In the largest retrospective since the artist's death, Towner Eastbourne's show 'John Nash: The Landscape of Love and Solace' has drawn on works from the major national collections, 29 regional galleries and 38 private lenders to showcase an artist whose breadth and significance has been long overlooked.

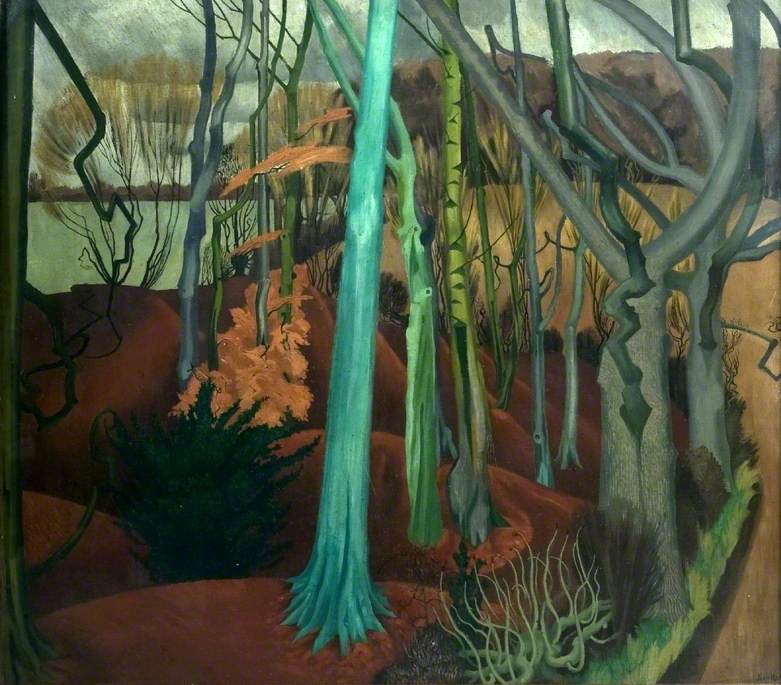

The Rainstorm

by John Northcote Nash (1893–1977)

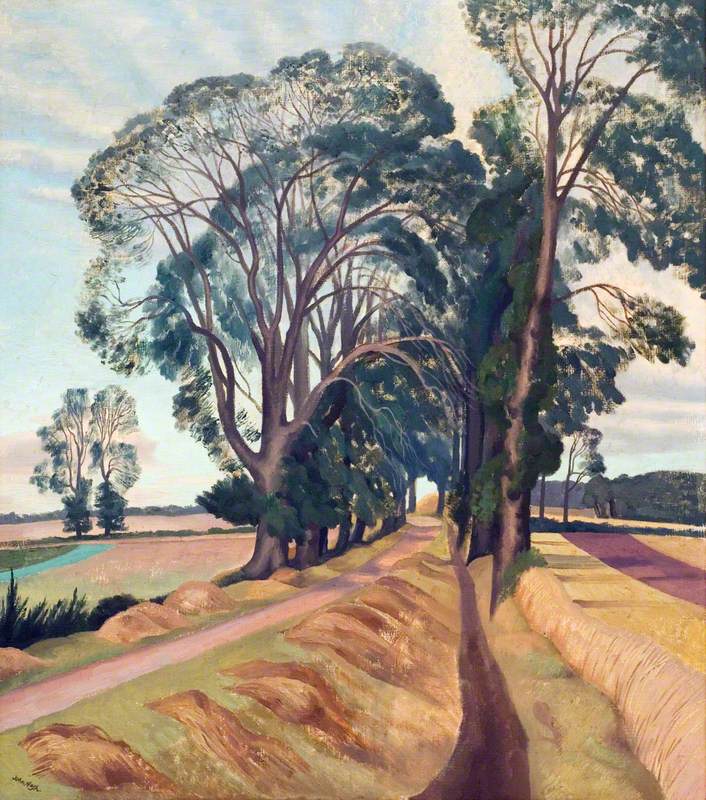

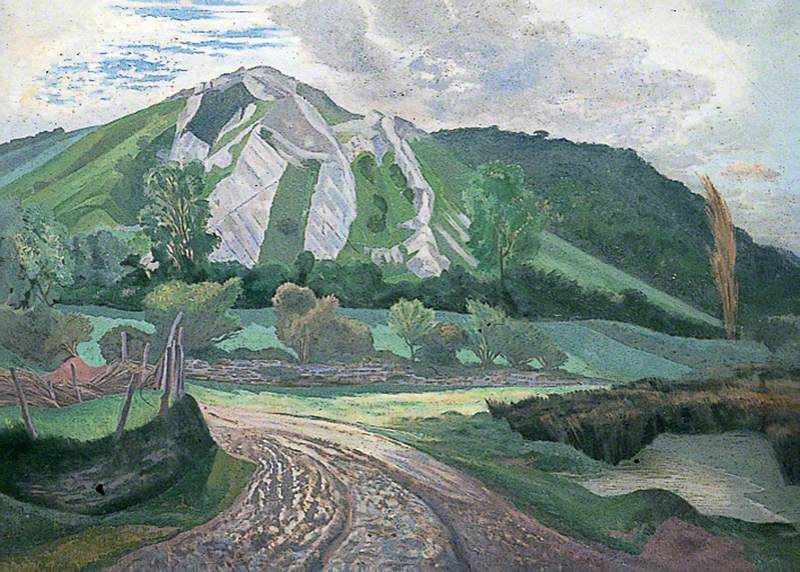

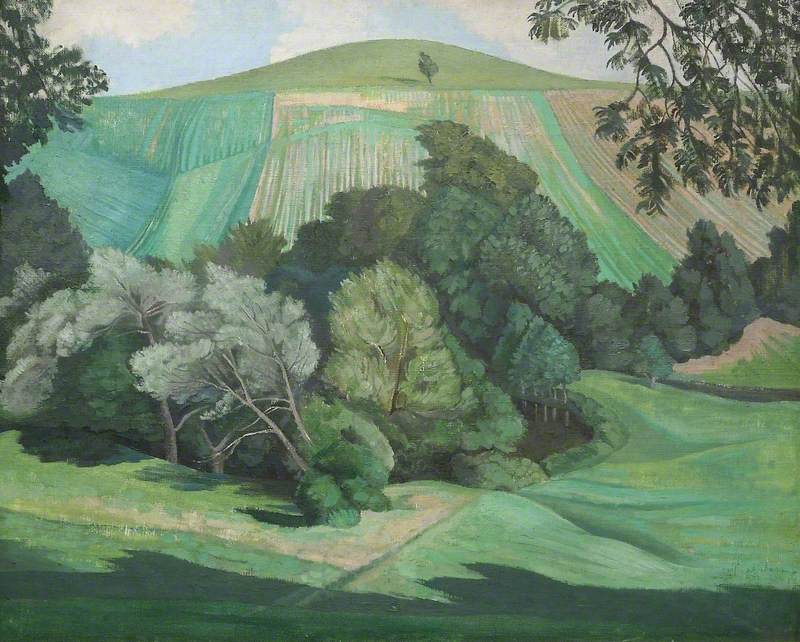

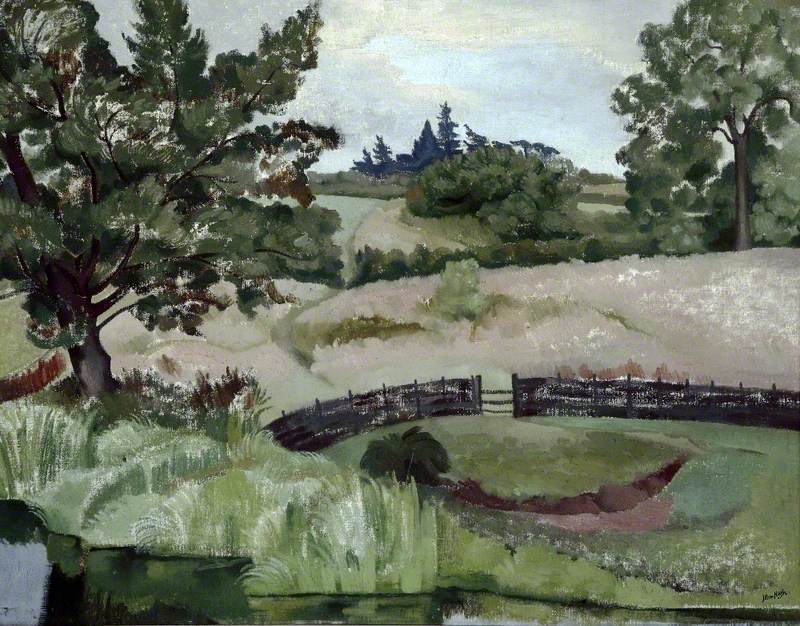

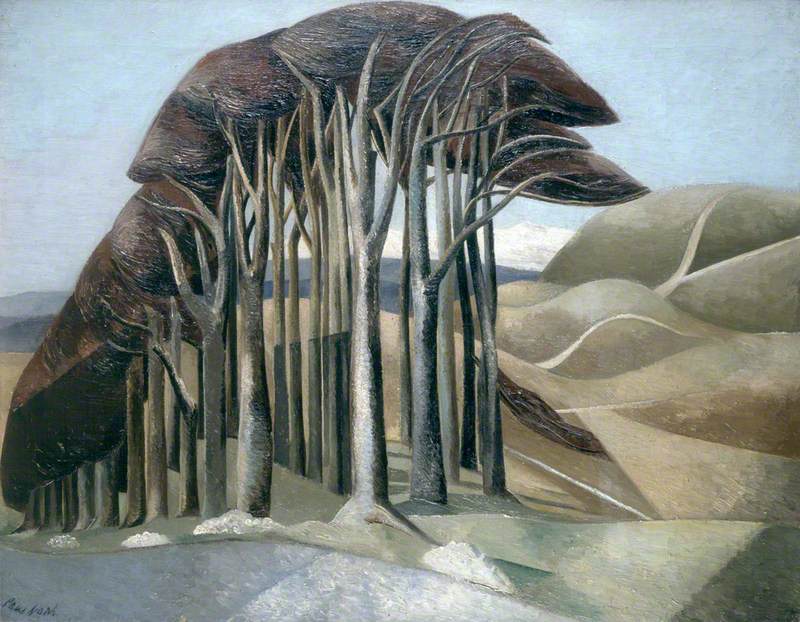

It is 54 years since the Royal Academy honoured John Northcote Nash (1893–1977), one of its longest-serving members, with a sprawling exhibition that gathered works from across six decades. As a painter, wood engraver, lithographer and illustrator, Nash's oeuvre centred on observation and love of the natural world and immersion in all things rural.

Occupying the main Royal Academy gallery spaces during the summer of 1967, it was a singular honour for Paul Nash's industrious and distinctively accomplished younger brother, who, then aged 73, still had a decade of painting and exhibiting ahead of him. But it was also an event at odds with the broader visual culture of the 1960s in which Pop Art's derivations and brash abstraction held sway.

While Nash's oil paintings of woods and cornfields, watercolour snowscapes, comic book illustrations and minutely observed botanical studies graced the Academy walls, the world beyond Piccadilly was beset by industrial strife. Northern Ireland was primed to explode and San Francisco's summer of love had already given way to the napalm of Vietnam.

Emotionally out-of-kilter with the times, Nash's achievement struck many exhibition-goers in 1967 as a rural by-way anchored in England's artistic past, his endeavour irrelevant to the zeitgeist. More than half a century later, however, as our second pandemic summer unfolds, visitor responses to 'John Nash – the Landscape of Love and Solace' suggest the very opposite. Both the artist's life story, punctuated by unexpected trauma and sudden loss, and his art, celebratory and melancholic by turns in response to nature's succour, seem appropriately of the moment, speaking afresh to our collective experience.

The exhibition's title has triple intent. First and most obviously it references Nash's love of being in and moving through landscape. As a young child he was given a late Victorian I-spy book and ever after a country walk with John Nash was apparently a revelation: things previously unseen were noticed, over-familiar things were seen afresh, visual notes were made. As he said at the end of his life: 'the artist's main business is to train the eye to see, then to probe and then to train his hand to work in sympathy his eye. I have made a habit of looking, of really seeing'.

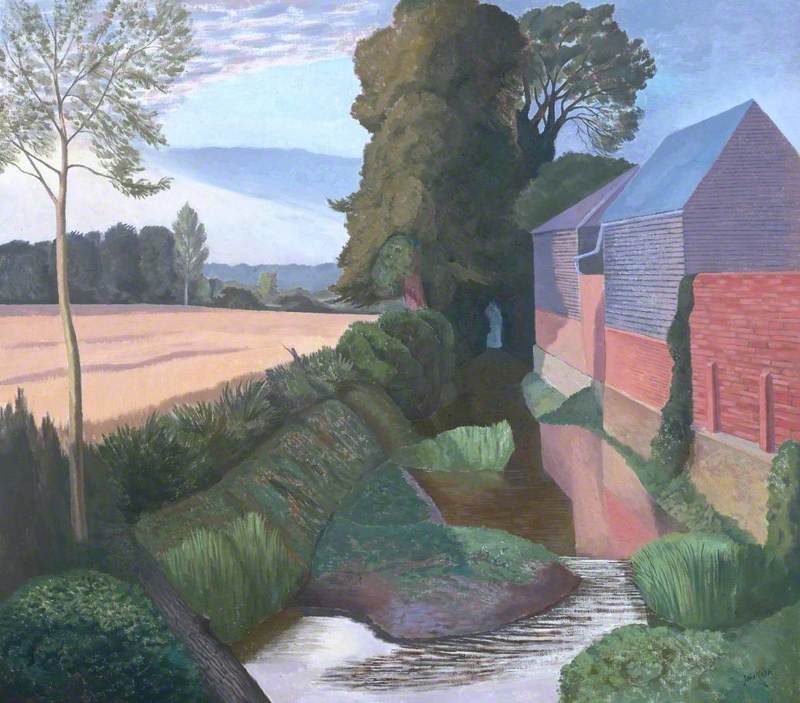

Nash was attracted to the nooks and crannies of the rural scene. As he said to John Rothenstein, half a haystack interested him as much as a mountain range, and half of his best works can be traced to locations within walking distance of his long-term homes in the Chilterns and the Stour Valley.

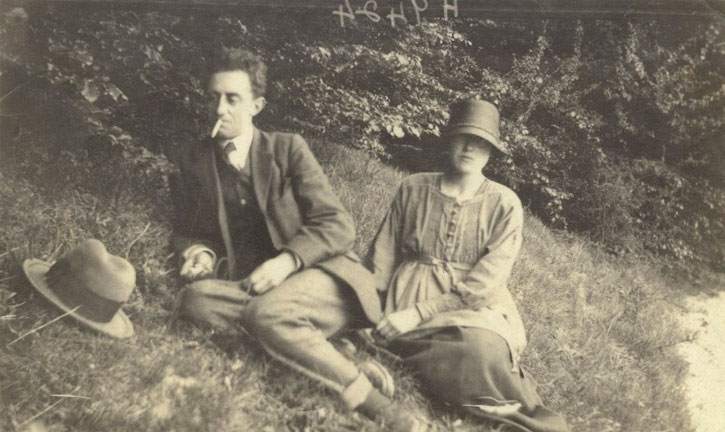

Secondly, the landscape of love refers to the complex, shifting web of affairs and relationships that accompanied his endeavours. The remarkable Christine Kuhlenthal, a Slade student and intimate friend of Dora Carrington, became his lover just before he departed to the trenches in late 1916.

John Nash and Christine Kühlenthal

1920, photograph by unknown artist

They pledged to marry if he returned alive, but their deep commitment to each other would not exclude either having 'outside loves'. Their own love endured for sixty years, surviving numerous crises and periods of distance, and an ongoing dichotomy between Christine's pursuit of intimacy and John's more libertine habits. It was an extraordinary partnership, during which Christine's harvesting of scant resources and organisation of John's artistic calendar (of expeditionary activity, work at home, and exhibiting) rendered possible her husband's long career.

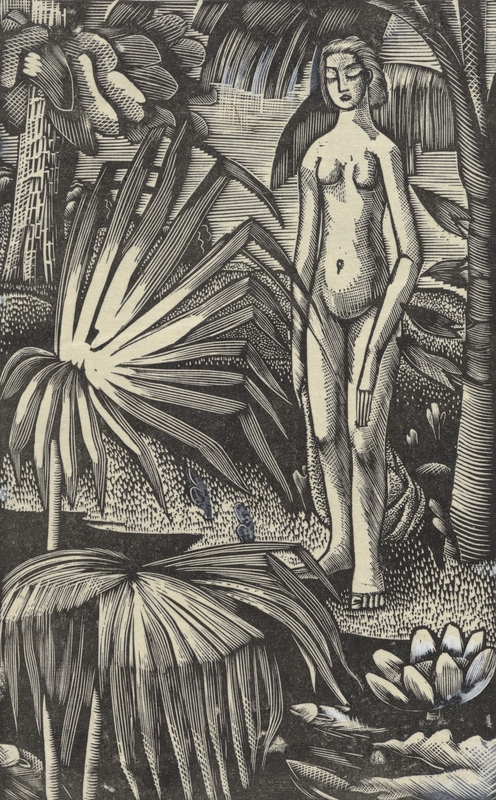

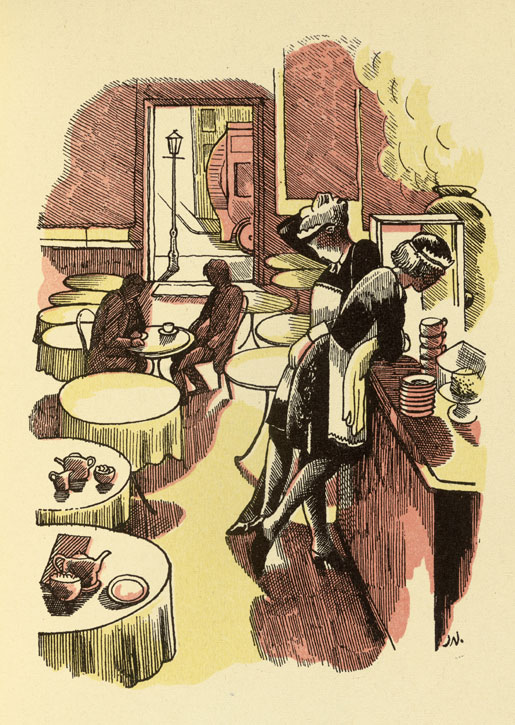

Illustration for Walter de La Mere’s short story

1931, line drawing with stencilled colour by John Northcote Nash (1893–1977)

Thirdly, the notion of a landscape of solace – or a search for solace in the external landscape – relates to the emotional wellspring of Nash's artistic endeavour as a painter who was not only beset by periodic mental distress (a familial trait shared with his brother Paul and younger sister Barbara) but who, in the course of a long life, encountered more than his fair share of trauma and loss.

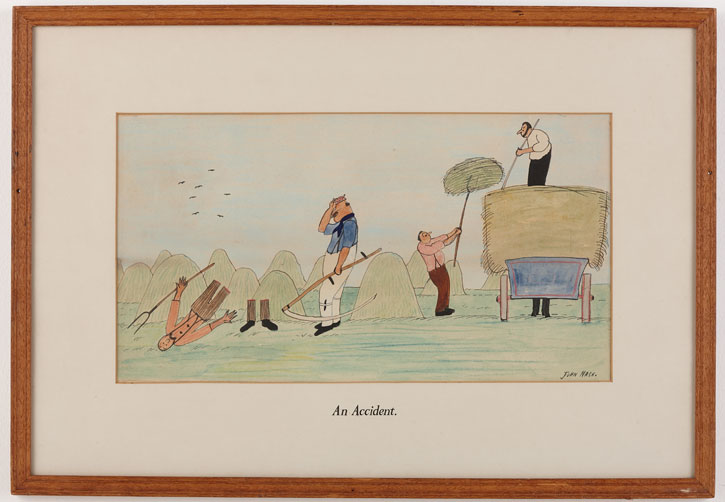

John's childhood was overshadowed by his mother's mental decline and early death in a private sanatorium and his earliest artwork survives in the form of marginal cartoons leavening letters to his frequently absent parents. Absorbing the influence of Edward Lear, his cartooning flowered – and lead to many of his early book commissions – but as Christine quickly discerned, humorous endeavour for the young John was 'a useful cloak'.

An Accident

1912, chalk ink & wash on paper by John Northcote Nash (1893–1977)

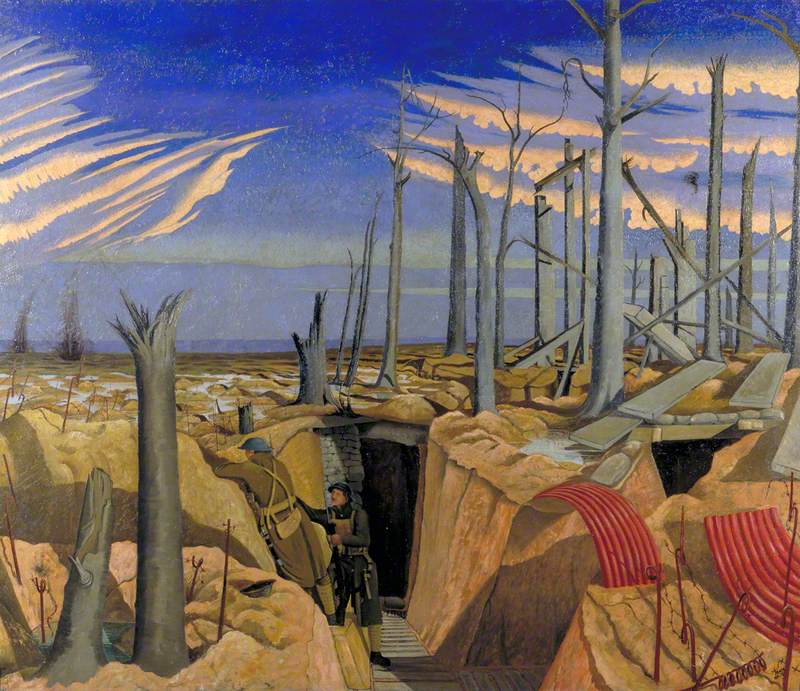

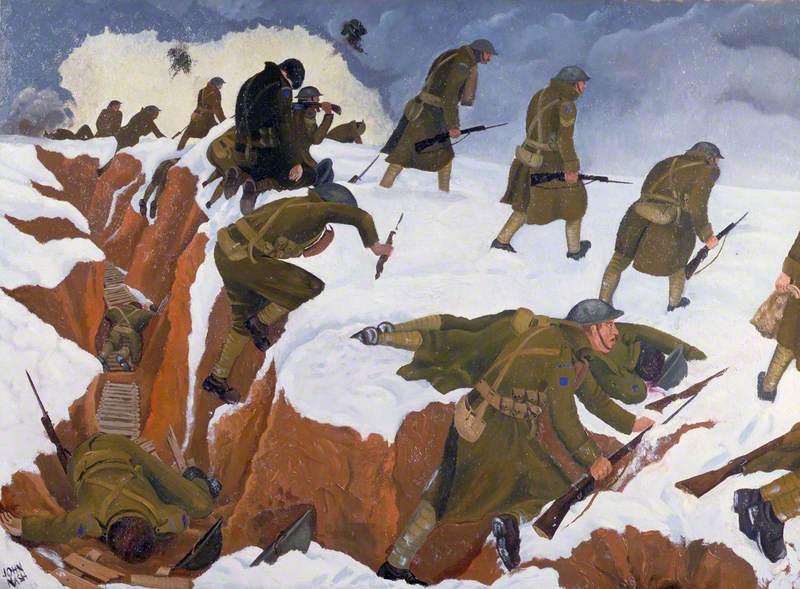

Nash endured 15 months in France as a lowly 'ranker' in the Artists' Rifles before being granted leave after a disastrous counter-attack in which nearly all his close comrades died in the space of 20 minutes at Marcoing on the morning of 30th December 1917. Back in England, he succeeded in getting appointed as an Official War Artist, but previously forbidden to draw in the trenches, he then had to create war art from his formidable powers of recall.

In Oppy Wood he memorialised his first days in the trenches, but also affirmed his faith in a benign natural order removed from man's destructiveness (in contrast to Paul's vision of a universe entire in its evil expressed in The Menin Road).

However, his most telling painting Over the Top was a homage to his fallen comrades at Marcoing; rendered in a restrained malevolent palette, it is a painting in which every element of design reinforces a sense of unfolding tragedy. It would become the signature image of 'The Nation's War Art' at Burlington House in 1919, praised for its authenticity by those who had endured the sorrow and the pity of the Western Front. For Nash its creation was purgative, although his distress at 'the sheer bloody murder' he had witnessed never totally left him. What is remarkable is that while he was working on it by day, he was also leaving the studio in the evening, reacquainting himself with surrounding Buckinghamshire as he painted The Cornfield – a work created 'in sheer relief at being still alive and back in the English countryside'.

'Over The Top': First Artists Rifles at Marcoing, 30 December 1917

1918

John Northcote Nash (1893–1977)

A third traumatic event occurred on 13th November 1935. A year later, while learning auto-lithography at the Curwen Press, his diary simply read: 'Anniversary of the worst day of my life – glad to be working hard to forget'. The event he was referring to was the death of William, his and Christine's only child, who, after being collected from nursery, had fallen from the car she was driving.

Following the tragedy were years in which sadness coloured all their days. In 1939, with the wider cataclysm of a return to war, John became an official war artist once again.

Deadly Nightshade from ‘Poisonous Plants – Deadly, Dangerous and Suspect’

1927, wood engraving by John Northcote Nash (1893–1977)

Nash's three principal areas of endeavour were as artist and illustrator, as a passionate gardener from childhood and as a musician (when together, he and Christine played piano duets daily). In all these areas he was largely self-taught (never attending an art school, horticultural or music college as a student) but always ready to absorb the influence of others. The artist-musician Rupert Lee inspired him to read music, the nurseryman Clarence Elliot was both a close friend and plant-world royalty who gained him entrée to judging at Chelsea. But in terms of his art what is most noticeable – as in his progress as a wood engraver from novice to leading exponent in a matter of four months after August 1919 – is the degree to which, once seized, he could immerse himself in new media to such telling effect.

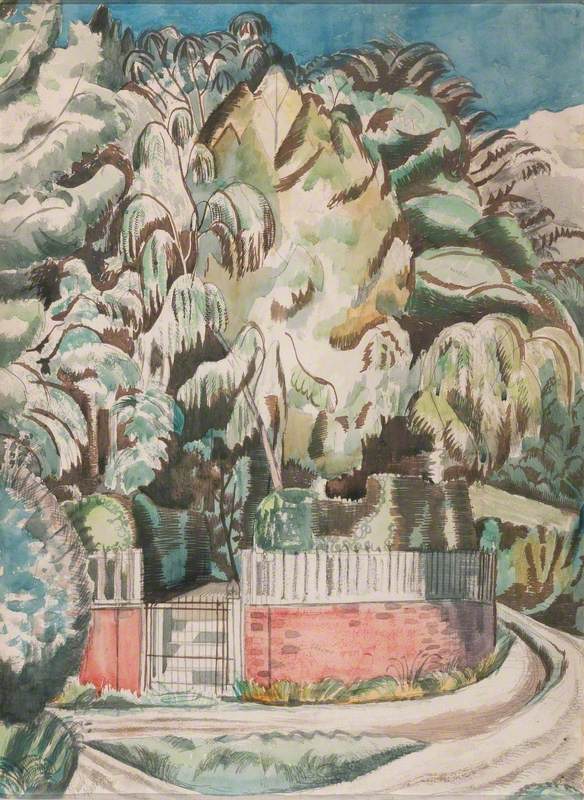

The Villa Next Door

1975, watercolour & pencil by John Northcote Nash (1893–1977)

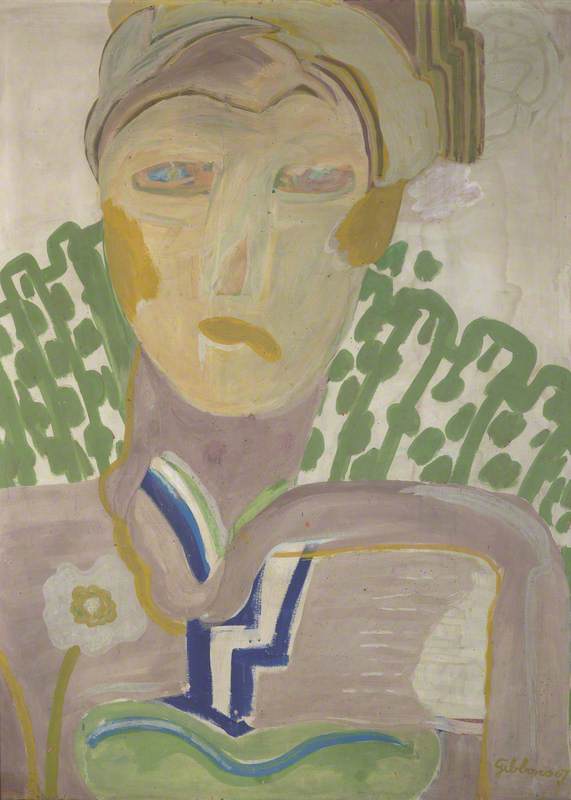

Critics and art historians have sometimes cast Nash as a figure who was disinterested in art, largely ignorant of other's work and someone whose long career consequently lacked breadth and variety. It is true that Nash had little time for metropolitan pretension or the obscurities of the contemporary art scene. But the current retrospective thankfully disabuses us of the notion of aesthetic autarchy, showing, for example how Walter Sickert was an early influence, and how Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman and Robert Bevan ('the Cumbers Men') were central to his progress in oils after he burst onto the London art scene with an impromptu exhibition in December 1913.

The exhibition also reveals how the followers of Cézanne, and specifically Jean Marchand, influenced Nash's development as a painter in the 1920s. His friendship and collaboration with Edward Bawden in the 1950s, and Peter Coker in the 1970s also triggered new departures; and figures as diverse as the 1920s etcher Francis Unwin, Eric Ravilious before 1942, Carel Weight in the 1950s, and Cedric Morris in the 1960s were comrades in art as well as friends who to him were 'dear ones'.

These painters are each represented in the exhibition by one or two salient works – a feature that helps to highlight Nash's own development over time. Nash earned his living influenced by other artists, sometimes advancing, sometimes retreating in confidence under the impact of personal events, but always pursuing a personal practice that never tried to capture more than existed in the natural world. That having been said, Nash admitted he was frequently taken by surprise by the reality he observed, and it is this sense of innocent wonder suffused with melancholy that distinguishes his art at its best, resonating with the solace that many of us might seek out of doors in a season of stress.

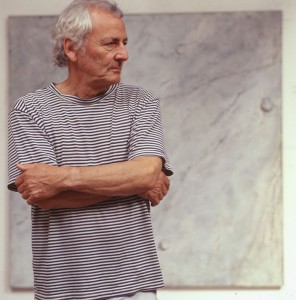

Andy Friend, curator of 'John Nash: the Landscape of Love and Solace'

'John Nash – The Landscape of Love and Solace' is at Towner Eastbourne until 26th September 2021. An accompanying biography John Nash - The Landscape of Love and Solace by Andy Friend, with an introduction by David Dimbleby, is published by Thames & Hudson