Preparatory drawings have long been used by artists to practise their ideas for paintings, rather like rehearsals before a final performance. These drawings allow the artist to visualise their idea and figure out what to change or adapt for the final composition before they sketch it onto the canvas. Many of these drawings from the nineteenth century survive today, allowing us to see the artistic process in action: by looking at the studies alongside the paintings, we gain an insight into how an idea developed over time.

The young artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood learnt drawing as students at the Royal Academy in the 1840s. Their early exercises involved sketching plaster casts of Greco-Roman sculptures – John Everett Millais' drawing of the sculpture The Pancrastinae was made when he was just 13.

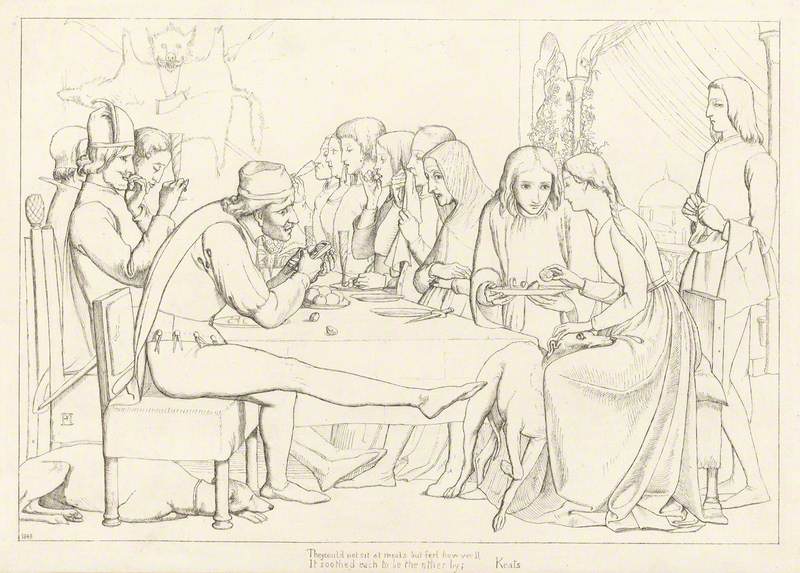

The visual style developed by the Brotherhood after its formation in 1848 was very different. Inspired by early Italian frescoes – or rather, engravings of them which they saw in books – and contemporary German prints by Moritz Retzsch, they practised a drawing technique that emphasised pure outlines, with minimal shading to highlight details. An excellent example is Millais's 1848 drawing inspired by John Keats's poem Isabella: or, The Pot of Basil.

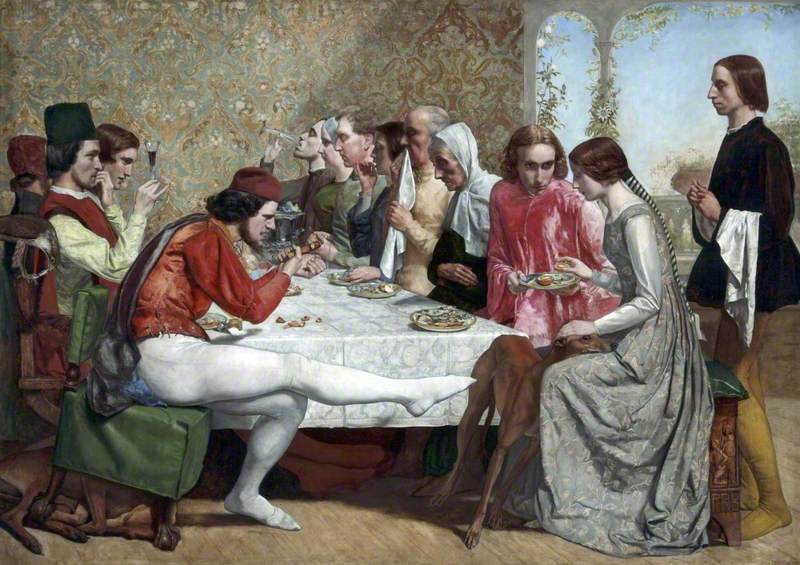

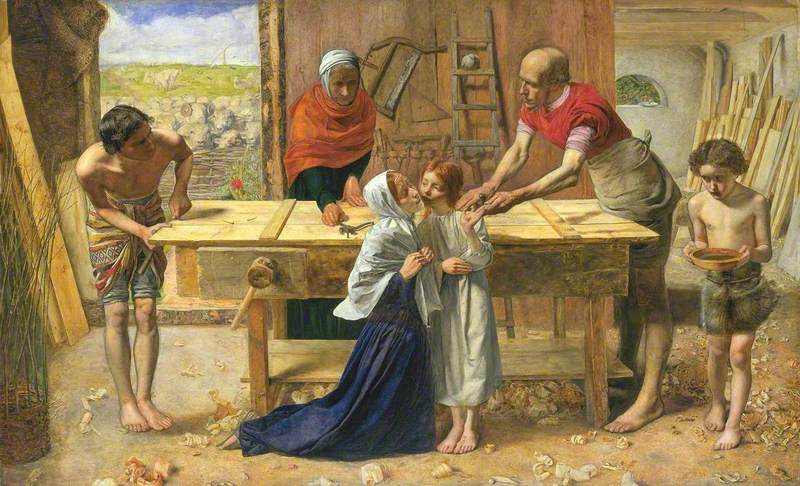

Millais developed the drawing into the painting Isabella, which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849. It depicts a story from Boccaccio's Decameron about the relationship between the aristocratic Isabella and a middle-class clerk, Lorenzo, whose passion for her results in his murder by her haughty, disapproving brothers.

The early study includes a few details which Millais omitted from the painting: outside the window we can see Brunelleschi's dome, indicating the Florentine setting, and the boar skin hanging on the wall alludes to the brothers' hunting pursuits. The drawing also demonstrates that Millais always planned to include the brother's distinctive kicking gesture, cruelly aimed at a greyhound opposite.

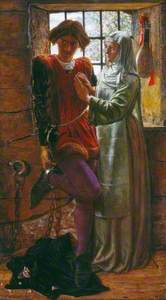

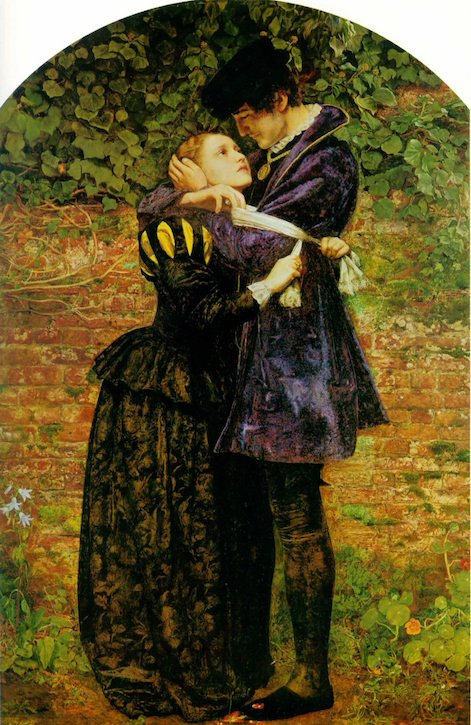

William Holman Hunt also adopted a spiky, medieval style of drawing, but he used copious hatching to achieve a high level of detail. Claudio and Isabella from 1850, adapted from Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, presents a quietly dramatic scene in which the nun Isabella contemplates sacrificing her virginity so that her imprisoned brother Lorenzo can be freed. The drawing differs somewhat from the painting which Hunt eventually exhibited at the Royal Academy.

In the drawing, Isabella clasps her arms around her brother's neck – a stiff, awkward gesture typical of early Pre-Raphaelite works – but for the painting, Hunt had her place her hands more tenderly on his heart.

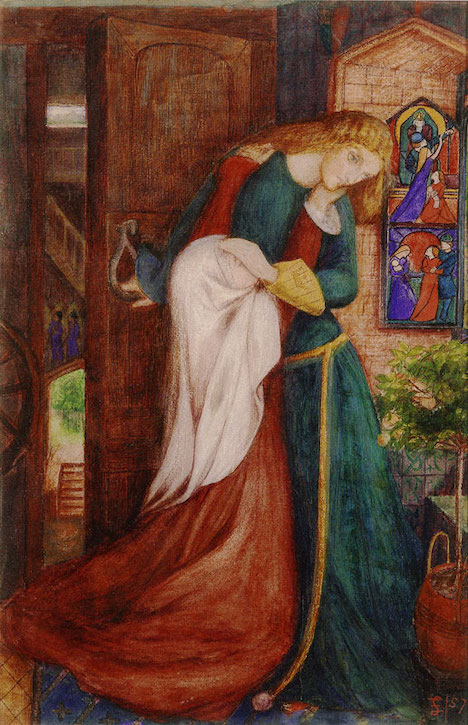

Elizabeth Siddal, who was not an official member of the Brotherhood but was closely associated with it, continued the group's love of making densely worked drawings which also function as independent artworks.

Siddal made this sketch, Lady Clare, as part of a series illustrating poems by Alfred Tennyson, partly at the encouragement of Alfred's wife Emily. Despite the drawing's small size, Siddal crams in many historical details: a portative organ, stained-glass window, tiled floor and swan-filled pond. These indicate Siddal's close study of the medieval illuminated manuscripts she saw in Oxford and London. Eventually, she painted a detailed, jewel-coloured watercolour of the same scene, albeit with several changes.

Lady Clare

c.1854–1857, watercolour on paper by Elizabeth Siddal (1829–1862)

Art historians have labelled the drawing as a 'study for' the watercolour, but Siddal first conceived the former as a book illustration: she only painted the watercolour version later on.

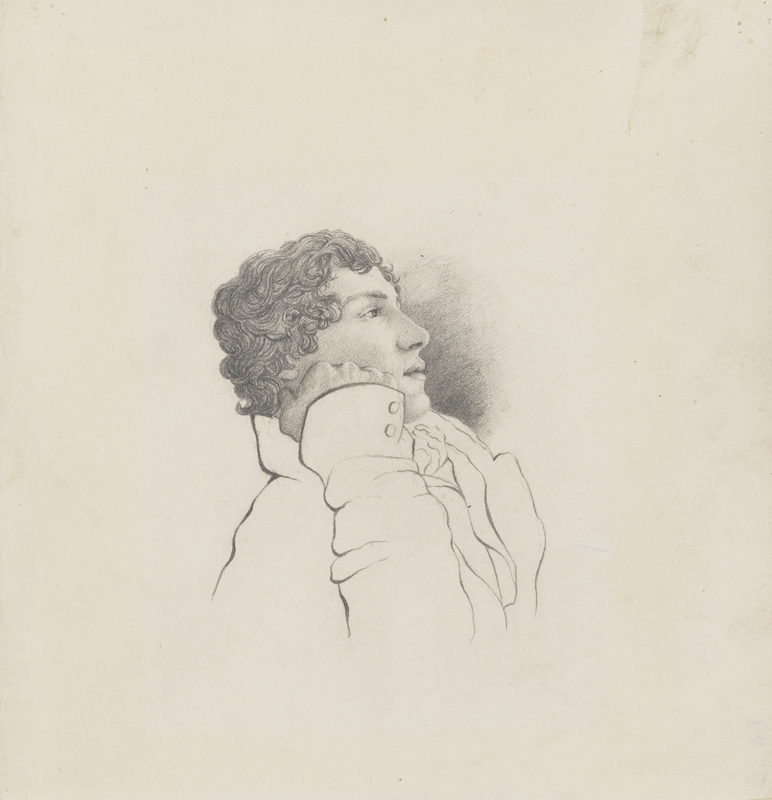

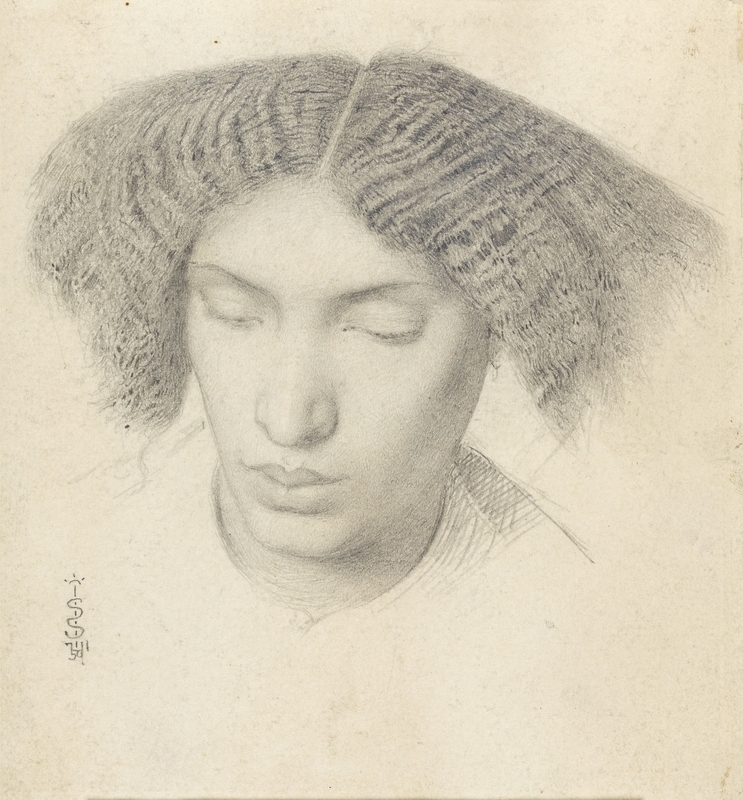

Besides these composition 'rehearsals', the Pre-Raphaelites made observational sketches for specific details within their paintings. One example is Millais's exquisite pencil drawing of a woman's head, made in preparation for A Huguenot, on Saint Bartholomew's Day.

The painting, shown at the RA in 1852, quickly became one of the artist's most popular works because of its poignant subject: a French Catholic woman imploring her Huguenot Protestant lover to wear the white armband which would hide his denomination and therefore save him from the massacre of the Huguenots by Catholics in August 1572.

A Huguenot, on Saint Bartholomew's Day

1852, oil on canvas by John Everett Millais (1829–1896)

The woman's upturned face in Millais's drawing – evidently modelled by Anne Ryan, a professional model – is slightly different from the painted version, but the former clearly demonstrates the artist's commitment to capturing natural details: the light reflecting off Ryan's glossy hair and the shadows under her eyebrows. Such drawings also remind us of models' actor-like participation in the artistic process: Ryan had to adopt a specific facial expression so that Millais could replicate the emotions in the scene.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, another member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, delighted in making preparatory drawings when creating his well-known images of 'beautiful women with floral adjuncts', as his brother William Michael described them. Rossetti's drawings of Siddal from the 1850s already show his obsession with physical beauty, although they are simply tender observations of Siddal herself rather than studies for narrative or historical pictures.

In the early 1860s, Rossetti began to create more sumptuous images of women.

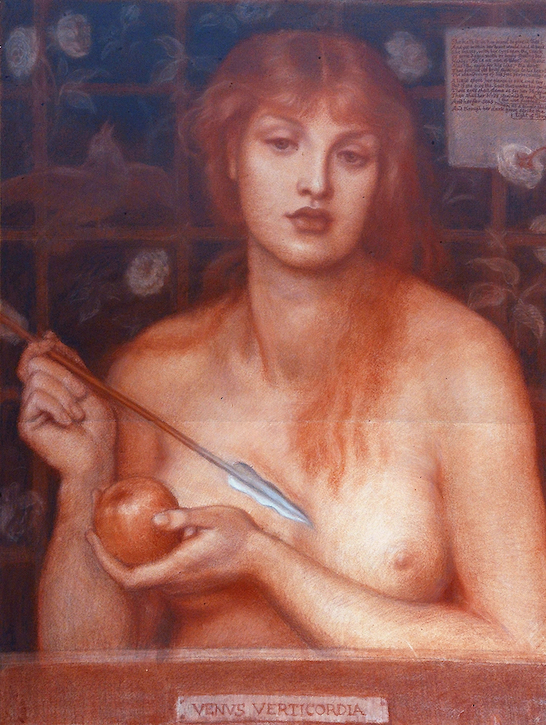

Study for 'Venus Verticordia'

c.1863–c.1864

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

This pencil drawing depicts a woman posing as a Venus-like figure who, in Rossetti's words, 'turns men's hearts' (presumably towards desire rather than chastity). It is principally a figure study, although it already includes the symbolic arrow and apple which appear in the painting Venus Verticordia.

However, besides the painting, Rossetti executed two complete drawings in coloured chalks for his patrons William Graham (in 1863) and Frederick Leyland (in 1867), which are almost as large as the oil version.

Venus Verticordia

1863, coloured chalks on paper by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

Despite the 1863 drawing being a completed work, the art historian Virginia Surtees catalogued it as a study for the oil, reinforcing a traditional view in art history that drawing is ultimately subordinate to painting. In reality, Rossetti treated the chalk version as an artwork in itself, even inscribing a sonnet in the upper-right corner which is not present in the painted copy.

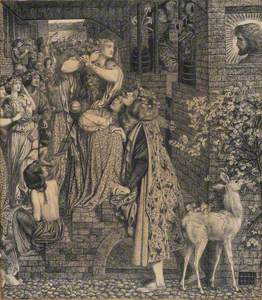

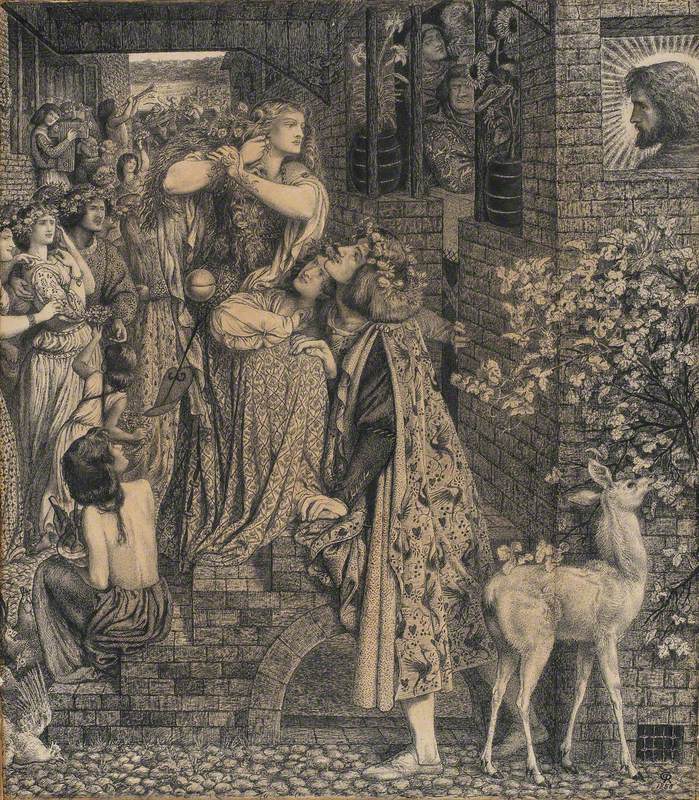

Today, Pre-Raphaelite preparatory studies are valued as standalone artworks in their own right. We have already seen the highly finished drawings by Millais, Hunt and Siddal, which are as detailed and immaculate as the paintings and can be enjoyed equally. In many cases, the artists did not intend these drawings to be seen by a wider audience – it was their paintings that appeared in public exhibitions. Yet some Pre-Raphaelite pictures exist only as drawings, like Rossetti's Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee.

Mary Magdalene at the Door of Simon the Pharisee

1858

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

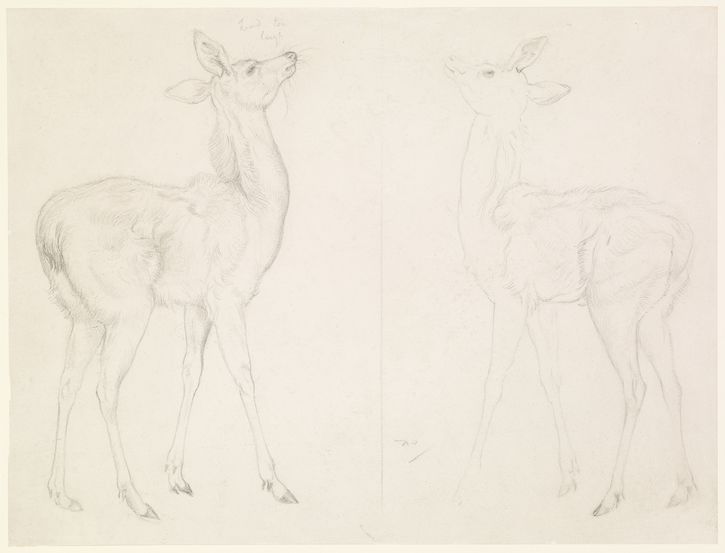

Rossetti contemplated painting this subject, but only ever produced this elaborate pen and ink drawing, which he sold to Thomas Plint in 1860. In a curious inversion of the hierarchy of media, Rossetti made preparatory studies for the finished drawing, like these delicate sketches of a fawn.

Two Studies of a Fawn

c.1858, pencil on paper by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

The different materials used in these drawings tell us something about the Pre-Raphaelites' changing styles. The early Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood works are often executed in pen and black ink to emphasise crisp, severe outlines, while Rossetti's 'Aesthetic' preparatory studies often use softer, silkier pencil, crayon and coloured chalk. We can compare, for instance, Millais's spiky pen-and-ink illustration of a scene from Romeo and Juliet from 1848 with Rossetti's La Donna della Fiamma of 1870, made in a combination of pastel and pencil.

The Death of Romeo and Juliet

1848, pen & black ink by John Everett Millais (1829–1896)

The material choices complement the pictorial theories of Pre-Raphaelitism: pen and ink were ideal for the Brotherhood's creed of 'truth to nature', which called for high levels of detail, while the softer chalks and pencils of Rossetti were more apt for the later Aesthetic movement, which emphasised poetic feeling over clearly delineated fact. La Donna della Fiamma is an exercise in pure mood, while Millais's tightly packed composition communicates a clear narrative. In this way, works on paper are just as effective for understanding the volatile changes in Pre-Raphaelite art as the large oil paintings more often seen on museum walls.

Robert Wilkes, art historian

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Colin Cruise, Pre-Raphaelite Drawing, Thames & Hudson, 2012

Jan Marsh, Elizabeth Siddal, 1829–1862: Pre-Raphaelite Artist, The Ruskin Gallery, 1991

Jason Rosenfeld and Alison Smith, Millais, Tate Publishing, 2007

Virginia Surtees, The Paintings and Drawings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: A Catalogue Raisonné, Clarendon Press, 1972