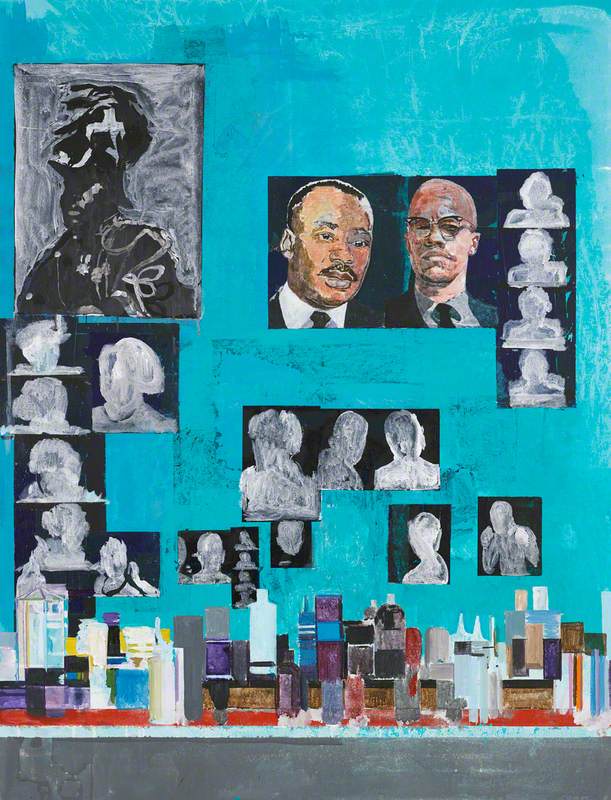

For many years, Black artists have played upon the familiar tropes of Western art to examine its lack of diversity. From Kara Walker's paper cut-out silhouettes to the portraits of Kerry James Marshall, this process has generally focused on subverting figurative art, or portraiture, the latter of which has historically given visibility to white Europeans.

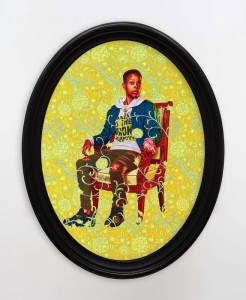

The exhibition 'Kehinde Wiley at The National Gallery: The Prelude' provides a new twist on this process by applying such recontextualisation to the landscapes of the Romantic movement. The American painter Kehinde Wiley was invited by the Gallery to examine its collection and find ways to engage with its classic masterpieces.

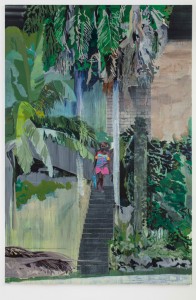

© the artist. Image credit: Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and Galerie Templon, Paris

Production photo from on-location filming in Haiti for 'Narrenschiff' by Kehinde Wiley, 2017

Wiley established himself through representations of Black people in ways that referenced the styles of Old Masters or particular portraits, such as Hans Holbein the younger's The Ambassadors and Jacques Louis David's Napoleon Crossing the Alps. Sometimes he recruited models from the streets, as in Harlem, New York, or important figures posed for him, including President Obama. In London, though, he found himself attracted to the dramatic land and seascapes of the Romantic period, using them as a springboard to devise a series of works that have debuted in his current exhibition.

On show are a set of paintings and one film, all inspired by the movement of European Romanticism that developed alongside changing ideas in thought, music and literature from the late eighteenth century and dominated cultural life for the next 50 years or so.

Romanticism had a particular impact in the field of landscape painting, thanks to a striving for spirituality and a return to nature in the face of growing industrialisation. One of its most famous adherents was Caspar David Friedrich, the German artist representing both these aspects of Romanticism in his work Winter Landscape.

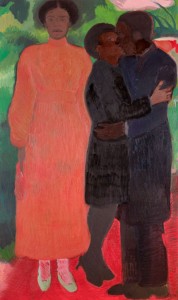

© the artist. Image credit: Kunst Museum Winterthur, Switzerland and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Galerie Templon, Paris

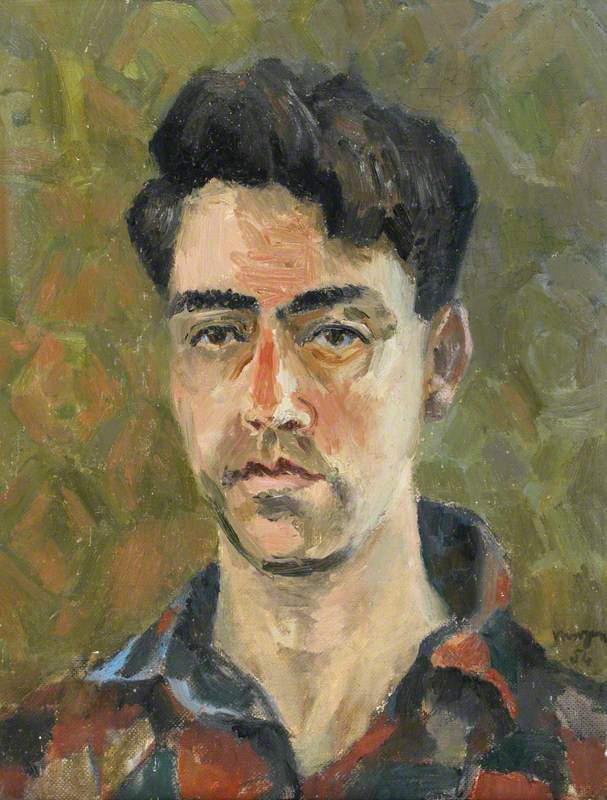

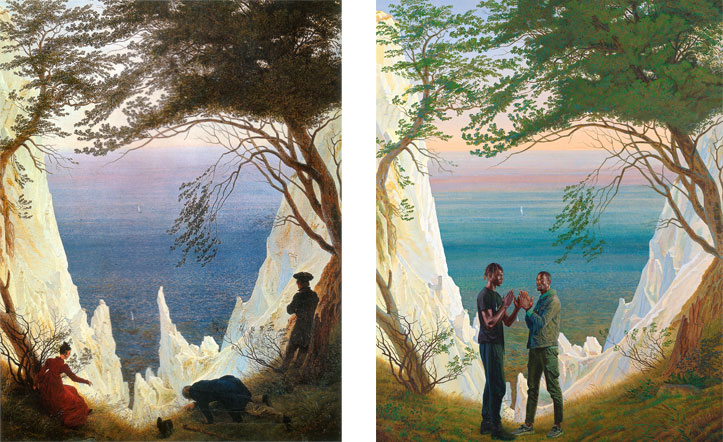

Left: Chalk Cliffs on Rügen, right: Prelude (Ibrahima Ndiaye and El Hadji Malick Gueye)

1818, oil on canvas by Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840); 2021, oil on linen by Kehinde Wiley (b.1977)

For landscape artists, Romanticism called for more expressive representations of grandeur and power that reflected their personal visions rather than accurate representations of views that celebrated land ownership or man's ability to shape the landscape. The Romantic artists were particularly drawn to the wilderness, especially mountain ranges, vistas previously dismissed as too disordered and rough to be worthy of representation. Instead, such rugged, uncultivated scenes represented natural beauty, power and majesty – an effect known as the sublime. Experiencing such environments could be viewed as vital in sparking religious wonder or in terms of providing wisdom and knowledge of the world along with our place within it.

Born in rural North Wales, Richard Wilson was among the first to adapt to these new tastes and became a major influence on the likes of J. M. W. Turner. There was still room for people in these vistas, even if they were simply diminutive figures providing a sense of scale to highlight the immensity on show.

© the artist. Image credit: Hamburger Kunsthalle and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Galerie Templon, Paris

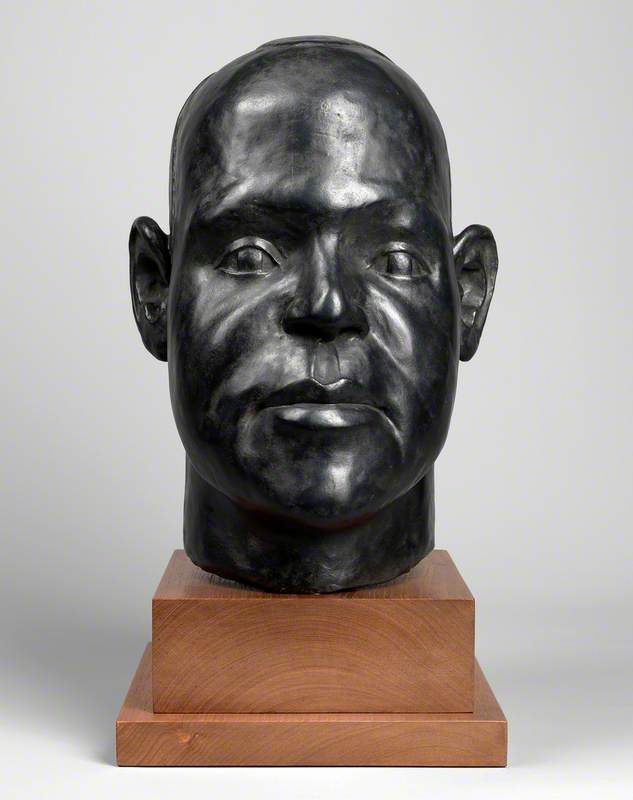

Left: The Wanderer above the Mists, right: Prelude (Babacar Mané)

c.1818, oil on canvas by Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), 2021, oil on linen by Kehinde Wiley (b.1977)

Often, though, these participants helped explore further themes, as in the guise of Friedrich's enigmatic wanderer with his back to the viewer – does he seek solace or wisdom in the wilderness? A group of men, meanwhile, could represent the desire and ability to conquer wild, unpopulated regions – intrepid explorers on an adventure or a group of workers seeking reward for their efforts.

These ideas chime with an earlier set of works where Wiley again approached this period. In 2017 he showed the exhibition 'In Search of the Miraculous' at London's Stephen Friedman Gallery, which concentrated on the genre of Western marine painting, specifically works by artists that worked between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, ranging from the Dutch masters Ludolf Backhuysen I and Willem van de Velde II to the American artist Winslow Homer.

While their original works rarely focus on the human protagonists, it is easy to appreciate Wiley's desire to insert Black characters into these milieus. This was a period when seaborne trade and exploration were vital to the prosperity and power of European nations, as they developed economic links with Africa and then built up empires, notably in the continents of North and South America, including the islands of the Caribbean, leading to the growth of the slave trade.

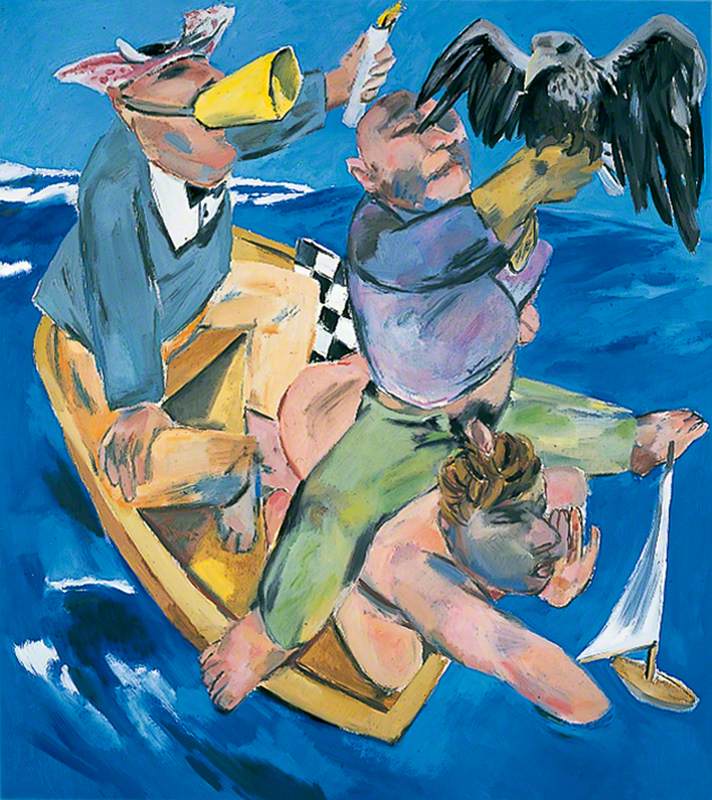

© the artist. Image credit: Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and Galerie Templon, Paris

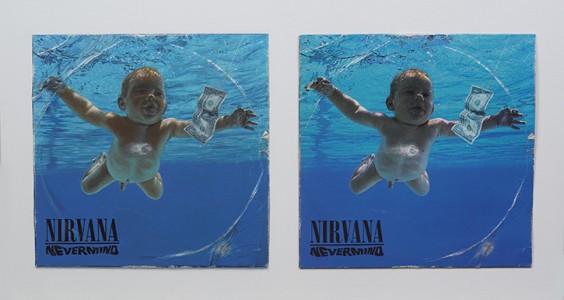

Tempest off a Mountainous Coast (Patrick Laguerre)

2017, oil on canvas by Kehinde Wiley (b.1977)

While the seventeenth-century Dutch School – represented here by Backhuysen – sought to focus on the ability of their homeland's skilful crews and well-built ships in the face of the elements, painters influenced by ideas around the sublime aimed to capture a sense of scale and the power of the elements.

Image credit: Southampton City Art Gallery

Fishermen upon a Lee Shore in Squally Weather 1802

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

Southampton City Art GalleryTurner achieved this with Fishermen Upon a Lee Shore in Squally Weather, a work Wiley expanded on for his sea-focused show. He turned its themes into a triptych, with young men that the artists found in Haiti looking out to sea. His figures, though, were not fishermen but displaced people looking for safety across the water.

In the catalogue for The Prelude, Wiley explains that early on in the development of this exhibition he came to the idea of a polarity between the churning ocean and the seemingly still and pure mountains, specifically those around the Norwegian fjords. 'In terms of metaphors,' he says, 'the ocean becomes a stand-in for the way that we've traditionally viewed the Global South as being the opposite of the rational North.'

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

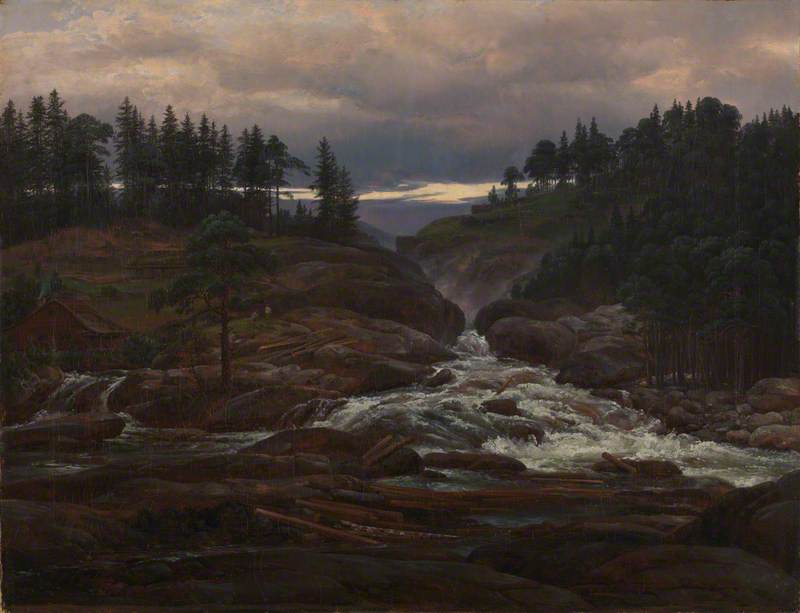

The Lower Falls of the Labrofoss 1827

Johan Christian Clausen Dahl (1788–1857)

The National Gallery, LondonMountain scenes were popularised by the likes of Norwegian artist Johan Christian Dahl, who would regularly travel around his native land to celebrate its beauty, as with his portrayal of one of Norway's most important waterfalls. Dahl was a friend of Friedrich, though focused less on spiritual intensity than attention to detail.

© the artist. Image credit: Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and Galerie Templon, Paris

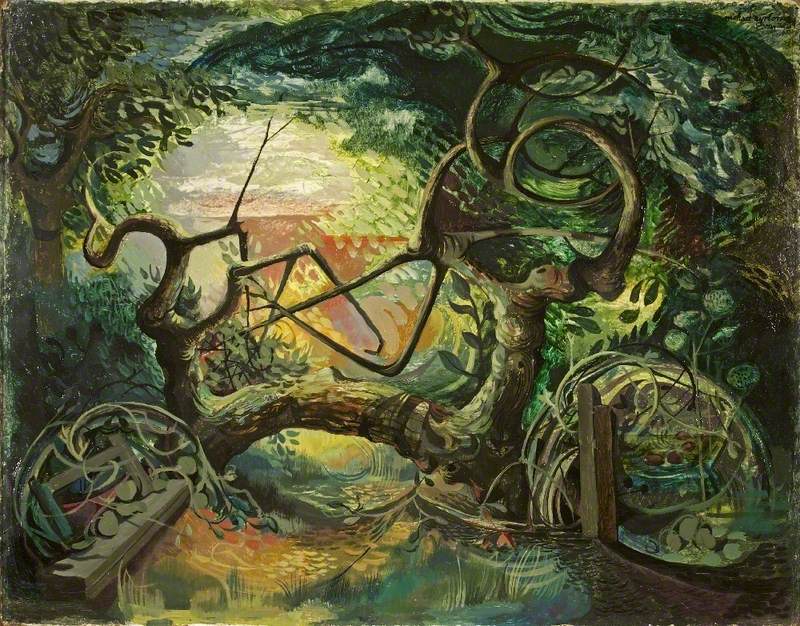

Still from 'Prelude'

2021, film still by Kehinde Wiley (b.1977)

Wiley recognises how mountains represent a range of values. As some of the highest and inaccessible points on Earth, they portray purity and godliness, though that comes with the sense that they throw down a challenge to inquisitive and brave men – those heights are there to be attained, to be conquered. The artist also admits he is attuned to the importance of the colour white, especially when it envelops Black figures, as seen in his film Prelude.

© the artist. Image credit: Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery, London, and Galerie Templon, Paris

Production photo from on-location filming in Norway for 'Prelude' by Kehinde Wiley, 2020

He explains: 'The sheer irrational domination that it holds over the body within that pictorial plane has a direct and indexical relationship to my emotional response to American white supremacy and the impossibility of escape from it.'

© the artist. Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Production photo from on-location filming in Haiti for 'Narrenschiff' by Kehinde Wiley, 2017

In his response to Romanticism, Wiley places the human figure – and the Black figure – centre stage. By sharing his perspective, he demonstrates what artists of the Romantic movement ignored, while helping contemporary viewers to appreciate what we often miss.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Kehinde Wiley at the National Gallery: The Prelude' runs until 18th April 2022