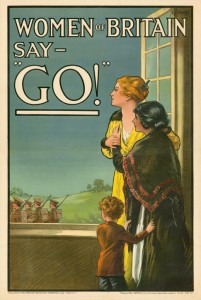

The First World War had a curious effect on the culture of monuments. While it pushed a number of artists to extraordinary efforts to realise something different, thus renewing the language of statuary and public sculpture as a whole, it also provoked so many thousands of run-of-the-mill memorials that it might be said to have put the brakes on modern sculpture.

If some memorials are notable for their apparently straightforward innocence, others by Eric Gill, Charles Sargeant Jagger, Eric Kennington, Gilbert Ledward, Edwin Lutyens and George Herbert Tyson Smith among others combine modern carving techniques and architectural frameworks to create sites of memory better suited to mourning.

Gill's war memorial at Leeds University, in the form of a sculptured frieze, was a notable indictment of the First World War, and those who had profited by it. In 1917, Michael Sadler, the Vice-Chancellor of the university, commissioned Gill to create the memorial.

Christ Driving the Moneychangers from the Temple

1921–1923

Eric Gill (1882–1940)

The sculptor proposed Christ expelling a group of moneychangers from the temple, yet he depicted the moneychangers in contemporary attire. The relocation of the memorial has changed that meaning, to a degree, but it is still a strikingly non-conventional memorial to those who had died.

The Second World War produced fewer notable examples of memorials, at least at the time. A new appetite for monuments only began to develop later on, most notably in subsequent generations.

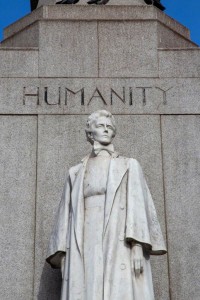

Jacob Epstein's gigantic war memorial for the TUC (Trades Union Congress) was only unveiled in 1958, but commemorates the dead of both wars.

War Memorial at Trade Union Congress, Great Russell Street

1950s, sculpture by Jacob Epstein (1880–1959)

Its subject is conventional enough – a pietà group – but the treatment and scale take it to another level.

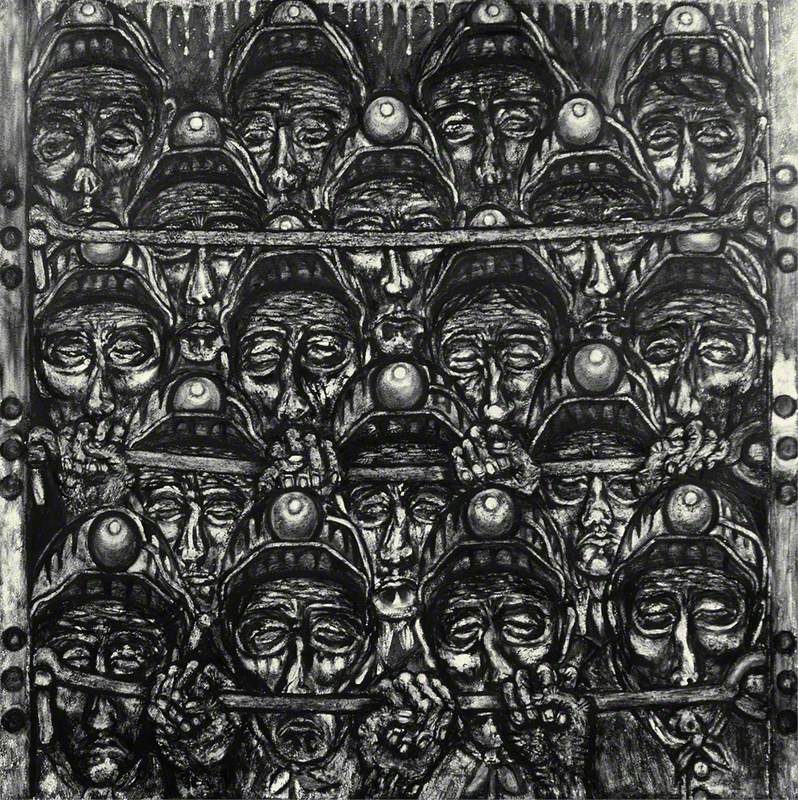

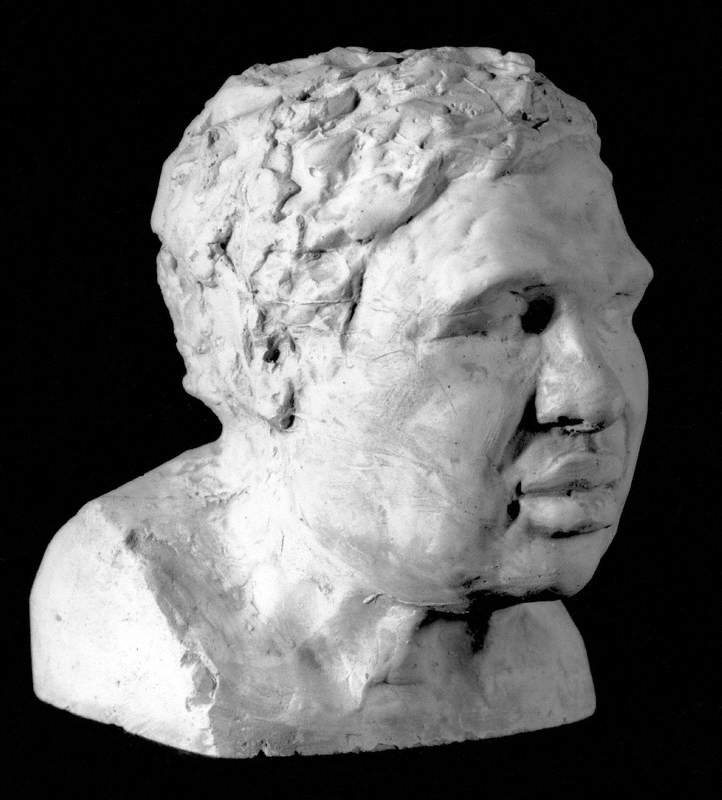

Eduardo Paolozzi's memorial to the dead of Monte Cassino only emerged in the 1990s, despite the artist's close experience of both the place and of wartime loss.

Manuscript of Monte Cassino

1990–1991

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005) and Raimund Kittl Foundry

The so-called 'Malayan Emergency' (1948–1960) is little remembered in Britain, even by its other name, 'the 'Anti-British National Liberation War'. A forgotten war emerges through a better-known memorial, that made by Barbara Hepworth to commemorate her son, Paul, who died in 1953 when his plane came down near Bangkok.

British dame Barbara Hepworth (1903/75) studied with Henry Moore.

— (@WomenArtists1) August 19, 2016

'Madonna and child' sculpture pic.twitter.com/Jz22qLM265

The Madonna and child is a traditional, essentially backward-looking, response from an artist who elsewhere sought to create new forms of memorial. A particularly relevant example would be her Single Form, ultimately dedicated to the UN Secretary-General shot down over the Congo.

The end of empire is a topic little associated with sculpture, but is there to be discovered.

Another anti-colonial war of the period, that fought in Algeria against the French, is evoked in a curiously ambiguous sculpture by Hubert Dalwood.

O.A.S. Assassins (1962), now in Tate's collection, refers both to the French Republic and to the right-wing group opposed to Charles de Gaulle's decolonising effort.

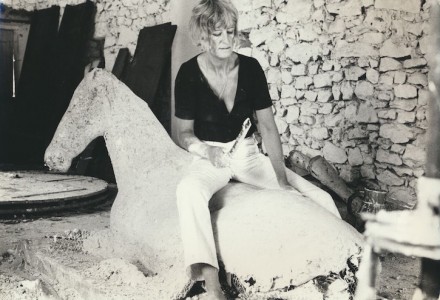

The recourse to traditional Christian motifs, as seen in Hepworth's madonna, was much more established as a strategy by Elisabeth Frink, whose crucifixions featured in churches in Belfast, Liverpool and London. Frink's figurative vocabulary was better suited than Hepworth's to a new rendering of bodily pain.

Another sculptor who has made a surprisingly successful entry into this minefield is Alison Wilding, whose font and fountains for the United Reformed Church in Bloomsbury's Regent's Square are entirely consonant with her existing vocabulary of forms.

Lumen United Reform Church on Tavistock Place, Bloomsbury.

— TheisandKhan (@TheisandKhan) September 21, 2019

The Sacred Space is a conical room lit by a single source of light 11m above the floor.

Lumen was awarded the @RIBA_London Award 2009.

It was a pleasure to work with @ModusOpArt & artists @rona_smith & Alison Wilding. pic.twitter.com/OGVqwaTnVB

This challenge – to mix modern sculpture with specific commemoration – has been a leitmotif of the last half-century.

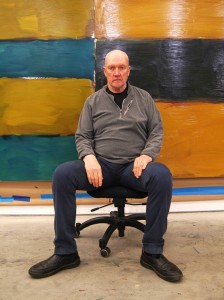

Already in 1944 Henry Moore had found a way, in his memorial to Christopher Martin, convincingly to marry his own language with that of dignified public respect. Using his reclining female form, Moore nonetheless made reference to archaic figures of funeral commemoration, as well as to more modern monumentality.

Nice light on Henry Moore's Memorial Figure this morning here @Dartington! You can see this sculpture for free at any time when you visit the gardens here. #nofilter https://t.co/fiIt9Ny8js pic.twitter.com/731XvNohD6

— Dartington Arts (@DartingtonArts) January 3, 2020

The female figure who is still reclining at Dartington Hall not only acknowledges its founder, but also a long lineage of figures which connote, at the same time, life and death. Moore was astute enough not to depict Martin, but instead tapped into an almost subliminal source of memorial figures, at once more anonymous but also more memorable.

The link between gardens and commemoration, notably (but not exclusively) in the form of graveyards, is interestingly connoted by Ian Hamilton Finlay.

The 'Grove above Lochan Eck' at Little Sparta

Garden designed by Ian Hamilton Finlay and Sue Finlay, Dunsyre, Scotland

The garden he created with his wife, Sue Finlay, at Little Sparta, Dunsyre in Scotland can be seen as a memorial in itself, especially after the artist's death. A more public example can be found in Hyde Park, where Finlay's Serpentine commission, dedicated to Princess Diana, is often overlooked.

Memorial to Diana, Princess of Wales

1997, by Ian Hamilton Finlay, Peter Coates and Andrew Whittle

While other nearby memorials to Diana have received more coverage in the press, Finlay's installation is a good example of the way the artist created sites of sculpture by appropriately combining words, forms and the cultivation of nature. In this he was prescient, and many of the better modern memorials have followed an example, which itself draws on Classical and Romantic tradition.

Penelope Curtis, curator and art historian