimated 100,000 people in just 18 months.

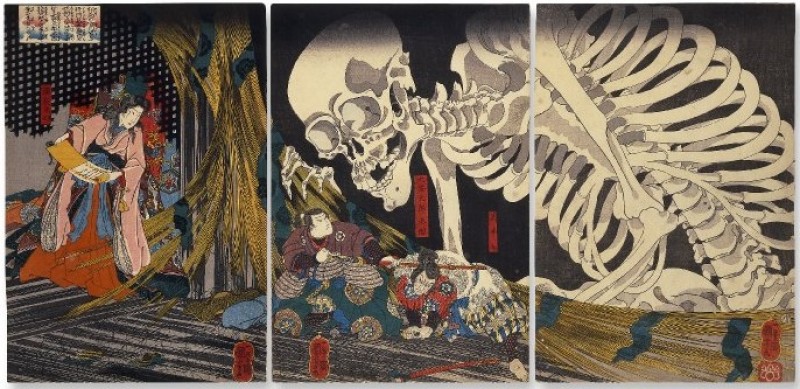

Many works of art have represented the Great Plague, and continue to do so even centuries after it happened. Every epidemic that ravaged Europe during the early modern period profoundly affected the mindset of the people. Life was ephemeral.

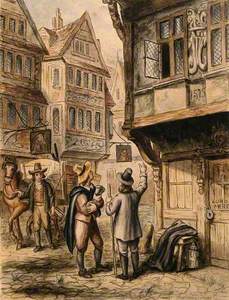

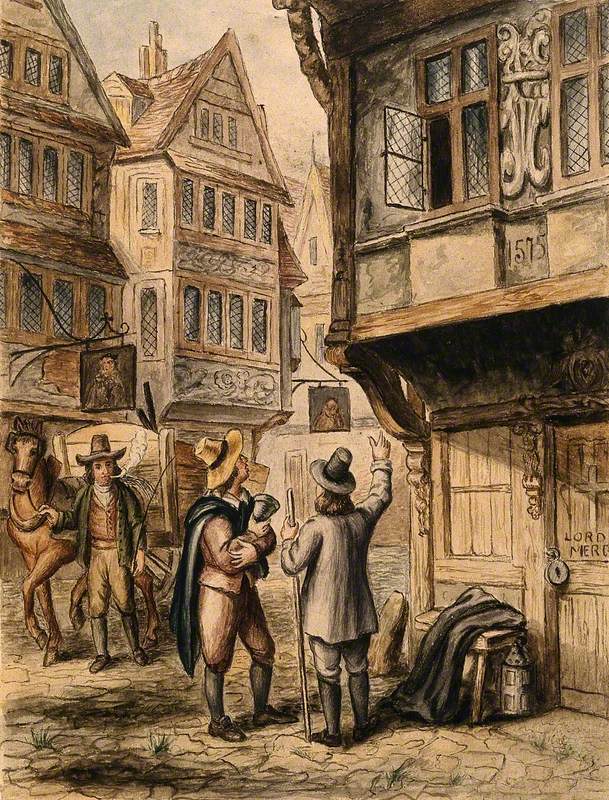

As portrayed in the picture below, a sense of desolation and despair was common among people during these times, and most paintings representing the plague leave the viewer with a deep gloomy feeling.

A Terrified Man Realising He Has Just Contracted the Plague, Surrounded by a Group of People

Edward Matthew Ward (1816–1879)

As the death toll continued to rise, no remedy was found against the disease. All anyone could do was remove the corpses to prevent the virus from spreading further and killing even more people.

For doctors – or physicians as they were called during the early modern period – this situation was unbearable. However, in the midst of the chaos, a man came up with a new invention, one that would possibly help protect the physicians treating patients who'd contracted the plague.

In 1619, the bubonic plague erupted in Paris, and an experienced French physician named Charles Delorme was about to have an idea. He created the 'plague preventive costume', which consisted of a long overclothing garment (Moroccan), which went from the neck all the way down to the ankle, the idea being that the air could not penetrate it. The outfit also consisted of gloves, boots, and a hat, which was made of waxed leather.

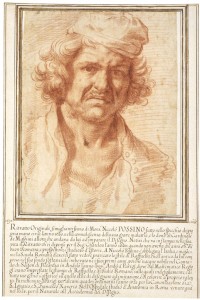

Charles Delorme

1630, etching on paper by Jacques Callot (1592–1635)

The hat was not truly part of the costume per se; it was more of a symbol of the physician's position as a medical practitioner. There was also a mask which had a 'nose half a foot long, shaped like a beak, filled with perfume with only two holes, one on each side near the nostrils, but that can suffice to breathe and to carry along with the air one breathes the impression of the drugs enclosed further along in the beak'. The eyes were also protected with spectacles. With this outfit, Delorme (and soon, other physicians) could attend to patients who needed their assistance.

A Physician Wearing a Seventeenth-Century Plague Preventive Costume

c.1910

unknown artist

During the 1619 French plague, Delorme was seen as a hero, assisting as many people as he could. His costume received a lot of praise and recognition, and soon his name was associated with the term 'the beak doctor'.

Even a century later, the costume – which had been tweaked to fit for purpose – was still being used by doctors in France and Italy. In the picture below, we can see a modified version of the costume being used by doctors during the Great Plague of Marseille in 1720.

While the costume itself did not strictly help to cure or prevent the spread of the plague, it remains an iconic outfit to the point where, for generations, it has become a staple of Italian commedia dell'arte and of carnival celebrations – and still is, even to this day.

A Physician Wearing a Plague Preventive Costume in Marseille, 1720

20th C

unknown artist

But who was Charles Delorme, apart from the inventor of the plague preventive costume?

Charles was the son of Jacques Delorme, a professor at the University of Montpellier who had great connections among the nobility. Charles followed in his father's footsteps and, in 1607, he graduated from the University of Montpellier at the age of 23. Soon after, he moved to Paris to practise medicine under the mentorship of his father. His reputation as a good practitioner grew rapidly in the capital and, thanks to his father's connections, Charles became the personal physician to several members of the Medici.

His prowess as a physician preceded him and he became the chief physician to three consecutive French kings: Henri IV, Louis XIII, and Louis XIV. Charles's benevolence was praised by Henri IV himself, as the physician was known for refusing special gifts offered to him by patients who came from nobility.

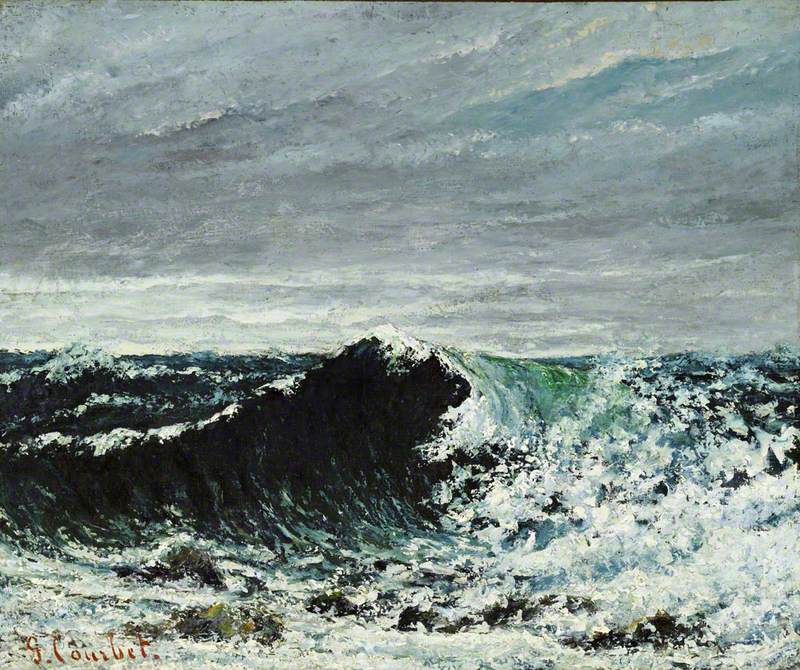

The Union of Henri IV and Marie de Médicis

1628

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

During Louis XIII's reign, Delorme's reputation continued to grow. Charles assisted Cardinal Richelieu a few times when he was feeling unwell, who then recommended the physician to most of the nobles at court and beyond. Before long, it was not unusual for Delorme to be asked to look after and cure nobles all around France.

Charles's service to the royal family and to the court was rewarded once more when, at the death of Louis XIII, he kept his position as chief physician under Louis XIV.

His costume invention is probably the main reason why he is still remembered today, but it is worth mentioning that Charles Delorme marked his time by serving three French kings and their respective courts.

Louis XIII (1601–1643), King of France

c.1650

Philippe de Champaigne (1602–1674) (after)

He built up his reputation as being a reliable, benevolent, and competent physician who cared about his patients and who found solutions during times of hardship. Desiring to improve people's lives, Charles spent a good deal of his time coming up with remedies for such diverse ailments as stomach pain and headaches.

He was more than just the inventor of the plague preventive costume; he was a talented physician who treated thousands of people during the reigns of three different French kings.

Estelle

Further reading

Joseph Patrick Byrne, Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues, ABC-Clio, 2008

Dorothy Crawford, Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped Our History, Oxford University Press, 2018

Howard W. Haggard, From Medicine Man to Doctor: The Story of the Science of Healing, Courier Dover Publications, 2004

Michel Tibayrenc, Encyclopedia of infectious diseases: modern methodologies, Wiley-Liss, 2007