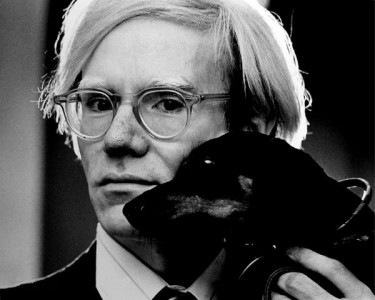

'I arrived in New York for the first time on the Fourth of July 1964. The following day I made my first telephone call, to the number listed under Andy Warhol in the phone book. A female voice answered "Andy Warhol". I was puzzled. It was eventually revealed that this was something called an Answering Service. I left a message to the effect that I was a student of Richard Hamilton's, and that Richard, who had met Andy Warhol at the Duchamp exhibition in Pasadena the previous year, had suggested I call. The next morning my phone rang for the first time. "This is Andy Warhol"; the voice, though never heard before, was unmistakably his. He invited me to "come by the Factory" that afternoon. "We're making a movie".'

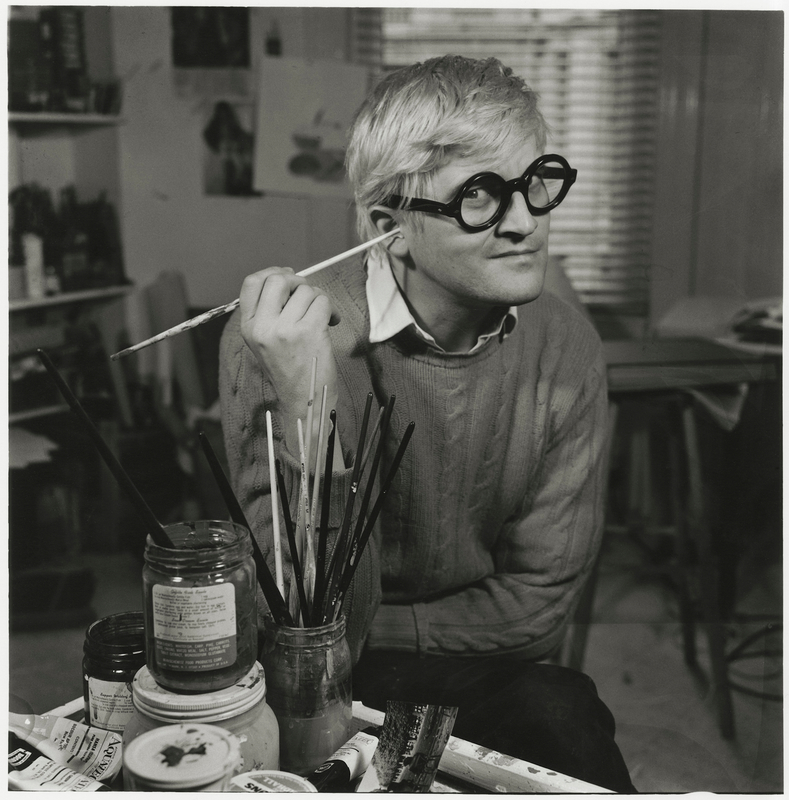

So wrote the English artist Mark Lancaster in 1989, in an article about his late friend Andy Warhol (i). As a 26-year-old student of Fine Art at the University of Newcastle – he studied there under Richard Hamilton between 1961 and 1965 – Lancaster's introduction to the New York art scene proved to be an exhilarating and defining experience.

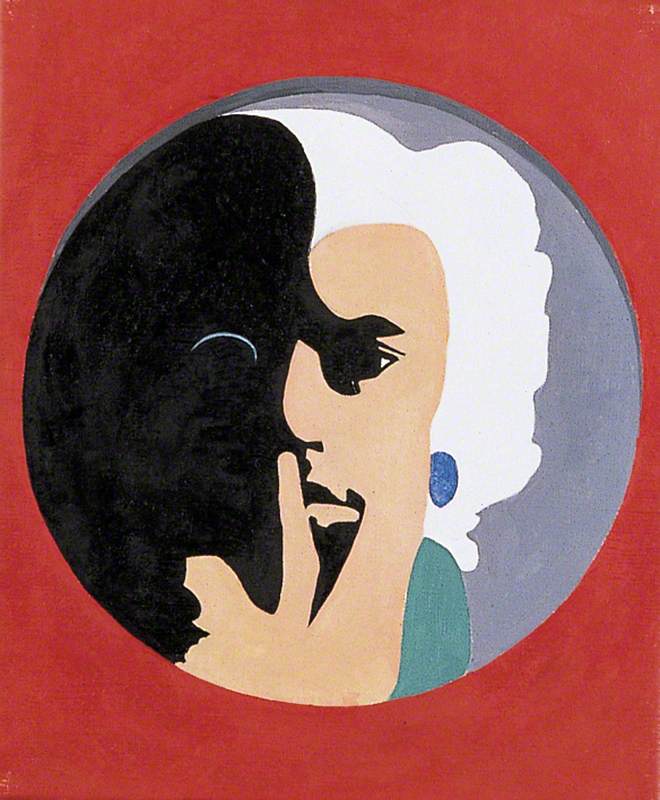

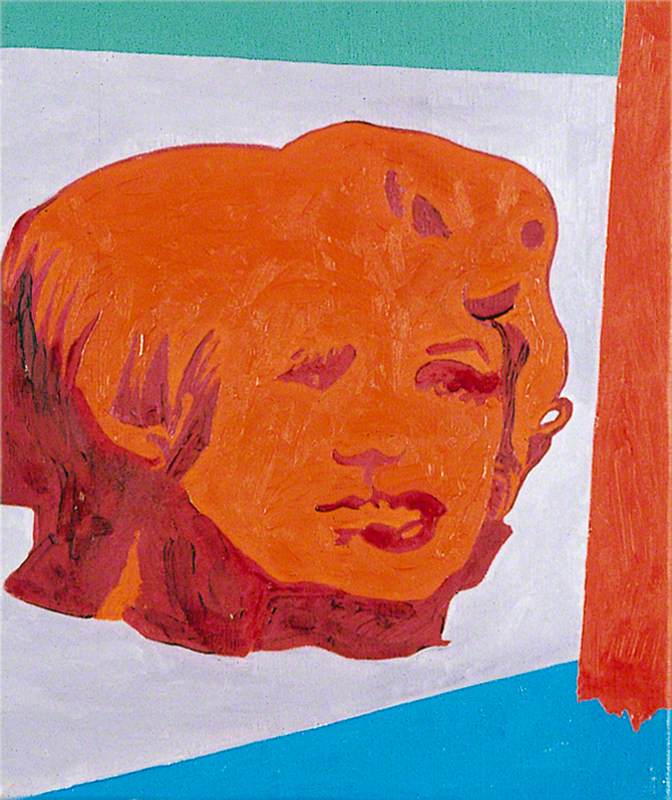

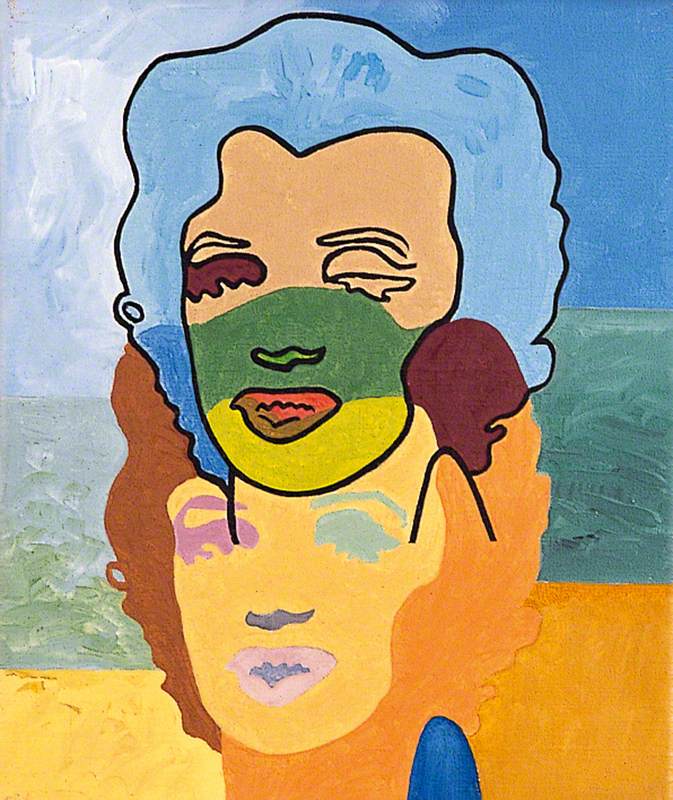

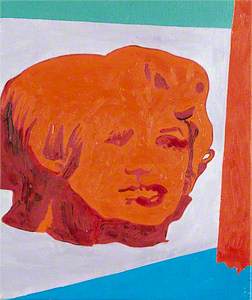

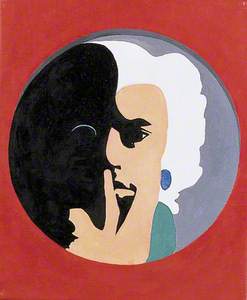

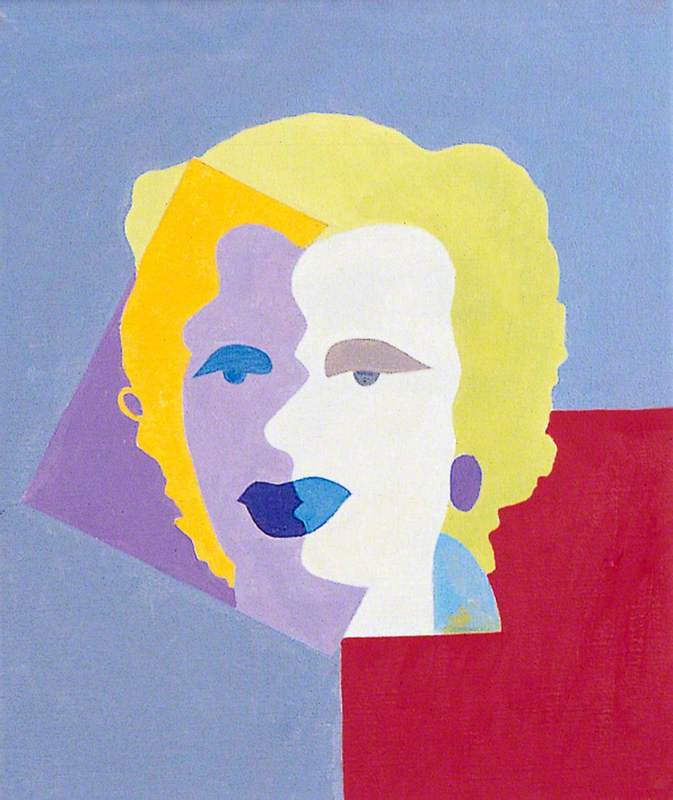

Post-Warhol Souvenir Marilyn (10–12 Nov. 1987)

1987

Mark Lancaster (1938–2021)

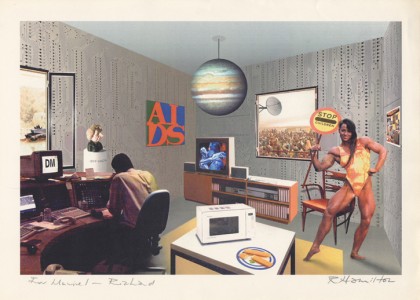

Within days of his arrival he was assisting Warhol in his studio, stretching silk-screened canvases for the artist's Flower and Most Wanted Men series, and became roped in to appear in two Warhol films, including Kiss, in which he and Gerard Malanga are seen locked mouth-to-mouth in a three-minute sequence. And crucially, Warhol introduced Lancaster to Henry Geldzhaler, curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art, who in turn introduced him to artists including Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, Ellsworth Kelly and Jasper Johns.

The distinctive body of work Lancaster left to us ... is remarkable in its invention and intelligence, and ripe for serious reappraisal.

Originally from Holmfirth in Yorkshire (setting of the Last of the Summer Wine television series), Lancaster was a dandyist mod and, by all accounts, an attractive, incredibly charismatic man. The first of Newcastle's art students to visit America, his return for the new term in September 1964 was greeted as that of an envoy bearing eagerly awaited reports from the white heat of contemporary New York art and culture. In Remake/Remodel – Michael Bracewell's book about the formation of the band Roxy Music – Lancaster's friend and fellow student of Fine Art at Newcastle, the singer Bryan Ferry, describes him as: 'the coolest of the cool... He was slightly older than the rest of us, and having his final [degree] show not long after I arrived at the University – really beautiful pictures...' (ii).

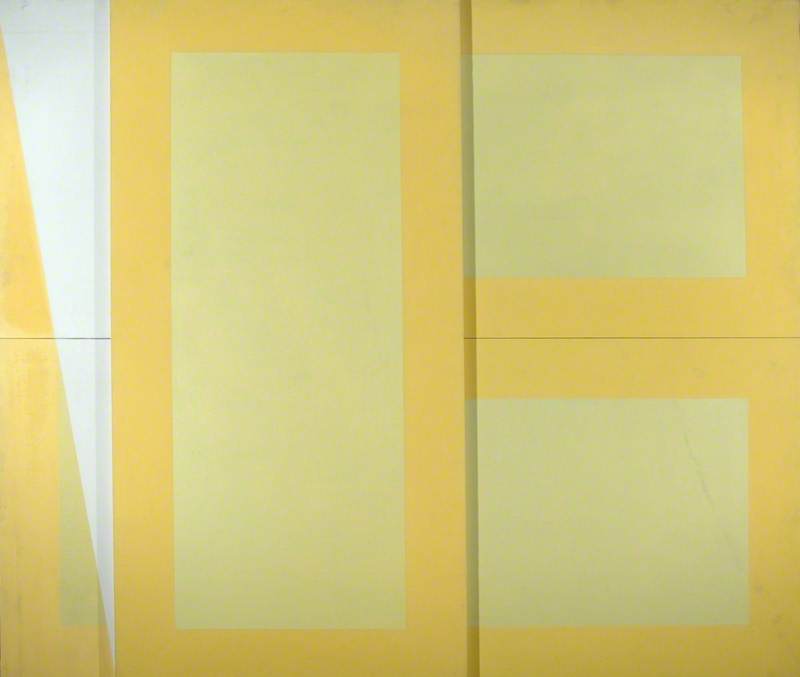

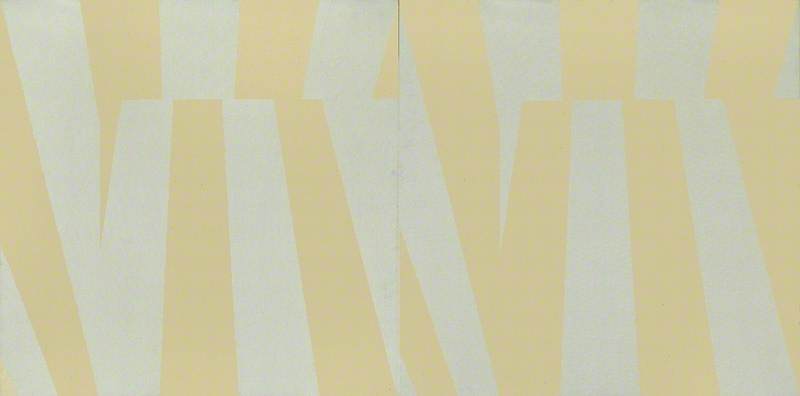

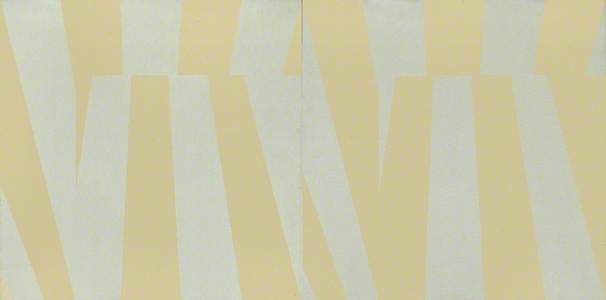

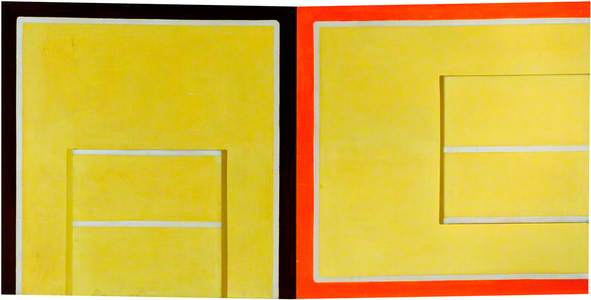

Lancaster had been working in a pop idiom before his New York visit, his work influenced and inspired by both Hamilton and Richard Smith. The pictures made on his return however were altogether more expansive in scale and ambition: abstract canvases based on American ephemera – things that presented him with a readymade compositional structure, such as a restaurant chain's printed paper napkins and placemats, or postcards showing more than one image. From this source material Lancaster invented arbitrary rules concerning colour and scale, from which to then manipulate the 'given'.

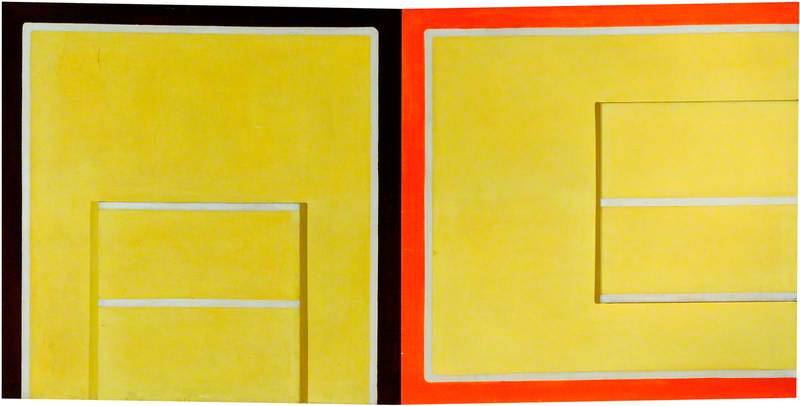

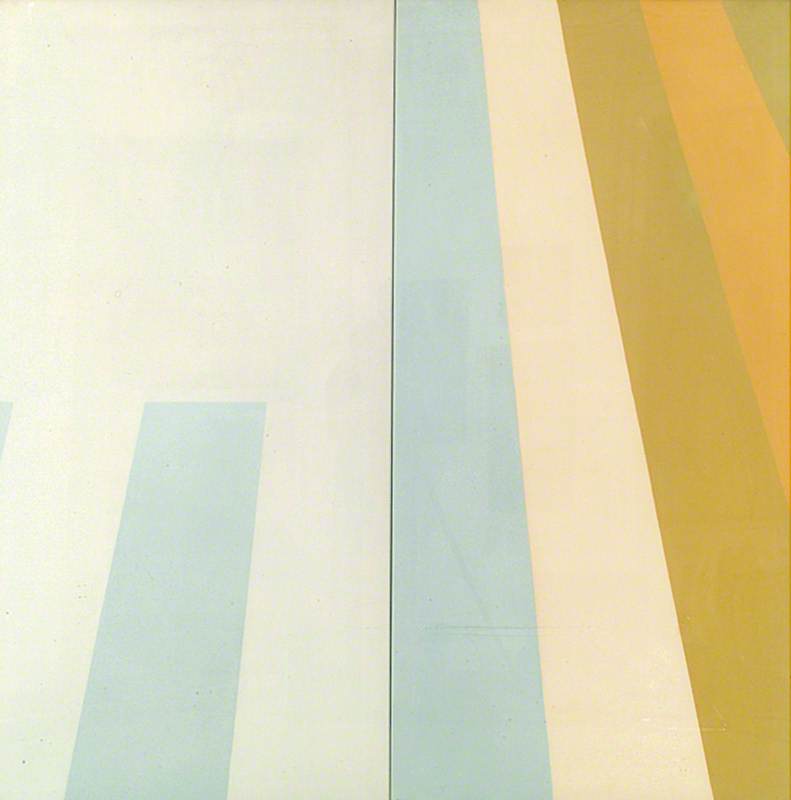

Among examples are the coolly austere Bloomingdale (1965), formed of four joined canvases, and the diptych First Spread (1966), in which the forms in each canvas are the same, but their colours reversed, positive to negative.

Soon after his graduation in 1965, Lancaster had a show with the Rowan Gallery in London, then, in the following year, four of his canvases – including First Spread – were included in the Whitechapel Gallery's 'New Generation' show, alongside work by twelve other young artists, amongst them his friends Roger Cook and Mario Dubsky. He continued to explore the formal concerns established after his American sojourn, in pictorial designs informed by a highly refined aesthetic sensibility.

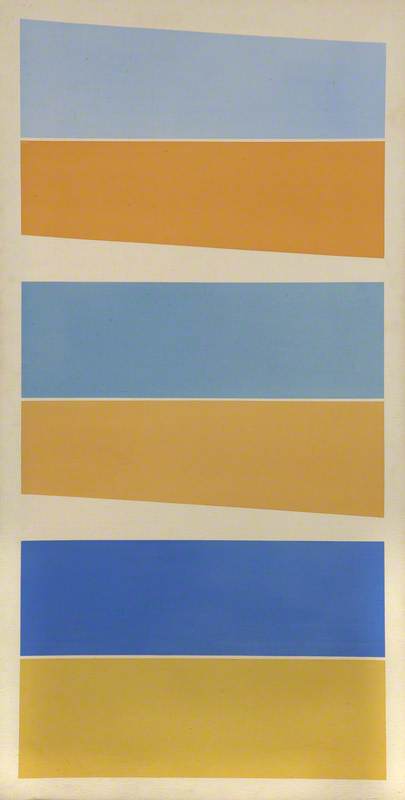

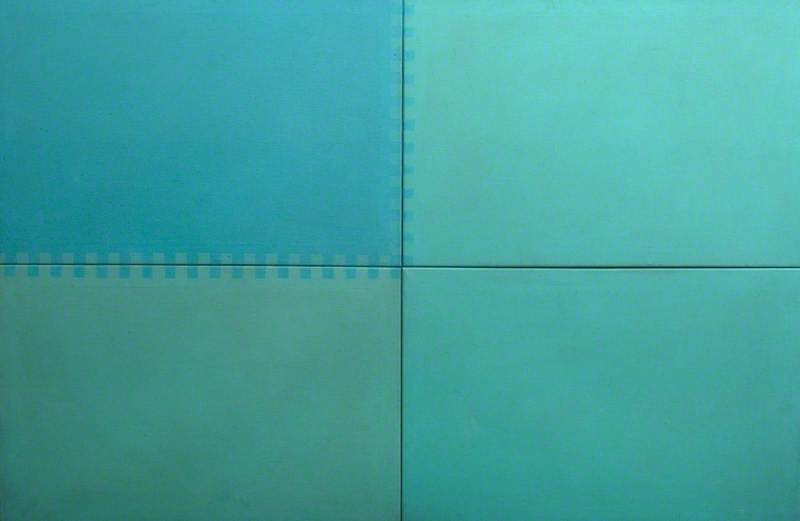

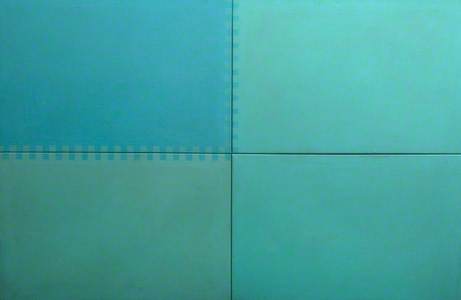

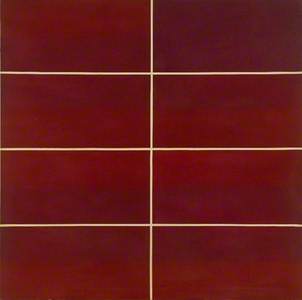

Zapruder (1967) is the first of a series of paintings, watercolours and lithographs of the same title and similar composition.

It is based on stills from an amateur film made by Abraham Zapruder in Dallas in November 1963, in which he captured the assassination of the 46-year-old President Kennedy. This footage was printed, frame-by-frame, in Life magazine – Lancaster professed himself struck by these images and their emotional content. Zapruder is formed of uniform rectangles set within a grid, its lines the width of the masking tape used to mark them out. In an intentional strategy of re-enactment, Lancaster remixed his green Liquitex paint from memory after each batch ran out, resulting in a sequence of nuanced variations, akin to those in filmed light and colour.

Whilst the work may appear coolly cerebral in its formal neutrality when considered against the stark psychological impact of Kennedy's murder, there is an underlying aspect to it, for as Lancaster stated in relation to his paintings more widely: 'the grid... presented itself to me as a way to make an abstract painting that was also packed with other emotional and hidden meanings.' Naturally he had learnt from Warhol the power of repetition and ostensible detachment.

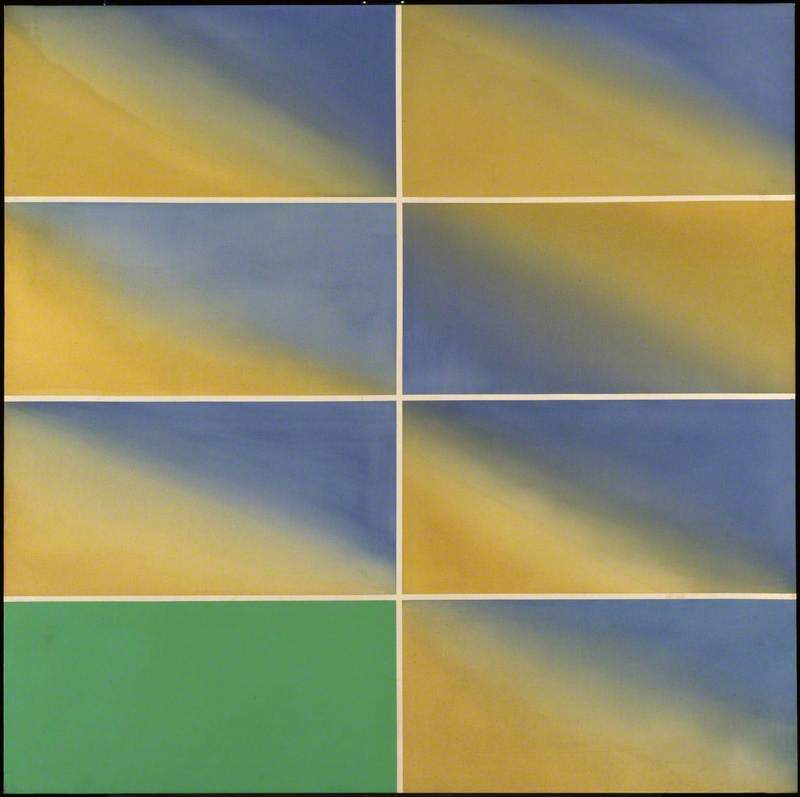

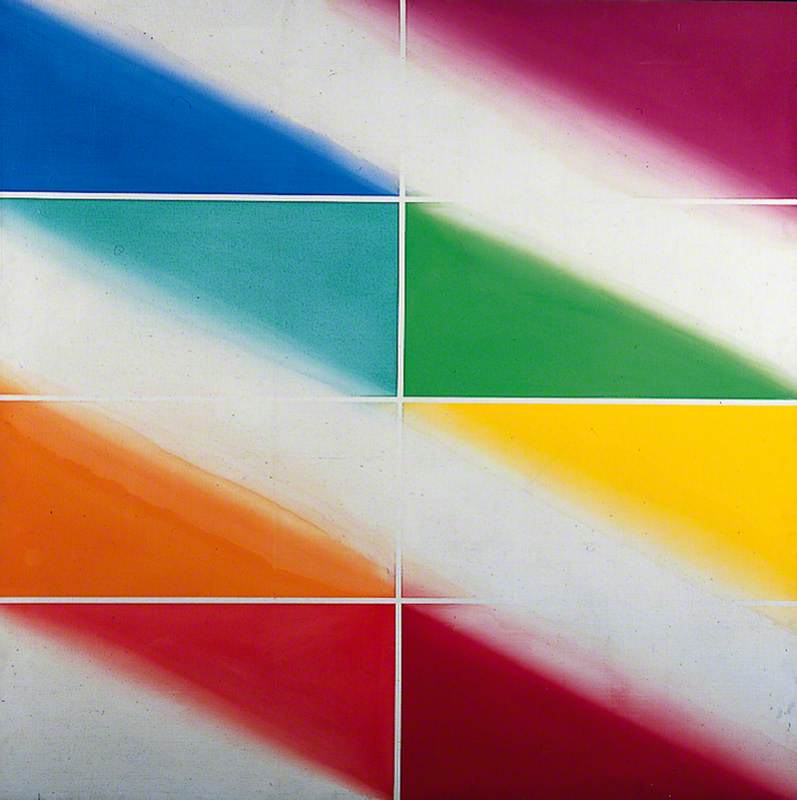

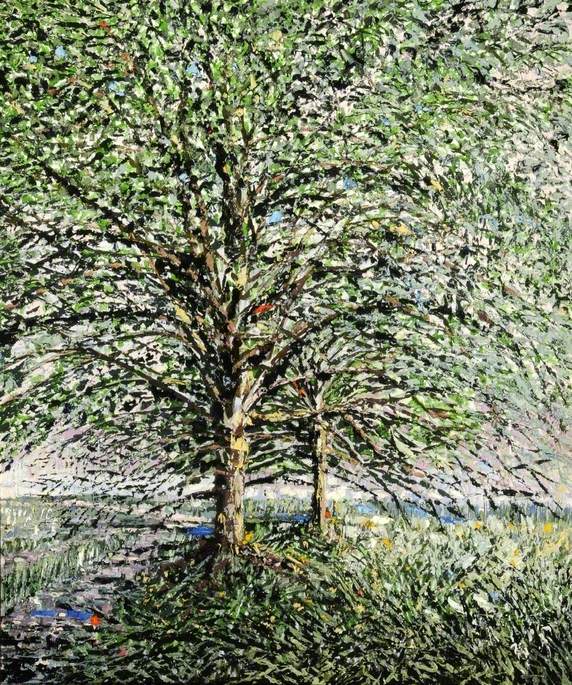

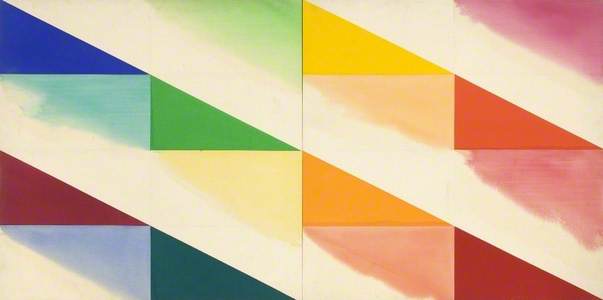

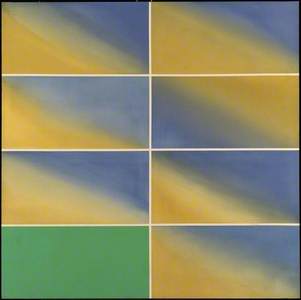

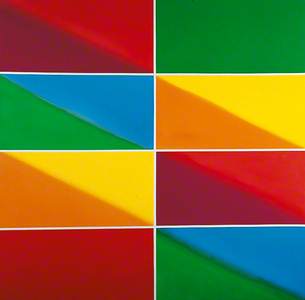

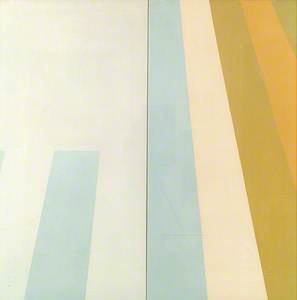

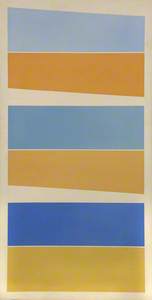

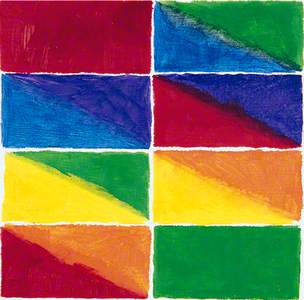

Invited to become the first Artist in Residence at King's College, Cambridge (1968–1970), Lancaster continued to explore the possibilities of the grid as a structural device. His palette and treatment became richer and more varied: see for instance Cambridge Eight (1968) and Cambridge July (1969), in which the rectilinear grid is partially camouflaged by dramatic diagonals, and the acrylic paint applied in dilute washes, their edges bleeding into the weave of the canvas.

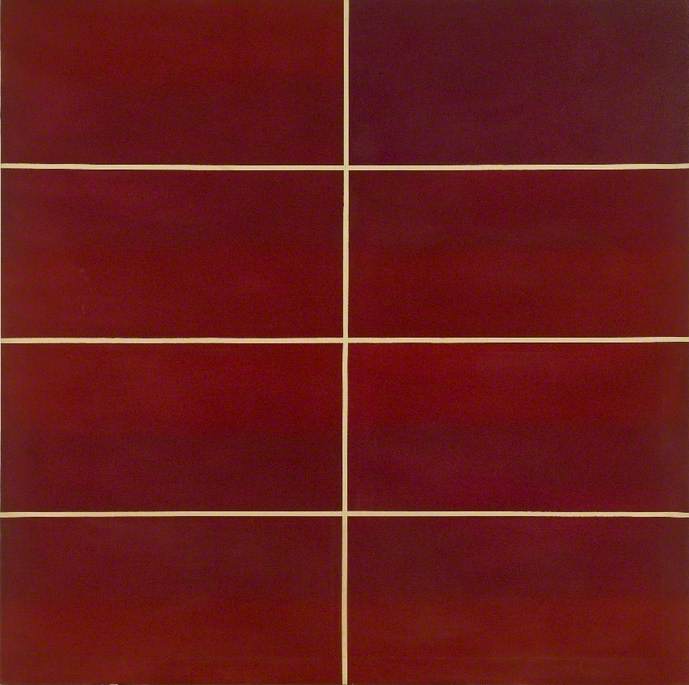

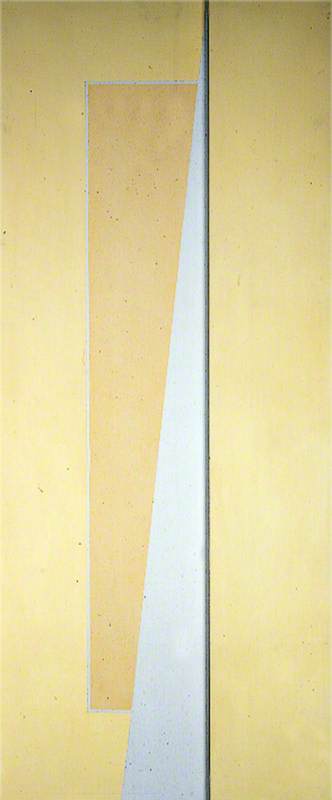

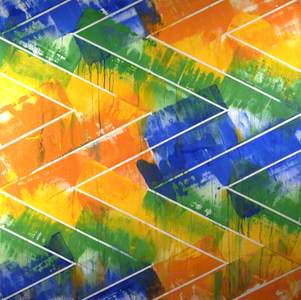

Gradually the paintings became more complex and openly expressive, more ambiguous spatially. Much of this came as a result of the artist's use of a squeegee with which to apply paint – an implement more usually associated with silkscreen printing – and the incidental smears and blotches that ensue from pressing it across the nub of the canvas. The technique allows also for a wider tonal range, resulting from both the amount of pigment and degree of pressure used when spreading it over the picture surface. This range is apparent in works such as the subtly dynamic King Study II (1970), a finely judged balance of gesture and restraint.

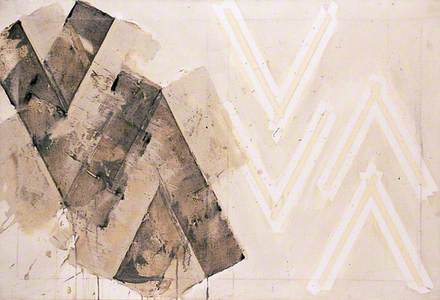

In 1970/1971 Lancaster made a series of paintings named after eighteenth- and nineteenth-century architects who had designed major buildings in Cambridge: George Frederick Bodley, William Wilkins and James Gibbs.

Texturally rich, their palette echoes the greys and browns one associates with building materials. By now the grid has exploded yet further, submerged in multi-directional layering. James Gibbs is especially impressive, made more complex and mysterious by overprinting a delicate mesh pattern across its surface.

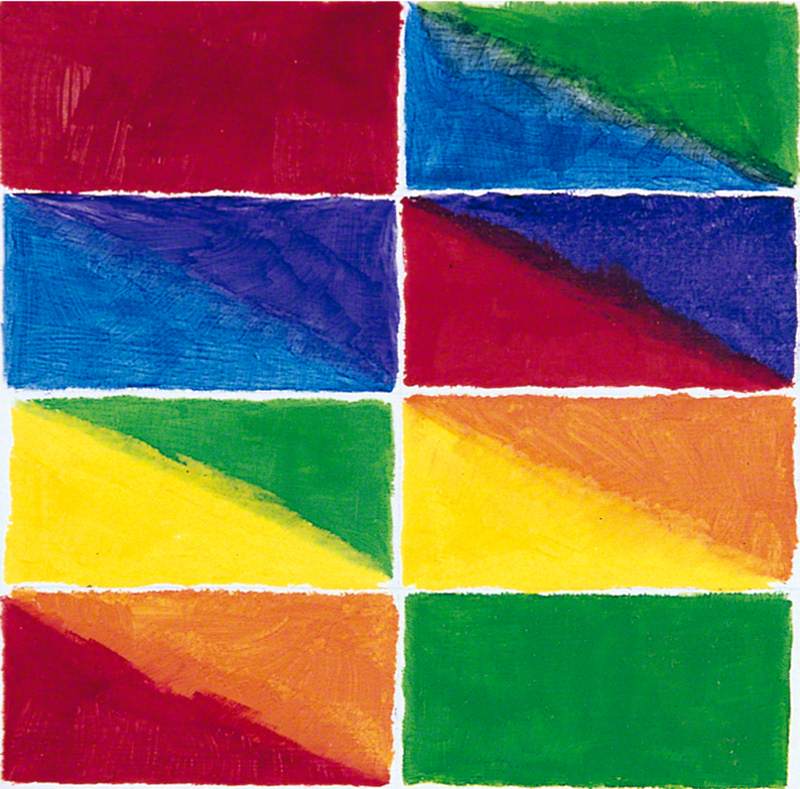

Whilst resident at Cambridge, Lancaster met the Bloomsbury painter Duncan Grant. He was fascinated by Bloomsbury, especially admiring of the painting and decorative work of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, which from the mid-1970s influenced the next stage of his development. Whilst continuing to structure his canvases by utilising a grid, his paint handling became altogether looser, his pictorial language iconographic rather than formal.

An example is Blue I (1974) which, in contrast to the highly controlled earlier paintings, repeats an abstracted motif transcribed in a series of twelve extemporisations, each with a different set of emphases, the bottom quartile of the sixteen-frame canvas containing nothing save for a shower of incidental drips and splotches of runny pigment.

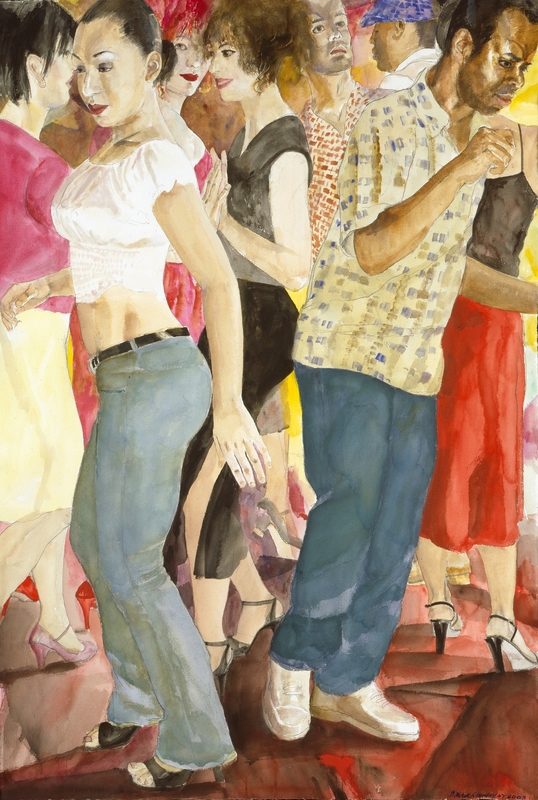

Lancaster returned to New York in 1972, where he showed with the Betty Parsons Gallery. He became secretary to Jasper Johns, with whom he developed a close friendship; the role of managing Johns' business affairs took up much of his time and continued for many years. He began also to work regularly with Merce Cunningham's dance company, as both costume and lighting designer, in a series of collaborations that continued well into the 1980s, bringing him into direct contact with the composer John Cage amongst other luminaries.

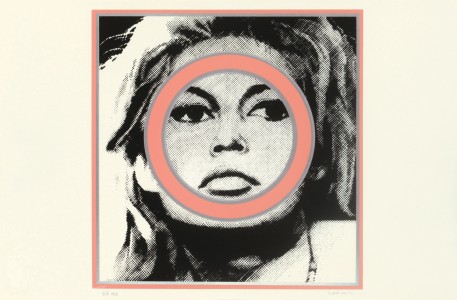

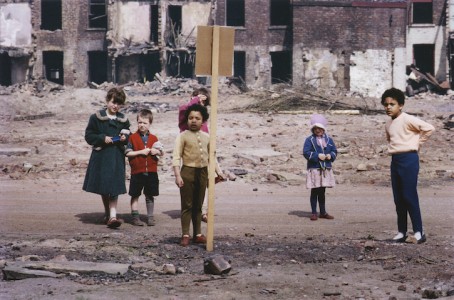

Lancaster is fairly well represented in British public collections – 29 of his paintings are documented on Art UK. They form two distinct categories: along with his abstract canvases are figurative works from a series of 180 paintings entitled Post Warhol Souvenirs, made in homage following the artist's death in 1987.

All the same size (30.5 x 25.4 cm), they combine images of Marilyn Monroe (based on Warhol's portraits) with representations of Warhol himself. They were shown at the Mayor Rowan Gallery in London in 1988, with another show of work two years later at the same gallery. After that Lancaster stopped painting. He and his partner, fellow artist David Bolger, were now living in Scotland, from where they moved to Miami, where Lancaster had a show of older work in the early 1990s, the last solo outing during his lifetime. According to Bolger, working for Jasper Johns: 'although a good thing in general, disrupted Mark's painting career in a way he couldn't fix.' So, now financially secure, he simply ceased production.

The distinctive body of work Lancaster left to us – including that made with Merce Cunningham – is remarkable in its invention and intelligence, and ripe for serious reappraisal. There is also a great deal that might be written about his life, for he inhabited a number of fascinating, often intersecting social spheres. Long open about his homosexuality, his milieu was largely, though not exclusively, gay. In England, his circle included the artists David Hockney, Keith Milow, Patrick Procktor and Stephen Buckley, and the writers David Plante and Nikos Stangos. Among the many other cultural figures he crossed paths with – and it's a long list – were the writers Christopher Isherwood, and E. M. Forster, who he met and befriended during his Cambridge residency. Worlds within worlds within worlds...

Ian Massey, art historian, writer and curator

With many thanks to David Bolger and Michael Bracewell.

Ian Massey's book Queer St Ives and Other Stories will be published by Ridinghouse in 2022.

(i) Mark Lancaster, 'Andy Warhol remembered' in The Burlington Magazine, March 1989, pp.198–202

(ii) Michael Bracewell, Remake/Remodel, Faber & Faber, 2007, p.84