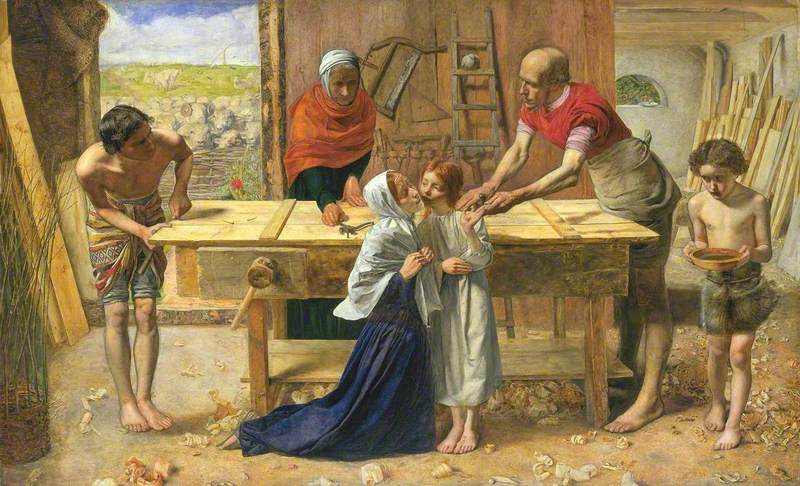

In 1860, ten years after Charles Dickens published a scathing review of Pre-Raphaelitism in his magazine Household Words, John Everett Millais exhibited what would become one of his most famous paintings. The Black Brunswicker depicts a young Englishwoman making a futile attempt to prevent her Prussian fiancé from fighting in the Battle

For many of the spectators who flocked to see Millais’ latest masterpiece, a major attraction was the chance to see the model. The young woman in the striking silk

Millais wrote to his wife, Effie, that it was 'the most satisfactory work' he had exhibited so far. As well as the famous version now at the Lady Lever Art Gallery, there are several studies for the painting in the Tate, and this version, now at the Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture, was completed by Millais' brother William.

Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

John Everett Millais (1829–1896) and William Henry Millais (1828–1899)

Royal Scottish Academy of Art & ArchitectureAt the time of

'I made your father’s acquaintance when I was quite a young girl. Very soon after our first

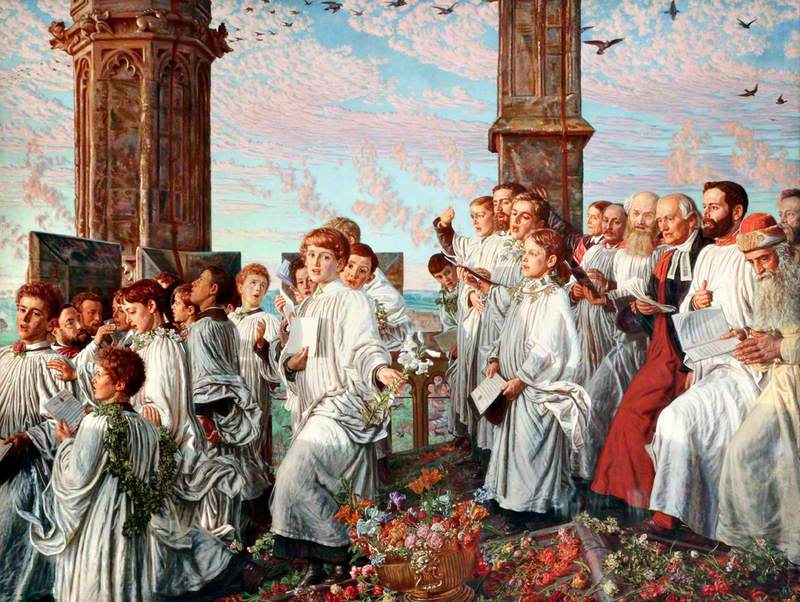

Image credit: Charles Dickens Museum, London

Katey Dickens (1839–1929) 1860s

Charles Allston Collins (1828–1873) (attributed to)

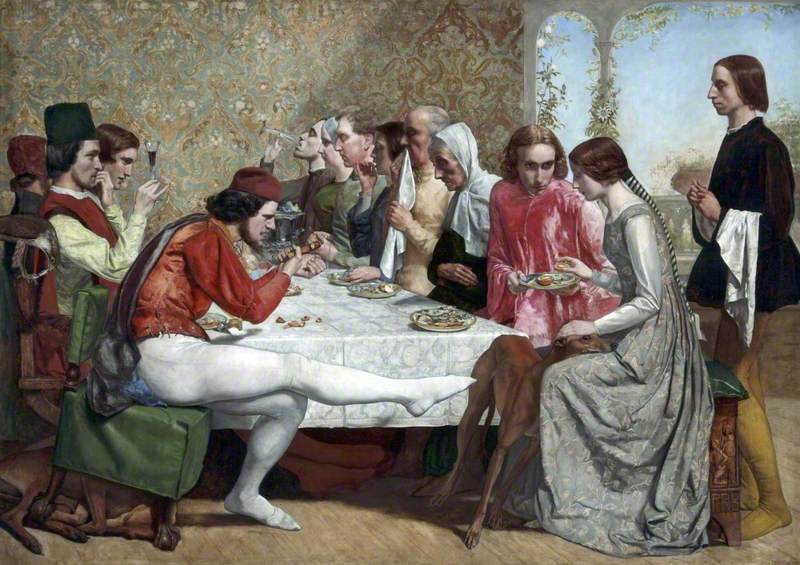

Charles Dickens Museum, LondonKatey Dickens and Charlie Collins were married in 1860, the same year in which The Black Brunswicker was first seen by the public. Charlie was one of the artists whose careers had been blighted by Charles Dickens’ article, ‘Old Lamps for New Ones’. Although many artists never forgave Dickens for his scathing words, Millais had long forgiven him and, by 1860, Dickens counted the young artist amongst his friends. Many years later, in an article about her father, Katey revealed that Dickens had felt guilty about the consequences of his article; he had not foreseen how seriously people would take what he had intended to be

In 1874, Millais began another painting of Katey, who had been widowed and was marrying for the second time. Her first marriage was not a success in the conventional sense; she told her father Charlie 'ought never to have married', and a family friend wrote furiously to his wife 'It is an infamy that Charlie Collins has taken a wife'. It seems Charlie was gay, something he could not have admitted in Queen Victoria’s Britain. When writing Katey’s biography, I came to the opinion that Charlie was unrequitedly in love with Millais. Katey and Charlie’s marriage was never consummated, so, of course, there were no children, but within a few years they had become very close companions. Charlie, it seems, was aware of his wife’s long-term affair with fellow Pre-Raphaelite Valentine Prinsep. Theirs was not actually an entirely unusual marriage for a Victorian couple; it was just not the kind of marriage that makes it into Victorian novels.

Throughout their marriage, Charlie suffered from a mysterious illness. It was many years before he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. Katey cared for him tirelessly, which meant her career had to be placed on hold. She nursed him and ran their household on a surprisingly limited budget – too proud to tell her doting father how little money they had. They couldn’t even afford a maid, something truly shocking in the nineteenth century. As a result, very little artwork survives under the name 'Kate Collins'.

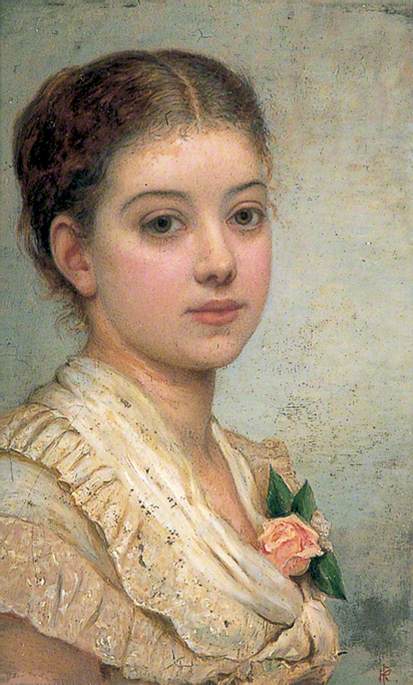

The second time Millais painted Katey, he painted her portrait as a wedding present for her second husband (who had also become a friend of his). After Charlie Collins died in 1873, Valentine Prinsep proposed to Katey with almost indecent haste. To his surprise, she refused him. She also refused a proposal from another Pre-Raphaelite, Fred Walker. This is because she had met and fallen in love with the artist Carlo Perugini, whom she almost certainly met at Lord Leighton’s house.

Image credit: Charles Dickens Museum, London

Katie Perugini, née Dickens (1839–1929) 1873–1875

Charles Edward Perugini (1839–1918)

Charles Dickens Museum, LondonCarlo was one of Leighton’s friends and studio

After her baby’s death, Katey threw herself back into her work and within a short time was being accepted to exhibit at the Royal Academy. She exhibited under the name Kate Perugini and signed her works with an intertwined 'K' and 'P'. In addition to the RA, she exhibited at the Institute of Water Colour Painters, the Society of Lady Artists, the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly and at exhibitions and galleries overseas, including the famous World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Katey and Carlo shared a large joint studio, which they created in their home, and at which they would hold parties and exhibitions.

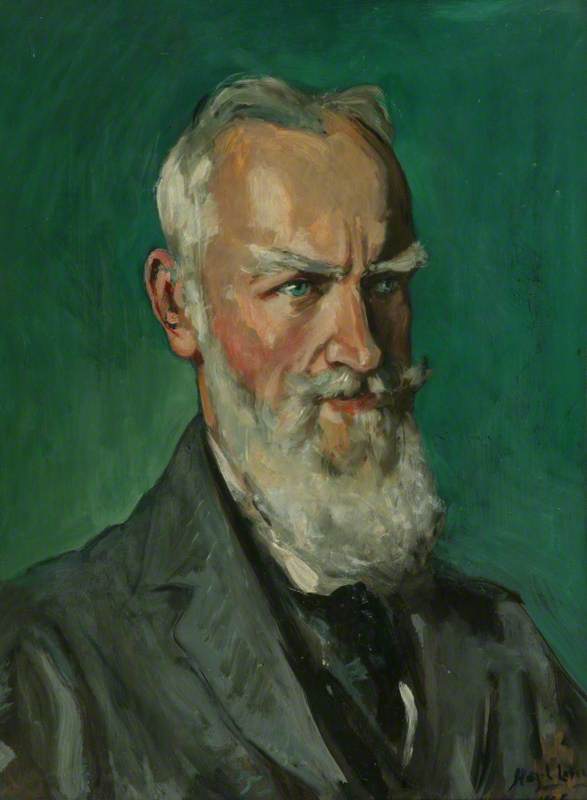

Image credit: Guildhall Museum, Rochester

Mary Angela Dickens (1862–1948) (granddaughter of Charles Dickens) 1882

Kate Perugini (1839–1929)

Guildhall Museum, RochesterThe portrait Millais began in 1874 was, according to its provenance, largely dictated by the model. Katey chose to wear a black dress made partly from a provocatively sheer material. She was in mourning for Charlie, but she also liked wearing black, considering it very flattering, so she wore it deliberately. Allegedly she positioned herself with her back to Millais, looked over at him one shoulder and said, 'This is how I wish to be painted'. Uncharacteristically, Millais agreed to let her dictate the

The portrait was widely praised when it was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery, the home of Aestheticism. Katey was an integral part of Aesthetic London, and friends with all the most important artists and bohemians of the day. Despite this praise, there was one person who was never satisfied with it: John Everett Millais. He worked on it for six years, before he admitted defeat. He was a regular visitor to the

Lucinda Hawksley, author

Katey is Lucinda's great-great-great aunt. Lucinda is descended from Katey's brother Henry Fielding Dickens.

Lucinda Hawksley’s new book Charles Dickens and his Circle is published by the National Portrait Gallery. Her biography of Kate Perugini was published by Doubleday. To find out more, visit www.lucindahawksley.com or find Lucinda on Twitter @lucindahawksley