Susie MacMurray's figurative sculpture Medusa was the welcoming artwork at Masterpiece Fair in 2019. The striking sculpture has a copper body leading to a skirt of snakes, that appears to have frozen mid-motion at the base of the figure. It was so evocative that the mythological subject matter was easily deducible. Yet, instead of the universal image of a grotesque, gorgon's head, MacMurray's Medusa seems to take on a strong yet empathetic stance on the legend.

Medusa

2014, handmade chainmail of copper wire by Susie MacMurray (b.1959)

MacMurray hasn't always been an artist. She began her career as a musician and played in a symphony orchestra. Later on, spending time with her young children gave her leave to consider a different professional future. Once her children were old enough, MacMurray decided to enrol at art school, where she graduated with an MA in Fine Art in 2001.

Describing the experience of becoming an artist as 'like walking through a door and into a box of sweets', MacMurray relished the opportunity to follow her musings and investigate her own questions.

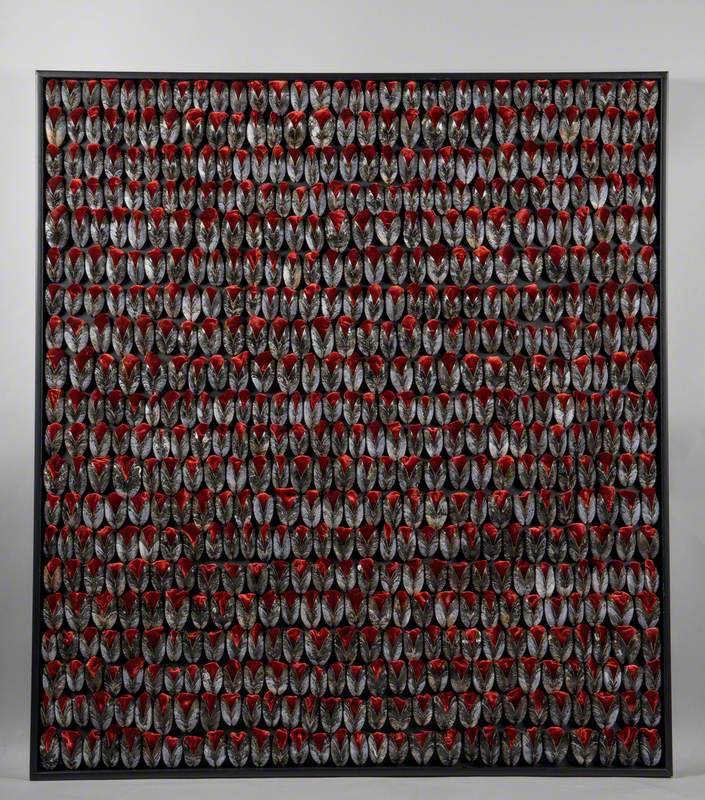

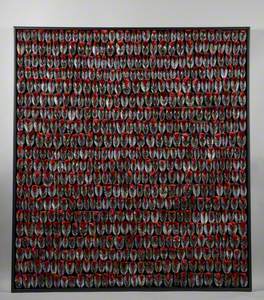

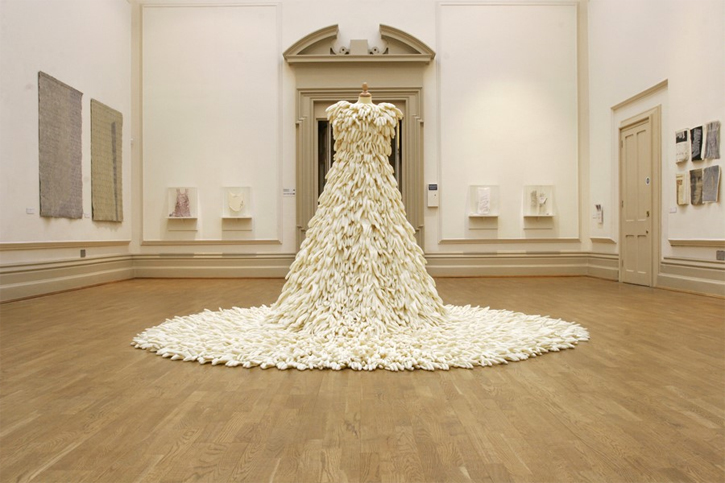

A Mixture of Frailties

2004, 1,400 household gloves turned inside out & calico by Susie MacMurray (b.1959)

Now, with an upcoming solo exhibition at the Pangolin Gallery on 20th October 2020, MacMurray will be showcasing more of her work with a wider audience. I spoke to MacMurray for Art UK to learn more about her artistic process, as well as her research and the inspiration behind her Masterpiece showcase.

Patricia Yaker Ekall: How was your Medusa created, and what inspired the angle you took?

Susie MacMurray: Medusa is an archetypal figure and a scapegoat – like the Bible's Eve. She represents the place where we put all the nasty stuff we don't want to think about; we just blame someone. Once you start looking at her story, you see that, like all Greek myths, there are different versions.

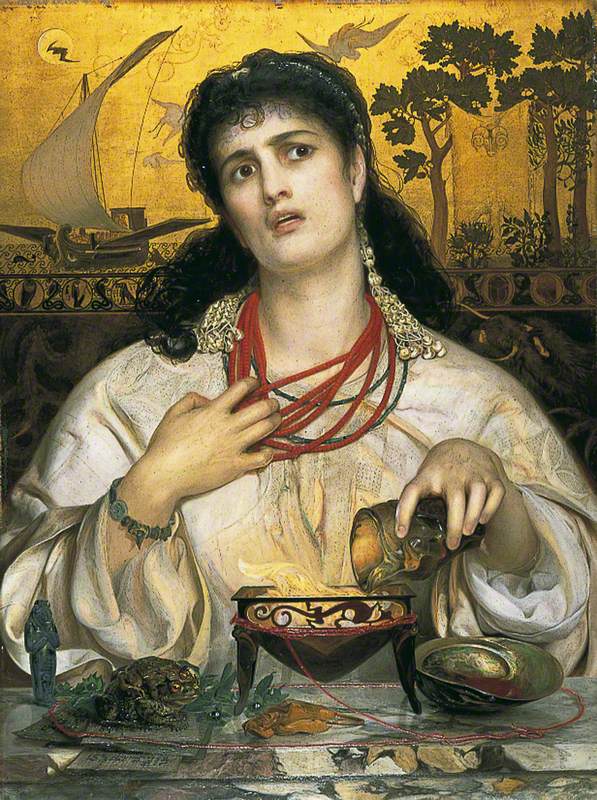

But I was inspired by Hélène Cixous' book called The Laugh of Medusa, where she says that Caravaggio's Medusa is not screaming, but rather revelling in her sexuality. I think Medusa's story represents the castration of female power. I mean, she's banished for being raped and then murdered.

Medusa

1595–1598, oil on canvas by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610)

In 2012, I had been thinking about Medusa when I heard about the Rotherham grooming scandal, in which children in care homes had been groomed for sex. I thought about what the lives of victims are like afterwards. They, too, are scapegoats because victims can be looked at as tarnished. That made me think: this goes all the way back.

I also referenced how, in the myth of Medusa, the blood from her head dripped into the sea as Perseus carried it home. It is said that is how corals from the Red Sea came to be. That's also why I chose copper: for its redness. It's untreated copper, so if you stood her outside, she would tarnish: a reference to the idea that she's a 'tarnished' woman.

Medusa

2014, handmade chainmail of copper wire by Susie MacMurray (b.1959)

The history of sculpture is very masculine. Casting in bronze is considered heroic and it's quite phallic in size and height: it's usually rigid, stiff and hard. I was very interested in subverting that and creating a sculpture that is metal but incredibly flexible.

The base [of Medusa] is entirely sinuous: you can arrange those snakes any way you like. It's the most tactile and sensual thing to handle, because they fall about in your hands. This symbiosis between strength and flexibility demonstrates an ability to look in all directions.

Patricia: What was the feedback on the sculpture while it was on display at Masterpiece? And how do people respond to your work in general?

Susie: It depends on the work. I do tend to get people telling me how they felt, which is lovely. I don't like the idea of excluding a whole group of people from being able to understand my work. Of course, if you have to write reams of text in order for people to access the work in any way, then you have to ask yourself: is this piece actually functioning? Who's it for?

Gladrags

2002, 10,000 fuchsia pink balloons by Susie MacMurray (b.1959)

Maybe coming from my performative background, I want people to have an emotional connection to the work. That's why I feel very strongly that you have to see art physically: there's only so much you can do digitally or on the page. Your body has to experience being in relation to that artwork, particularly sculptures and installations. You have to move through it and around it and have that relationship with it. That's what my art is for: it's a physical artform. Like posing a question to people. They don't necessarily know what the answer is, but they certainly understand the question. I've had absolutely amazing letters from people; I've had people in tears – which is extraordinary. It's quite a privilege to feel your work has resonated with someone.

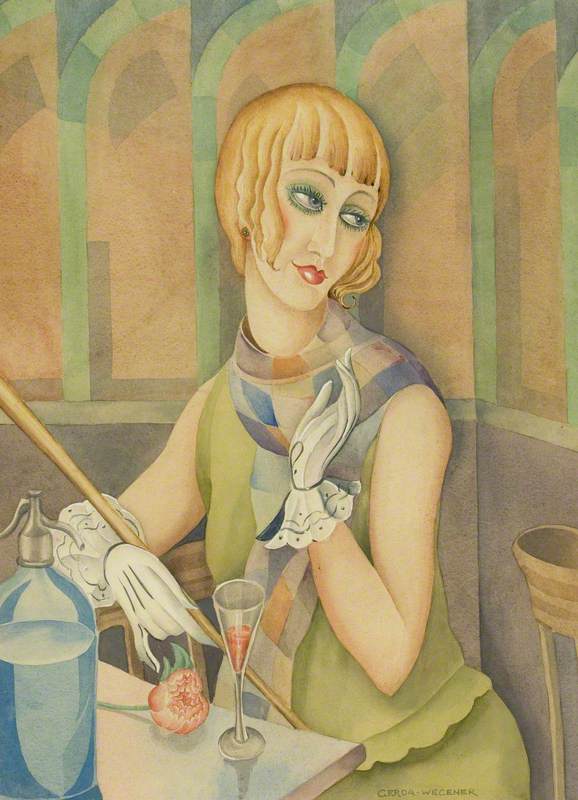

Pandora

2016, LED lightbox within doorframe & .50 cal. Browning machine gun bullets by Susie MacMurray (b.1959)

Patricia: Medusa presents a feminist subversion of the male gaze and narrative. Is this typical of your work?

Susie: First and foremost, when I make figurative sculptures, they're about my questioning of who I am. But you can't avoid engaging with the whole of art history because the gaze is there, isn't it? It's not that I set out to make a piece of work that's going to challenge the male gaze, but by what I'm thinking about and what I'm questioning, hopefully, it does. Also, when it comes to feminism, I am ambivalent about my own courage.

I am very good at talking about it and have very strong feelings about feminism but – would I put my money where my mouth is? Or can I just go on shouting at other people about what they should be doing? There's a sort of perennial ambivalence there; it's not very difficult until you're actually faced with a situation and have to stand up for what you believe in, at risk to yourself.

So, a lot of my work is about that; it's about doubt and uncertainty, ambivalence and the sort of ephemeral nature of things. It's also about loss and passing and time going by and all of those things – basically the human condition!

Patricia: What's the most important lesson you've learned so far as an artist that you could pass on to early-career creatives?

Susie: I think it's about integrity. Being true to your questions and what your intentions are. The artworld is tricky in that it's this monetised, commercial success-driven thing but you've also got the artist and the practice, which is very pure. It's a very strange mix that never settles. So, if you try and make art that sits with the zeitgeist, you're always going to be one step behind.

One of my art school tutors gave me some very wise advice in saying: 'you are who you are, and that may or may not be fashionable when you come out [of art school] … Stay true to yourself.' In art school it was all about the YBAs, and by my graduation show site-specific installation was totally out of fashion.

Pandora

2016, LED lightbox within doorframe & .50 cal. Browning machine gun bullets by Susie MacMurray (b.1959)

But I couldn't create work that wasn't me. So, you have to resist calculating what might work in the industry and stay true to your own way of operating.

Patricia: But isn't that scary, since it's so difficult to make a living from art?

Susie: Yes! You have to be prepared to accept the fact that you may never make a living out of it. But if you conform you'll always be behind and probably won't make it anyway. And then what will you end up with? A feeling of dissatisfaction. That's not why you make art. Art is too hard.

Susie MacMurray

In the long run, the compromises are not worth it. To choose not to do what might be advantageous is a difficult ongoing choice every artist has to make. Integrity.

Susie MacMurray's solo exhibition starts on 20th October 2020, at the Pangolin Gallery in London. The artist's other works can be found at www.susie-macmurray.co.uk or follow her on Instagram @susiemacmurray.

Patricia Yaker Ekall, journalist