In the first years of the twentieth century, in an age of political upheaval and frantic artistic invention, Natalia Goncharova (1881–1962) was exceptional in her appetites and versatility. At various times, she was a Primitivist, a Futurist, a Cubist, a Rayonist, an Orientalist, as well as a leading theatre and costume designer. Her influences were correspondingly wide-ranging, taking in the high Modernism of western Europe and the folk art of her native Russia. The term 'Everythingism' was coined to label her diverse and voracious approach.

Image credit: The State Tretyakov Gallery

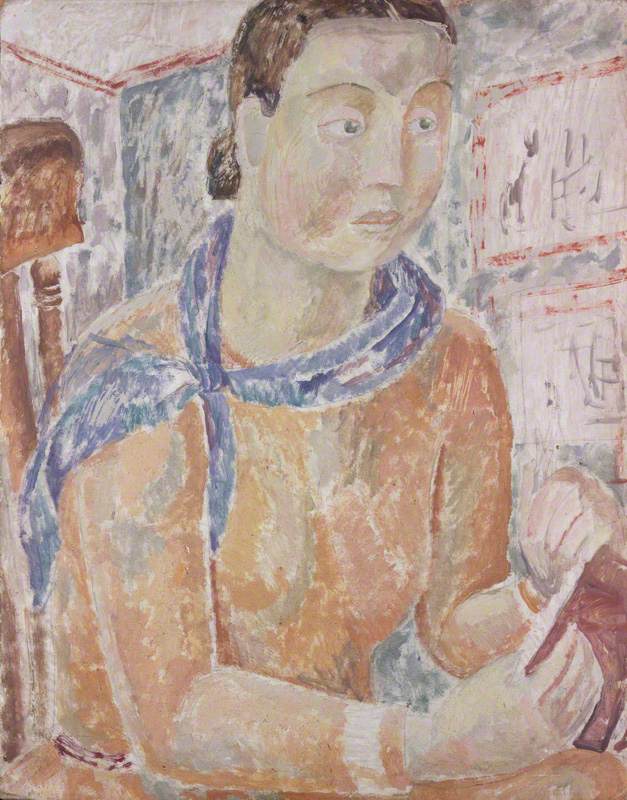

Natalia Goncharova at her studio

mid-1920s–1930s, photograph by an unknown artist. Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery

The diversity of Goncharova's work reflects a complex set of influences. The avant-garde encouraged eclecticism, for sure, but Goncharova responded to particular – and sometimes conflicting – circumstances. She was of aristocratic stock yet grew up in relative poverty on the family estate; she was Russian but settled in Paris, having rejected, at least in her rhetoric, the art of the West. She had a powerful attraction for the traditional ways of the countryside, yet was keen to capture the emerging industrial age in her art. And she was a woman in a world of male artists.

Image credit: larionov.tretyakov.ru (source: Wikimedia Commons)

An exhibition in Moscow

Left to right: Mikhail Larionov, Sergei Romanovich, Mikhail Le Dantiu, Natalia Goncharova, Maurice Fabbri and Vladimir Obolensky

The variety of her artistic styles can seem a mishmash with no clear developmental journey. As Jane Ashton Sharp writes: 'Looking at individual paintings, we frequently cannot fix the moment at which we have entered her oeuvre. Rather, we are forced to acknowledge her repetitiousness, her mastery of diverse media, styles, and traditions…'. This is made more challenging by Goncharova's deliberate habit of not signing and dating her works, which is indicative of her lack of interest in a clear sense of linear development.

The year 1913 saw Goncharova's major one-woman exhibition in Moscow, the first monographic exhibition of any modernist artist. In the same year, she published a manifesto that forcefully rejected western art, whilst thanking it for what it had given her. 'The West', she wrote, 'has shown me one thing: everything it has is from the East'. Impressionism has its roots in Japanese art, she writes, Cubism uses African art, Matisse takes from China. Her rejection of the West was, therefore, an attempt to put Western art in its place – to remind it that it was not the wellspring of innovation, and perhaps to chasten it into acknowledging its sources. She would look to the East for inspiration, through its folk art, religious icons, and the art of popular prints.

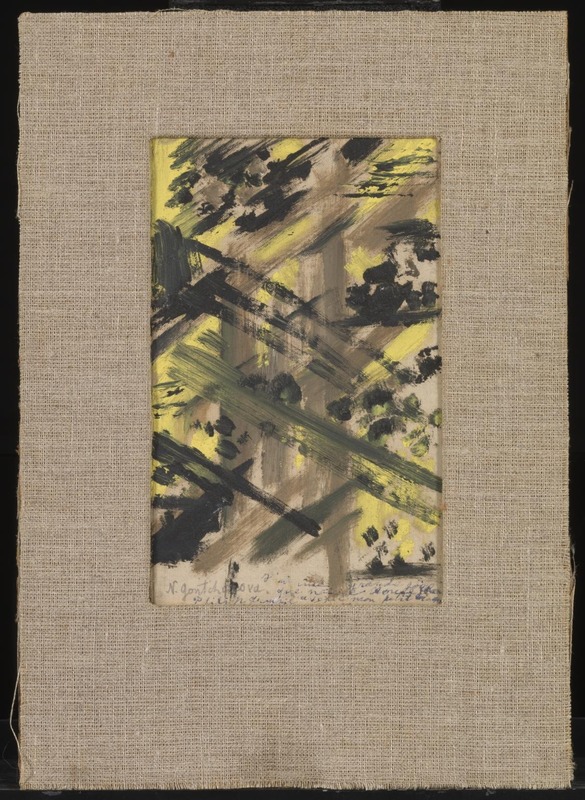

One outcome of this urge to free herself from Western influence was Rayonism, a style she developed with her lifelong partner, the artist Mikhail Larionov. This style, which aims to capture the essence of things through the light they reflect was, she claimed, 'free from concrete forms, existing and developing according to painterly laws!' Goncharova had found degrees of abstraction earlier in her career, as represented by two complementary paintings in Tate Modern: Country by Day (c.1911) and City by Night (c.1908).

Although Larionov's Rayonist works achieved a high level of abstraction, such as Nocturne (c.1913–1914), Goncharova combined its effects with a Futurist idiom, satisfying her concern for machines and movement.

Goncharova's attraction to folk art's vibrant colours and expressive qualities may stem from her childhood spent on the family estate. At a time when industrialisation was replacing traditional crafts and agriculture, we detect in Goncharova's work a celebration of the old ways and a suspicion, to say the least, of the new. But she cannot deny her interest in the machine age, as expressed by the Italian Futurists. In a manifesto of 1913, she and Larionov wrote: 'We exclaim: the whole brilliant style of modern times – our trousers, jackets, shoes, trolleys, cars, airplanes, railways, grandiose steamships – is fascinating, is a great epoch, one that has known no equal in the entire history of the world'.

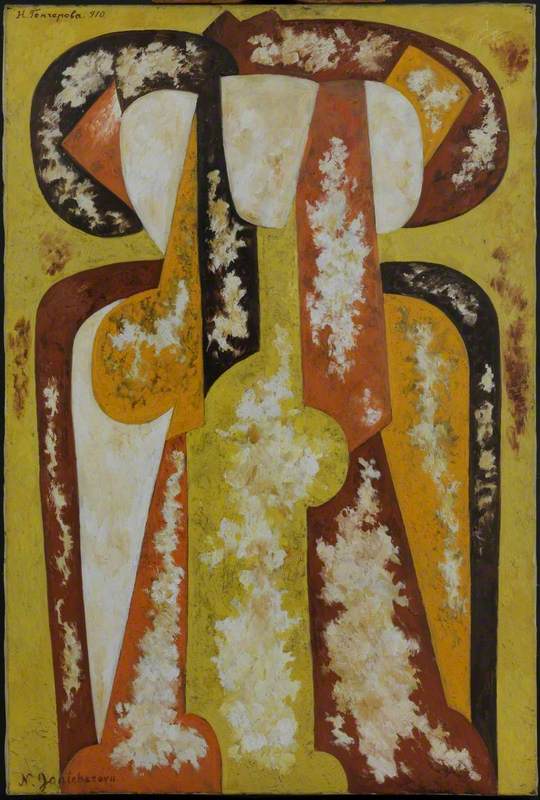

The figure of The Weaver (1910), rendered in Rayonist forms, transparent and incomplete, has to be looked for against the imposing presence of machinery. To all appearances, her lower body is being drawn into the machine, under the lower roller, like a skein of fabric to be gobbled up. Her face is all timeless concentration as it contends with this monstrous new machine. It is a claustrophobic cell in which the monster makes its demands, lit by a surveilling light.

At first sight, Gardening (1908) seems to be a celebration of agrarian life, but it is a strange representation of its subject. We see two women on a patch of grey earth with potted tulips. Are they to be planted or have they been dug up? There's no obvious sign of either task, except for a leaning spade. Behind them, three more women pass by on a lower level carrying boxes of flowers. Again, we wonder what is going on. The close file of women suggests organised, mechanical labour. It is a puzzling and cheerless scene, despite its vibrant colours, and despite the decorative flowering tendrils that hang low.

Goncharova's friend and biographer, the poet Marina Tsvetaeva, shared her preoccupation with Russian icons. In her poem Koli milym nazovu-ne soskuchish'sia! she refers to an icon known as the 'Three-handed Madonna'.

Image credit: The Icon Museum and Study Center, Massachusetts

The Three-Handed Mother of God

late 19th C, egg tempera on wood with silver oklad by unknown artist

It is claimed that this icon came about through inaccurate copying of a Greek icon featuring three hands: the third hand belonging to John of Damascus, severed as a punishment but miraculously reattached by Mary. The ghostly severed hand appeared in a late nineteenth-century Russian icon, and became confused with Mary, turning her into a tri-armed figure.

This intruding hand became a feature of icons, and may explain the hand pointing at the Rabbi and his cat in Goncharova's Rabbi with Cat (c.1912). Here it points at the sad Jew, less a blessing than a condemnation.

In the background, two more Jews carrying heavy sacks are likely fleeing a pogrom, confirming the menace of the pointing hand. The cat, enjoying the last moments of its owner's attention, is oblivious to this human horror.

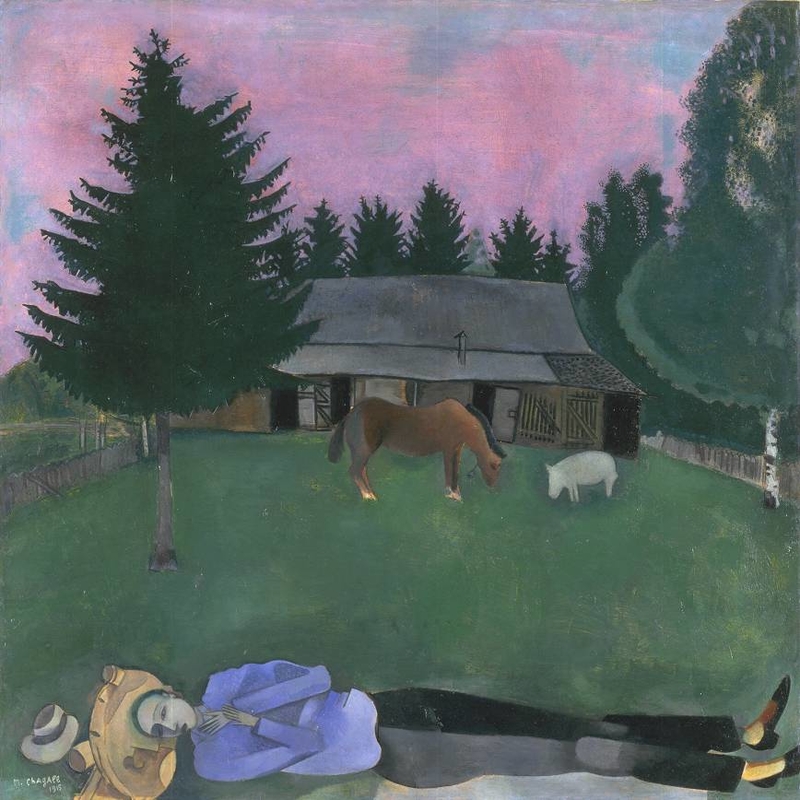

Goncharova painted The Forest around the time that Picasso's Dryad was bought by a Russian collector (1913), and this forest might be the domain of the Dryad, the tree nymph from Greek mythology. This shadowy, sinister place is made of the same angled planes and shards that characterise early Cubist works by Picasso and Braque in the years just before.

In Linen (1913), the starched stiff male and the delicate lacey female are presented side-by-side, embodied by their clothing. Each bears initials: Larionov's on the hem of the shirt on the left, Goncharova's on the flat iron. Ironing seems to have been the woman's task, even in this progressive household! The tightly arranged juxtaposition of objects overlying each other, often transparently, and the inclusion of bold text, are tropes of Cubist compositions by Braque and Picasso, while there's a Futurist flavour to the suggestion of animation – the blurring effect of repeated outlines – in the iron.

Goncharova's separation of gender roles in Linen reminds us that these were times less accepting of women artists. After a scandal-seeking newspaperman infiltrated a private 1910 exhibition, she was denounced (and stood trial) as a pornographer, essentially for having invaded the domain of male artists with her paintings of female nudes.

Despite such attitudes, Goncharova enjoyed considerable support from her artistic peers and achieved her position as a leading avant-garde artist without obvious hindrance. She was given unusual prominence in large monographic exhibitions in 1910, 1913 and 1914, although her St Petersburg exhibition in 1914 caused further outrage, drawing accusations of blasphemy for the style of her religious works, based on Russian icons.

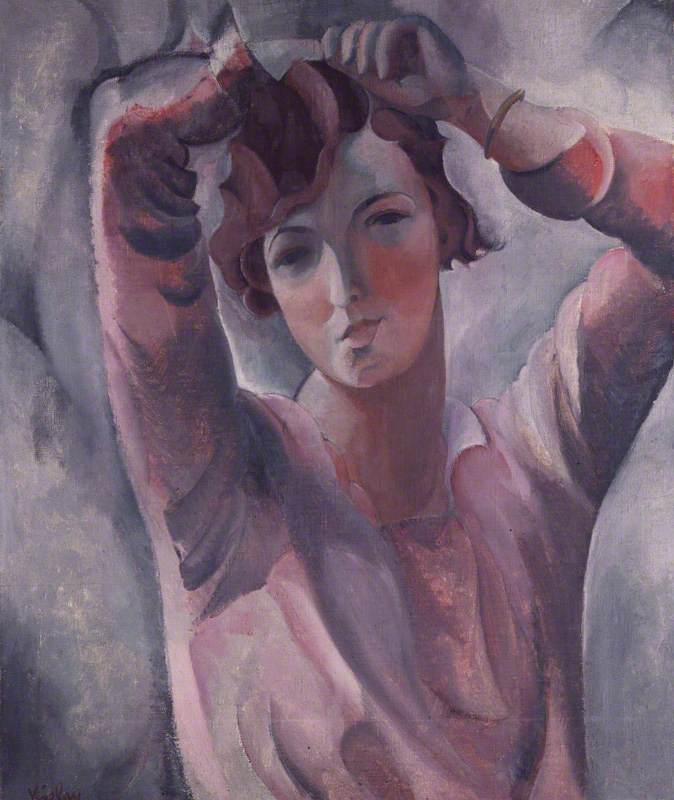

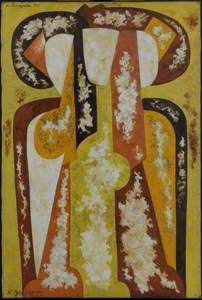

Goncharova and Larionov left Russia for good in 1915, to settle in Paris, a haven for émigré artists escaping revolution and war. Three Young Women (1920) comes from her long years there, when Goncharova was involved in theatre design and illustrating books using stencils, as its flat planes and bold outlines suggest. It has an emblematic quality, keeping with her work in Paris at this time. The three women lack distinguishing features, their bodies evoked by curves and lines: they might be identical triplets or Japanese geisha. Design matters more here than naturalism.

After settling in Paris – and for the rest of her working life – Goncharova's work was largely design, whether for costumes, stage sets or illustrations. It was in these designs that her Russian heritage found dazzling expression, notably for the Ballets Russes. Taking inspiration from Byzantine and folk art, these designs presented evocations of Russian Orientalism to an appreciative French audience.

That flurry of extraordinary art produced in the pre-war, pre-Paris years of the young century belongs to another time: of the avant-garde and gathering revolution, when wonderful work was made, and no inspiration nor style seemed beyond Goncharova's reach.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

John E. Bowlt (ed.), Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism 1902–1934, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2017

Matthew Gale and Natalia Sidlina (eds), Natalia Goncharova, Tate Publishing, 2019

Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art 1863–1922, Thames & Hudson Ltd, 2012

Jane Ashton Sharp, Russian Modernism between East and West: Natal'ia Goncharova and the Moscow Avant-Garde, Cambridge University Press, 2006

This content was supported by the Christie's Education Trust

![]()