Writing in 1892, the famous British opera singer Charles Santley (1834–1922) memorably claimed that musical performance was an art form 'written on air'. He explained: 'No sooner is it depicted than it is gone; while the poet's, painter's, sculptor's and architect's works remain.' This was especially true in an age before film or recording technology. Musical performance was ephemeral – and to some extent still is. A flick of a conductor's wrist. The flight of fingers across a keyboard. Joy flashing across the face of an audience member.

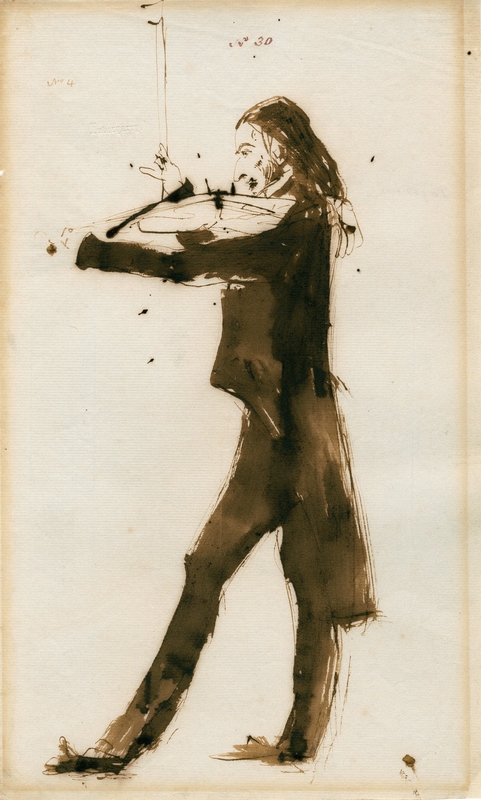

This heady mix of fleeting musical moments has long been a magnet for artists. Over the centuries, many have sought to capture musical performances on paper. Drawings – rapidly executed with just a pencil and sketchbook – have long been the favoured medium, offering an immediacy and fluidity that comes closest to capturing the moment.

Let's take a look at some of the different ways in which artists have captured musical performance.

Musical portraits: John Singer Sargent and Ethel Smyth

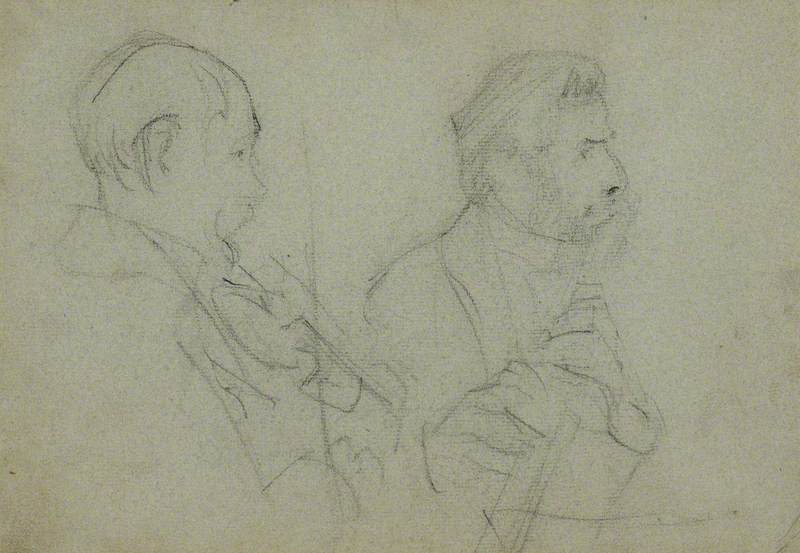

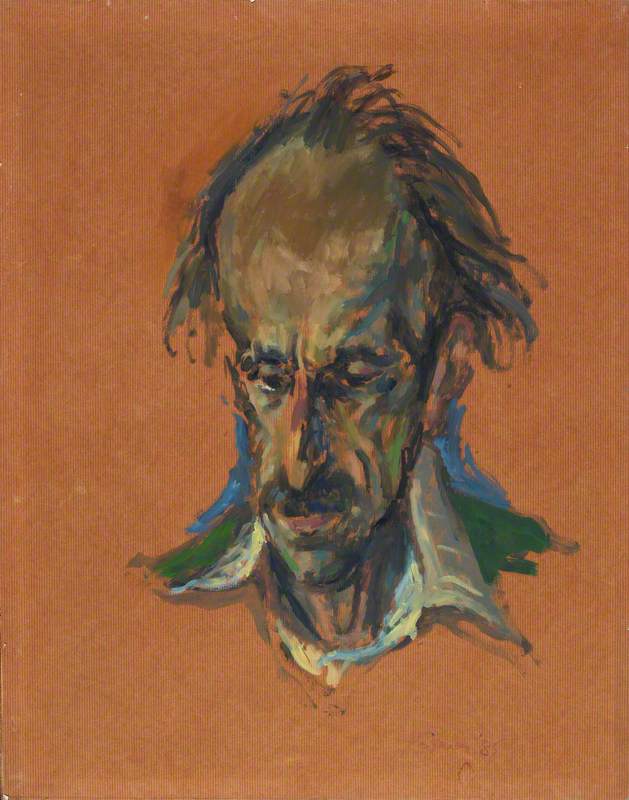

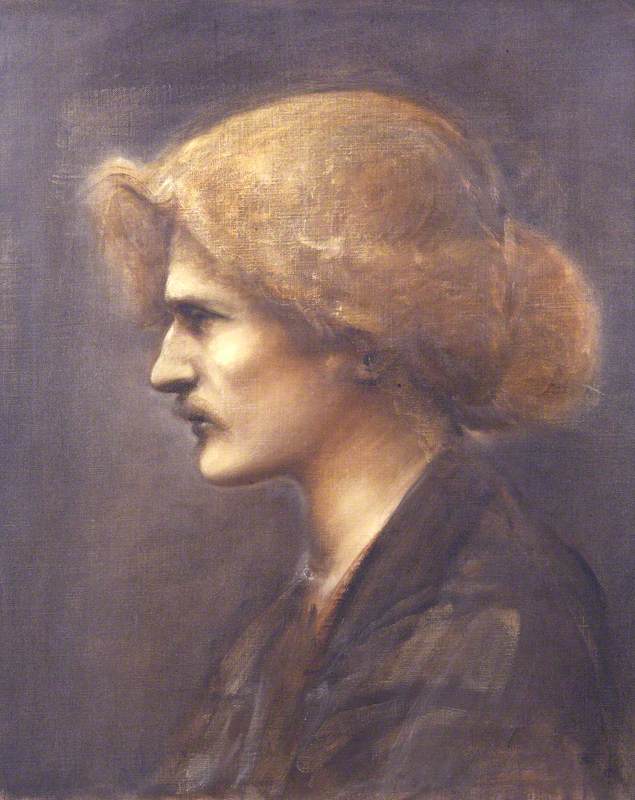

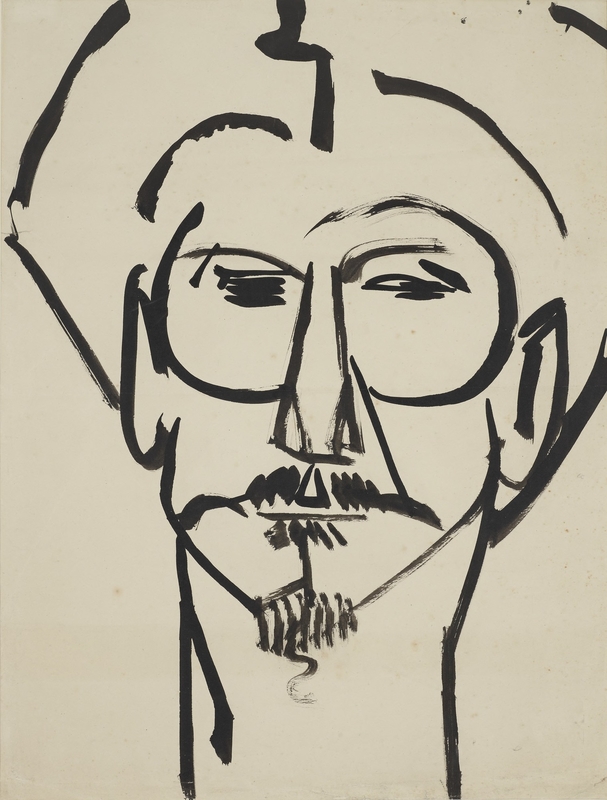

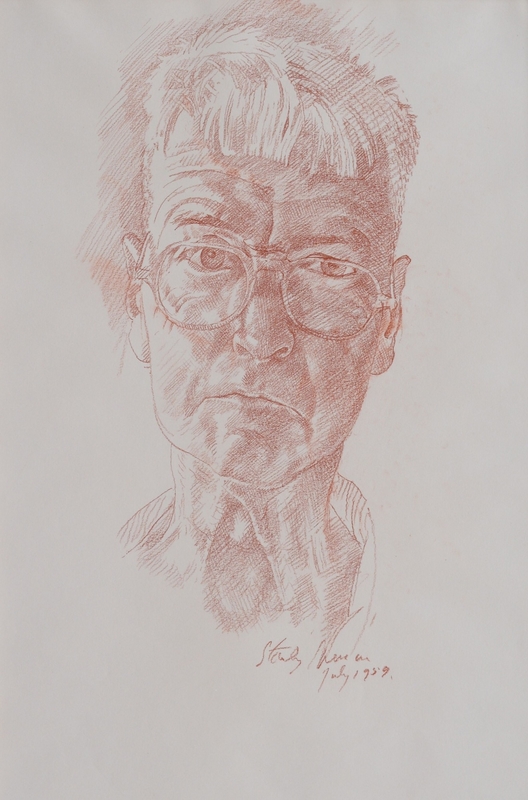

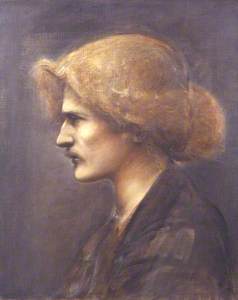

Celebrated portrait painter John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) was a musical connoisseur. An accomplished pianist who regularly attended concerts, he was friends with many of the most well-known composers and performers of his day. It is no surprise, then, that many of his subjects were musicians.

The majority of Sargent's musical pictures were charcoal portraits, which he referred to as 'mugs'. While the artist often produced this type of portrait for paying customers, many of those depicting musicians were un-commissioned – Sargent scholar Richard Ormond has called these Sargent's 'tribute to genius'.

The artist sometimes adopted an interesting method when capturing these portraits of performers. He would ask the sitter to sing or play as he sketched them. This was the case for Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) – a trailblazing female composer, writer and militant suffragette who had a series of passionate relationships with women, including Virginia Woolf (1882–1941) and Emmeline Pankhurst (1858–1928).

Smyth sat for Sargent in 1901, and left a fascinating account of this experience in one of her many volumes of memoir:

'All the time he kept on imploring me to sing the most desperately exciting songs I knew, such as Schubert's 'Gruppe aus [dem] Tartarus', Holmès's 'Chanson des Gas d'Irlande', and so on, crying out, as he hastily made dab after dab at his canvas: 'What's that?... What's that?' It took him only just over one and a half hours to draw what according to some of his colleagues – Charles Furse among the number – is one of the most remarkable singing portraits extant.'

Sargent captured Smyth in the grip of passionate inspiration. Her hands are stretched out at the keyboard in front of her, and her mouth is open mid-song. This portrait – vigorous and immediate – was produced quickly, Smyth describing the speed with which the artist completed his work. The result is a picture that seems to capture a moment, conveying the force of the musician's vitality. This same vigour can be heard in 'The March of the Women' – the rousing anthem Smyth composed for the suffragettes.

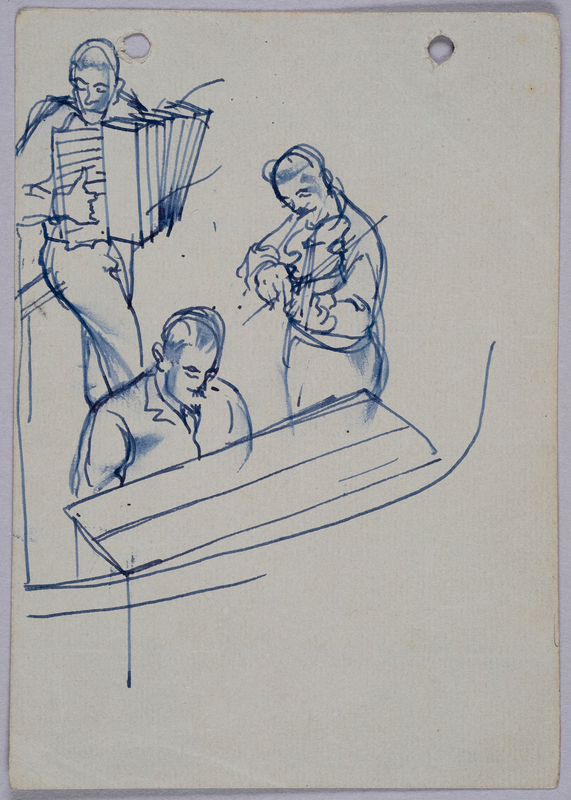

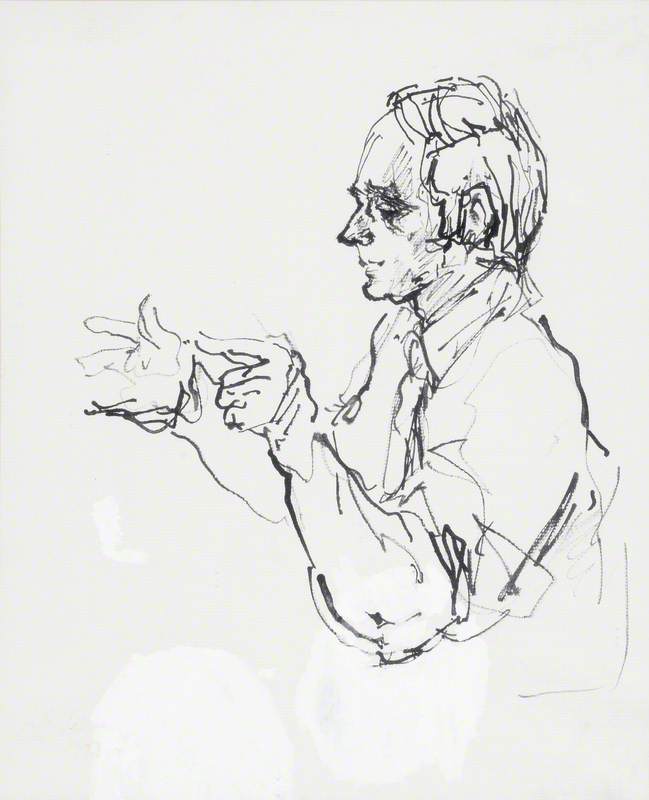

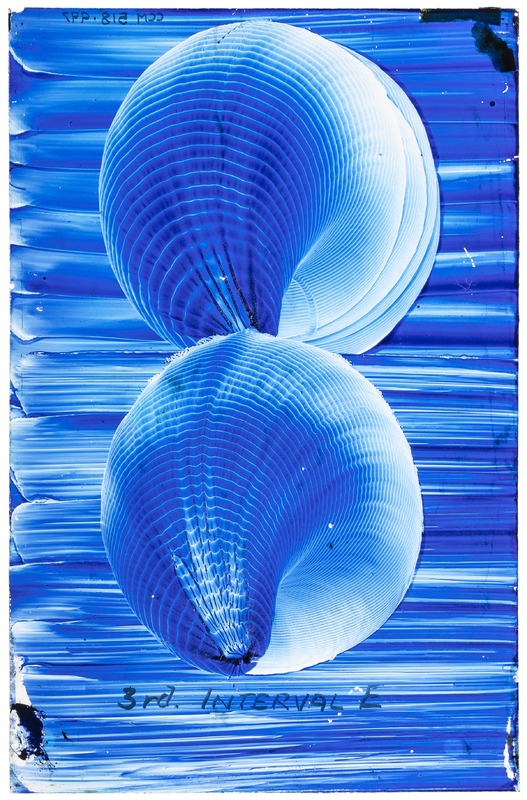

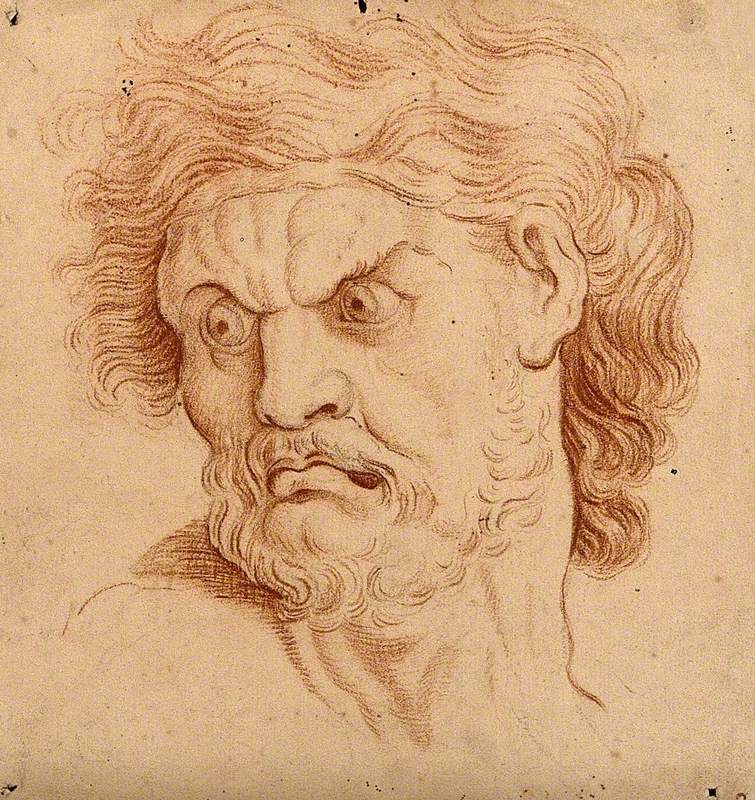

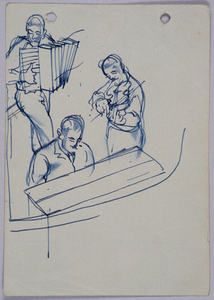

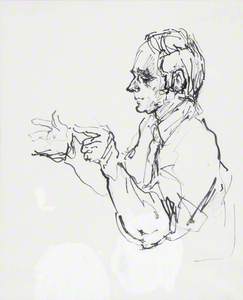

Music in motion: Milein Cosman

Later in the twentieth century, another artist made their name by capturing musicians in motion. Her name was Milein Cosman (1921–2017). Born in Germany to a Jewish family, she was – like many others – forced to flee when life became dangerous due to the rise of Nazism. Cosman moved to England in 1939, studying at the Slade School of Art and mingling with the lively community of émigré artists and musicians she found there.

Cosman later established herself as a professional artist with work at the Radio Times, soon meeting the music journalist Hans Keller (1919–1985) who she would eventually marry. Cosman and Keller's life revolved around music, and the artist therefore had access to endless musical rehearsals and performances. She seized these opportunities to sketch musicians at work and would produce hundreds of characteristic drawings that captured conductors and performers in motion.

Cosman would draw very quickly, seldom looking at the page, and producing many sketches in quick succession. She was particularly fond of capturing composers, being enthralled by their vigorous movements and unusual postures.

One composer and conductor she returned to many times was Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) – scholar Ines Schlenker has described Cosman's interest in drawing the musician as a 'preoccupation that lasted decades.'

Describing what she found so fascinating about watching Stravinsky conduct, Cosman said: 'I loved not only the intense athletic way he moved when he conducted, but the incessant changes of his face, in turn that of an absorbed musician, a bespectacled horse or a cuddly toy mouse.'

Cosman captured many of the most famous musical personalities of the twentieth century throughout her long life, including Maria Callas (1923–1977), Ralph Vaughn Williams (1872–1958) and Benjamin Britten (1913–1976). Not long before she died, she left the majority of her musical drawings to the Royal College of Music in London.

Musical studies: Edward Burne-Jones

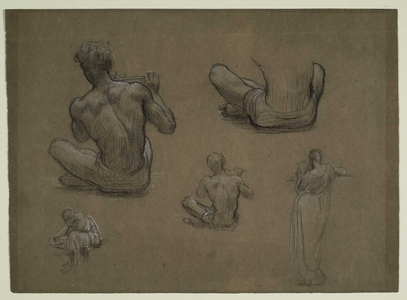

Study for 'Idyll': Male Figure Playing a Flute, Female Figures

c.1880

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

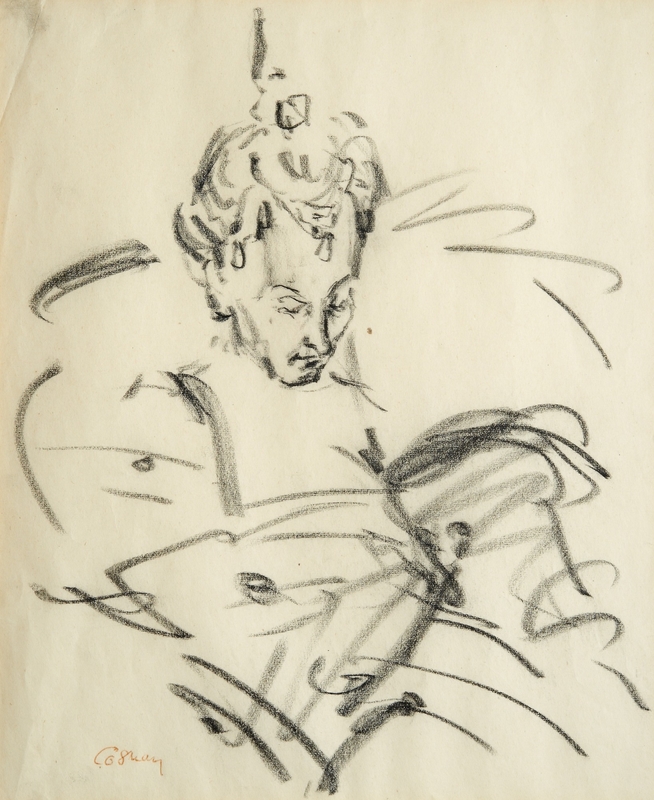

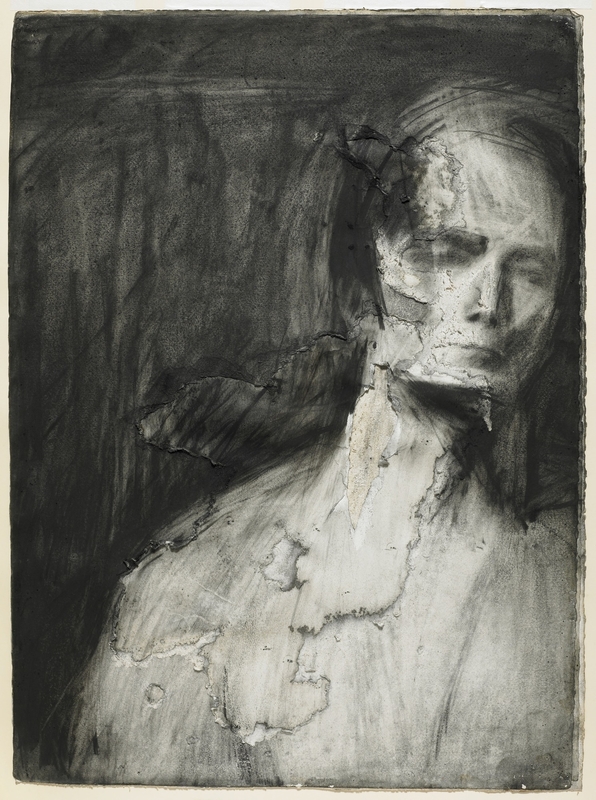

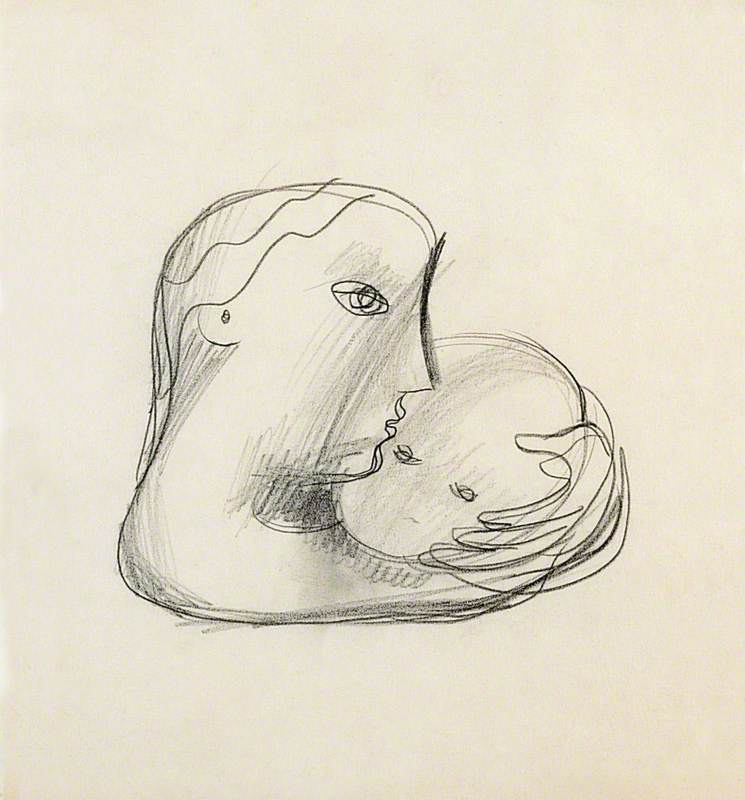

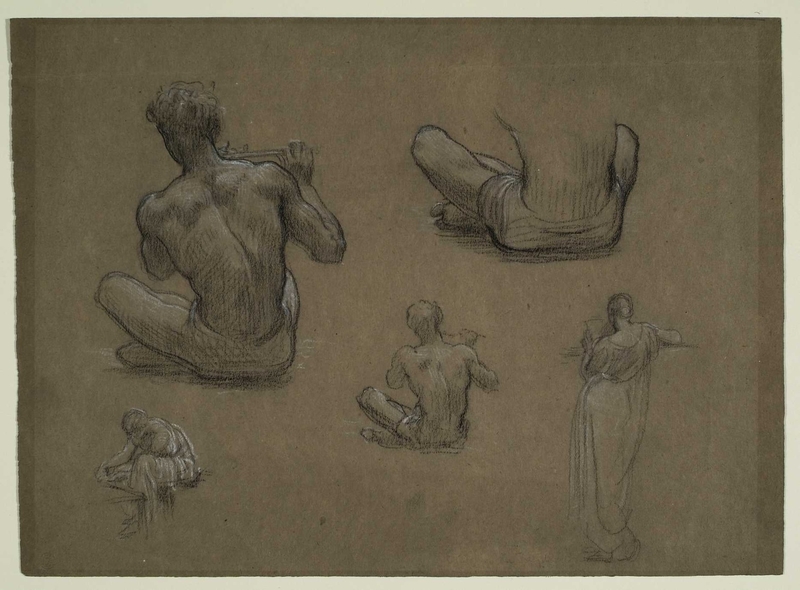

Sometimes artists have studied and sketched musicians to inform larger-scale works. These preparatory drawings offer us a glimpse at how artists sought to capture the spirit of musical performance – the exact angle of a finger on a keyboard, or the correct posture for an instrumentalist.

A particularly interesting example of this can be found in the work of Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) who was part of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. This ever-popular group of artists had many interesting musical connections. Like other members of the group, Burne-Jones painted and sketched famous musicians such as multi-talented piano virtuoso Jan Paderewski (1860–1941), who eventually became Prime Minister of Poland. Burne-Jones was captivated at Paderewski's shock of red hair, describing him as an 'archangel'!

Burne-Jones was also interested in piano decoration, and one of the instruments he painted beautifully with mythical figures is on display at the V&A in London. Other members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood found inspiration in music and opera, while Burne-Jones' friend, the painter-poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) had his words set to music by composers including Ralph Vaughan Williams.

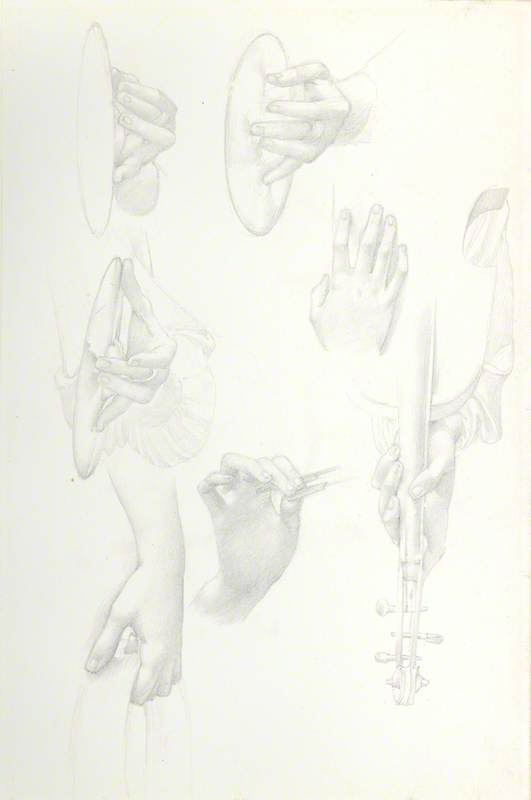

Studies of Hands with Musical Instruments for 'The Golden Stairs'

c.1878

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898)

Burne-Jones completed this study of musicians' hands to inform his well-known painting The Golden Stairs (1880). This ethereal painting depicts a group of women descending a staircase, playing musical instruments. Unusually for Burne-Jones, there was no literary source for this scene – rather than conveying a narrative, it sets an aesthetic mood.

His study of hands reveals the artist's preoccupation with creating a realistic sense of music-making. He has carefully studied how hands cradle the neck of an instrument, cup a symbol, steady a bow. Very different from Cosman's fluid sketches of music in motion, these are careful – almost scientific – studies.

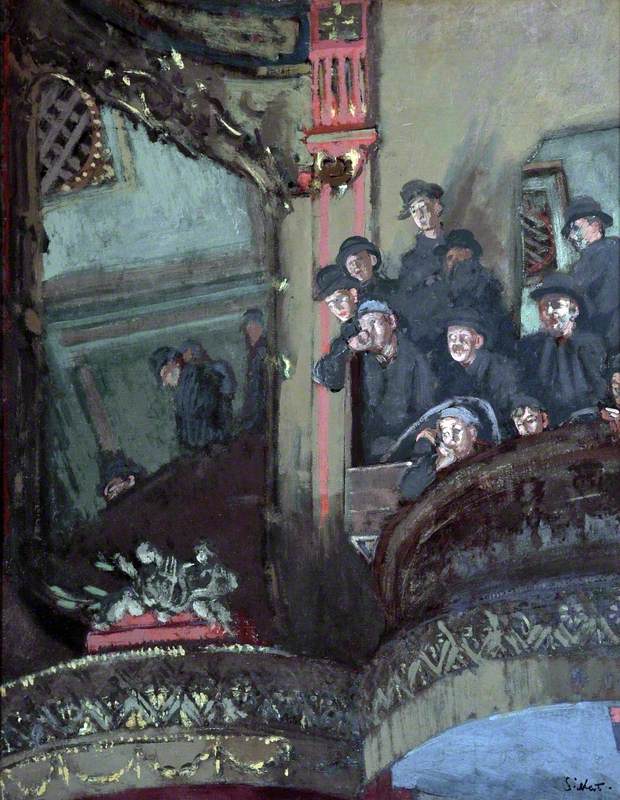

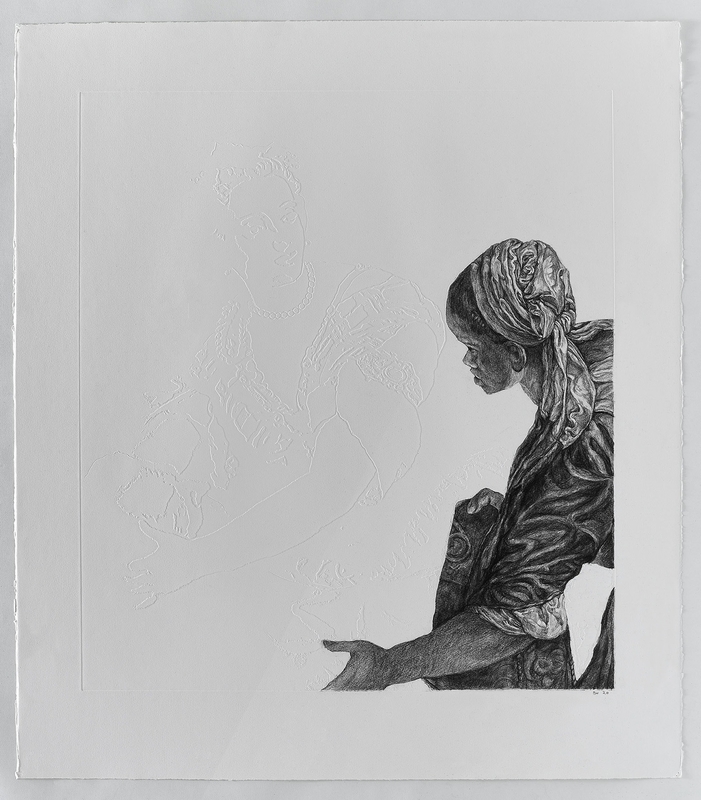

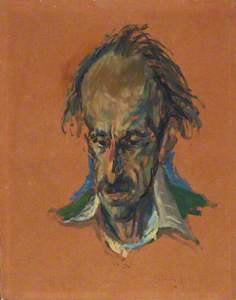

Painting performance: Walter Sickert

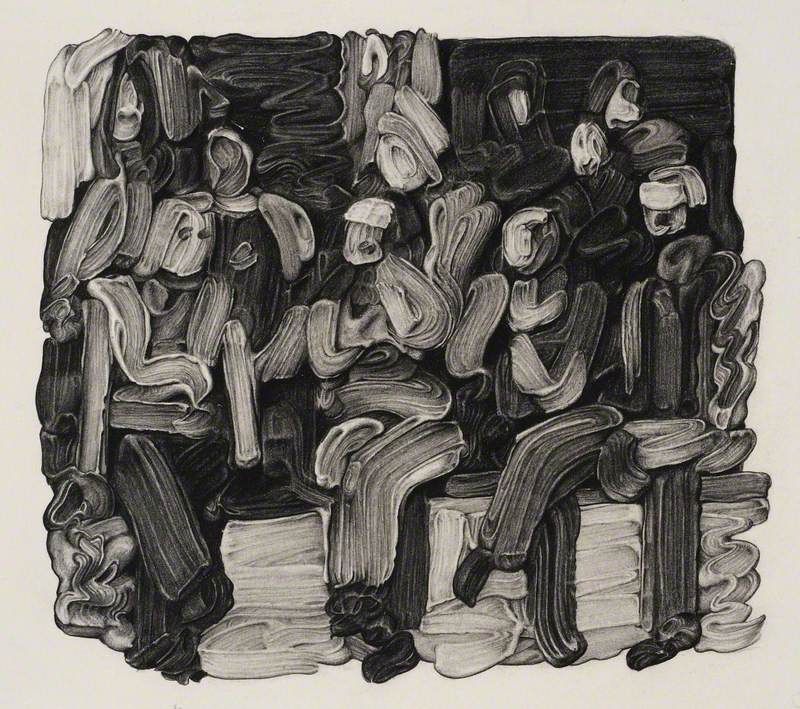

Another artist who was preoccupied with musical performance was German-born Walter Sickert (1860–1942). In this artist's case, his interest was less in the movement of musicians themselves than in the holistic experience of live performance.

Sickert spent a lot of time in the music halls of his local North London – an environment that was particularly familiar to him, as he had once worked as an actor himself. Theatres fascinated Sickert as they provided the subject matter for paintings that captured modern city life.

The artist was particularly fond of the Bedford Music Hall in Camden, where famous music hall star Marie Lloyd (1870–1922) loved to perform and Virginia Woolf could sometimes be spotted in the audience. Sickert referred to the Bedford as 'my old love.'

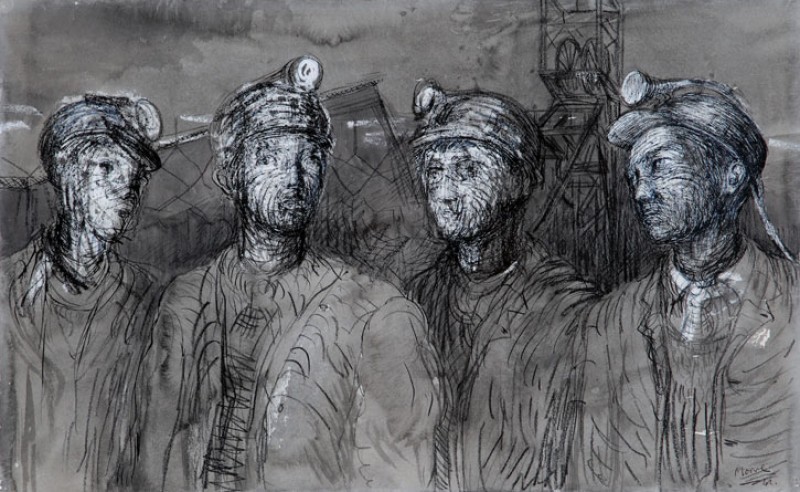

Study for the 'Three Drummers', or 'The Drummer Trio', or 'The Sisters X'

c.1890

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

At the theatre, Sickert would sit in the audience capturing the mood from different perspectives – sometimes up high in a gallery, sometimes low down on the floor. His drawings capture quick, kaleidoscopic glimpses of the music hall experience – the scrolls of decorative mouldings, the sweep of heavy curtains, the outstretched arms of a singer.

The New Oxford Music Hall, The New Bedford

c.1908

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

What Sickert was particularly interested in, though, was the audience, largely made up of working-class Londoners. He studied their dress, their expressions and their postures. Some look bored or tired, while others lean over the balcony in excitement.

In the paintings that he later worked up, using his drawings as a reference, there is a sense of juxtaposition between the rich, gilded interior of the theatre and the dark, somewhat drab, attire of the crowd. In these works, it seems that Sickert was sometimes more interested in the spectators than the spectacle.

Sickert's beloved Bedford closed in 1959 and was ultimately demolished. Like many of the other drawings explored here, Sickert's sketches capture something lost – musicians long dead, theatres long closed, voices that were never recorded, performances that were never filmed. The rapid, portable and reactive medium of drawing perhaps comes closest to recording the ephemeral experience of music – capturing what is 'written on air.'

Anna Maria Barry, art historian

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Richard Ormond, John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal, D. Giles Ltd, 2019

Charles Santley, Student and Singer: The Reminiscences of Charles Santley, Macmillan and Company, 1892

Ines Schlenker, Milein Cosman: Capturing Time, Prestel, 2019

Ethel Smyth, What Happened Next, Longmans, Green and Company, 1940