Through her long career, Scottish painter Lys Hansen has covered the whole range of emotional extremes: everything from motherhood's joy to the despair of war.

Her works are nowadays held overseas by collections in Germany and Denmark, a country to which she has family links. Hansen is also represented by a few of her home nation's public collections, where, during the 1980s, Hansen was instrumental in fighting for space for women artists.

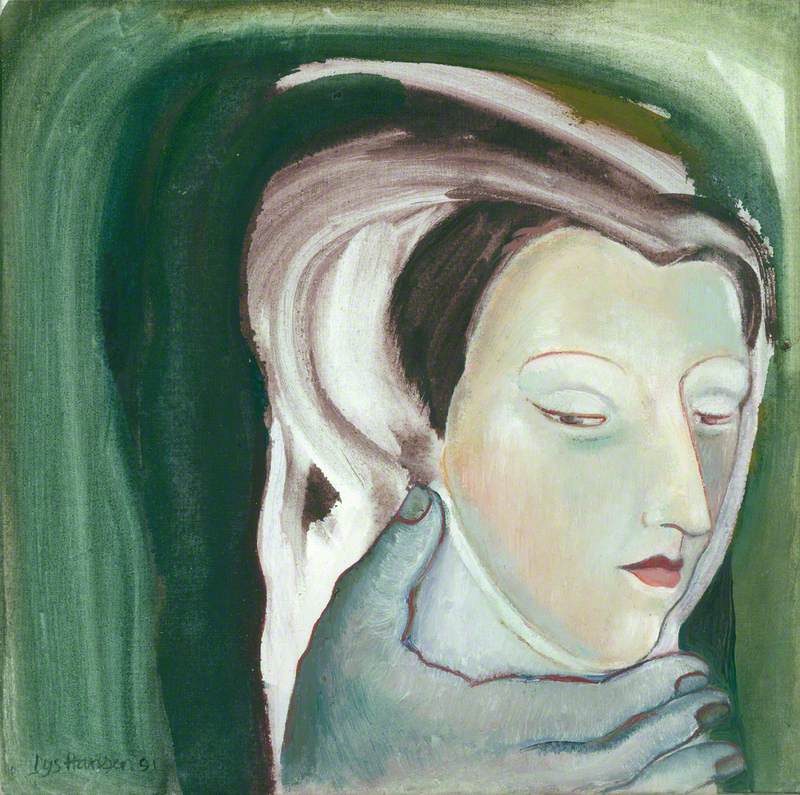

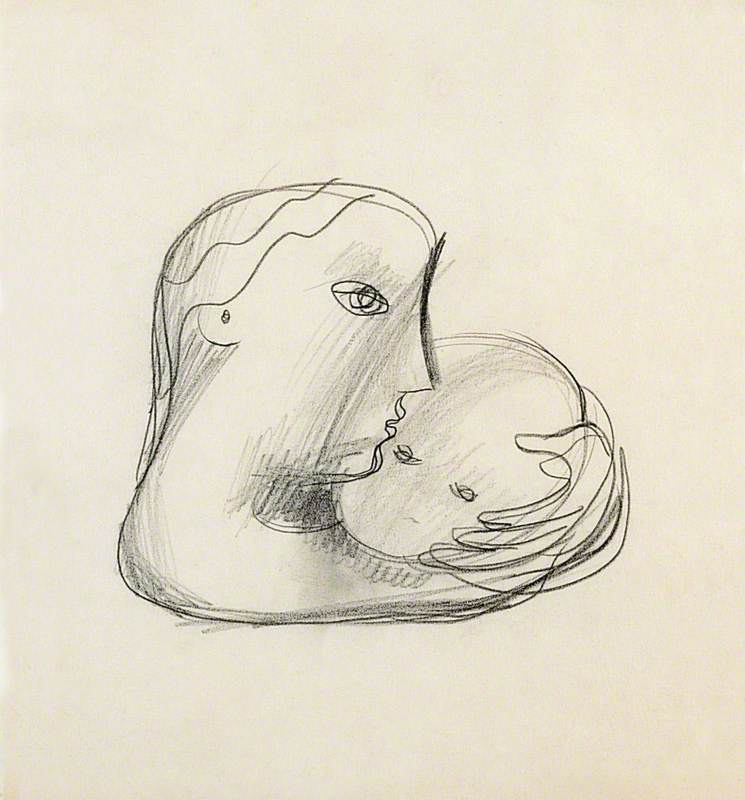

'Thou knowst thou hast made me with passions wild and strong' No. 2

1996

Lys Hansen (b.1936)

In his 1992 work Contemporary Painting in Scotland, art historian Bill Hare described her as one of the country's 'most powerful expressionist artists', yet many supporters believe Hansen has so far failed to receive due recognition as one of Scotland's most important late twentieth-century figurative painters.

She was born in Falkirk, Scotland, in 1936, to a working-class family with a Danish father, providing important links to continental Europe. Hansen felt her upbringing was confining, although remembers her parents encouraging interest in the arts. That she grew up in the shadow of the Second World War proved to have a long-standing impact, leading her to empathise with deep trauma. This can be seen in such powerful works as Berlin Diptych: Look and Listen (1993–1994).

An exhibition dedicated to Hansen's work at Callendar House in Falkirk, 'Live It Paint It', notes the importance of the artist's education on her development. From 1955–1959, she studied drawing and painting at Edinburgh College of Art (ECA), before focusing on fine art at the city's university. Then, Scottish Colourists such as Samuel John Peploe and John Duncan Fergusson were still revered.

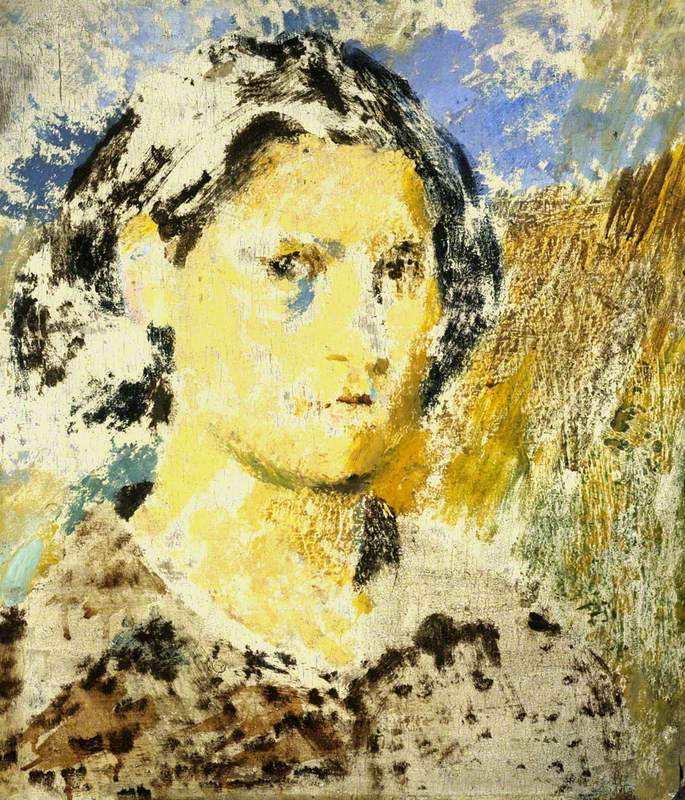

Lys Hansen at the preview of 'Live It Paint It'

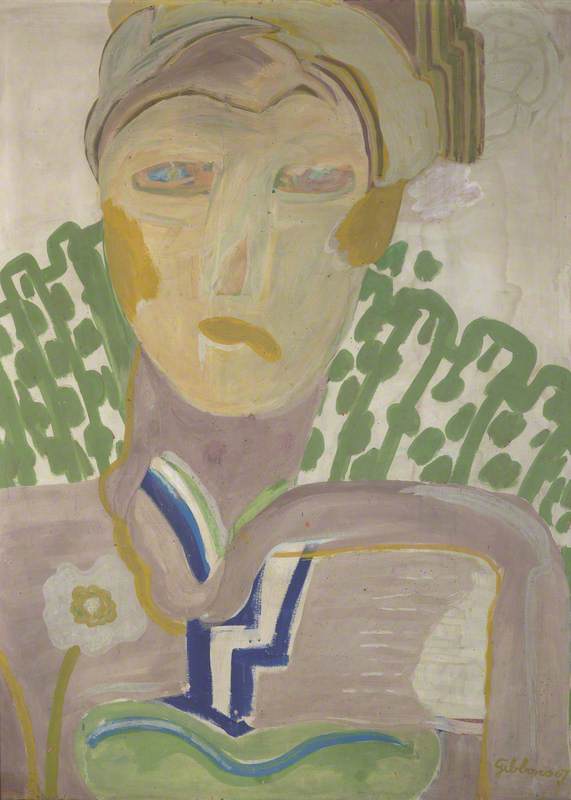

Celebrations of light and colour were also key to the more contemporary Edinburgh School artists, among them her tutor William Gillies, John Maxwell and Anne Redpath.

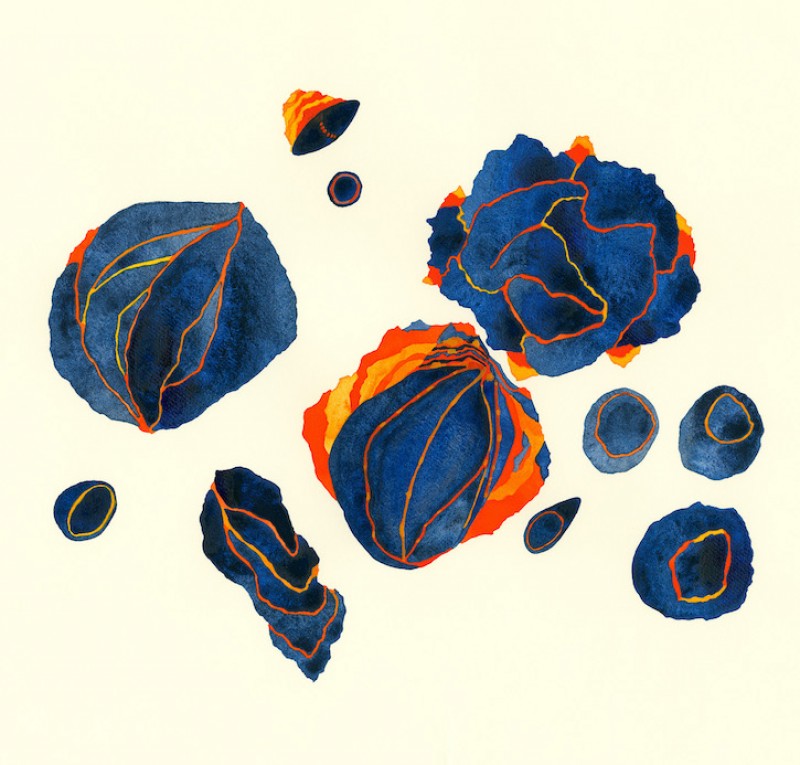

Hansen herself adopted a light palette and exuberant use of colour, attracted especially to the binary opposition of red and blue, as seen in Act I Scene II (Duet) (1987). Hansen described the former in an interview as 'the aggressive male colour' and the latter as 'the nurturing of the Madonna, and the infinity, the sky'. In other ways, Hansen's education proved more constrictive. In her essay The Grand Dame and the Canvas Ceiling: Lys Hansen, Glasgow School of Art's (GSA) academic lead Marianne Greated relates how her subject found ECA to be a patriarchal, male-dominated environment.

This state of affairs continued into her teaching career, which included GSA. In the 'Live It Paint It' catalogue, Callum Stark, a history of art graduate at the University of Cambridge, relates how Hansen once gave a life drawing class, encouraging the female model to take on 'unconventional, and resolutely active poses', which her superiors later complained about.

Elsewhere in the catalogue, Hare, honorary fellow in history of art at Hansen's alma mater, explains how her immersion in the subject enabled the artist to enrich her paintings with 'subtle allusions' to wide-ranging sources. Among them is one of her favourite artists, Edvard Munch, alongside Francis Bacon and the violent brush strokes of Willem de Kooning. You can certainly find aspects of Picasso's cubism in her portrayal of an anonymous figure in Other Directions (2007).

Pointedly, while many of these masters have subjected female nudes to what Laura Mulvey dubbed the 'male gaze', Hansen has portrayed women in a more empathetic manner, drawing out their interior thoughts and societal situations. This applies as much to a historical figure such as Mary, Queen of Scots (1991) as the defiant model in Stance (1983).

Notable with the latter is its difference to classical forms that reflected ideals of the female body and used the passive poses that Hansen's GSA colleagues preferred. During her painting degree, Hansen took time out to work as a fashion model while also studying dance and performance, which Greated sees in her figures' sense of expressive movement. This is especially apparent in Hansen's focus on hands as a means of suggesting feelings or emotional states, seen in many works, including Resting with You (1988).

Yet it took until the 1980s for Hansen to become established as an artist. Following a postgraduate course, she completed teacher training, as expected of female graduates at that time. Hansen went on to marry and bring up two children, supported by teaching in art schools and colleges – including lectures on 'the nude' for the Scottish Arts Council (SAC).

She began to focus on her own practice only when she reached her 40s and family commitments became less pressing, though soon enjoyed early success. This coincided with a renewed interest in painting across Europe and North America , especially figuration and expressionism. In Scotland, this was seen through the rise of the New Glasgow Boys, named after the original Glasgow Boys who had portrayed more grittier scenes than the Colourists. Among them were the likes of Peter Howson and Ken Currie.

Hansen gained a major award from the SAC that enabled her to spend time in Berlin in 1984, where the neo-expressionist style was focused. Here, large-scale canvases had become popular, notably among such rising stars as Anselm Kiefer and George Baselitz, influencing the scale of Hansen's own works. She also grouped works together to extend their size even further, as in the previously mentioned Berlin Diptych.

Emerging at a time when few female artists prospered, Hansen has been seen as a trailblazer for Scottish women artists that have followed her in engaging with the female figure, among them Jenny Saville, Alison Watt and Helen Flockhart. During the 1980s, she was especially active in promoting women's art in her home country, speaking at the groundbreaking Women Artists Conference '83 in Dundee. Fellow speaker Liz Lochhead was inspired to write her poem Dreaming Frankenstein (1983), which she dedicated to Hansen, among others.

This work became the title of a collected poems, for which Lochhead selected one of the artist's drawings as its opening illustration. Hansen, meanwhile, went on to lead a session at the next year's Women's Art Conference Glasgow, held in March, the same month as her debut solo show, with both end dates coinciding. Greated sees this as a key moment both in Hansen's career and a feminist movement in art, writing: 'It was a coming together of creative minds, galvanising a community and marking the start of a new era for artists who were women in Scotland.'

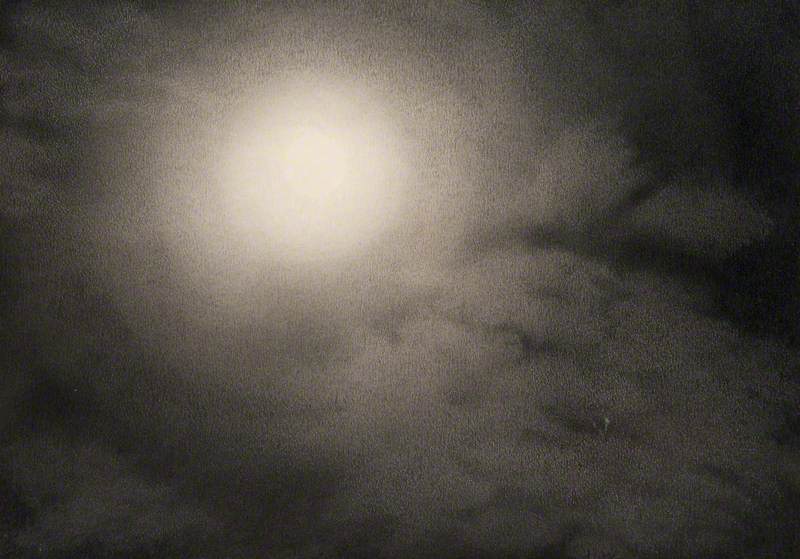

Visitation at the Blocks

by Lys Hansen (b. 1936)

For Hansen, meanwhile, this period provided 'an engagement with other women artists and the understanding that there were other artists facing similar challenging issues'. Later that year, she appeared in the BBC programme The Lunch Party, discussing her career with two other Scottish female artists, Pat Douthwaite and Jacki Parry. Hansen explained that being a woman defined her work, asserting men saw women differently to how women saw themselves. Greated quotes Hansen in response to Douthwaite: 'You can't see things like a male sees them, because you are not male. I don't think a man could paint the way you paint, Pat. I don't think he ever sees the female like that.'

Having established herself as an artist, although at one remove from any particular scene, Hansen has continued to focus on the female form. Maintaining her creativity into into her eighties, she has experimented in other media, including devising three-dimensional paintings using found objects such as tree branches to create assemblages. In the catalogue to the Falkirk show, Greated writes: 'Hansen lives life to the full and the act of painting is at her core. She lives it and paints it.'

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Lys Hansen – Live it Paint it' runs at Callendar House, Falkirk, until 11th August 2024

This content was supported by Creative Scotland