This year marks the centenary of the artist Michael Ayrton (1921–1975), whose paintings, drawings and sculptures challenged both traditional and contemporary expectations and brought him controversy and admiration in roughly equal measure.

Ayrton was the only child of Gerald Gould, classicist, poet and journalist, and Barbara Ayrton-Gould, suffragist and Labour politician. Her parents, William Ayrton and his second wife, Hertha Marks, were both distinguished physicists; Ayrton thus inherited a rich blend of arts, science and socialist politics on which to base the acutely observed, imaginative and compassionate humanism which lies at the core of his work in all media.

He was always aware that his decision to become an artist was not the path his parents expected of him. Nevertheless, at the age of 14, he abandoned formal education and set out on his chosen path. In Vienna, under the care of a distant cousin, notable eccentric and art critic Amelia Levetus, he spent hours in the Albertina copying the large collection of German Masters there, especially Albrecht Dürer. As well as shaping his early style, these encounters convinced him of the centrality of drawing – 'the process by which experience is simultaneously ordered and enlarged' – and for the rest of his life he drew every day.

After an abortive attempt to join the anti-fascist forces in Spain despite being well under recruitment age, Ayrton briefly attended various London Art Schools before settling in Paris, sharing a studio with John Minton. Influenced by Picasso's Blue Period and by the edgy romanticism of Eugène Berman and Pavel Tchelitchew, his paintings of this period have an emphatic linearity, presenting enigmatic situations that suggest fragments of broken narrative, as in The Fortune Teller (1941).

These early works were signed 'Michael Ayrton G.' He adopted his mother's surname shortly after his father's death as more suitable for an artist (and, he later said, it put him at or near the top of alphabetical lists for mixed exhibitions!). He discarded the 'G' by the later 1940s, although Gerald Gould's influence remained significant for the rest of his life.

The year 1940 found Ayrton back in London, cut off from the eclectic influences he had enjoyed in Paris and caught up in the resurgent nationalism which swept through British art of the time. Called up into the RAF in 1941, Ayrton was discharged on health grounds. He took a teaching post at Camberwell, and embarked on the wide range of activities that won him the (not always approving) epithet 'Renaissance Man', which followed him through the rest of his career.

Following the success of his designs for John Gielgud's production of 'Macbeth', undertaken in collaboration with Minton, he worked on a number of theatre, ballet and opera designs. He also illustrated books, published a history of British drawings, took over from John Piper as art critic of the Spectator, and took part in the BBC's 'Round Britain Quiz' as the youngest member of the Brains Trust.

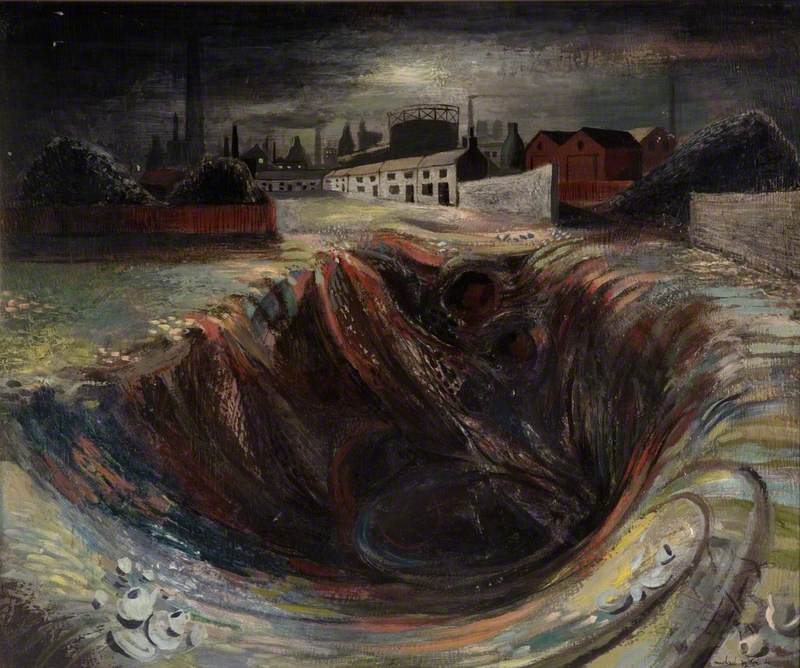

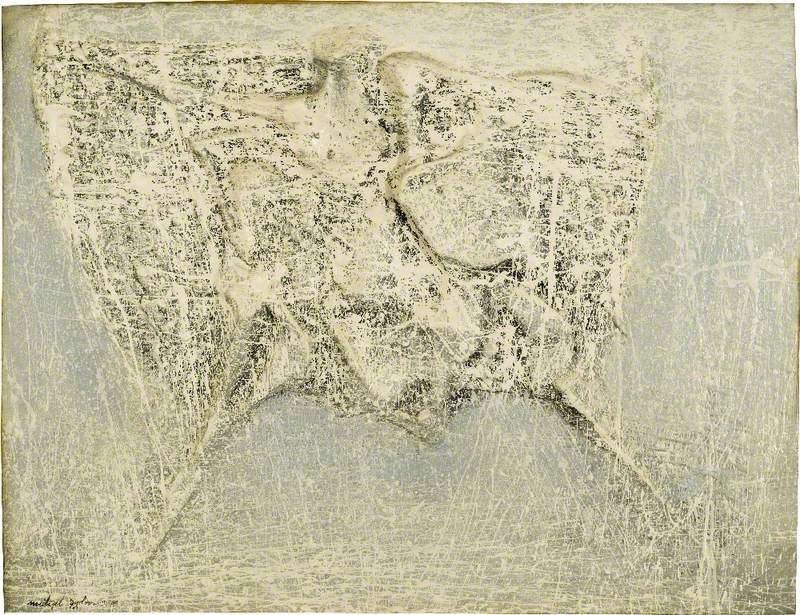

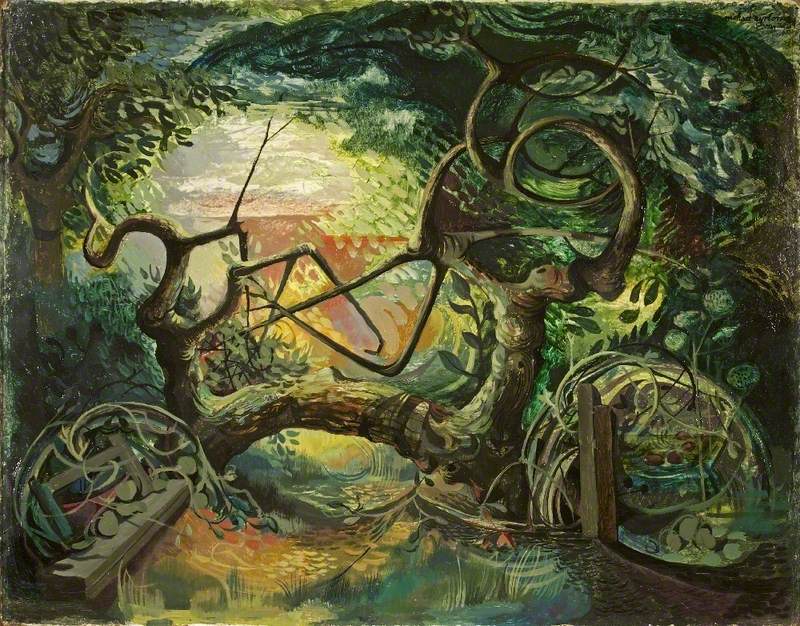

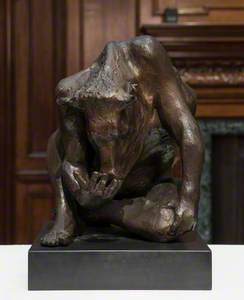

Study on the Theme of the Temptation of Saint Anthony

1943

Michael Ayrton (1921–1975)

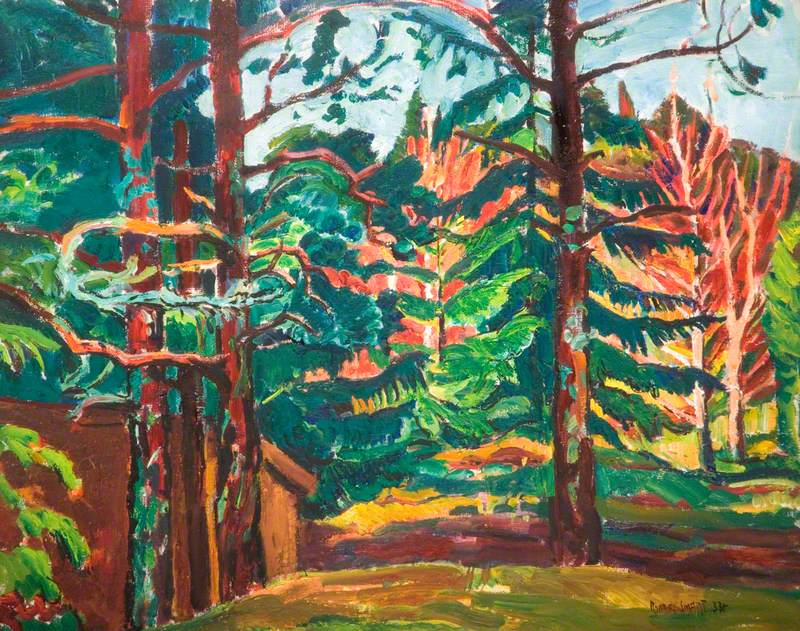

None of this distracted him from painting. He became friendly with Graham Sutherland, and worked alongside the loosely affiliated group of painters associated with the British Neo-Romantic movement, using landscape painting to express the trauma and isolation of the war years.

Ayrton's landscapes are evocative and disturbing: powerful, brooding compositions such as Winter Stream (1945), where a fallen tree rears dragon-like above the racing water, or the enigmatic The Tip, Hanley (1946) scattered with shards of broken pottery. A fascination with the occult produced the series of paintings based around the legend of Saint Anthony, the saint imagined in fantastic landscapes which writhe in an echo of his torment: Study on the Theme of St Anthony (1943).

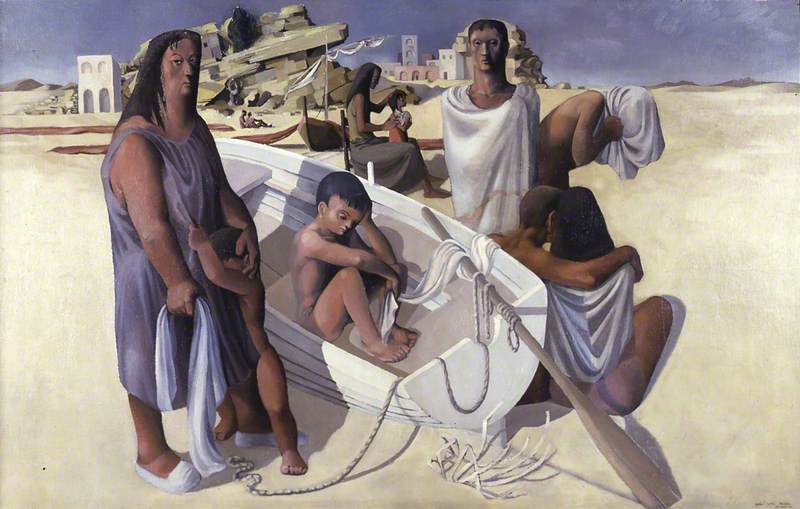

The end of the Second World War opened the Continent again to painters eager to regain the Mediterranean light, literal and artistic, from which they had so long been barred. Ayrton went to Italy, where he fell under the spell of the Renaissance masters, especially Masaccio and Piero della Francesca, fascinated by the 'monumental images, timeless, impersonal and yet human... filled with secret communication and unspecified drama' that he found in their works.

His paintings became more sculptural, culminating in the majestic Captive Seven (1950), painted as part of the '60 Pictures for '51' exhibition organised by the Arts Council during the Festival of Britain. Observation, geometry and symbolism combine in a haunting image where the everyday streets and people of post-war Trastevere play their part in an allegorical vision of the Christian tradition of the seven deadly sins.

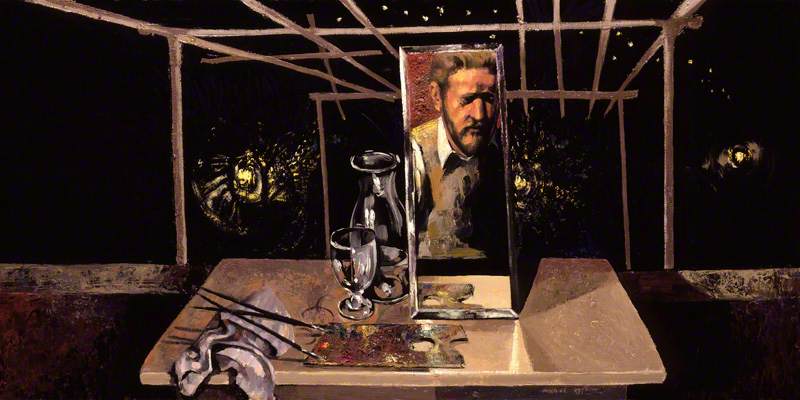

By now Ayrton was dissatisfied by the two-dimensionality of painted canvas. He moved out of London to the rambling Essex farmhouse that would be his home for the rest of his life, and set up his studio in the ancient barn opposite the house.

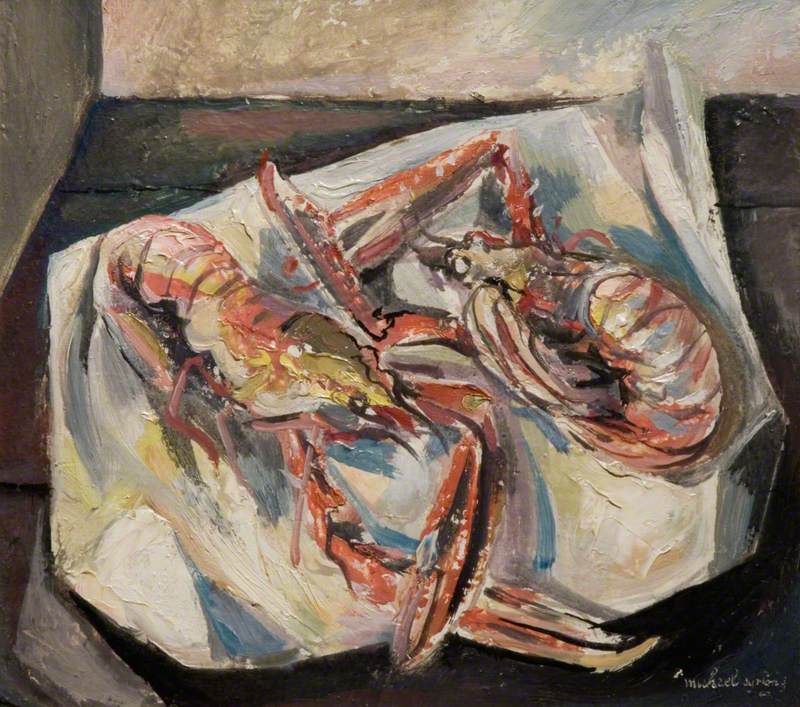

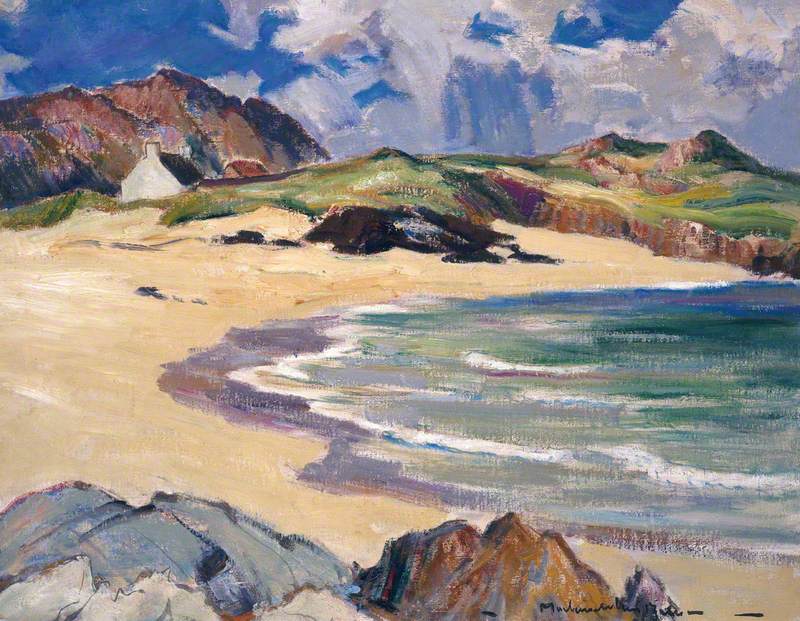

Still Life at Christmas

1953–1954

Michael Ayrton (1921–1975)

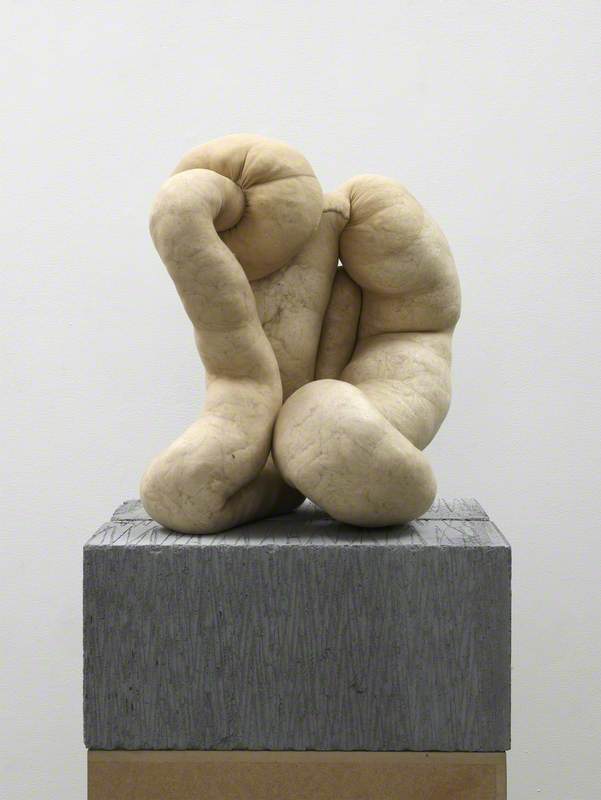

He painted a series of still lives exploring the relationship of objects in space and the produce of his new garden simultaneously, as in Still Life at Christmas (1954). After some months he began making sculpture, inspired by the work of Giovanni Pisano and encouraged by his neighbour, Henry Moore. The first figures he made were acrobats, performing feats of balance that in life could only be briefly sustained, made permanent by bronze.

Ayrton suffered all his life from an arthritic condition that restricted his movement and at times severely disabled him. The confident efficiency of his acrobats acted as a protest against his own state, a way of exploring it and a sublimation of the frustration it caused him.

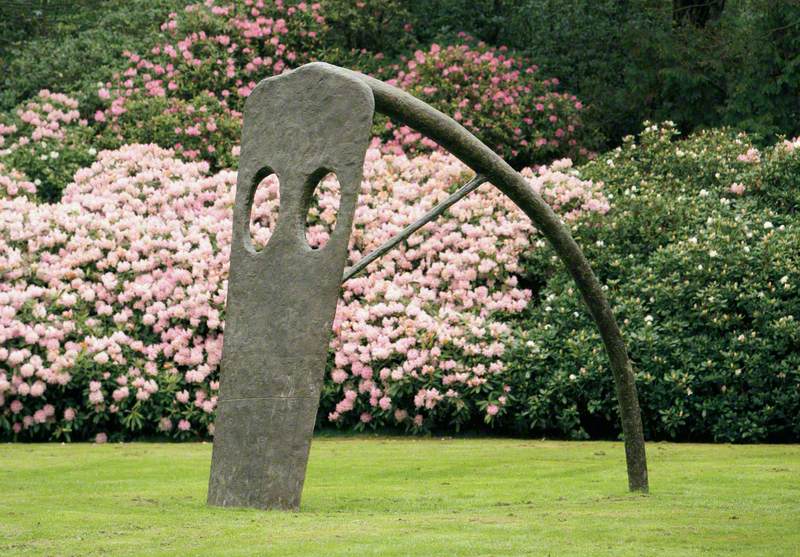

In 1956 he visited Cumae, north of the Bay of Naples. Here, according to legend, the master craftsman Daedalus landed after escaping from the Cretan labyrinth with his son Icarus, who died on the way when he flew too close to the sun and burned the wings his father had made. This myth and the associated story of the Minotaur imprisoned in the maze became Ayrton's major source of inspiration for the rest of his life.

He sculpted Icarus winged, Icarus III (1960), rising, and fallen, Icarus Transformed (1961–1963), finding in his story an urgent relevance to contemporary issues at a time when 'flight has released us into space and may yet kill not only Icarus but everybody else'. press photographs of astronauts undergoing training at high velocities influenced his images of Icarus transformed by his attack on the sun, Icarus in Flight (1960).

He also became increasingly involved with the bull-headed Minotaur, whom he saw as a tragic as well as a savage figure, trapped in his own body as surely as in the maze. Minotaur Waking (1972) gazes in perplexity at his own hand, unable to fathom its uses with his bull's brain – an all-too modern dilemma with which anybody cursing their computer can sympathise.

Ayrton began his involvement with the myths of Daedalus and Icarus, maze and Minotaur comparatively light-heartedly – he had not expected it to expand and engulf him as it did. In 1967 he published a novel, The Maze Maker, a fictional autobiography of Daedalus in which he approached the themes of his sculpture from another angle; as a result of its success he received a commission to design a full-scale masonry maze in the Catskill Mountains of New York. It survives to this day, with the Arkville Minotaur (1969) brooding at its centre. A second cast of this largest of Ayrton's Minotaurs lived for many years in Postman's Park, and now inhabits London Wall.

Yet even with the maze built, Ayrton realised that 'my imagery remains mazed because it cannot be otherwise', his mazes evolving beyond their originating myth to become an all-embracing metaphor for the human experience. He put people in mazes, Blade Maze Figure (1965), and mazes in people, Contained Maze (1966) – and experimented with the transformations of maze as mirror.

In Reflective Heads II (1971) two half heads aligned in opposite directions and each containing a smaller head facing and reflected in a bisecting sheet of polished bronze complete themselves as the sculpture is turned, offering an array of possible combinations of whole, half, fragmented and reflected heads and images.

Physical reflection suggests metaphysical meanings: Ayrton commented on the piece as an expression of 'my own feeling that everyone's personal maze is in his own brain.' The most exciting of these 'Reflectors' combine bronze with neutral density perspex, which reflects and also allows through vision: turning, images reflect and interpenetrate each other to create new forms and formal combinations.

Ayrton liked to describe himself as an 'image-maker', he also believed absolutely that without myth human existence becomes intolerable and that one of the purposes of being an artist is to find the appropriate images for the mythological in the particular time and place you happen to inhabit.

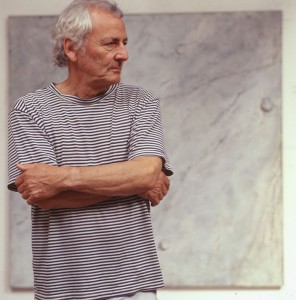

Ayrton in his studio, working on Reflective Heads II, 1971

The artist's preoccupations can be seen feeding into and enriching each other, revealing new facets of old ideas which in their turn lead on to the discovery and exploration of new ones; his works remain powerful because they are neither prescriptive nor limited in meaning but invite the viewer to explore and to imagine.

Justine Hopkins, step-granddaughter of Ayrton, writer and art historian

'A Singular Obsession – Celebrating the Centenary of Michael Ayrton' runs until 31st October 2021 at Fry Art Gallery, Saffron Walden