Leaves, birds, fruits and flowers. Motifs of delightful nature and the tranquil outdoors. The art of the Rococo era was enjoyed by the privileged to take light-hearted scenes indoors. Snapshots of picnics, known as the fêtes galantes, and furniture fortified with gilded wildlife and plants transformed interiors into a heavenly echo of basking in the garden. The Rococo was a rare time when painting communicated with ornaments and a room could transport you from indoors to outdoors.

The term 'rococo' is derived from the French word 'rocaille', meaning rock or broken shell. The very definition of this art ruled for nature to be captured for decoration. It is worth noting that Voltaire, the French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher, criticised it as 'degenerate' and 'superficial'. It is true that Rococo art often had no deeper mission than to please the viewer or to make jolly. The colours, motifs and entertaining scenes brought the fêtes galantes as a continuous party in the homes of the rich.

Fêtes galante is a type of painting – made popular by Jean-Antoine Watteau, an early Rococo painter – that depicted wealthy men and women in parkland making jolly, flirting and enjoying entertainment. This pastime was a privileged activity for the happy rich and the fine art capturing it was reserved for their walls.

While fêtes galantes were a trend in painting, the same ideas were paralleled in furniture and decorative arts. The idea was to implant the charm of nature into the inanimate: to freeze summer and make it last all year long.

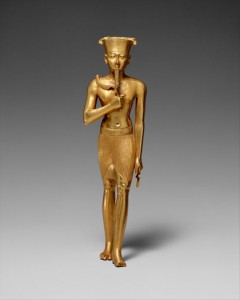

Taking a look at this torchère (a mix between a floor lamp and a candelabra), you can spot the obvious ode to nature in the leaves and flowers that embattle the structure.

Torchère

1720–1750, softwood, carved & gilded by an unknown French maker

Yet the very shape of the object projects movement and life. These kinds of objects feature 'S' forms, as you can see here in the swaying outline of the floral base, to the knees of an infant Triton (a sea god), and to the basket of flowers the infant holds up.

Looking closely, there are countless more 'S' shapes, such as the feet of the torchère, the drapery the infant holds and swooshing leaves in the flower basket. Divine childhood and foliage in blossom are forever carved in the gilded wood of this decadent household item. Gilded interiors, along with paintings, captured the season inside parlours and chambres.

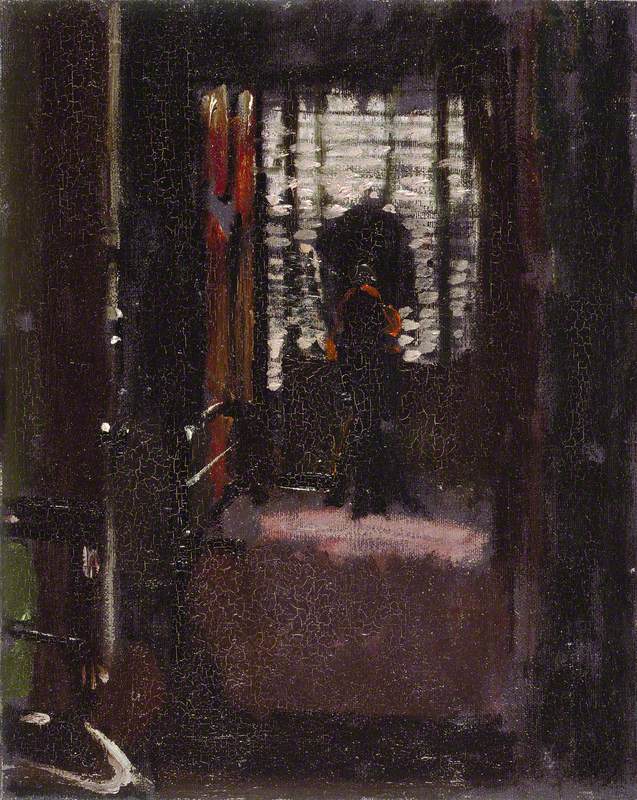

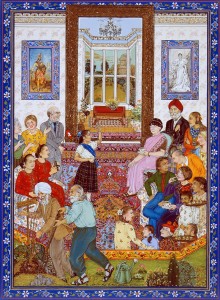

Look at the people in this picture – they are dressed their best and wearing happy faces.

A Scene from the Commedia dell'Arte with Harlequin and Punchinello

1734

Nicolas Lancret (1690–1743)

It is an example of the undying endeavour to publish sunny images, as we do today to capture the fleeting moments of summer. People painted in fêtes galantes were emblems of humour, happiness and ease. It would not be common to find a serious scene or downtrodden individuals. On instances when characters of a lower class were included, these people were usually part of the fun – happily serenading the protagonists with music, scandalously chasing ladies or putting on some comedic theatre.

Blind Man's Buff (Le colin-maillard)

c.1730–1733

Jean-Baptiste Pater (1695–1736)

The art of the Rococo had the purpose of entertainment. The wealthy patrons of art wanted their homes to be delightful and ornate. Sometimes the scenes painted had moral lessons behind the humour, but other times they were intended only to please. There were the games such as le colin-maillard (blind man's bluff, as played in the painting above). There were musicians inspiring dancing – as makes any good party! And there was comedy theatre.

Commedia dell'arte was a type of theatre where actors improvised jokes built with stock characters and situations. (Like the improv comedy of today!) The star characters of Pierrot and Harlequin can still be recognised as the clown (dressed with a ruffle collar) and the jester (in a cap 'n' bells hat).

In this painting, you can see Pierrot and Harlequin appealing for the attention of women – a common competition for these two rivals.

When today we feel how pestering this attention must be for the poor woman, to the viewer at the time, this would seem like party gaiety. And the things the two would do to succeed were hilarious.

Summer and Christmas seem to be the popular times to strike a romance in movies. Not much has changed in over 200 years. Instead of blockbusters, the people of the eighteenth century took their enjoyment and awe from romantic paintings. These scenes were a sort of rom-com: the men pining for the women, the coying women flirting the men closer and playful situations of teasing.

In this scene, two men are bowed down and competing for the attention of the lady in a musical contest.

There is a funny contrast in the positions of the woman and the men, the men kneeling and slumping below her make them look small and feeble and the woman large and confident. A particularly silly moment is the man who is clinging to her in a pitiful plea. This dynamic between men and women was a popular theme in this genre of painting as it derived humour from lamenting men. Another very Rococo motif that can be spotted in this painting is the background where you can see stone mythical characters poking through the leafy green.

Cherubs and juvenile gods, such as Cupid and infant Triton, were celestial symbols of love or purity or budding power. In this bronze sculpture of Cupid by Falconet, there is a single rose with its thorns and leaves laying on our left next to Cupid.

This blends the nature and mythology motifs of Rococo works and merges love with the playfulness of this boy's expression.

As we have seen, leaves were a key image in Rococo nature scenes and fêtes galantes, but these were also reflected in objects of everyday use for the wealthy. Here is 'pot pourri Hébert', a vase for potpourri to perfume the apartments of its noble owner.

Potpourri Vase and Cover Vase, 'pot pourri Hébert'

c.1760, soft-paste porcelain, painted & gilded by Manufacture de Sèvres

The reserves (the painted pictures on a decorative object) show the motifs of birds and trees. The gilded foliage and peacock feathers immortalise the golden flowers to never wilt or fade, even in winter.

Arranging flowers is a delightful task to fill the home with the harvest of blooms, filling rooms with the scent of summer and bringing the beauty of nature inside.

Many of the Rococo ideas of summer joy are still used today: have a picnic, decorate your home, enjoy outdoor theatre, play some garden games, have a summer romance and have some summer fun.

Tegan Huskinson, writer