A 'queero' – queer hero – is defined as 'an LGBTQ hero/a gay role model/aspirational queer identity'.

Pop culture, media, sport and education seeks the queero in culture – it's a powerful and valuable moment in reclamation for queer communities. Systematic destruction, removal or omission of history leaves a deficit in shared identity. Queer role models become harder to find in history and thus more precious.

As we reach to the treasure trove of national art to find this, we have an incredible opportunity to rebuild lost history. In our excitement to do so, however, a note of caution. Deep within the artworks lies danger too – tread carefully, my dear queero hunter.

Artists and sitters in history are a product of their own sociology, not ours – when we apply aspirational status this cannot be at the cost of uncomfortable truths. Multiple readings of history can also be multiple opportunities to wound us. Furthermore, are we right to apply an identity to historical figures they themselves did not use or would accept?

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

King James I of England and VI of Scotland 1621

Daniel Mytens (c.1590–1647)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonThe seventeenth century was a time of dynamism, tragedy, drama and some excitingly camp aesthetics – its temping to look there. James (VI of Scotland, I of England) is a great starting point. Compelling historical evidence suggests as well as being married to Anne of Denmark and fathering children (including the future Charles I), James also enjoyed a series of male romantic and sexual relationships in his lifetime.

Image credit: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow

King James VI and I (1566–1625) 17th C

Paulus van Somer I (1576–1621) (circle of)

Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of GlasgowThe word 'favourite' bellows to queer audiences in coded messaging. A leader of countries living a known queer life? Surely worth celebration. For me, it's a no, sadly – any concept of queerness, bisexuality or a spectrum of identity did not exist for James as it does for us in culture today.

Sodomy existed solely as a choice in theology for James – an active sin, a form of depravation, a weakness. As head of the Church of England (and, head of the Scottish Kirk during a time of great reform), James would never have identified with this. Indeed, James offers evidence in history that supports this prejudice. James upheld punishment and death for the act of gay male love, and openly advised his son to avoid this in a published treatise called A Premonition to All Most Mightie Monarches in 1609.

Pragmatism wobbles precariously next to a projection of morality, and arguably an abuse of his power. Queer love was an entitlement for a king above the law, yet he was no ally to others.

Queero points 4/10

Perhaps his alleged lover, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, fares better?

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham c.1616

William Larkin (c.1585–1619) (attributed to)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonGlamorous and beautiful, he basked in the attention of the king. A true Antinous of his time, his portraits radiate queer energy and an unapologetic sexuality, noted particularly in his legs and lips.

Image credit: Cambridge University Library

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham

Michiel Jansz. van Miereveld (1567–1641)

Cambridge University LibraryDig deeper though and his rise to power was a calculated move by his family, noted by contemporaries for its design in attracting the king sexually in order to gain power. Again, Buckingham occupies a duality. While James appears besotted, this was no great queer love story, rather queer bating for profit, arguably. A successful queer courtesan certainly, but no hero of our time.

Queero points 4/10

Queen Anne, last British monarch of the century, is similarly seen by modern audiences as the darling of queer identity thanks to a recent cinematic release – the Oscar-winning The Favourite.

Much is made of her relationship with Sarah Churchill and the (disputed) evidence suggesting a romantic and sexual union.

Image credit: Wokingham Town Hall

Sarah Churchill (1660–1744), Duchess of Marlborough

Michael Dahl (1659–1743) (attributed to)

Wokingham Town HallExciting to see perhaps, but we must also recognise that this relationship bears all the hallmarks of abuse – manipulation for profile and political power, public belittlement and verbal abuse, strong indicators of control, and arguably abuse of a vulnerable adult. A powerful moment in queer history, absolutely. A positive one? Not necessarily.

Queero points 5/10

Here's someone you may not have heard of – seventeenth-century women's advocate Lady Catherine Jones. Born in 1672, this noble lady used both her position and wealth to support the education of young women. She is neither well known in British history nor carries the baggage of in-depth character research and its supporting material. The artist Willem Wissing painted her during her youth, and this print after his painting shows Lady Catherine with her sister and a black servant (Catherine is on the left in the print).

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The Lady Frances and the Lady Catharine Jones Daughters to the Right Honble Richard Earle of Ranelag

1691, mezzotint by John Smith the mezzontinter (1652–1743) after Willem Wissing (1656–1687) and Jan van der Vaart (c.1653–1727)

Lady Catherine herself was noted as having close relationships/residences with other women, and the magic phrase 'she never married' pricks up the ears of queero hunters in its coded message. Her implied queerness is furthered by her wish to be buried with a woman named Mary Kendall at Westminster Abbey, and Mary's equal wish that their ashes be mixed together.

Unmarried – check. Eternal rest with another woman – check. Advocate for other women – check.

Queer histories are inherently nuanced and rarely clear due to the underground nature of the lives lived. Catherine bears all the hallmarks of queerness as implied, yet is it fair to label her so? As an art historian, I encourage others to find queerness in art when it 'feels right' to them. Yet with few tangible characteristics, Catherine falls in danger of contemporary audiences projecting onto her our expectations – rather than what was authentically her lived experience.

Queero points 6/10

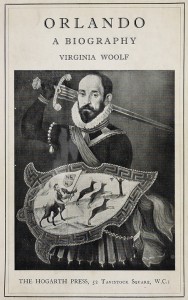

Queen Christina of Sweden, on the other hand, perhaps sets the benchmark for all aspiring queeros.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Queen Christina of Sweden (1626–1689), in Rome

Michael Dahl (1659–1743) (attributed to)

National Trust, Attingham ParkShe inspired both mockery and fasciation in her continued determination to live a life according to her terms. Famous for dressing in a masculine way, Christina, throughout her life, projected her own unapologetic gender identity through her clothes, mannerisms, and physical expression. As historians hide behind the term 'tomboy' awkwardly, we can see, as contemporary audiences, a woman who had both queer and heterosexual relationships, who revelled in being physically strong and active, and who rejected the imposed feminisation of her culture.

Christina made her own choices – she abdicated her throne, converted to Catholicism, moved to Italy and became a powerful patron to artistic communities (another screaming coded message there for you). Christina used her wealth and status to carve out a queer life path. No apologies, no explanations, no compromises.

Queero points 8/10

Each case is subjective, as is my reading of art history, and each is riddled with problems. As queer communities reach for an idol to match our contemporary expectations, it's painful to realise that few – or arguably no – historical figures can provide this. Perhaps instead of reaching into history to find icons, we can become our own hero. And in doing so, can historical figures instead become a springboard to question the heroes of today? Here's hoping.

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator