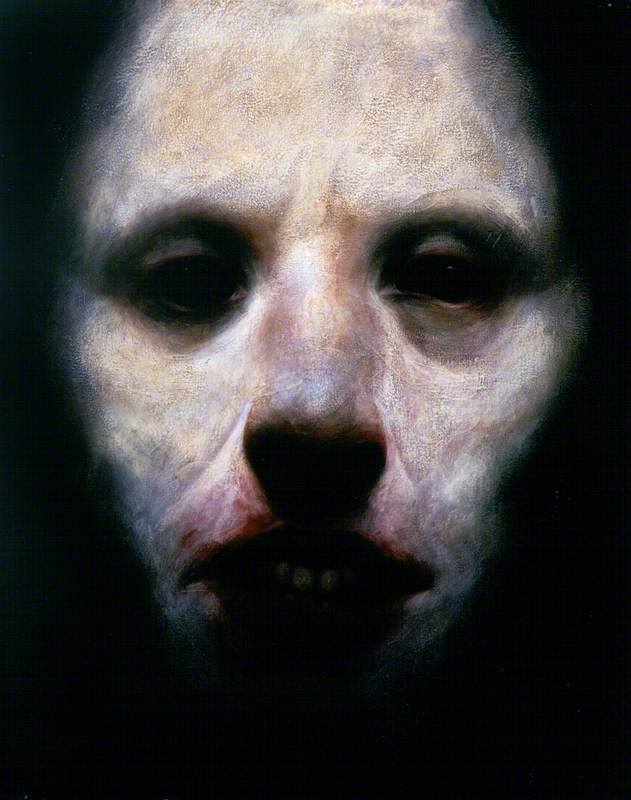

Scottish figurative painter Ken Currie (b.1960) is renowned for unsettling portrayals of human figures, often large-scale works full of drama – not least his uncanny Unknown Man, now in the permanent collection of the National Galleries of Scotland.

Despite its title, this is a portrait of one of the UK's most preeminent forensic anthropologists, Professor Dame Sue Black. She stands dressed in surgical robes behind the covered remains of a body – hence its moniker: Black's profession involves identifying remains and restoring the identity of the deceased. Currie had met Black during a Radio 4 discussion on the relationship between art and anatomy, inspiring the painter to ask her to sit for him. It is just one of several difficult and profound themes the artist has been drawn to throughout his career.

Indeed, Unknown Man joins another much-loved work in Scotland's national collection. Three Oncologists depicts a trio of innovators in cancer research at the University of Dundee and its affiliated teaching hospital, Ninewells. Emerging from darkness, Currie portrays his subjects as modern-day heroes in the battle against this life-taking illness.

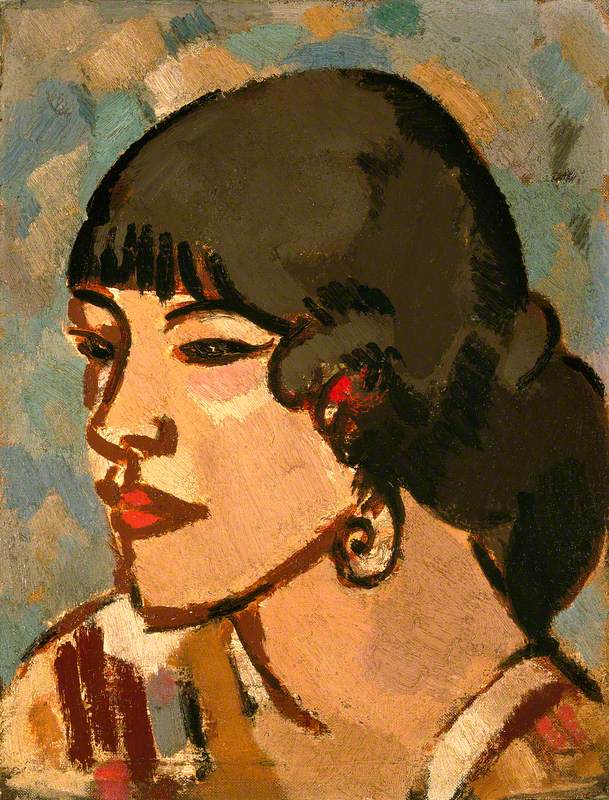

Born in North Shields in the north east of England to Scottish parents, Currie's family moved to Glasgow and he later studied at Glasgow School of Art between 1978 and 1983. Conscious of his working-class roots, Currie allied himself with his new home's history of socially aware art that dates back to the late nineteenth-century Glasgow Boys, such as James Guthrie and Edward Arthur Walton. They were known for depictions of ordinary life, so when a later generation of figurative artists emerged in the mid-1980s, they were dubbed the New Glasgow Boys or even Glasgow Pups.

Among them was Currie, alongside his peers Steven Campbell, Adrian Wisniewski and Peter Howson. Although they lacked a common style or agenda, all four were committed to figurative art, a form that had been on the rise since around the beginning of the decade. This group became key members of a cohort that showed their nation's art scene was vibrant, intelligent and in touch with the wider zeitgeist.

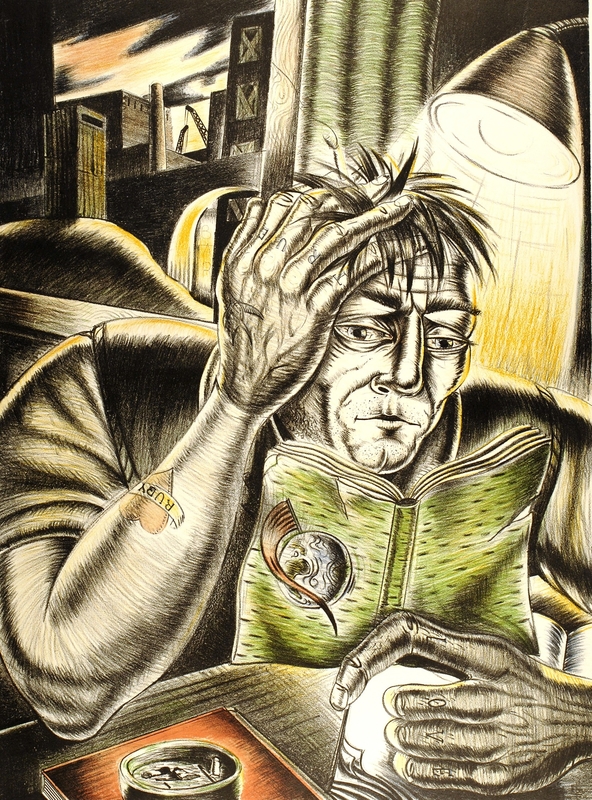

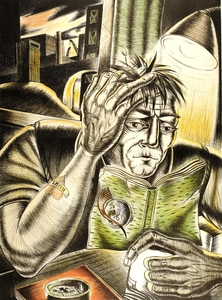

Their arrival was marked by the groundbreaking 1987 show 'Vigorous Imagination', held at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, the lead exhibition of that year's Edinburgh International Festival. Already proving himself to be among the most politically engaged of his peers, Currie showed a drawing, Self Taught Man. Its subject was inspired by autodidacts from his own family, one he turned to more than once. A linear style and use of block-like forms ensured his sentiments were clearly expressed.

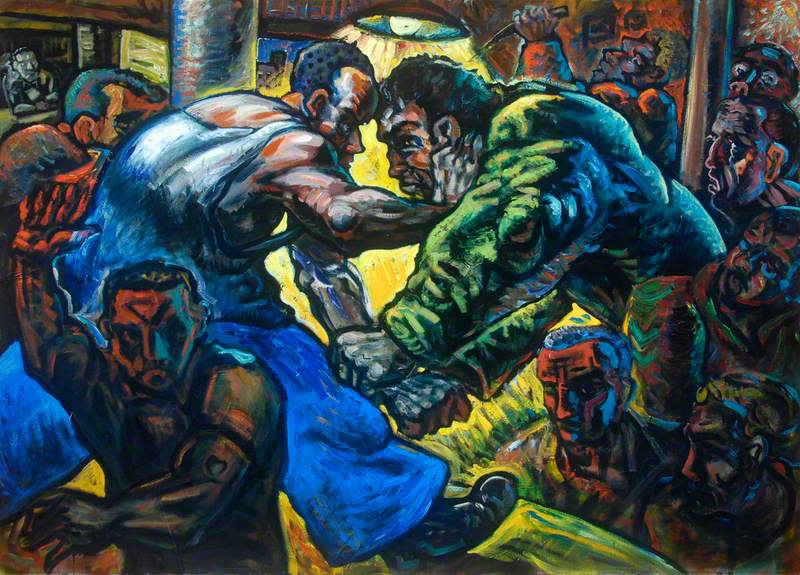

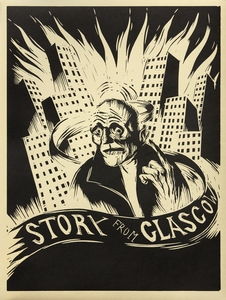

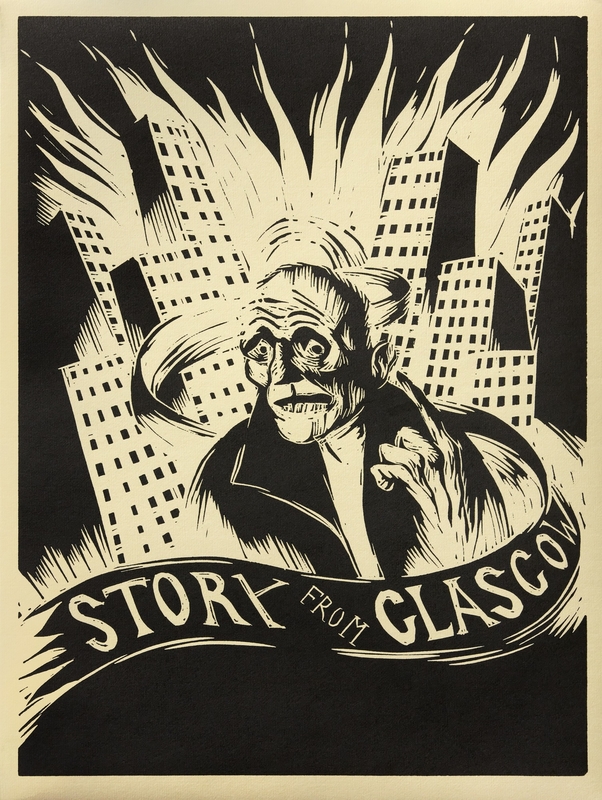

When Currie emerged during the mid-1980s, he was chiefly inspired by Glasgow's industrial heritage and working-class life. Stark works on ink that showed the influence of Expressionist art would continue to form an important part of his practice, especially on themes of industrial decline, such as his 1989 series 'Story from Glasgow'. One of his most impressive works from this time was his Glasgow Triptych, which he explained told 'the story of the Scottish working class in the twentieth century, as reflected in the relationship between an old shop steward and political activist and an unemployed man.'

Story from Glasgow

(bound portfolio of 97 linocuts) 1989

Ken Currie (b.1960)

While the first panel of Glasgow Triptych is a nostalgic look at Labour's 1945 election victory, its neighbour deals with 1980s decay, while the final section shows younger activists planning for the future. In size and subject matter, the triptych shows inspirations ranging from Mexican mural artists, among them Diego Rivera, Fernand Léger, and Germany's New Objectivity movement that featured Otto Dix and George Grosz. With ambitious works such as this, though, he soon became known for his technical prowess and powerful imagery.

In the early 1990s, a notable change came to Currie's style as he was affected by the wars in Eastern Europe, leading him to move from social realist subjects to concerns with death and decayed bodies, as seen in The Troubled City. Gradually the artist moved away from groups to concentrate on individuals, as in his self-portrait Gallowgate Lard, where Currie portrayed himself in thick oils, providing further texture and the macabre sense of real skin through the addition of beeswax. As with many of his portrayals of working-class life, the artist sees existence as a struggle. So it must have come as a surprise in 2001 when the Scottish National Portrait Gallery commissioned a portrait from Currie, an artist not known for working in that genre.

Since it began commissioning in 1982, however, that institution's policy had been to invite artists from outside this field, ranging from Patrick Heron to Currie's GSA contemporaries. Indeed, he was the last of the Pups to be approached, apparently, according to the catalogue for a 2013 exhibition of his work, 'as he seemed the least likely to accept one.' Indeed, the artist originally responded he was unlikely to want to paint 'any of the sitters we might have in mind,' presumably referring to portraiture's traditional focus on established figures.

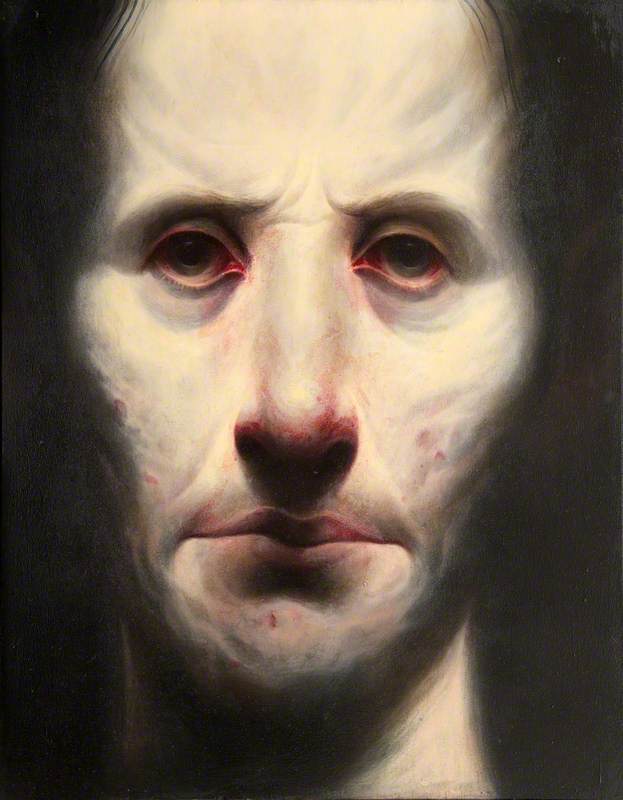

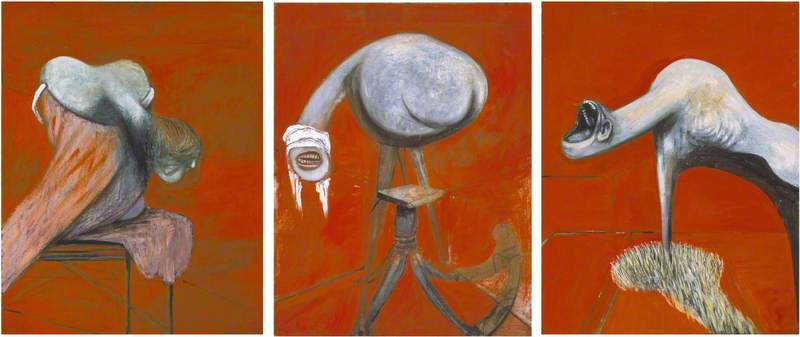

However, Currie swiftly agreed to the gallery's proposal: to portray three men of science, whose concerns went far beyond ego or personal status: Professors R. J. Steele, Sir Alfred Cuschieri and Sir David P. Lane, his Three Oncologists. While the commission chimed with Currie's own humanistic themes, its process was tricky to accomplish. Although his subjects could not spare time to sit for portraits, Currie refused to work from photographs, so life masks were made of their faces.

These uncanny creations are similar to death masks, objects that had featured in Currie's earlier work: his fascination began with viewing one for the notorious Nazi commander Heinrich Himmler at the Imperial War Museum. Between 1995 and 1997 he made a series of paintings based on examples in the University of Edinburgh's anatomy department, among them the artist John James Audubon, the playwright Richard Sheridan and actor David Garrick. Just as Himmler's mask was presented as white on a black velvet background, so these glowing visages emerged from darkness, setting the stage for later works.

Unfamiliar Reflection: Self Portrait by Ken Currie (b.1960)

2006

Ken Currie (b.1960)

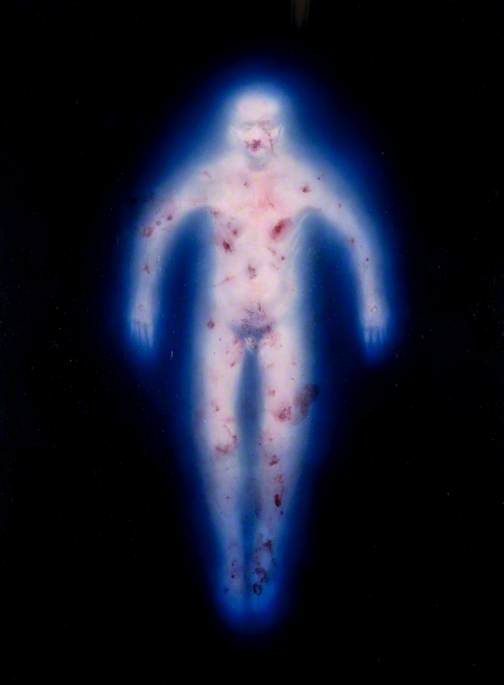

Over the years, the dramatic, large-scale Three Oncologists has become one of the key works in the Edinburgh-based institution's collection. Five years later, it was joined by the self-portrait Unfamiliar Reflection, which Currie painted especially for the gallery's 2007 exhibition 'The Naked Portrait', where it hung beside works by the likes of Lucian Freud and Stanley Spencer. With his body as insubstantial as its mirrored twin, the piece comes across as a meditation on ageing that exudes melancholy and angst. Indeed, Currie revealed that, after completing the work, he was shocked to discover he had painted the face of his recently deceased father, who the artist bore a striking resemblance to.

Las Meninas

1656–1657, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1600)

Elsewhere, the painting references a masterpiece by one of Currie's most revered artists, Velásquez. Hints of the Spanish master's Las Meninas can be found in the use of silky red pigment (another hint at mortality), the mirror and the inclusion of the back of a canvas.

A reflection offers different opportunities in Currie's portrait of Peter Higgs, where the famed Nobel-prize-winning physicist and University of Edinburgh professor, who theorised the Higgs boson particle, is portrayed staring at a light source that could be the result of atoms splitting in the Large Hadron Collider. It is a witty celebration of human ingenuity and a rare sign of positivity for an artist whose work is usually more dour and sombre.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

This content was funded by the PF Charitable Trust