From the 1990s onwards, the Portuguese-British artist Paula Rego worked almost exclusively in pastels. These sticks of ground pigment gave her an urgency and bodily connection that eluded the meticulous and somewhat removed process of working in oils or acrylic.

'With pastel you don't have the brush between you and the surface,' she explained, 'Your hand is making the picture. It's almost like being a sculptor...' Yet Rego was one of few prominent contemporary artists who worked mainly in pastel. This medium, frequently used by Old Masters and associated especially with women artists and sitters, draws her work into dialogue with the multifaceted, gendered legacy of pastels

The first President of the Royal Academy, Joshua Reynolds, once dismissed the pastellist Jean-Étienne Liotard, writing 'his pictures are just what ladies do when they paint for amusement.' By the eighteenth century, pastels were newly available in a wide range of colours. Portable and blendable, they became a favourite medium among professional eighteenth-century portrait artists, as well as amateurs. These artists were expanding the technical possibilities of pastels, taking advantage of their velvety depth of colour to produce sumptuous portraits that rivalled traditional media. This posed a threat to established painters like Reynolds, who drew on their association with women and amateur artists to denigrate the medium.

Gustavus Hamilton (1710–1746), 2nd Viscount Boyne

1730–1731

Rosalba Giovanna Carriera (1673–1757)

Some of the medium's earliest and most famous adopters were women artists, from Rosalba Carriera to Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. Certain contemporaries even drew comparisons between the powdery finish of pastel portraits and the made-up faces of the upper-class female sitters that they often depicted.

Due to their comparative speed and ease of use, artists recommended using pastels for portraits of those who were short on time or found posing taxing, especially children. For pastel artists, the medium was fast, flexible and capable of delivering intense colours. For detractors, it was facile and amateurish – suitable only for women and children.

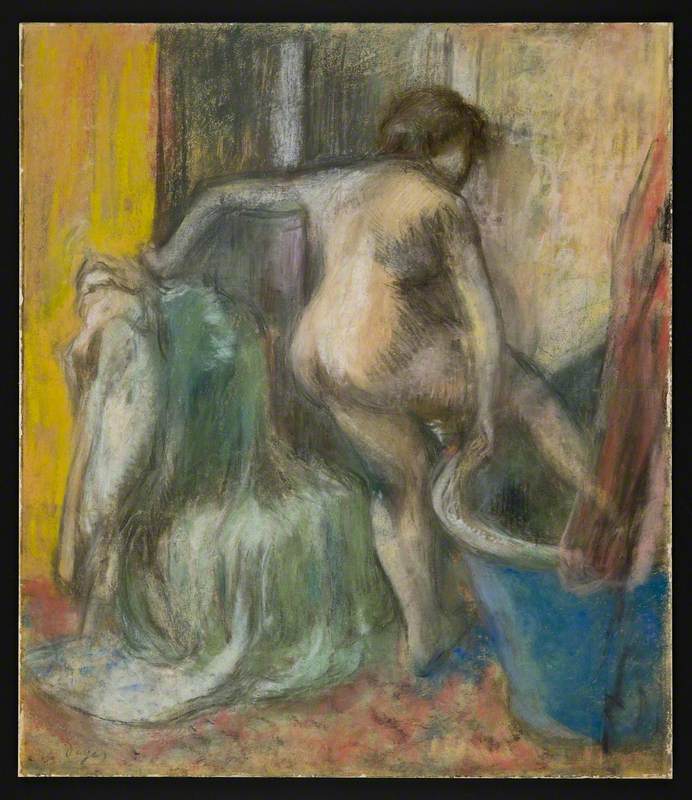

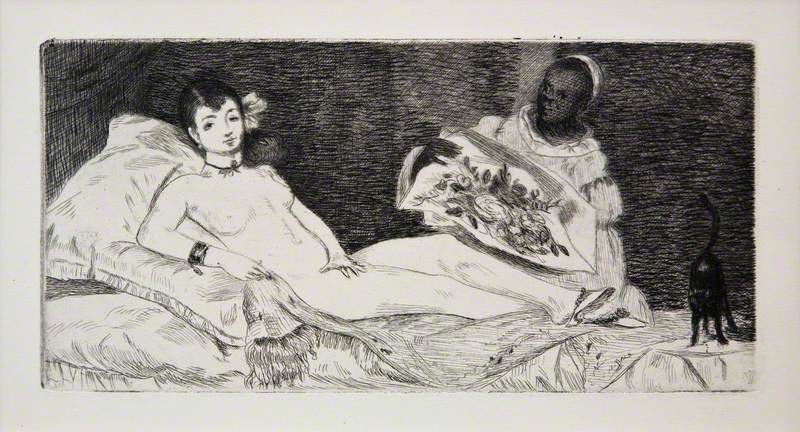

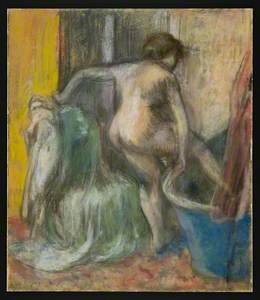

By the nineteenth century, the Impressionists and their predecessors were exploring new uses for pastels, capitalising on their spontaneity to draw directly from life in bold, sketch-like compositions. Yet they still retained some association with women artists and subjects. Their chalky finish made them ideally suited to Edgar Degas's intimate toilette drawings, and later the pallid faces of Toulouse-Lautrec's nightlife scenes.

Jane Avril in the Entrance to the Moulin Rouge, Putting on her Gloves

c.1892

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

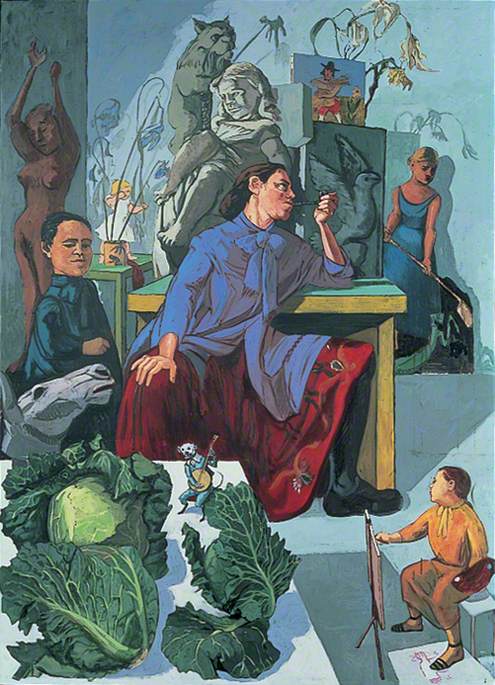

There is some irony, then, in Rego's turn to pastels. Rego created ambivalent, dreamlike works that lay bare women's experiences and interior worlds. She grounded her work in techniques and compositions that recall Old Master painters, especially following her time as artist-in-residence at The National Gallery in 1990. In her words, 'I wanted to be in the big boys' club, with the great painters I admired.' Just as she sought to bring a woman's viewpoint into Western art, she, perhaps unwittingly, co-opted a medium at once known for its Old Master inheritance yet associated with women artists. Rego's work draws on the contradictory nature of pastel, at once powdery and refined, capable of highly blended effects, and raw and immediate, retaining the traces of the artist's hand.

Above all, this is seen in her 'Abortion Series' of pastels from 1998. Each work trains the viewer's attention on one woman alone, contorted in animal suffering, or defiantly meeting their gaze. Clinical and claustrophobic, this series was made after a referendum failed to legalise abortion in Portugal. Rego explained, 'It highlights the fear and pain and danger of an illegal abortion, which is what desperate women have always resorted to.'

Fear and physicality are communicated through her raw application of pastels. Like in her first pastel series known as 'Dog Woman' (1994), the 'Abortion Series' has a sketchy finish, reminiscent of Edgar Degas's Bathers, dissolving nude women into bold taches – a central inspiration for her earliest work in this medium. Rego co-opts the immediacy and voyeurism of Degas's pastels to subversive new effect in the 'Abortion Series'.

In Triptych (2008), for example, Rego similarly applied her pastel pigments in violent hatchings, resembling claw marks. To preserve this effect, she built up her works from hard pastels that provide more resistance, to soft ones on the upper layers, which deposit more pigment with less effort. She subverted traditional techniques of blending, instead advising 'never smudge.' Favouring a harsher application, she fixed each layer to leave the traces of her hand visible in the work. Allowing for a layered depth of colour that is akin to Old Master painting, yet more bodily, immediate and violent, Rego had found her medium.

The artist described how vivid pastel colours seduce the viewer into confronting her most painful subjects: '…what you want to do is make people look, make pretty colours and make it agreeable, and in that way make people look at life.' This medium also brought a new connection between hand and mind, as if capable of revealing and exploring nascent thoughts before they were formed. In Rego's words, 'I go along with what happens; it's a physical thing.' These qualities made the medium ideally suited to her explorations of taboo subjects, from the 'Abortion' pastels to her 'Life Cycle of the Virgin' series in 2002, recasting the Bible story as a modern tale of teen pregnancy.

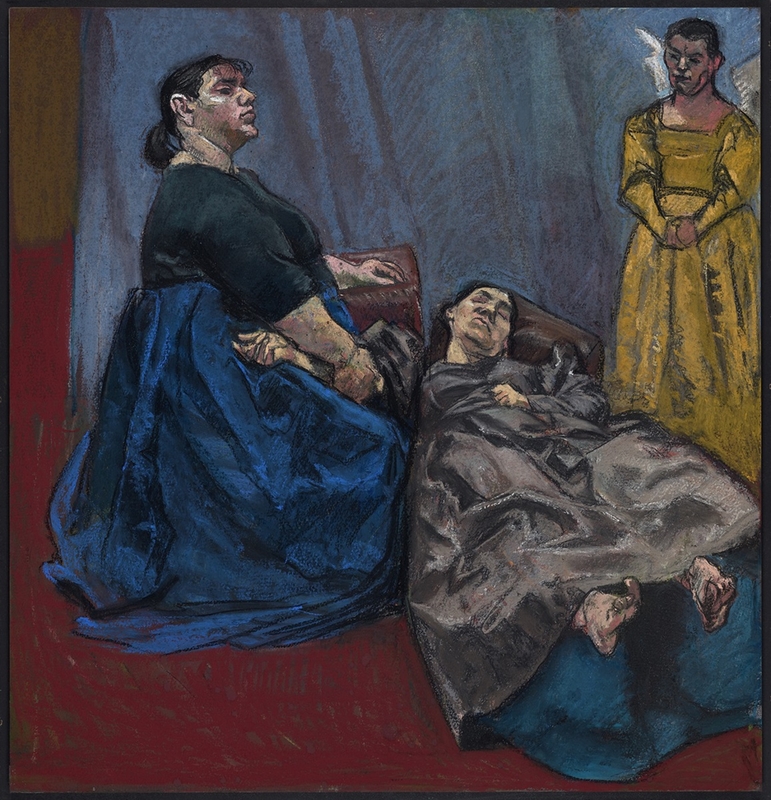

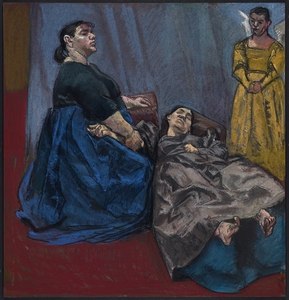

In The Visitation (2002), for example, the Virgin looks out of the scene, her face registering mixed emotions, as the angel delivers the news of her pregnancy. Rego layered pastel colours in a dark, bruised palette of plums and reds, creating an oppressive, bodily and intimate atmosphere. This built-up technique makes the scene tangible, grounding it in the realism of traditional Western figurative painting.

Yet her application also creates a sketchy finish in the upper layers. Strenuous and anguished, then youthful and frenetic, her pastel mark-making communicates the ambivalence of this scene, laying bare the unspoken implications and emotions behind the familiar Bible story. For Rego, 'It always used to be men who painted the life of the Virgin, and now it is a woman. It offers a different point of view, because we identify more easily with her.'

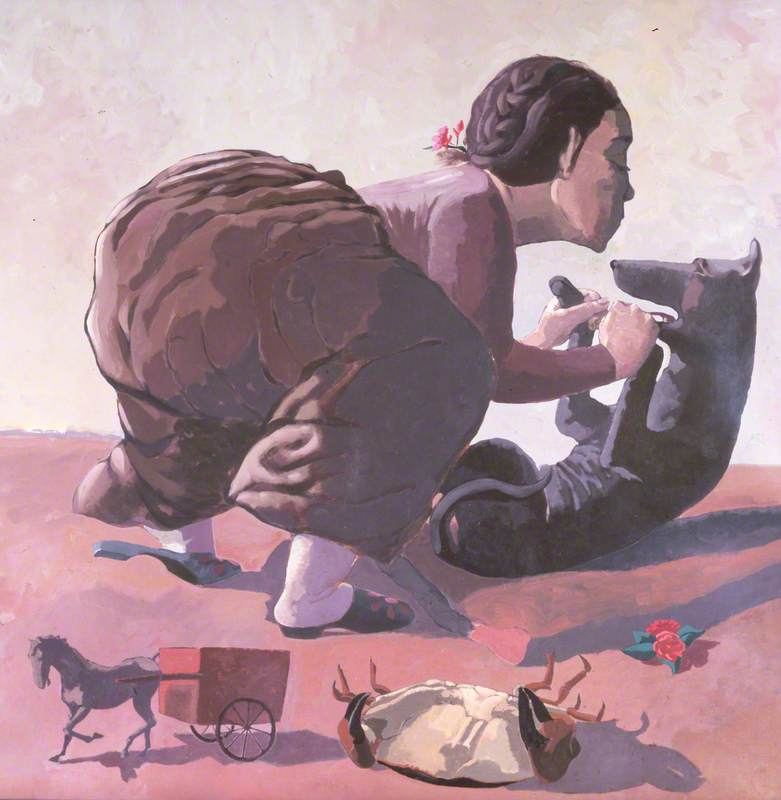

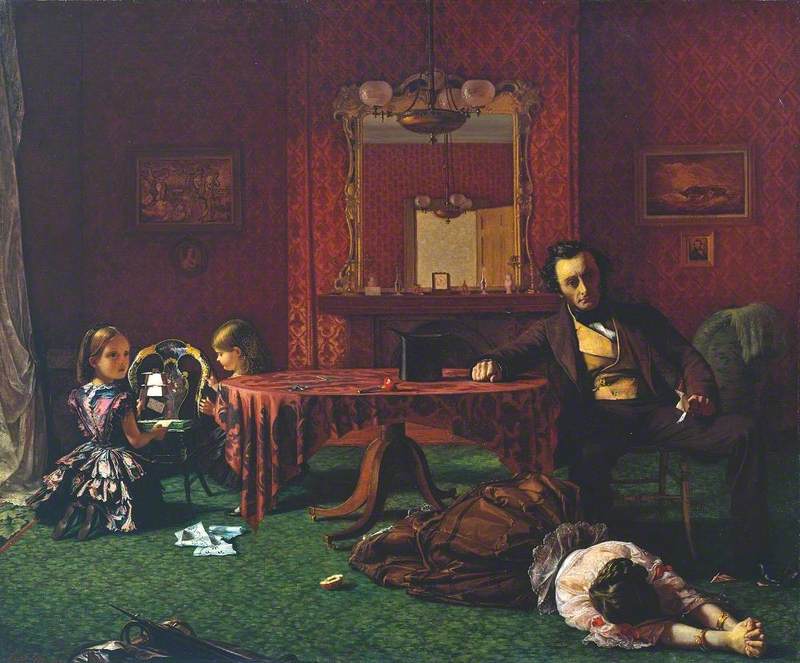

Her violent mark-making lends her pastel works an unsettling dimension – an effect that echoes the often complex and contradictory nature of her subjects. This is perhaps best encapsulated by her works that draw on fairy and folk tales, such as Scarecrow and the Pig (2005), based on a story by Martin McDonagh. In this tale, a pig rescues a scarecrow from a fire. Yet when the farmer comes to kill the pig, the scarecrow does not save him. Rego transmutes the scarecrow into a woman in a green dress, martyred on a cross. Lending the scene a solidity and realness, yet also a crayon-like finish, reminiscent of childhood drawings, pastels enhance the scene's complexity. Worked-up passages create a realism that seems to crack into scrawled lines, as if simmering with anger.

As Rego grew old, this effect became more pronounced. This can be seen, for example, in her pastel drawing from 2014, depicting the Portuguese legend of Inês de Castro, a fourteenth-century noblewoman who had an affair with Prince Pedro of Portugal. After she was murdered by his father, the story goes that when Pedro assumed the throne, he exhumed her body and crowned it in a lavish celebration.

As her practice of layering pastels was particularly demanding, her late works became more loosely drawn, showing the white support beneath, the surface laced with frenetic lines. Violent yet dreamlike, works like Scarecrow and The Pig and Inês de Castro demonstrate how Rego drew out the complex gendered relationships and power dynamics that lurk beneath her subjects. This effect is intensified by her varied application of pastels: sometimes dense and lush, others loose and scrawling. In this way, pastels encapsulate what Rego has called the 'beautiful grotesque'.

While she did not make many portraits, these are especially in dialogue with the legacy of pastels, as portraiture is the genre for which pastels first gained their fame.

Her portrait of the feminist theorist Germain Greer, commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery in 1995, is built up in densely hatched pastels. Presented without surrounding props, the effect is stark and monumental. Bringing realism and rawness to a medium once associated with beautified court figures, the portrait's lack of flattery appealed to Greer: in her own words, 'A portrait that is kind is condescending.' Indeed, it was Rego's unflinching depiction of women's interior lives and roles that brought them together. Greer wrote of her experience with Rego, 'It is not often given to women to recognise themselves in painting, still less to see their private world, their dreams, the inside of their heads, projected on such a scale and so immediately, with such depth and colour…'

In Rego's hands, a medium once mocked as women's art became the tool through which she explored their innermost conflicts and issues, from her 'Abortion Series' to her portraits. Connecting the hand and the mind with new immediacy, pastels allowed for a savagery in her mark-making that shattered the refined origins of the medium. For Rego, 'When you draw you can push your pencil or your pastel – everything is much more violent. Painting is much more lyrical. That's why I took up pastel.'

Alice Blow, writer and researcher

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Fiona Bradley, Judith Collins, Ruth Rosengarten and Victor Willing, Paula Rego: A Retrospective, Tate Publishing, 1997

Ben Eastham and Helen Graham, 'Interview with Paula Rego', The White Review, 2011

José da Silva, ''Don't smudge': Paula Rego gives a unique insight into her work as she is interviewed by leading artists', The Art Newspaper, 2022

Beverley D'Silva, 'Paula Rego: The artist who helped change the world', BBC Culture, 2021

Catherine Lampert and Anthony Spira (eds.), Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, Art Books Publishing, 2019

Maria Manua Lisboa, Essays on Paula Rego: Smile When You Think about Hell, Open Book Publishers, 2019

John McEwen, Paula Rego, Phaidon, 2006

Deryn Rees-Jones, Paula Rego: The Art of Story, Thames & Hudson, 2019