Belonging to a famous family can be something of a double-edged sword. It has obvious advantages: expertise, networking, inherent talent. At the same time, however, it can command extremely high standards from within the family circle, and an expectant public. How does an aspiring artist balance this burden of expectation with the desire to carve out his or her own niche?

One young woman who faced – and surmounted – such a challenge was the artist Orovida Camille Pissarro (1893–1968).

Winter (The Skaters)

1936–1938, egg tempera on linen by Orovida Camille Pissarro (1893–1968)

Orovida was born in Epping, Essex, in 1893, the only child of Lucien and Esther Pissarro. Her father, Lucien Pissarro (1863–1944), was an acclaimed artist and graphic illustrator, while Lucien's father, Orovida's grandfather, was the eminent Danish-French painter Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), a founding father of the Impressionist movement.

From as young as five years old, Orovida appeared to show artistic potential. Upon receiving one of her drawings, her grandfather wrote to Lucien that she showed 'skill in drawing, it was written that she would. Her drawings are already full of sentiment, elegance, waywardness.'

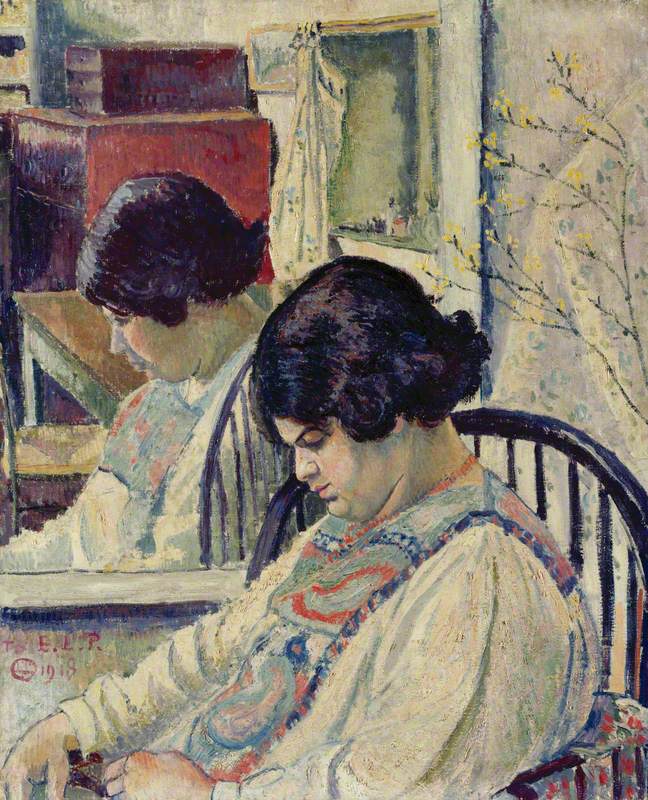

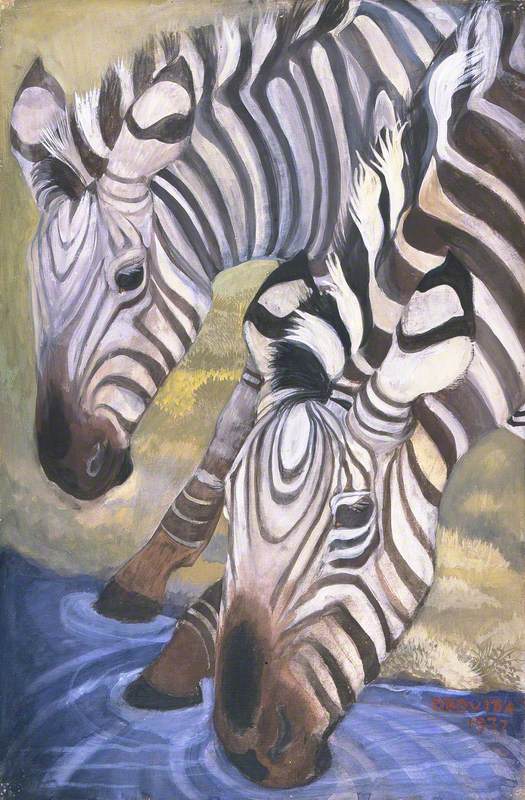

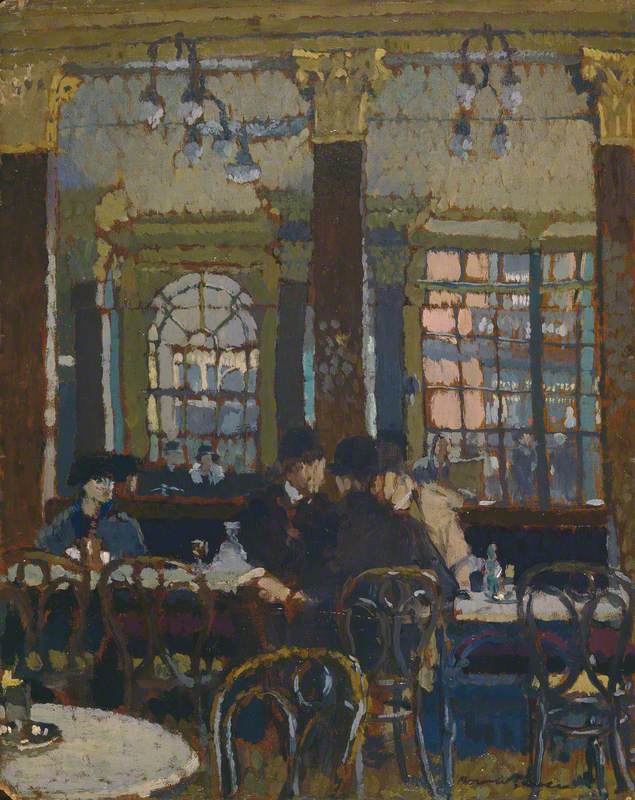

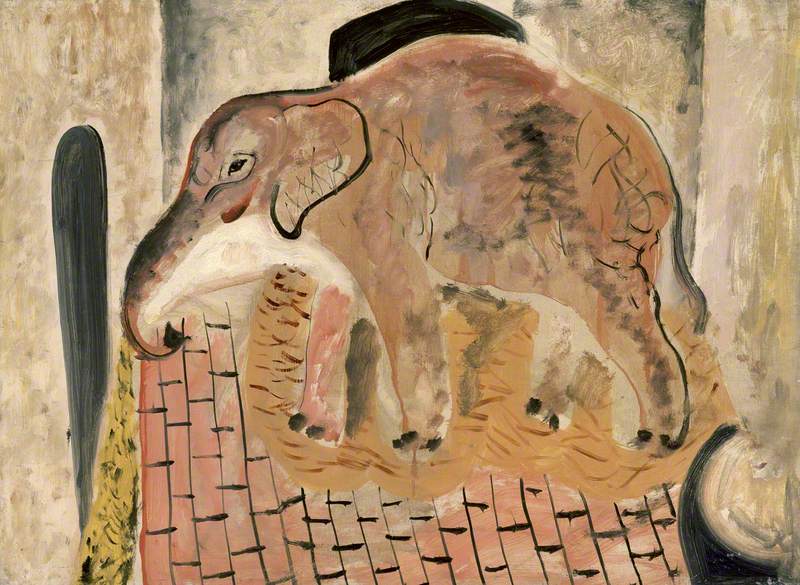

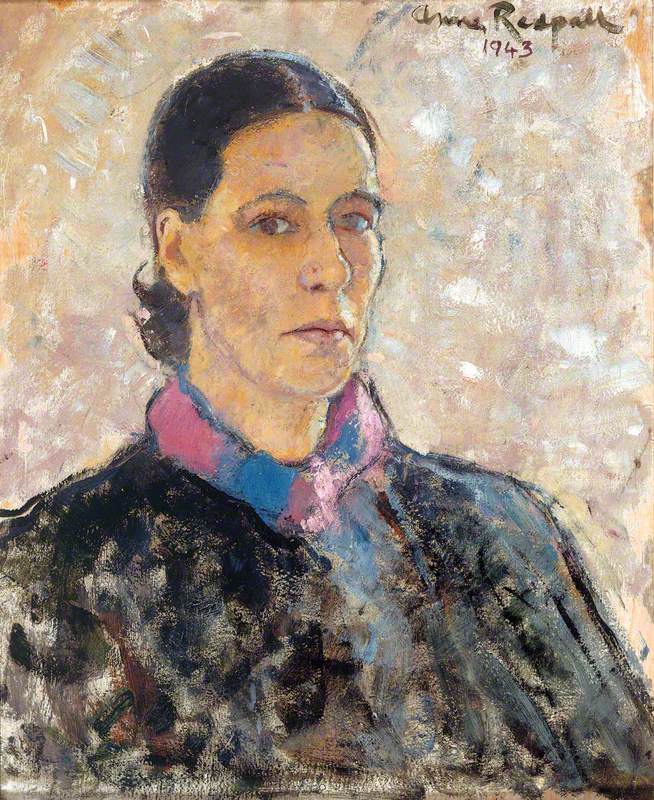

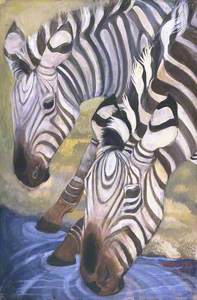

Orovida initially learned the rudiments of Impressionist painting from her father, producing her first self-portrait in 1913. She began a short-lived spell of studying life drawing under Walter Sickert, co-founder (with Lucien) of the post-Impressionist Camden Town Group, but she soon abandoned formal art studies altogether after taking exception to Sickert's didactic teaching style. One thing she did enjoy, however, was frequent visits to London Zoo to study and draw the animals.

Much to her father's dismay, she turned her back on Impressionism – and dropped her famous surname, choosing simply to be known as 'Orovida'. This was done not as a rejection of her family, to whom she remained close, but in a bid to make her own way, on her own terms: a bold move for a young woman. The wayward streak first detected by her grandfather was becoming ever more apparent.

On the cusp of the Roaring Twenties, Orovida was a product of her time, a free spirit. The first female in the Pissarro family to become a professional artist, she broke ranks with her father, grandfather and four artist uncles, and refused to rely on her family's name and reputation.

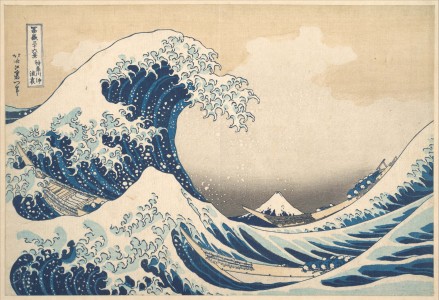

At the same time, she was also breaking free from what she felt were the confines of Western art, instead looking east for inspiration. In a letter to her father in 1922, she wrote: 'Western art has led us straight to the photo and Eastern art is still free.'

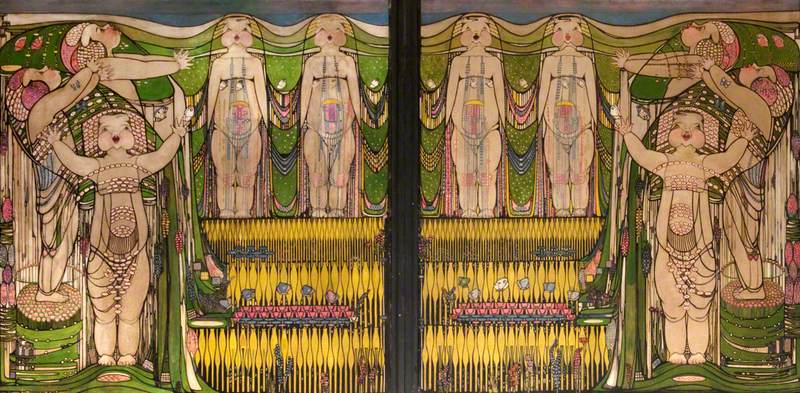

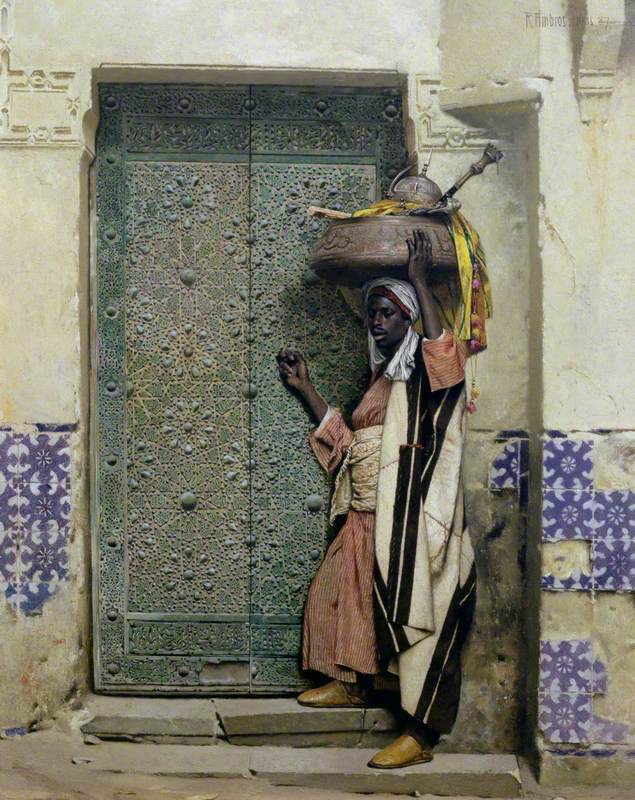

Embracing Orientalism and Exoticism – aesthetic trends that came to prominence in the nineteenth century – she was influenced by her uncle Georges Manzana Pissarro's decorative techniques. Yet Orovida created her own unique style, weaving together strands of Chinese, Japanese, Indian and Persian art, which resulted in stylised, dynamic compositions.

Her vivid imagination prompted her to create images of her beloved animals, etched deep in the memory from zoo visits, but reimagined in more flamboyant surroundings, effectively taking them out of their cages and back into the wild.

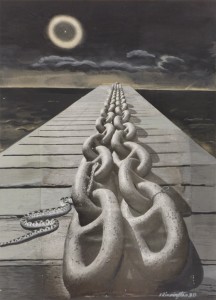

Orovida's non-conformist approach extended beyond subject matter to experimenting with different media and techniques. Starting with oils, she moved to egg tempera and gouache, mainly mixing and preparing her own paints. She was also a prolific printmaker and engraver, who would go on to produce around 8,000 impressions from more than 100 etched plates. An early example of her etching style can be seen in Tiger and Python (1917).

Tiger and Python

1917, etching by Orovida Camille Pissarro (1893–1968)

A review of her 1919 exhibition, 'Etchings and Drawings by Orovida' in The Athenaeum declared: 'Orovida is a painter of animals, a statement which conjures up memories of Landseer, Swan and other exponents of the realism of the Zoo. But Orovida is better than this, for she has realised that primarily an animal is an instrument of pursuit or of escape – that upon its speed depends whether it dines or is dined upon.'

'And she has designed her small pictures to express this dynamical necessity. This shows especially in her first-state etchings, in which she uses the rapid flow of the etching needle to its best advantage.'

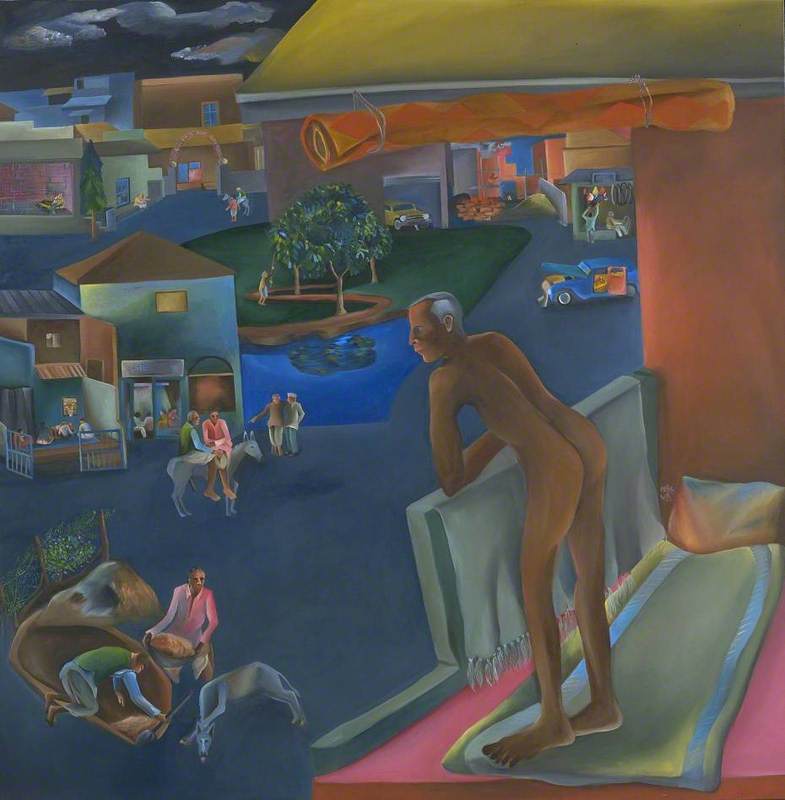

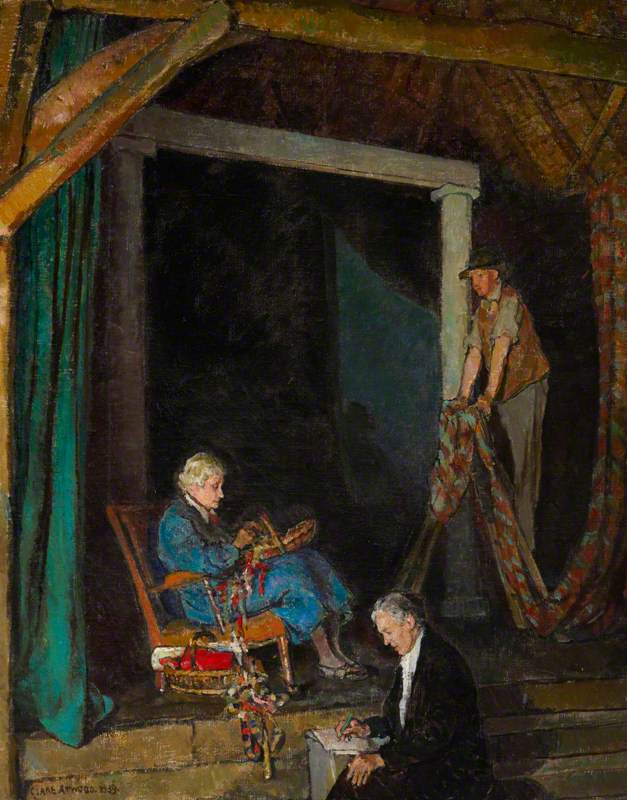

Orovida produced some of her most elaborate work during the 1930s, including decorative tempera panels The Archer's Return (1931) and The Tiger Hunt (1932) – but, surprisingly, she changed media in the 1940s, reverting to painting in oils. She stopped using egg tempera completely, but this is believed to have been out of necessity due to food rationing during the Second World War.

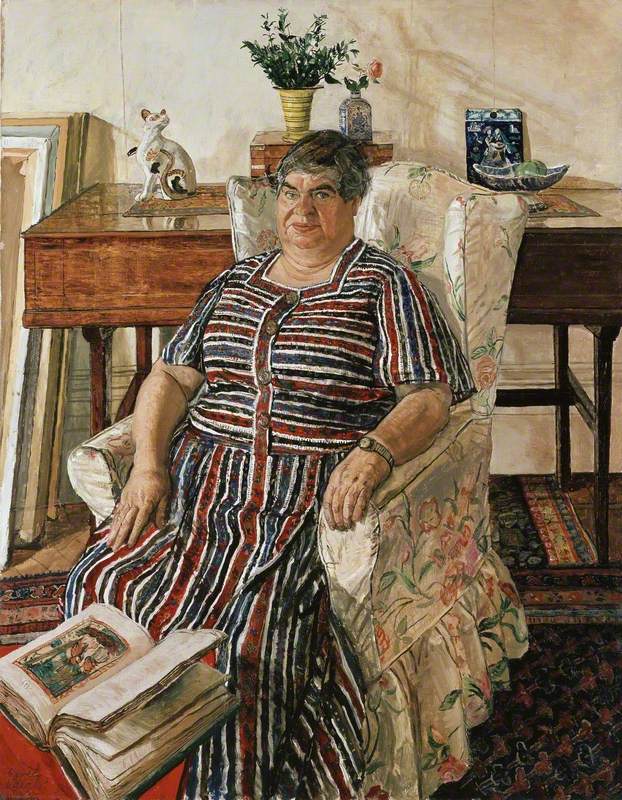

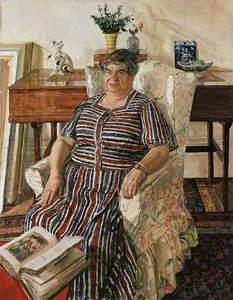

More remarkably, she also changed her style around the same time, adopting a traditional focus. Free-flowing, exotic compositions, once the hallmark of her work, were largely replaced by muted, domestic settings, depicted in paintings such as Family Supper (1938) and Winter (1940).

Her return to oil painting included Self-portrait (1953), again a conventional, formal pose, very much in the vein of her first endeavour 40 years previously. However, her abiding love of cats big and small did not wane, as demonstrated in Tiger Surprises Black Bucks (1960) and Cats (1964).

Orovida continued to paint until her death in 1968. Although her paintings and prints can be found in a number of public collections in the UK, USA and Australia, there has been a distinct lack of scholarship on her work, and few exhibitions, since her death. Despite Orovida's family connections, she was still, essentially, an unmarried woman artist who, like a great many of her contemporaries, likely struggled for recognition during her lifetime.

More of her works can be viewed in Stern Pissarro Gallery's online illustrated catalogue.

Kay Carson, writer