Rising to prominence at a time when the art world was far less international than today, it is understandable that the American painter Milton Avery (1885–1965) failed to make much impact in Britain. However, he has long been respected in his homeland for his trademark use of colour and for providing a bridge between late nineteenth-century Impressionism and the modernist revolution of the Abstract Expressionists.

Husband and Wife

1945, oil on canvas by Milton Avery (1885–1965)

While stylistically connected to those two genres, Avery stubbornly followed his own path and avoided categorisation. In 1952 he stated: 'I never have any rules to follow. I follow myself.' Yet the New York-based painter developed close relationships with several stars of mid-twentieth-century art, inspiring the groundbreaking styles of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman.

With a major show devoted to Avery opened at the Royal Academy, London, many of us can now learn what the Abstract Expressionists valued in his oeuvre. Indeed, 'Milton Avery: American Colourist' is the first time a public institution has put on a solo exhibition of his work in Europe.

Blossoming

1918, oil on board by Milton Avery (1885–1965)

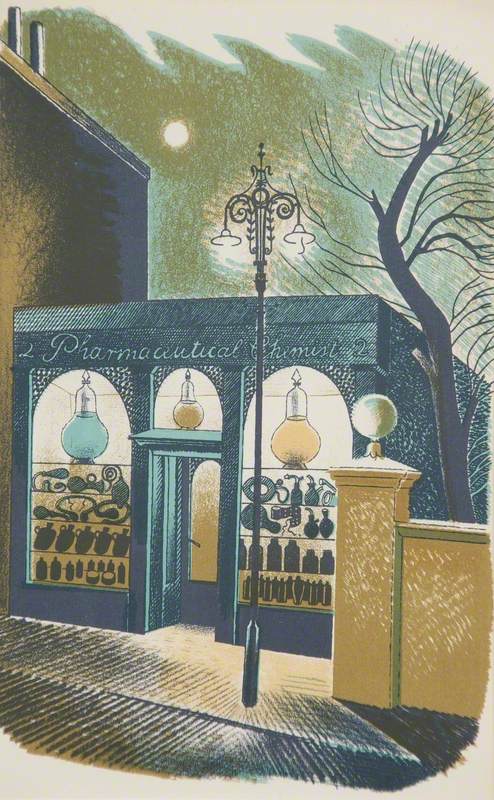

After his working-class family moved from Altmar, upstate New York, in 1898, Avery was raised in Hartford, Connecticut, where he first took art classes to learn commercial art, later encouraged by a tutor to transfer to life-drawing. During a 15-year period of training, Avery came under the spell of American Impressionists, especially John Henry Twachtman and Ernest Lawson, who had themselves spent summers working in the east coast state.

From them, the painter adopted the practice of painting outside, en plein air, as he too explored Connecticut, inspiring early landscapes. Avery soon showed an eye for colour and the ability to reproduce the effects of light, especially through the use of palette knives to spread thick pigment smoothly.

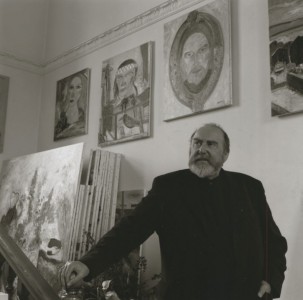

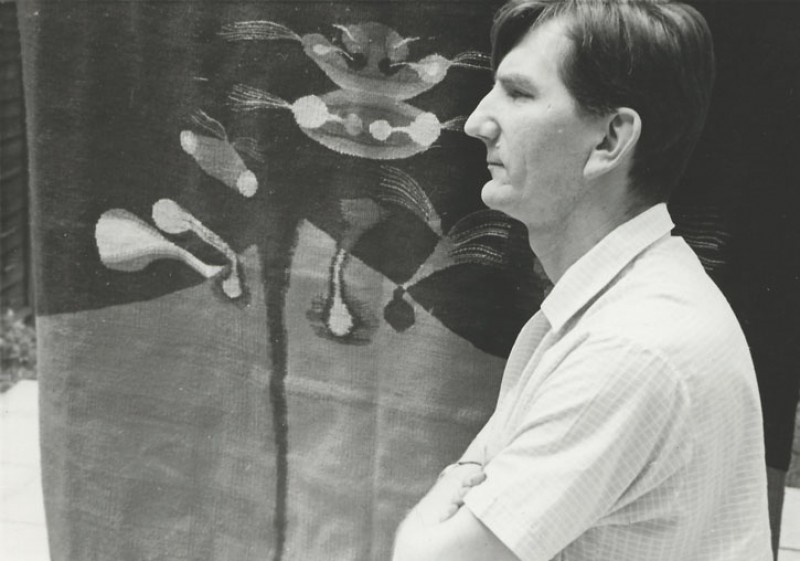

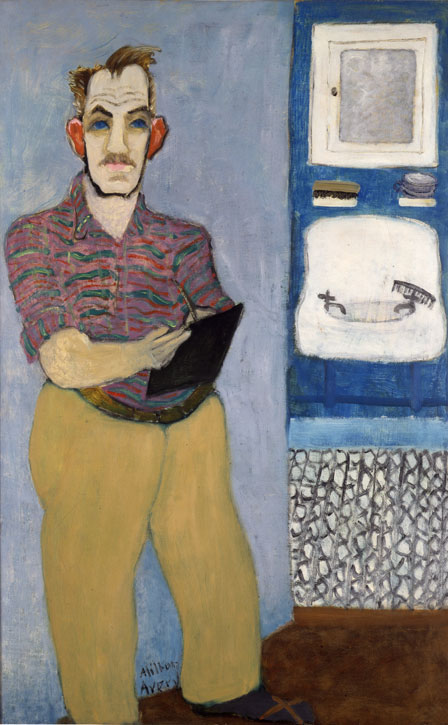

Self-Portrait

1941, oil on canvas by Milton Avery (1885–1965)

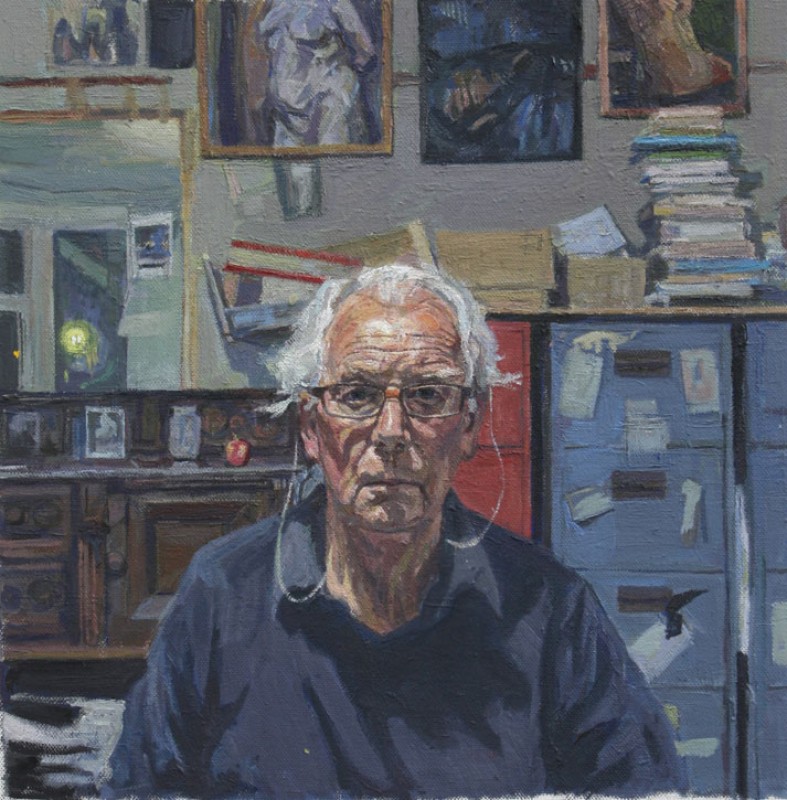

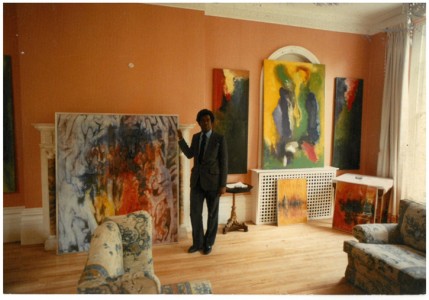

Notably prolific, Avery moved to New York in 1925 and a year later married Sally Michel, a younger artist who took on commercial work to support him. He began to produce cityscapes, though preferred painting in locations such as Central Park and Coney Island, with meadows and beaches reminiscent of his childhood haunts. He also focused on portraiture, creating representations of family, fellow artists and numerous self-portraits, one from 1941 showing him as confident and determined.

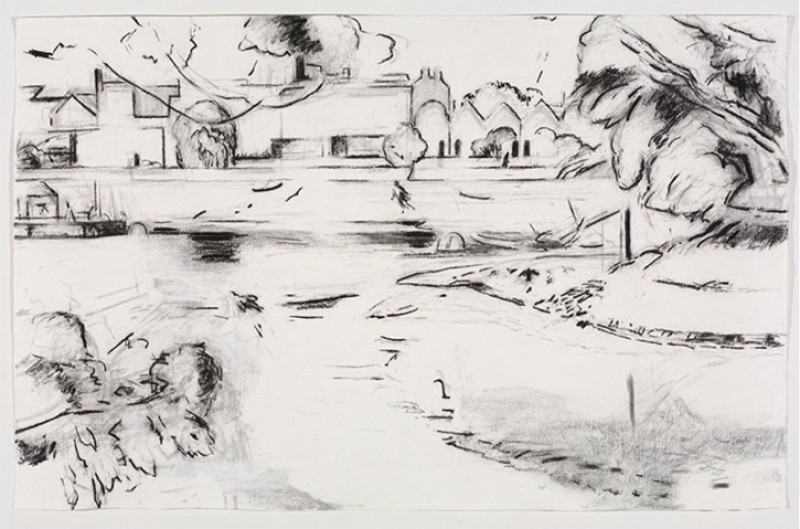

Little Fox River

1942, oil on canvas by Milton Avery (1885–1965)

In New York, Avery's palette became more muted, while he also established a habit of spending summers in areas of natural beauty, such as the artists' colony MacDowell, in Peterborough, New Hampshire. As his daughter March Avery Cavanagh, an artist herself, explains in the catalogue of the Royal Academy show, he continued working outdoors, sketching in pencil and painting in watercolours on paper, but would develop these scenes into oils on canvas at home the rest of the year.

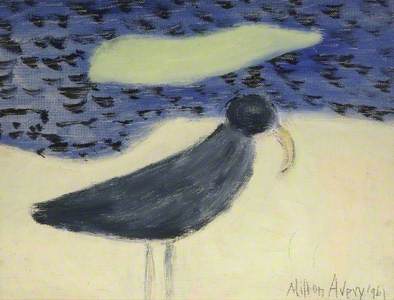

Working through the Depression and the Second World War, he also learnt to be abstemious with materials, thinning his paint with turpentine and using whatever surfaces came to hand, such as the card for Bird and Sandspit (1961).

During the early 1940s, he moved away from formal portraits, though figures remained important in his work. By this stage, institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) had launched and were introducing him to European developments such as Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, which would have a role in shaping his development. He was also part of a vibrant creative scene, spending time with many artists and even teaching Marcel Duchamp to play pool.

Seated Girl with Dog

1944, oil on canvas by Milton Avery (1885–1965)

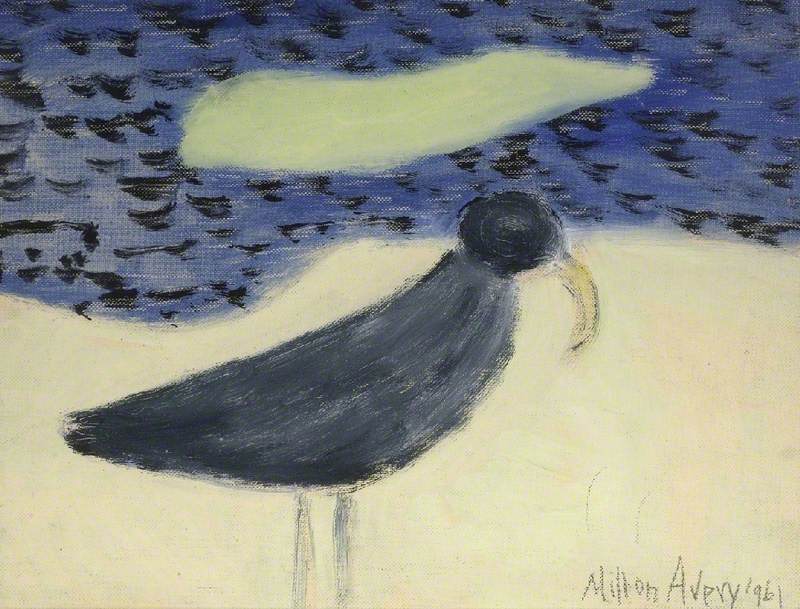

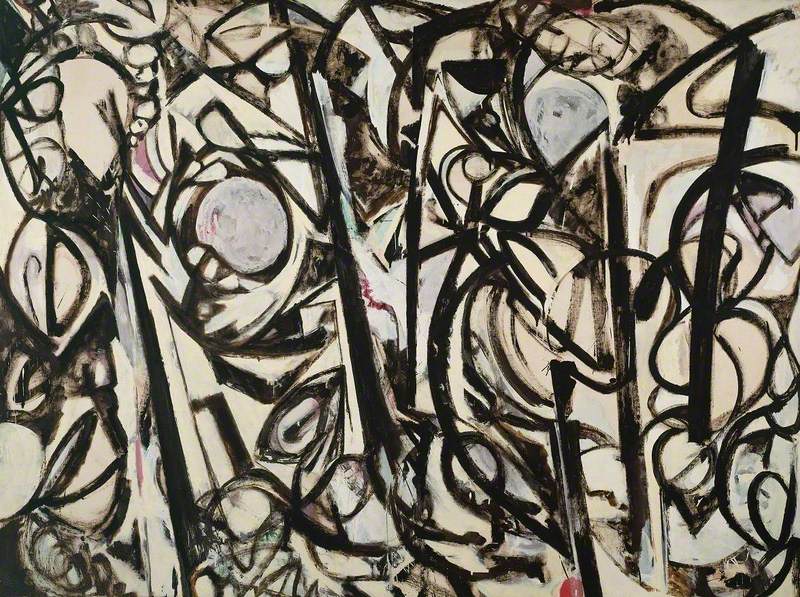

Avery's key period of innovation dates from the mid-1940s when the artist began to use thinner, more fluid applications of oil. He flattened the planes of his paintings to create semi-abstract forms made up of complementary, luminous tones. Instead of relying on perspective, Avery's choice of colours hinted at depth and atmosphere. It was this harmony and balance between them that impacted younger artists such as Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb.

Avery appeared in a group show with the former in 1928 and the two became firm friends, the younger painter introducing him to Gottlieb and then Newman, another practitioner of the Color Field style of abstract painting that emerged in New York during the 1940s.

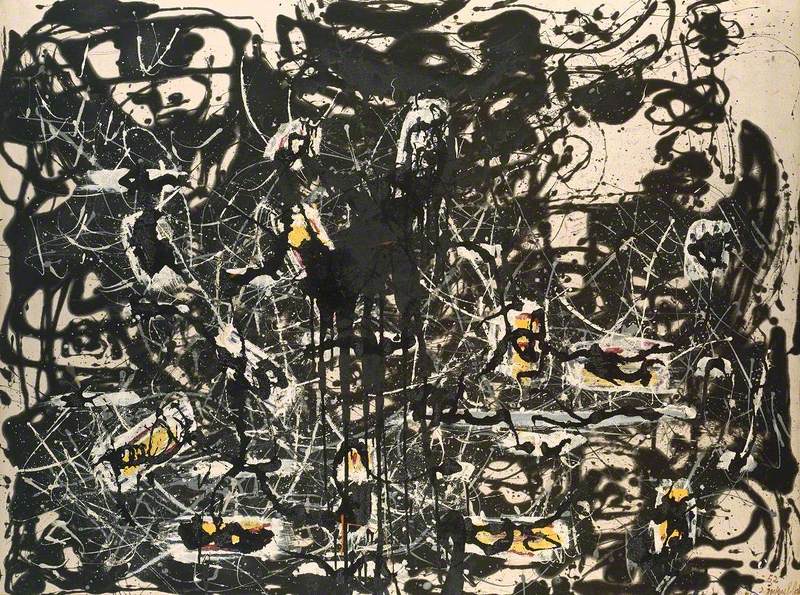

In 1952, Avery received his first large-scale retrospective at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Later that decade he turned away from figurative work to focus on landscapes, especially serene seaside scenes derived from trips to the US east coast, returning regularly to familiar locations, among them Gloucester, Massachusetts, Vermont and Maine, each impacting on his evolving use of colour. He continued to reduce the amount of detail further while employing less natural tones to provide variety and contrast, works such as the stark Black Sea (1959) showing his debt to European Modernists, in particular Henri Matisse.

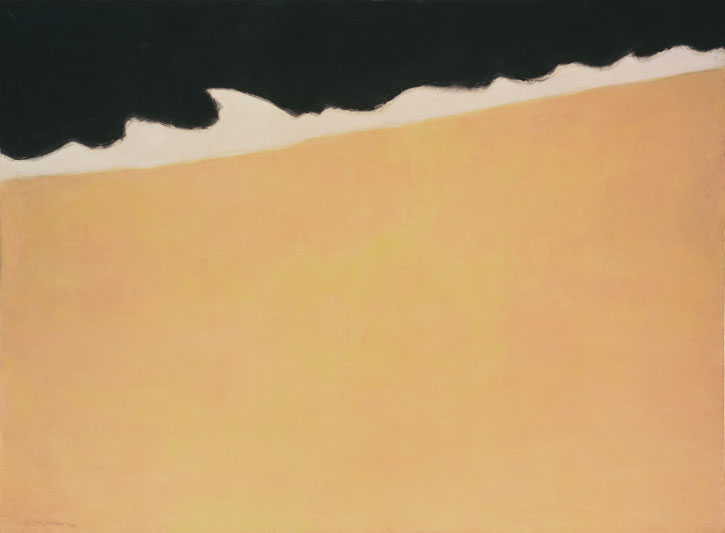

Black Sea

1959, oil on canvas by Milton Avery (1885–1965)

Known for being taciturn, albeit with a dry wit, Avery rarely gave interviews, though in a 1951 catalogue for a group show, he was quoted as saying, 'I like to seize one sharp instant in nature, imprison it by means of ordered shapes and space relationships to convey the ecstasy of the moment. To this end I eliminate and simplify, leaving nothing but colour and pattern.'

Despite his affection for European masters, Avery only made one trip to the old world, touring London, Paris and the French Riviera in 1952. By then, he had been weakened by a serious heart attack two years prior, though he continued to produce some of his finest work. Later in the decade, the painter found inspiration in Cape Cod, spending the summers of 1957–1959 in the artistic enclave of Provincetown, where he composed the initial sketches for Yellow Sky (1958).

Until this point, Avery had rarely been praised by critics such as Clement Greenberg, a major champion of Abstract Expressionism. Now, though, he was recognised as a key influence on this movement, leading to a major show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in 1960. In turn, he also found inspiration from the generation he himself had influenced – not only in the move away from figuration but also in working on a larger scale, as with Boathouse by the Sea (1959), one of his biggest canvases.

Boathouse by the Sea

1959, oil on canvas by Milton Avery (1885–1965)

Avery's works are now held by many major US institutions, among them MoMA, the Whitney, and New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art. A full retrospective, including much early work that had rarely been displayed, was only held at the Whitney in 1982, so there remains an opportunity to remind art lovers of his particular genius, RA curator Edith Devaney believes.

'It is probably true that over the past few decades the public's appetite for figuration ebbed a little in favour of abstraction,' she says. 'This may have played some part in Avery's work not being the subject of focus since the 1980s. With figuration back in the ascendancy it feels like a good moment to reassess his career and enduring influence.'

Rothko, though, was sure of Avery's importance. In a memorial address for his old friend, delivered in 1965, he described him as a 'great poet-inventor', saying, 'there have been others in our generation who have celebrated the world around them, but none with that inevitability where the poetry penetrated every pore of the canvas to the very last touch of the brush.'

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Milton Avery: American Colourist' is at the Royal Academy, London, until 16th October 2022