The Victoria Art Gallery in Bath holds a large portrait by John Sanders (1750–1825) of a woman in a shadowy interior. She faces the viewer, and her walking stick, muff and straw hat suggest that she is about to go out for a walk.

Her name was Mrs Mary Jeffrey (1728–1808) – before that, she was Mrs Hayley, before that Mrs Storke, before that Miss Wilkes. By 1794, when Sanders painted her, she was living in Bath. As the gallery notes, her life there was 'far from quiet', which can also be said of her whole life. However, she has been overshadowed by her brother, the radical politician and journalist John Wilkes (1725–1797), who was a fierce champion of liberty. Like him, she was smart and witty – and her story is every bit as eventful.

Wilkes was born in Clerkenwell in 1728, the daughter of Israel Wilkes II, a malt distiller, and Sarah Heaton, a tanner's daughter. Despite the family's cosmopolitan lifestyle, they descended from a Shropshire farmer, Edward Wilkes (d.1699), the son of Richard Wilkes (d.1655), a yeoman of Aldersley near Wolverhampton; before this, the Wilkeses had lived in Willenhall. These humbler origins were obscured after Edward Wilkes's son Israel moved down to Southwark to apprentice as a distiller in 1681; his son Israel II, Mary's father, increased the family's fortune.

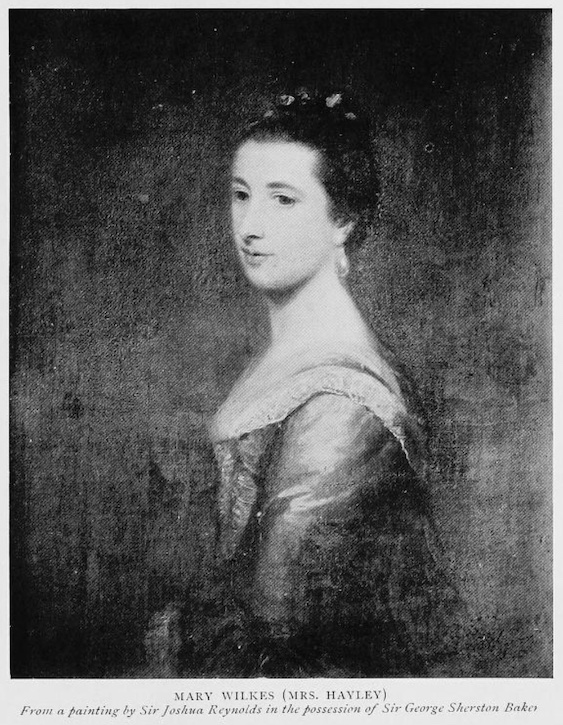

Image credit: from Horace Bleackley's 'Life of John Wilkes' (1917); courtesy the author

Mary Wilkes (Mrs Hayley)

print after Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Mary's liberal attitudes and 'disregard for propriety' became clear early on. A writer in 1818 remarked that 'She was exceedingly well informed, had read a great deal, possessed a fine taste […] and unfortunately like her brother [John], she never permitted any ideas of Religion, or even of delicacy, to impose a restraint upon her observations'.

An oft-cited anecdote is that she regularly attended trials at the Old Bailey, where a seat was reserved for her. The same author wrote: 'When the discussion of the trial was of such a nature that decorum, and indeed the judges themselves desired women to withdraw, she never stirred from her place, but persisted in remaining to hear the whole with the most unmoved and unblushing earnestness of attention.'

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Mary Hayley (née Wilkes)

published 1821 (1763), mezzotint by Samuel William Reynolds (1773–1835) after Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Wilkes's connections with the United States first came about through her marriage, in 1752, to Samuel Storke, a merchant who traded to New England; he died a year later. Soon after, in 1754, Wilkes wed her second husband, George Hayley. A former clerk in her first husband's office, he was now a merchant with commercial ties to Massachusetts – he even conducted business with John Hancock, a future Founding Father of the United States. Like the Wilkeses, Hayley supported the American colonies' fight for independence; the American writer Arthur H. Cash described him as 'a docile follower' of John Wilkes. He was later MP for the City of London in 1774.

The year 1759 saw the birth of Mary and George's only child, Dinah, with whom Mary would have a strained relationship.

Image credit: from Horace Bleackley's 'Life of John Wilkes' (1917); courtesy the author

Dinah Hayley, later Lady Baker

miniature by an unknown artist

George eventually died in 1781, and Wilkes was a widow once more. She continued her husband's business in London, but as she was also owed money from merchants over in Boston, she decided to go there and collect the debts herself. In May 1784, Boston newspapers heralded the arrival of 'The Sister of the celebrated John Wilkes', aboard an American ship from the Revolutionary War which Mary had cannily purchased to demonstrate where her sympathies lay.

Boston had seen much conflict before and during the Revolution, such as the massacre of 1770, when British soldiers opened fire on American civilians during a skirmish.

Image credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, public domain

The Boston Massacre

1770, hand-coloured engraving and etching, engraved and printed by Paul Revere Jr. (1734–1818) after Henry Pelham (1749–1806)

Some historians have compared this incident with the St George's Field Massacre of 1768, when British soldiers shot at a crowd of people demonstrating against John Wilkes's detainment in the King's Bench prison, killing several protestors. By 1784, Boston was a calmer city. Mary Wilkes swiftly established herself there as a businesswoman, including in the whaling industry.

Wilkes married her third husband, Patrick Jeffrey, in Boston in 1786. Rumours circulated that Jeffrey only married Wilkes for her money, which, because of the laws of the time, automatically passed to him. The marriage turned sour, and in 1792 Wilkes ceased her operations and returned to England alone. She spent the rest of her life in Bath, where she was known as Madam Jeffrey. She was painted by John Sanders in the mid-1790s, while the painter was also living there.

Wilkes had a friendly relationship with her brother. In historian Peter D. G. Thomas's words, 'Of all John's siblings his only source of strength was his formidable sister Mary'; for Cash, she was John's 'valuable ally'. When her brother returned from exile in France in 1768, it was at her house in Whitechapel that he first took refuge. He had been mired in legal troubles for several years. His article critiquing George III (1738–1820) and Prime Minister George Grenville (1712–1770), published in his newspaper The North Briton in 1763, had landed him briefly in prison for libel and led to his flight to Paris.

On John's return to England in 1768, he was imprisoned in the King's Bench for his outstanding conviction, although this did not prevent him from being elected MP for Middlesex shortly before. A portrait of him with John Glynn (1722–1799), a lawyer, and the reverend and politician John Horne Tooke (1736–1812) was published as a print in February 1769, while John was behind bars.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

John Glynn, John Wilkes and John Horne Tooke (copy after an original of 1769)

Richard Houston (1721/1722–1775) (copy after)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonClearer in the print version is a female figure of Liberty in a picture on the wall above John; the mantra of 'Wilkes and Liberty' was inseparable from his name, together with the number '45' (referring to the North Briton).

William Hogarth's (1697–1764) caricature of him from 1763 transforms John into a devilish figure, partly by exaggerating his facial features (he was naturally cross-eyed, with a protruding jaw).

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

John Wilkes Esq.

1763, etching and engraving by William Hogarth (1697–1764)

As scholars have noted, Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) appropriated John's pose in Hogarth's print for his portrait of George III in 1771, evidently in an attempt to portray the king as a popular figure to rival the very popular John Wilkes.

Image credit: Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

George III (1738–1820)

1771, oil on canvas by Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

John's personal life was also troubled. He married Mary Meade in 1747, but the couple eventually separated. Their only child together was Mary, nicknamed Polly, to whom John was deeply attached. When he was elected Lord Mayor of London in 1774, he named Polly his Lady Mayoress, rather than his wife. Father and daughter sat for a portrait by Zoffany, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1782.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Mary Wilkes; John Wilkes exhibited 1782

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonThis informal likeness contrasts with Robert Edge Pine's (1730–1788) portrait of John as a statesman. A medallion of the seventeenth-century English rebel John Hampden (1595–1643), conspicuously placed in the corner, alludes to the radical ideals which John likely shared with his sister Mary. Besides sympathy with the American colonies, these included calls to end 'general warrants' (by which individuals could be arrested without being named) and for the freedom of the British press to publish verbatim records of parliamentary debates for public scrutiny, without fear of repercussions.

Mary Wilkes Storke Hayley Jeffrey died in Bath on 11th May 1808, and was soon forgotten by the public. Horace Bleackley, in his biography of her brother, dismissed her with a shower of epithets: 'remarkably plain', 'a self-assertive little shrew', 'a vitriolic young lady, brisk, bustling and shrewd'. John's other biographers have cast Mary as fiery and opinionated; Charles Chenevix Trench dubbed her 'a belligerent Wilkite' who staunchly defended her brother's views. Meanwhile, her enterprising spirit and business activities were glossed over. This article has hopefully redirected attention to this fascinating woman once again.

Robert Wilkes, independent art historian based in Juiz de Fora, Brazil

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Horace Bleackley, Life of John Wilkes, John Lane, 1917

John M. Bullard, The Rotches, The Cabinet Press, 1947, pp. 54–55, quoting the article about Mary Wilkes from the Boston Intelligencer (7 February 1818)

Arthur H. Cash, John Wilkes: The Scandalous Father of Civil Liberty, Yale University Press, 2006

Amanda Bowie Moniz, 'A Radical Shrew in America', in Commonplace: The Journal of Early American Life, 2008

Peter D. G. Thomas, John Wilkes: A Friend to Liberty, Oxford University Press, 1996

Charles Chenevix Trench, Portrait of a Patriot: A Biography of John Wilkes, William Blackwood & Sons, 1962

Charles Denby Wilkes, The Wilkes Chronology: An Historical and Genealogical Document, Klausfelder Société anonyme de l'imprimerie et lithographie, 1959

Audrey Williamson, Wilkes: 'A Friend to Liberty', E. P. Dutton, 1974