Hidden in the heart of Islington, North London, is a little-known gallery brimming with Italian art. The Estorick Collection showcases work from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From dynamic Futurist paintings buzzing with energy to quiet still life etchings, the gallery is a microcosm of Italy's artistic currents and trends during an extraordinary period when European art was turned on its head.

The artworks displayed here were once the personal collection of Eric and Salome Estorick. Since 1994 they have been on public view in a deceptively ordinary-looking house at 39a Canonbury Square.

While the permanent collection is most well known for its paintings and drawings, it also contains a number of sculptures by artists less well known in the UK – the likes of Medardo Rosso, Marino Marini, and the sole female representative in the collection, Giuditta Scalini. It is to these three that we will turn our attention, revealing the very specific character of modern sculpture in Italy.

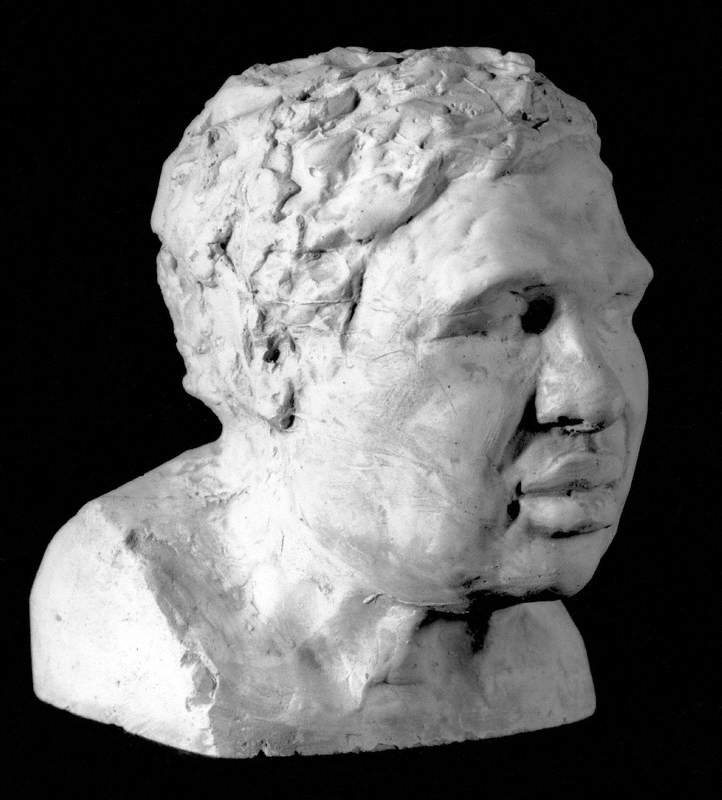

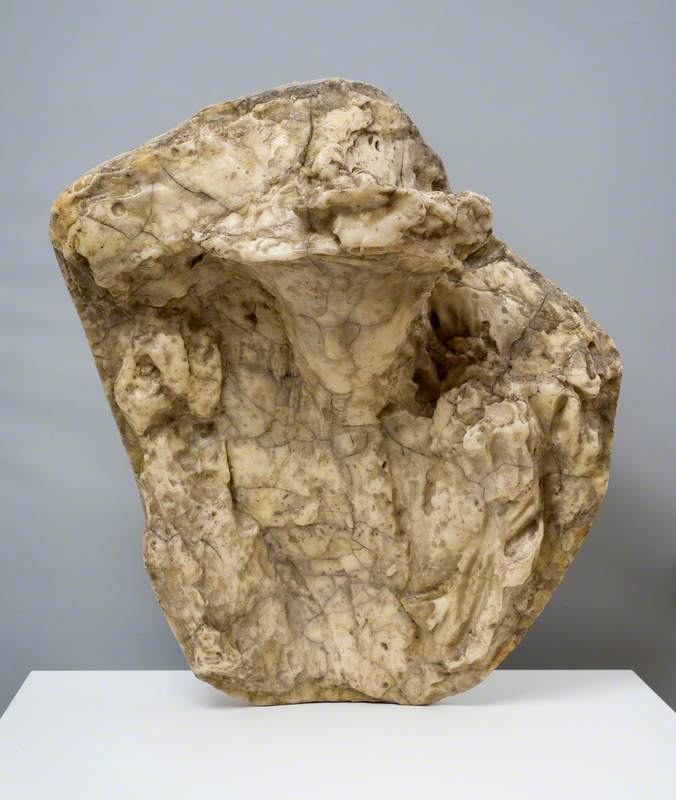

To look at a Medardo Rosso (1858–1928) sculpture is to experience a kind of pareidolia – that strange power of finding patterns in random data, like the man in the moon or a dinosaur among the clouds. The eye finds a figure so subtle that the mind doubts it is really there, almost expecting it to disappear.

Image credit: Estorick Collection, London

Impressions of the Boulevard: Woman with a Veil 1893

Medardo Rosso (1858–1928)

Estorick Collection, LondonRosso was born in 1858 in Italy. He shunned the rigid, monumental forms of sculpture that had come before him, choosing to work with materials like plaster and wax. His works often retain a sense of the slipperiness and fluidity of those materials. He aimed to capture fleeting moments of life and in this way echoed the painters of his day. It was a time when the French Impressionists were revolutionising art by painting outdoors to catch the changing light.

Rosso built up some notoriety in France and relocated to Paris in 1889, enmeshing himself in the artistic circles of that city.

Image credit: Estorick Collection, London

Impressions of the Boulevard: Woman with a Veil 1893

Medardo Rosso (1858–1928)

Estorick Collection, LondonThis work, Impressions of the Boulevard: Woman with a Veil, was made roughly twenty years after Monet's renowned Impression, Sunrise, the painting that gave a name to a movement. Here, Rosso draws a clear link between his work and that of the famed French painters.

The subject matter of Rosso's work also mirrors that of the Impressionists. It recalls the figure of the 'flaneur', the nineteenth-century well-to-do young man wandering the streets of Paris and observing rather than participating in the life around him. The sculpture is a glimpse of that life, a passing moment of the everyday immortalised in sculpture. Despite the time it must have taken to make, there is an almost photographic sense of speed, as though she were snapped just hurrying by.

Image credit: Estorick Collection, London

Impressions of the Boulevard: Woman with a Veil 1893

Medardo Rosso (1858–1928)

Estorick Collection, LondonShe appears to hold the veil above her head with just the vaguest idea of a raised arm. Her downward gaze and angled torso suggest she walks hastily, perhaps fleeing from an unexpected downpour. The sculpture feels at once prehistoric and timeless. The textured, grubby surface brings to mind cave walls, cliff faces and ancient stalactites, naturally formed over thousands of years. At the same time, the wax used to create this snapshot is only ever degrees away from disintegrating. She is something akin to a memory – indistinct, fragile, at risk of being lost.

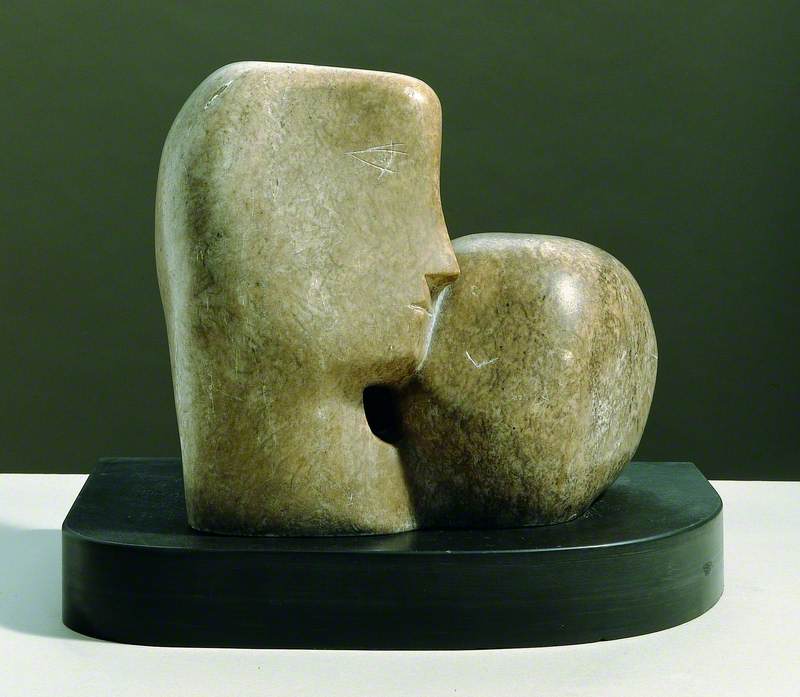

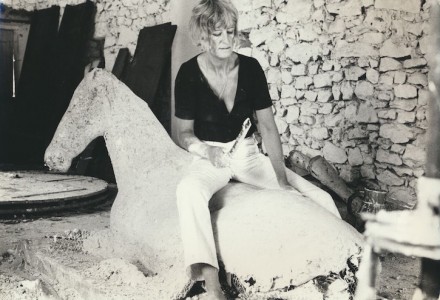

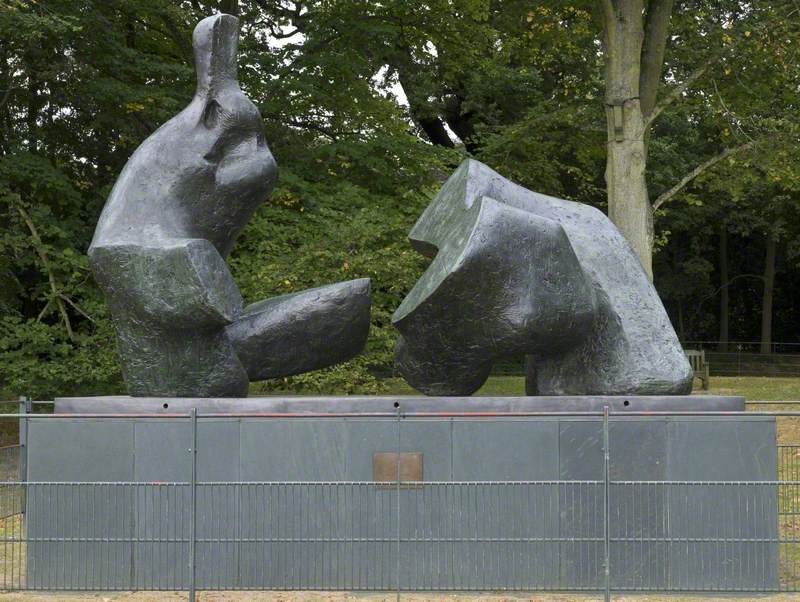

On the surface of things, the work of Marino Marini (1901–1980) could hardly seem more different to Rosso's. Marini was born in Tuscany in 1901 and his preferred medium, cast bronze, carries a weight of history as well as material. We are used to seeing bronze as the material of monuments and memorials. It was a technique used as long ago as ancient Greece and Rome and some bronze statues of that period still survive today. Unlike Rosso's, Marini's sculptures feel permanent, like they were meant to last.

Despite this, they are not without elegance and movement. This work is a maquette, or model for a larger sculpture – one in a series of works depicting riders thrown from their horses. It exhibits Marini's typical textured surface, an effect he preferred to the smooth polished finish of some more traditional bronze works.

Throughout Marini's career, he returned again and again to the equestrian statue – a motif that, like his material, has a long history in art, reaching back through the Renaissance to antiquity. The different ways he tackled his recurring subject reflected his feelings about the world around him.

His work from the 1930s featured upright, slender, nude, male riders on rigid and stationary horses, but as time went on his approach became more abstracted and imbued with forceful energy and emotion.

In this work the horse's neck is elongated and strained, reaching up in pain or terror. Its legs appear almost mutilated, relegated to truncated fins, while the rider is flung back, arms outstretched in a gesture of ecstasy that Marini often used. The gesture has been seen as representing the initial enthusiasm at the end of the Second World War, but this optimism is thrown into question by the clear anguish of the horse.

If the classical image of rider/horse relationship can be said to convey a sense of harmony, balance, and control, this sculpture suggests a world gone wrong, chaotic and uncontrollable. Marini didn't fight during the Second World War, but it was a major catalyst for his change in approach. Like many other artists, the horrors of the war, together with the uncertainty of the immediate post-war years, invaded his artistic practice. He once described seeing people in Milan fleeing on horseback from the flames of the city – an image that profoundly changed the way he viewed his favoured subject.

While Marini is well known in Italy and has works in collections around the world, the same cannot be said of Giuditta Scalini (1912–1966). She is the only female artist in the Estorick Collection and information on her is scarce, but we do know she was born in Como in 1912.

She was the second wife of the painter and sculptor Massimo Campigli and the two sometimes worked together.

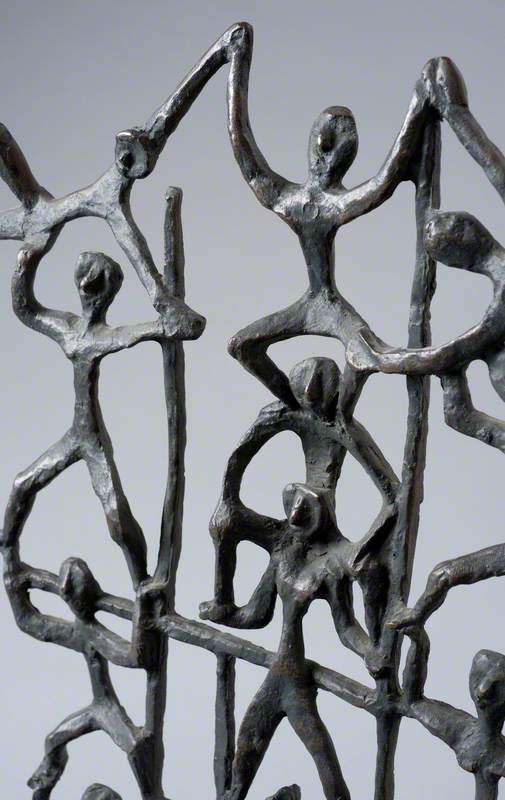

This sculpture is titled Acrobats. It displays the influence of an ancient form of art.

Scalini was influenced by the Nuragic civilisation of Sardinia which flourished thousands of years ago. The small bronze statues typical of Nuragic civilisation art depicted scenes of everyday life as well as characters from various social classes, animals, warriors and gods.

Scalini's small-scale figurines display the same delicate proportions and slender limbs as the Sardinian statuettes. Despite being cast in bronze, her small figures have a lightness and elasticity as though they might just spring apart and into a new precarious formation. Each figure is subtly different, pared down to basic features yet still full of individual personality.

While clearly identifiable as a tower of balancing performers, Scalini's sculpture also functions of the level of pattern and decoration. The repeated, almost-symmetrical formation of figures casts beautiful geometric shadows on the white gallery walls – patterns which change throughout the day. They create a sort of double artwork possible only with sculpture.

These three artists, though very different, all sought a change from the traditional art that had come before them. Together they give a real taste of what Modernism looked like in Italy, the way artists were influenced by movements abroad, the way they reacted to huge global events, and the way they looked to the distant past for ways to inspire their present.

Kate Devine, art historian