Rather like Picasso's, Thomas Gainsborough's life can be divided into distinct periods. In his case, three phases are defined by places of residence: the early career until 1759 being spent in East Anglia and London; the middle, 1759–1774, in the West Country town of Bath; and the final years from 1774–1788 in London.

The late London paintings are very different from those of his youth, but no dramatic stylistic changes mark the transition from one place to the next: the path towards an increasingly free and idiosyncratic way of painting was an evolutionary one. The last, late period is the subject of my book Gainsborough in London.

The Honourable Mrs Graham (1757–1792)

1775–1777

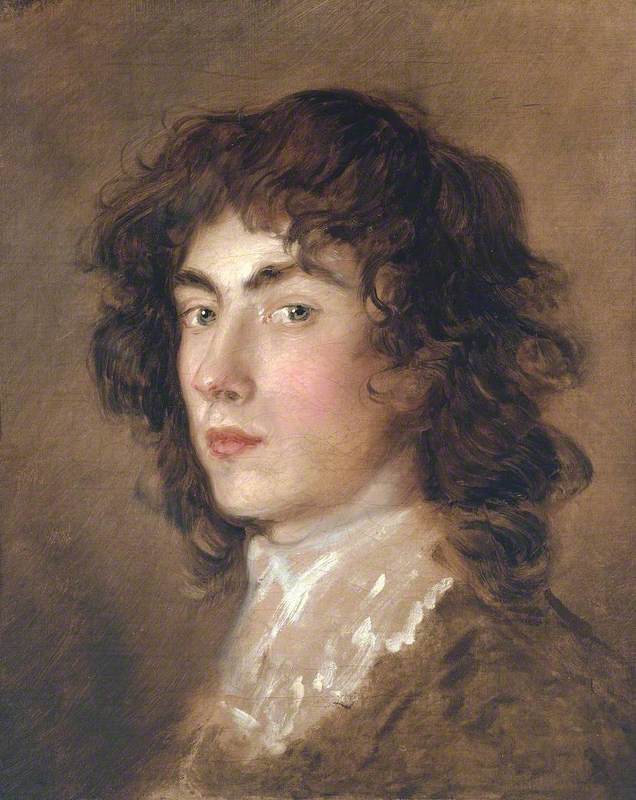

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

In Bath, Gainsborough's portrait practice prospered. His rapid technique and ability to capture good likenesses suited the seasonal comings and goings of his clientele and he deliberately situated himself in prestigious and convenient premises. At the same time, he sent paintings to the new annual exhibitions of contemporary art in London as a means of maintaining a national profile and of reminding competitors of the seriousness of his ambitions.

Only royal patronage evaded him, and this must have been the impetus for his decision to uproot and settle in Pall Mall. The opening chapters of Gainsborough in London look at where and how the artist painted and displayed his work. The rooms that he threw open to visitors are considered in the context of the public exhibition rooms, all of which were then in or immediately off Pall Mall, and of other painters' properties.

It has not been noticed before that several of London's leading artists, notably Joshua Reynolds, Benjamin West, John Hoppner and Gainsborough himself, organised themselves in a remarkably consistent fashion, in premises similarly configured. All lived in terraced houses behind which were freestanding single or double-storey outbuildings designed to provide painting room (studio) spaces and galleries. The rear buildings were generally reached by a long passageway or corridor from the street, sometimes via an independent extra front door, the passage acting as a secondary display area, as well as a means of guiding visitors to the commercial quarters.

The home that Gainsborough selected, 87 Pall Mall, was the west wing of Schomberg House, an old mansion that had been divided into three dwellings in 1769. Not only was it close to several royal residences, but it had itself been occupied for a short period by Princess Augusta, sister of George III.

The house was 'fitted up' for the princess who came from her marital home in Brunswick to be near her mother, the Dowager Princess Augusta when she lay dying at Carlton House between the autumn of 1771 and mid-February 1772. Gainsborough may well have acquired some of the furnishings installed for the princess when he moved in two years later. Each of the three parts of Schomberg House appears to have had its own outbuilding. The rooms at the back of the east wing, 89 Pall Mall, were occupied by a succession of drapers and milliners.

The centre, No. 88, was home to the portrait painter John Astley and passed to the quack doctor James Graham, who gave public lectures on fertility and rented out a 'Celestial Bed' in what he called 'The Temple of Health and Hymen'. Graham also hosted 'EO' gambling tables, and it was this forerunner of roulette, 'Even-Odd', that caused disturbances and even a murder in Schomberg House in 1782.

Gainsborough must have breathed a sigh of relief when the painters Richard Cosway and Maria Cosway succeeded Dr Graham as his family's immediate neighbours in 1784. All that survives of Schomberg House is the thin street-facing north façade, and much of that is in a rebuilt form. Drawings, plans and surveys that are published for the first time in this book give an idea of the eighteenth-century layout and appearance of the building.

London newspapers commonly reported on the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy, Society of Artists and Free Society of Artists, but Gainsborough ensured that paintings in progress or hanging on his own showroom walls were also mentioned in the press. Visitors, any of whom might be potential clients, could be enticed in to Schomberg House by passing references to glamorous sitters.

George (1762–1830), Prince of Wales, Later George IV

1781

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

On 25th August 1781, for example, The Morning Herald, under the editorship of Gainsborough's friend Henry Bate, noted that portraits of the Prince of Wales, Mrs Grace Dalrymple Elliott and Mrs Mary Robinson were being painted or were just finished.

Grace Dalrymple Elliot

c.1782, oil on canvas by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

Mrs Elliott's and Mrs Robinson's are described as 'rival portraits' since both women were mistresses of the prince. Their likenesses were guaranteed to attract public interest. The actress Mrs Robinson was said by one contemporary to have a curiously melancholy appearance, 'languid and unimpassioned', something Gainsborough seems to have captured to perfection.

Mary Darby (1758–1800), Mrs Thomas Robinson ('Perdita')

1781

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

The rival mistresses were painted for the Prince of Wales, who, however, failed to pay the artist. Some other portraits of celebrities were not commissioned in the first place, but created purely for the showroom. Gainsborough had also always produced landscapes on a speculative basis and in the 1780s he expanded his repertoire to include coastal scenes, fancy pictures and even sporting subjects.

A Fox Hunt and its companion picture of deer, which is now lost, are two that seem to have been made expressly for display at Schomberg House, painterly tours de force designed to show off the range of his imagination and his formidable technical skills. Hounds Hunting a Fox, which is normally dated to c.1785, owes much to seventeenth-century Flemish models, in particular works by artists of Rubens' circle such as Frans Snyders.

We do not know where or how Gainsborough acquired the five canvases by Snyders (or at least said to be by Snyders) that hung at Schomberg House, but his friend the art dealer Thomas Harvey of Norwich was in the 1780s importing paintings of this sort via the ports of Rotterdam and Yarmouth. It is even on record that in 1786, Harvey was in correspondence with an Antwerp dealer about a Foxhunt and Dogs by Snyders' brother-in-law Paul de Vos.

Gainsborough's own Fox Hunt and the companion painting of deer were, like the paintings by Snyders, still on the premises at the time of his death. His late experiments and excursions into new territory were signs of the painter's wish to leave his mark on the history of European art. He did not want to be remembered as 'just' a portrait painter.

Leonardo da Vinci's writings had been translated and published in England in 1721 under the title A Treatise of Painting. There, it is said that the most praiseworthy artist is the one who is most versatile; he must 'be Universal and apply himself to the Study and Consideration of all Objects'. Gainsborough would certainly have been conscious of the Treatise, and it is noticeable that in the 1780s his allies in the press regularly drew attention to his 'universal genius'. It was widely read in late eighteenth-century London: the landscape artist Alexander Cozens quoted from it in his own theoretical writings and the portrait painter Daniel Gardner had a copy on his bookshelf. It was among the books recommended to the young John Constable in the 1790s.

Schomberg House was the showcase, the place where Londoners could view Gainsborough's work alongside Continental paintings and make up their own minds about the nature of the genius in their midst.

Susan Sloman, author of Gainsborough in London published by Modern Art Press