Did you know that beauty spots were often used to conceal smallpox scars and syphilis sores? Or that powdered wigs were a way to disguise baldness from venereal disease?

Sexual diseases are as old as humankind. Although today most sexually transmitted diseases are easily treatable, they were once totally incurable. Sufferers endured rotting flesh, the prospect of insanity and the likelihood of death.

This darker side of history is reflected widely in European art history, as the patrons, sitters and artists themselves were often the sufferers of these grisly and contagious diseases.

Here's a short history about how syphilis became a central theme and subject in European painting. Continue scrolling if you want to find out more (or click away if you are particularly squeamish).

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

An Allegory with Venus and Cupid about 1545

Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572)

The National Gallery, LondonOne of the most notorious paintings to explore the theme of sexual disease is An Allegory with Venus and Cupid (c.1545) by Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572), which can be found in The National Gallery.

A Florentine painter who was commissioned to create this work by Francis I, the King of France, Bronzino's painting is rich with symbolism. Not only is this depiction an erotic allegory of love, but it also conflates desire with disease. Art historians noted that the figure on the left-hand side – painted in a sickly greenish-hue – represents jealousy, but also symbolises 'neurosyphilis', the term given to untreated syphilis when it spreads to the brain and spinal cord.

The art historian J. F. Conway observed in 1986 that not only are the teeth missing – a sign of mercury poisoning – but that the fingernails are also absent: another sign of advanced syphilis.

In the decade that Bronzino was working on this painting, syphilis had gripped Europe. It was a type of venereal disease, i.e. one that was contracted through sexual activity. The term 'venereal' originates from the figure of Venus – the Roman goddess of love, who is also an embodiment of female sexual persuasion.

So what is syphilis?

Syphilis is a disease caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium called Treponema pallidam. First causing a painless ulcer, it then rapidly and insidiously spreads to the vital organs of the body.

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Sores and Pustules on the Hand and Arms of a Woman Suffering from Secondary Syphilis 1858

Christopher d'Alton (active 1847–1871)

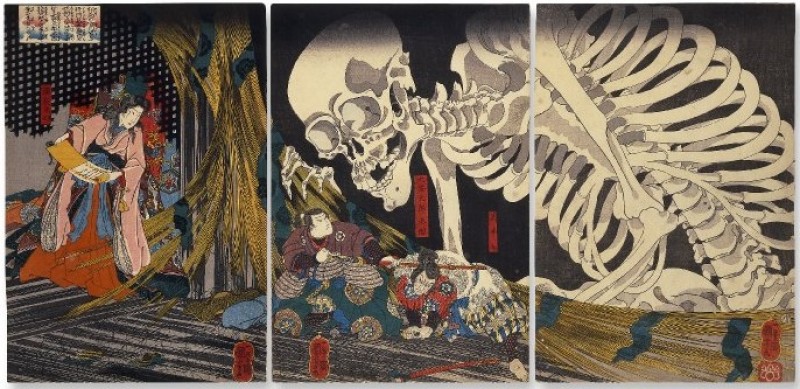

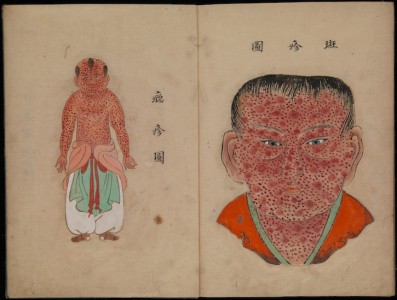

Wellcome CollectionAlthough historians dispute the origins of the disease, many believe that syphilis was first brought to Europe when Christopher Columbus returned from the New World in 1493.

Alternatively, it has been argued that the disease originated during the Italian War of 1494–1498, breaking out amongst the French troops of Charles VIII who besieged Naples. Upon realising there were chancres upon their genitals, the soldiers then experienced itchy rashes and weeping pustules.

Consequently, the Italians called it the 'French disease' and the French called it the 'Neapolitan disease'.

In the aftermath of the battle, it swept across the entirety of Europe. Spreading from east to west, the Russians called it the 'Polish disease' and the Poles called it the 'German disease'. In Britain (perhaps because our neighbours were further away) it became widely known as 'the great pox', although many referred to it as the 'French disease'.

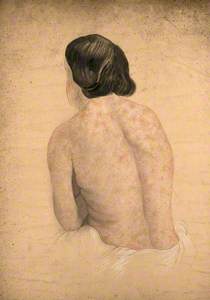

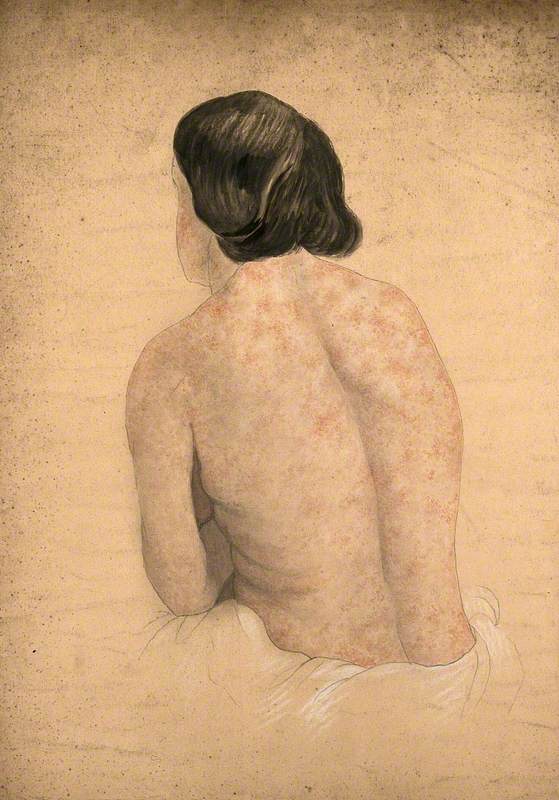

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Back of a Woman Suffering from Skin Covered in a Rash Caused by Syphilis 1862

Christopher d'Alton (active 1847–1871)

Wellcome CollectionOnly in 1530, did the infection acquire the name 'syphilis' when the Italian poet Girolamo Fracastoro wrote 'Syphilis sive morbus gallicus', an epic poem about a shepherd called Syphilis who, upon angering the god Apollo, was cursed with a terrible disease.

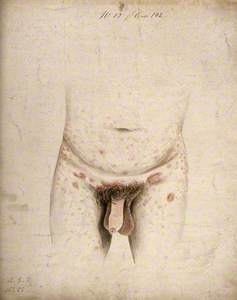

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Diseased Skin and Sores on the Leg of a Man Suffering from Syphilis 19th C

Christopher d'Alton (active 1847–1871)

Wellcome CollectionBy the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the scientific literature around the illness was quite extensive. However, there was still no cure.

When the German physician Joseph Grunpeck (1473–1532) became infected, he described it as: 'so cruel, so distressing, so appalling that until now nothing more terrible or disgusting has ever been known on this earth.'

By the seventeenth century, a severe and widespread phobia of the disease came into existence and was coined 'syphilophobia'. In 1676, the physician Richard Wiseman described the emergence of this paranoia. He wrote 'many of these hypochondriacks have come to [me]. They commonly went away... unsatisfied, nor could they quiet their minds til they found some undertake that would comply with them.'

During this period, quack doctors often made a profit by trading on the fears of syphilophobes.

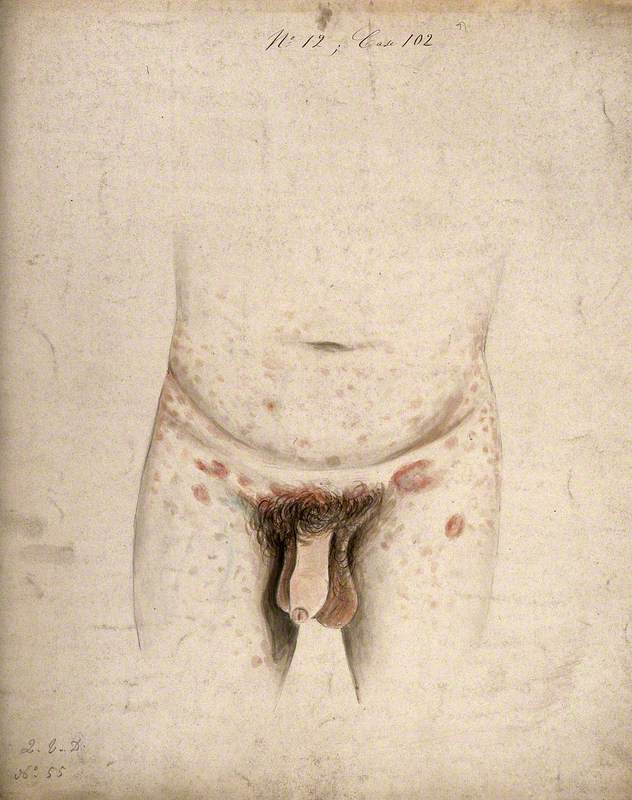

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

The Diseased Genitals, Groin, Abdomen and Upper Legs of a Man Suffering from Syphilis Roseola 19th C

Christopher d'Alton (active 1847–1871)

Wellcome CollectionThe promiscuous lothario Casanova allegedly had eleven bouts of syphilis, all of which he treated with mercury – a poisonous substance often used to combat the disease.

Before penicillin was invented in 1928, mercury was widely used to treat the unrelenting symptoms, giving rise to the saying: 'One night with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury.' Mercury was applied as an ointment, inhaled in a steam bath or ingested as a pill.

Image credit: Newnham College, University of Cambridge

The Harlot's Progress (plate 2)

William Hogarth (1697–1764) (after)

Newnham College, University of CambridgeIn the eighteenth century, fake moles were created largely in response to the outbreak of smallpox but also sexually transmitted diseases. The French even created a term for these artificial facial decorations, 'mouches' (also meaning 'flies' in French). In this era, mouse fur was commonly made into facial patches to mask facial imperfections.

The image of the beauty mole started to frequently appear in satirical representations. For example, William Hogarth (1697–1764) often painted characters with black beauty marks as a way to show a debauched, aristocratic society.

Image credit: The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

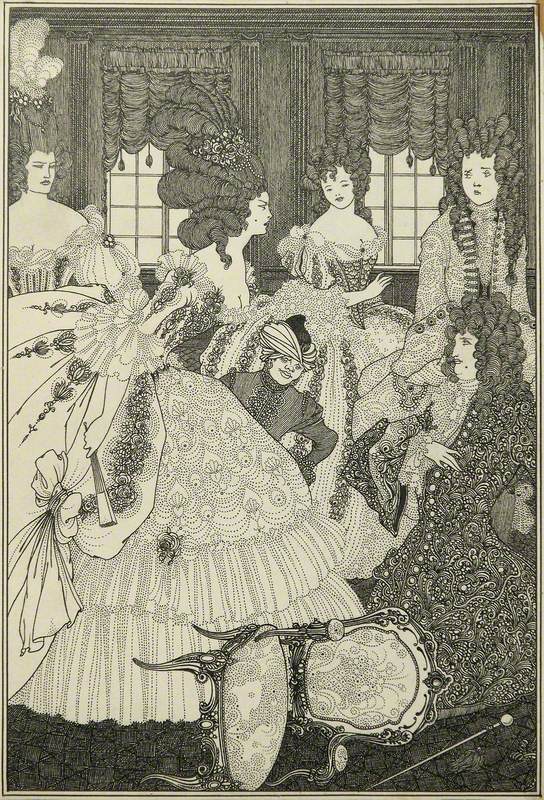

The Battle of the Beaux and the Belles c.1896

Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898)

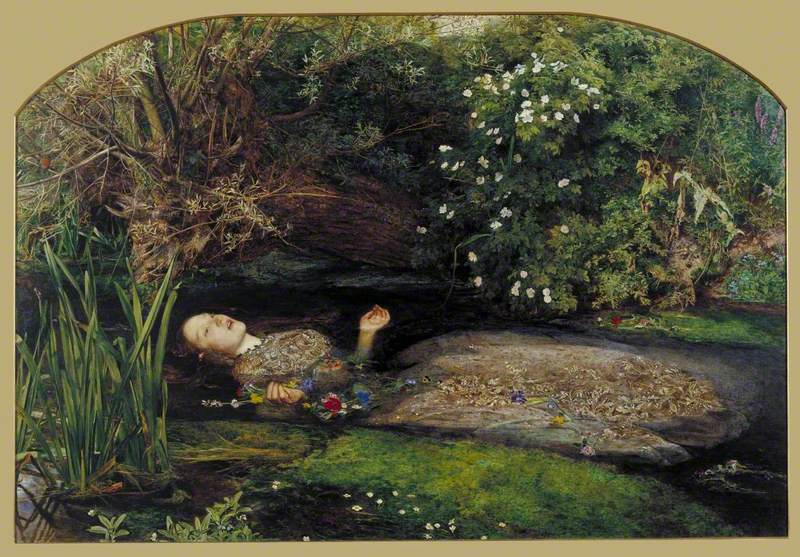

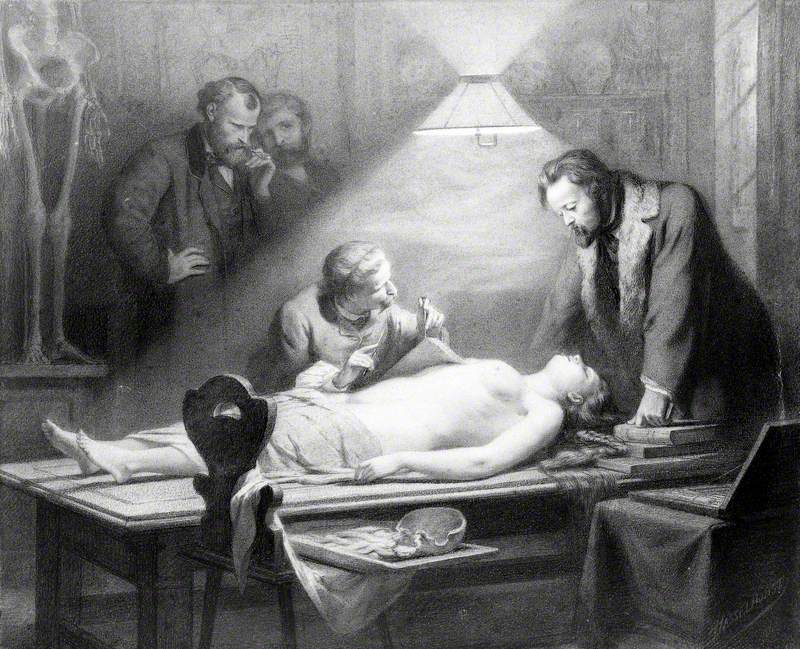

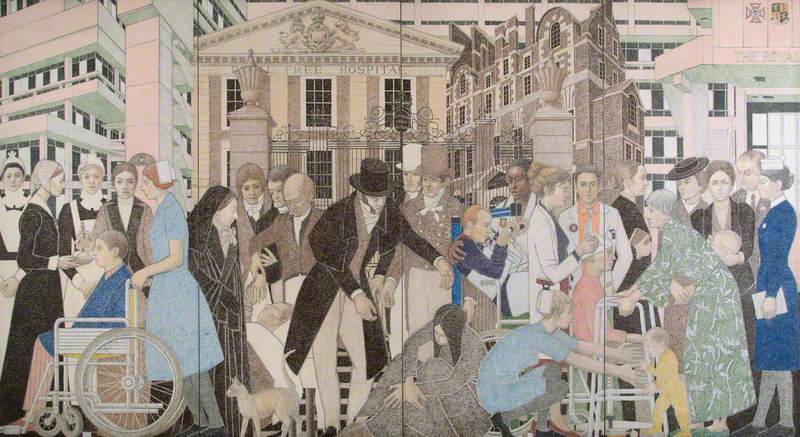

The Barber Institute of Fine ArtsIn the nineteenth century, syphilis remained an incredibly virulent and ubiquitous disease, despite advancements in medicine and microbiology. Watercolourists such as Christopher d'Alton (1847–1871) began to depict in graphic detail the bodily effects of syphilis.

During this era, the sex work industry and prostitution – known as 'The Great Social Evil' – became increasingly commonplace, meaning there was an epidemic of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Connotations of 'loose women' were associated with venereal disease.

The British government became so fearful of the disease – believing it could possibly kill soldiers and sailors – that they passed the Contagious Diseases Act in 1864. This law allowed police to forcibly detain women they believed to be prostitutes, allowing them to examine them for syphilis or gonorrhoea.

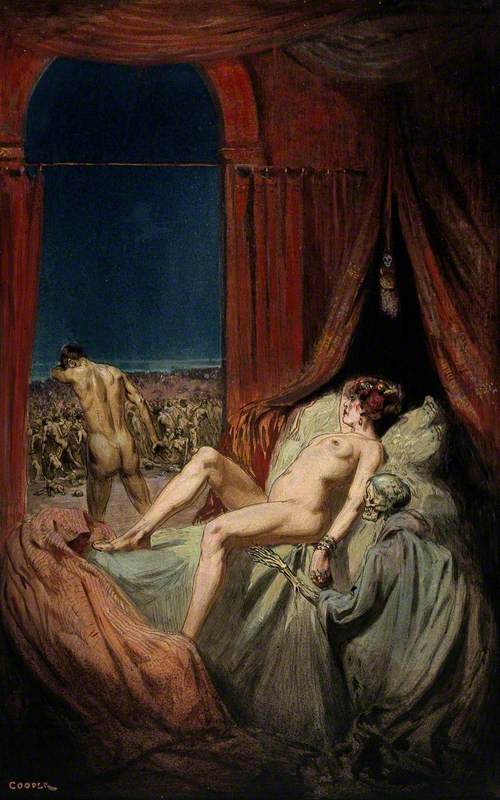

Images by Richard Tennant Cooper (1885–1957) reveal the Victorian preoccupation with syphilis and the associations of sexual deviance with disease.

Within these paintings, the figure of the female prostitute is depicted as the omen and bearer of disease, while the man is presented as an innocent victim, overpowered by female sexual prowess.

Known for being a regular visitor to the Moulin Rouge, whose glittering yet seedy nightlife he found fascinating, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) contracted syphilis, eventually dying from the disease.

Jane Avril in the Entrance to the Moulin Rouge, Putting on her Gloves c.1892

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)He allegedly contracted it from Rose La Rouge, a prostitute who was often the subject of his paintings.

Described as an ageing 'coquette', this painting shows Lucy Jourdan, another high-class prostitute at the Moulin Rouge who Toulouse-Lautrec frequented.

In a Private Dining Room at the Rat Mort c.1899

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)According to fellow painter Edouard Vuillard, Toulouse-Lautrec found 'an affinity between his own condition [i.e. his smaller stature] and the moral penury of the prostitute.'

Alas, his nighttime adventures at the Moulin Rouge led to his early death aged 36 of both alcoholism and syphilis. A few years later, the leading Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) also allegedly died from syphilis.

Other significant cultural figures who were gripped by the merciless disease were Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Guy de Maupassant, Charles Baudelaire, Gustave Flaubert, Vincent van Gogh, Friedrich Nietzsche, Oscar Wilde and James Joyce.

Towards the end of their lives, most of these figures experienced a serious psychological decline, something which historians have attributed to the toxic therapeutic consumption of mercury.

There is no moral to this sickly tale, except to say that if you are experiencing any of the symptoms described above, please visit your GP promptly...

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK