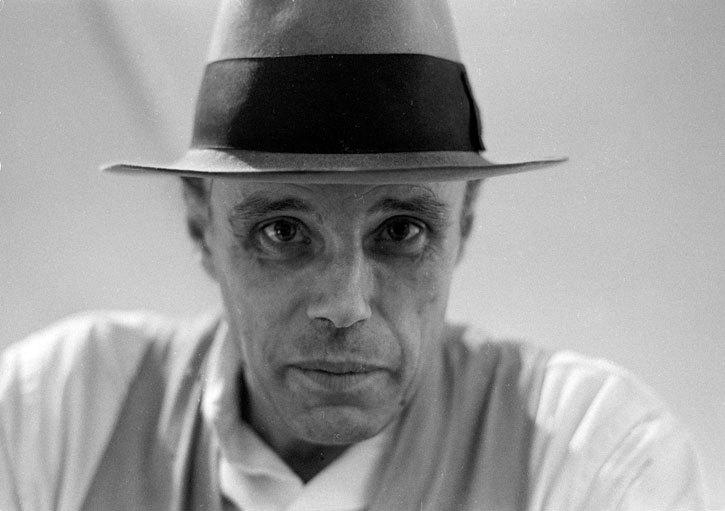

In his regular uniform of fedora hat, felt suit and fishing vest, Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) was one of the most recognisable artists of the twentieth century.

As we mark the centenary of his birth, Beuys continues to be regarded as one of the most influential post-war artists – not only because of his provocative works, merging art and life, but also for expanding the concept of art more broadly. He is often credited with contributing to the formation of the Fluxus movement in the 1960s, as well as 'social sculpture', both of which continue to inspire younger generations of artists today.

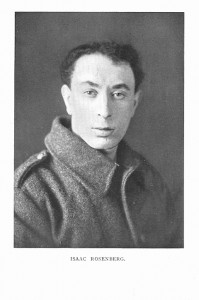

Joseph Beuys

1969, photograph by Klaus Eschen

By often describing his works as 'actions', the German artist directly inserted himself into his artworks. One of the most famous examples is perhaps I Like America and America Likes Me (1974), a durational work created by spending three days locked in a New York gallery with a coyote.

Beyond his innovative artistic work, Beuys' philosophical ideas embraced academia, especially through the Free International University which he helped devise in the 1970s. From the late 1960s, he turned towards politics, co-founding his home country's Green Party (Grünen) in 1973 and later designing the party's poster.

Beuys' utopian beliefs can be understood partly through his complex biography (he served as a Luftwaffe pilot during the Second World War and was interned in a British prisoner-of-war camp). He spent nearly a decade recovering from the psychological turmoil of the war, during which time he became introspective, coming to terms with his involvement in the conflict. His interests in social and ecological issues led him to the spiritual teachings of the Austrian social reformer and philosopher Rudolph Steiner.

A useful starting point for understanding Beuys is the artist's publication, What is Art? The book is based on a series of conversations between Beuys and his friend Volker Harlan, and was published by the latter in German in 1986, and translated into English 18 years later. Here, Beuys discusses concepts he created, such as 'social sculpture', alongside other ideas that permeated his career, including his famous mantra that 'everyone is an artist'.

Here are nine key artistic concepts defined by Beuys in What is Art?

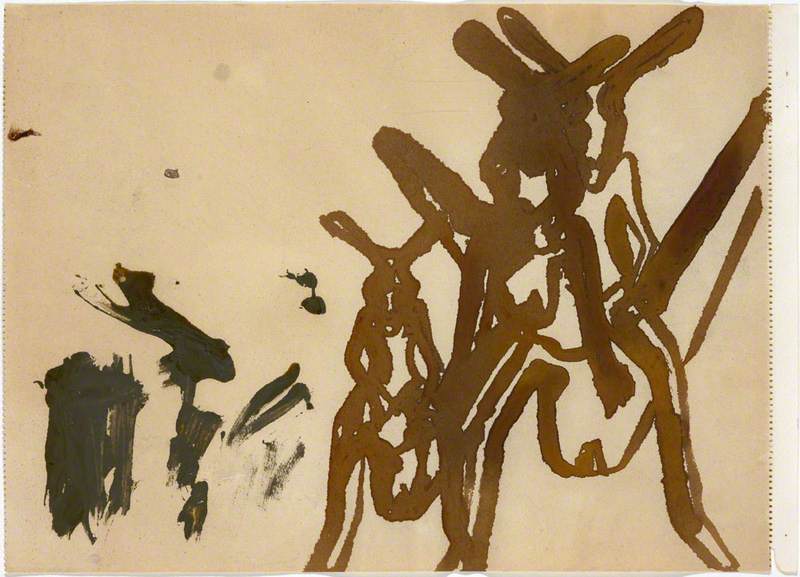

1. Thinking = Sculpture

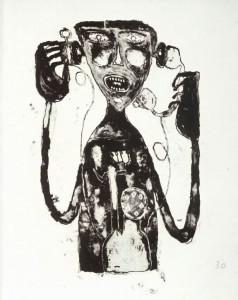

Creation begins with thought. This idea may seem axiomatic, but for Beuys, this meant an artwork encompassed so much more than a finished piece: its genesis and generation were essential parts of its nature, hence why he saw his actions as artworks in their own right. Likewise, speaking = sculpture. Beuys believed 'even when I write my name, I am drawing.'

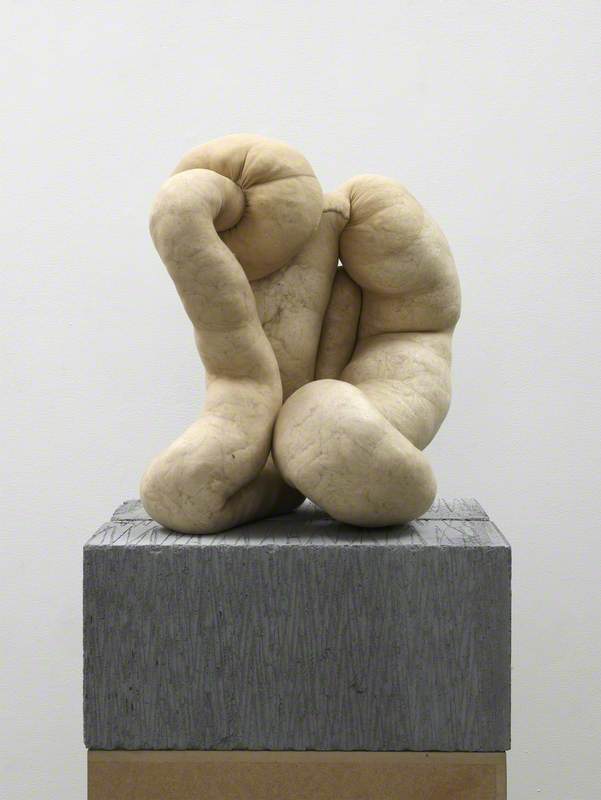

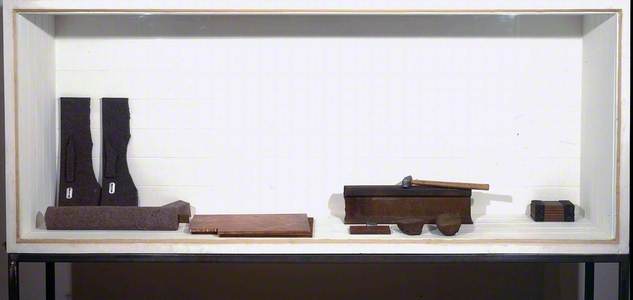

Yet Beuys had strong views on more traditional forms of sculpture, which he saw as moving materials between two opposed poles: undetermined chaos (say a blob of melted fat), and determined order (a cardboard box).

'I realised that [sculpture] is composed of forces, that it has very important components. And only when you are really aware of the components, can you then judge or determine where to position a sculpture.'

2. Parallel process

At the art shows 'Documenta 5' and 'Documenta 6' held in Kassel, Germany (1972–1977), Beuys' contributions were in the form of marathon public discussions (up to 10 hours a day for over 100 days). For the artist, such debates, lectures and conversations were as important as his object or action-based work, a concept he described as 'parallel process'.

Beuys stated: 'My objects are to be seen as stimulants for the transformation of the idea of sculpture... They should provoke thoughts about what sculpture can be and how the concept of sculpting can be extended to the invisible materials used by everyone.'

3. Social sculpture

For 'Documenta 6', Beuys' Honey Pump in the Workplace (1977), brought together thousands of individuals and groups from across the globe to discuss how to live cultural and spiritual lives. This was an artwork in its own right, for if thought was sculpture, then people thinking together was, in Beuys' terms, social sculpture.

joseph beuys : honey pump at the workplace pic.twitter.com/WODRcWKGnV

— |||||| (@rndmndx) June 17, 2019

'I want to get things to the stage where people experience themselves as being continually involved in this question [of form],' he said. 'And then, as they keep experiencing and creating these material processes, that they basically also experience that social sculpture is a necessity.'

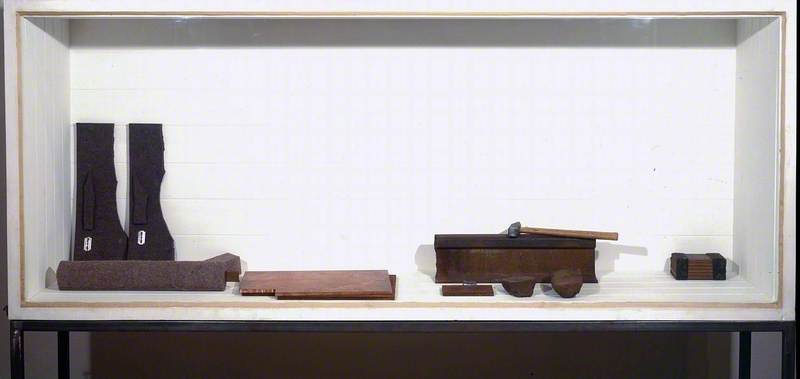

4. Art is its materials

Despite the conceptual bent of much of his creativity, Beuys took great care in choosing raw materials to work with, focusing particularly on substances from the natural world that inherently contained more meaning than mere, say, pigment. His intention was that 'art does not remain something merely retinal.'

By using wax, felt or fat, Beuys sought to link 'the whole nature of substance... to painting for example, or to sculpture or drawing: so that one has to enter into the forces in these substances.' These materials could then act as symbols, pointers, or tools, referencing, for example, their medicinal properties.

This places an onus on the artist to respect the materials. Whatever you create 'has to be brought into a form in which the material and the forms are really in accord with each other, and are satisfied and want to keep on living.'

5. Art is eternal

To be successful, art has to adhere to long-lasting values rather than short-term trends. In conversation with Harlan at a church in Bochum, Beuys regularly referred to objects around him: the flooring, brick walls, chairs and table.

The quality of the latter, for example, depended on its proportions: dimensions, rhythm and scale. 'There needs to be a certain timelessness in its rightness... The table must have an eternal value, it must have an intrinsic need to want to keep living.'

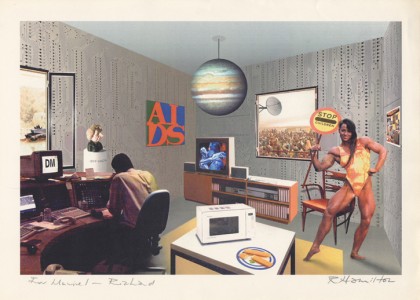

6. Art is value

With Beuys' definition of art as encompassing all of our activities, the artist insisted it could replace capitalism as a measure of our worth and productivity. Beuys was against twentieth-century consumerism but did not see Marxist ideologies as the answer.

'The concept of art must replace the degenerate concept of capital,' he said. 'Art is really tangible capital... Money and capital cannot be an economic value, capital is human dignity and creativity. We need to develop a concept of money that allows creativity, or art, so to speak, to be capital.'

7. Art is communication

How do you know when a work is finished? For Beuys, the answer involved separating himself from his original intention and thinking about what it needed to achieve completion. He often did this by thinking about the needs of the raw materials involved.

'I never say: I declare this thing finished; but rather I wait until the object itself lets me know and says: I am finished.'

Likewise, the success of a work is founded on its ability to communicate. 'You've made the greatest efforts, and then you suddenly see – what do you see? – yes, people describe this by saying: it just doesn't speak.'

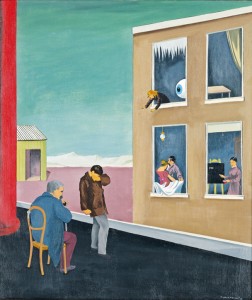

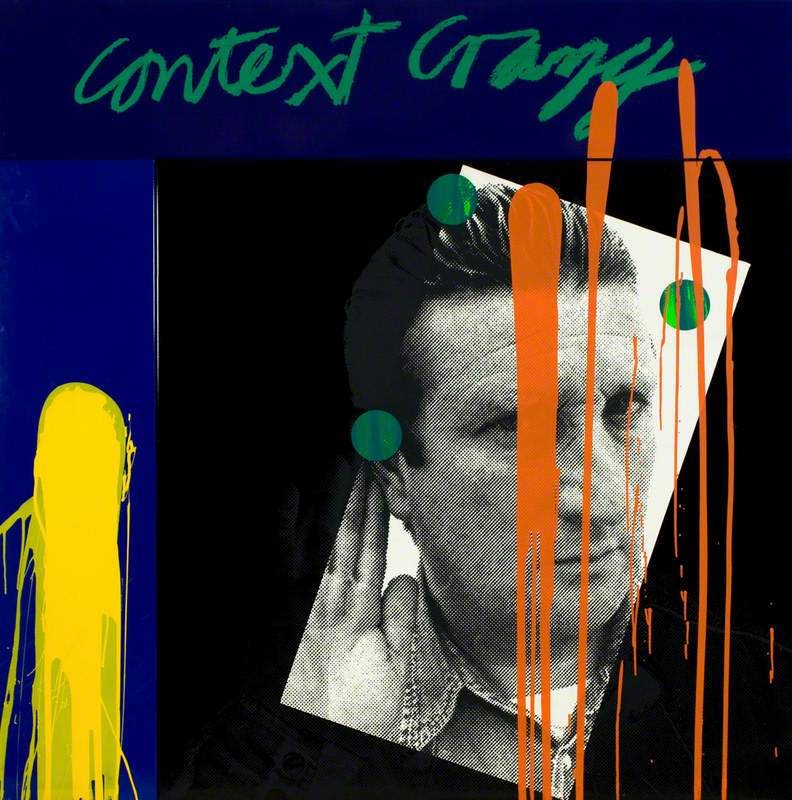

8. Art fits into context

Beuys delineates objects around him into those that are 'alive' or 'dead' (though ironically it is the latter, for example, items that are thoughtlessly or garishly designed) that tend to force themselves into our minds.

For Beuys, great art 'just doesn't force itself on you at all, but rather completely merges with its context, [it] almost vanishes in nature.'

He took as an example a perfectly proportioned Greek temple next to a gnarled olive tree – each object, in Beuys terms, believing the other was the more beautiful. 'They are one and the same thing; things interpenetrate each other. There is really a unity there, which is not present in such... run-of-the-mill consumerism.'

9. Every human being is an artist

Ultimately, Beuys sought to inspire creativity in everyone he met. He believed we all share the capacity to shape our lives and the world around us, in the manner of an artist creating a work. Life itself should be an artwork.

This idea – that everyone is an artist – was partly inspired by Beuys' studies of the eighteenth-century German poet, Novalis. Allowing people the space to merge art and life this was at the heart of his career, he explained: 'First of all, we have art as the science of freedom,' and the essence of being human was 'the expression of freedom, embodying, carrying forward and further evolving the world's evolutionary impulse.'

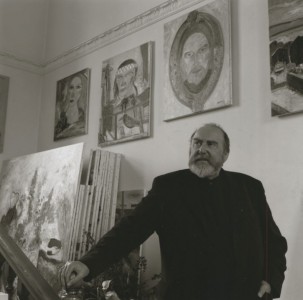

Joseph Beuys

1975, photograph by Caroline Tisdall

To see these ideas in practice, we only need to look at how the 100 years since Beuys' birth are being commemorated by events around the world.

Amongst them is 'Beuys' Acorns', the planting of 100 oak saplings outside Tate Modern, London. This work by Culture Declares Emergency co-founders Ackroyd & Harvey is inspired by Beuys' own 7000 Oak Trees (1982); indeed, these young trees have been grown from acorns the pair collected from specimens the German artist and his helpers planted in Kassel, Germany.

Joseph Beuys planting one of his 7000 Oak Trees in Kassel pic.twitter.com/fpgSWDeF99

— The Imaginative Press (@Imag_Press) October 15, 2019

Looking at how Beuys defined art, one only can only imagine that he would have approved of how artists are responding to the climate crisis today.

Chris Mugan, freelance journalist

The programme 'Beuys 2021. 100 years of Joseph Beuys' organised by the Ministry of Culture and Science of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia in collaboration with the Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf runs for the duration of 2021 across Germany.