In 1857, the renowned writer Frances Power Cobbe visited Rome – a bustling artists' colony full of pioneering painters and sculptors – where she met Welsh sculptor John Gibson. She described him as 'a most interesting person; an old Greek soul, born by hap-hazard in a Welsh village.'

Cobbe was introduced to John Gibson by the American actor Charlotte Cushman, the matriarch of a group of women artists who today would probably be identified as lesbians. In this group was the Welsh sculptor Mary Lloyd, who would become Cobbe's partner and Gibson's pupil. Although he rarely took pupils, he made an exception for his fellow countywoman, and the American sculptor Harriet Hosmer.

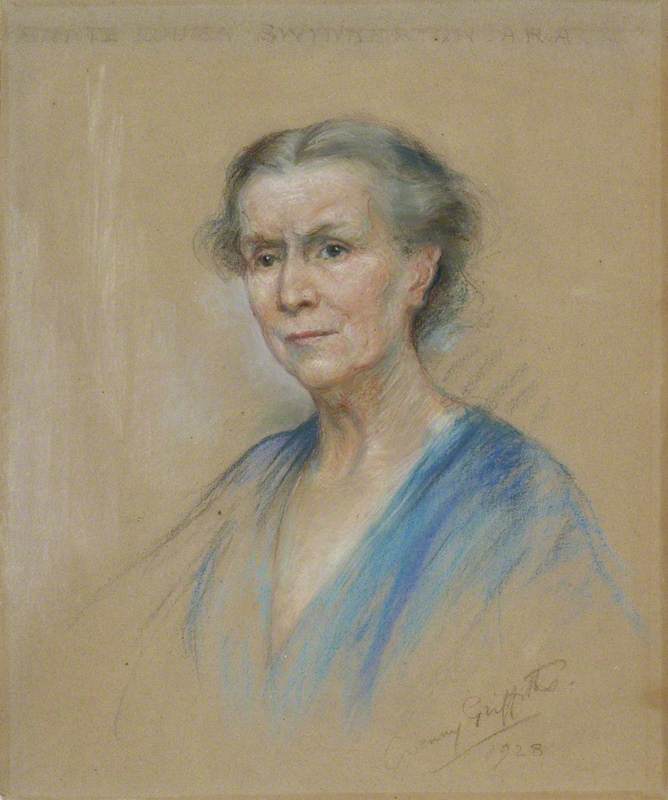

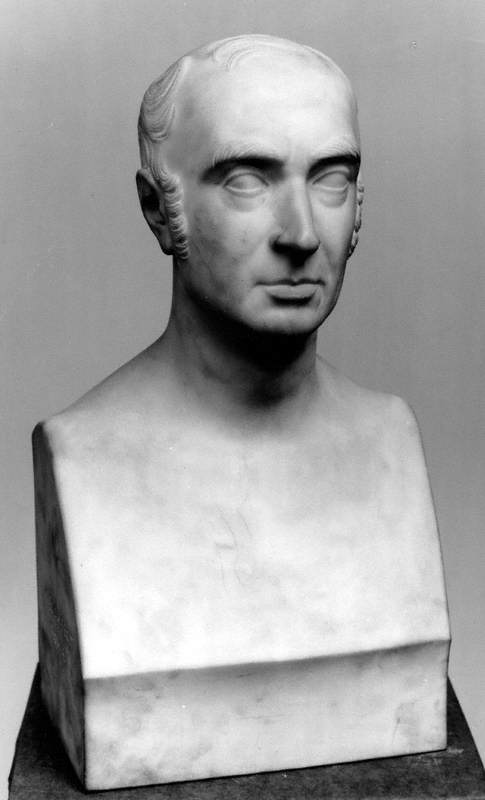

It was these women who helped Lady Elizabeth Eastlake write her posthumous biography of John Gibson, with whom she had been friends for many years. He had sculpted her husband, Lord Eastlake.

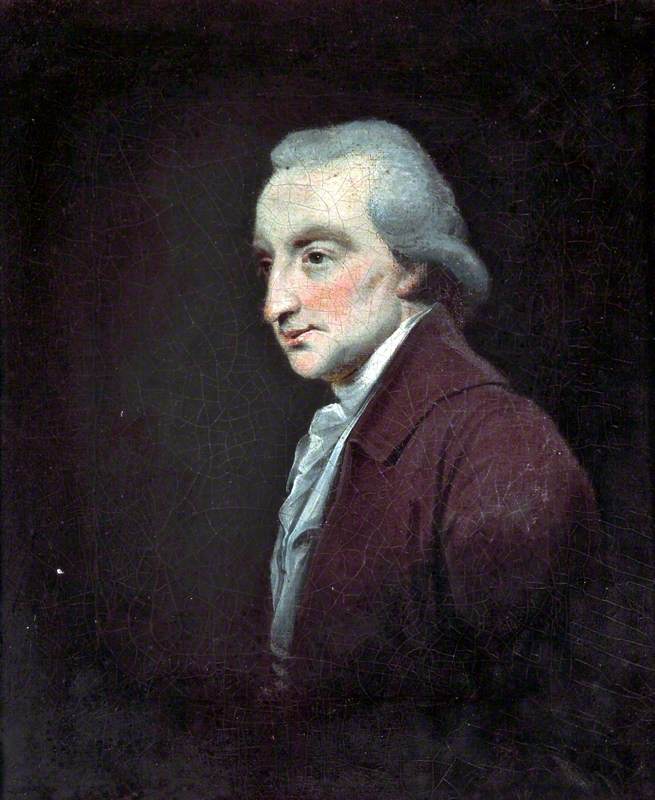

Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (1793–1865)

1840

John Gibson (1790–1866)

John Gibson was born in a small cottage in a small village – Gyffin, near Conwy in north Wales – to a modest, Welsh-speaking family. His father was a market gardener: a humble beginning for someone who was to become famous in his lifetime, and whose clients came from the highest echelons of society. Describing his early life, John said:

'My father and mother were Welsh, and it was Welsh we spoke always. Speaking English was a labour to us. My father was a poor man, truly honest; my mother was an excellent woman, passionate and strongminded; she ruled my father always, and continued to govern us all as long as she lived. I owe much to my mother's early instruction in truth and honesty.'

Moving to Liverpool, John first became a wood carver but having met a sculptor in marble whose 'works enchanted me' and, having emancipated himself from his apprenticeship, he was later noticed by William Roscoe, who became his first patron.

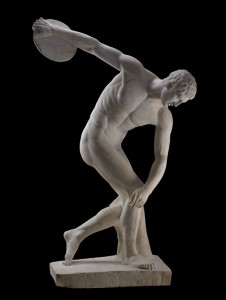

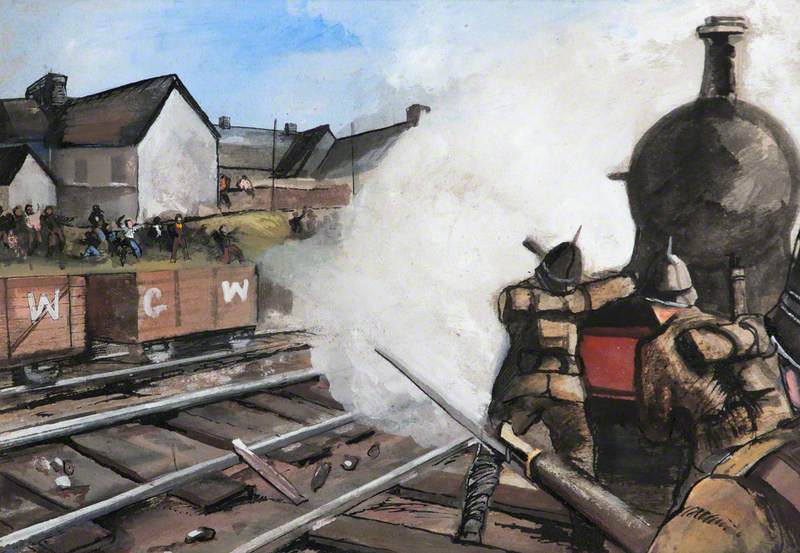

From this time on, John flourished as an artist under the guidance of Roscoe. His first great success was a bassorilievo, Psyche Carried by the Zephyrs, sent to the Royal Academy, where John Flaxman praised it. Still, John was restless and believed his future lay in Rome where several great sculptors were living. He moved there, and gained the patronage of Antonio Canova, one of the greatest Neoclassical artists. John's first marble was Sleeping Shepherd Boy (1824) and from then his fame steadily grew until he was simply known as 'Gibson of Rome.'

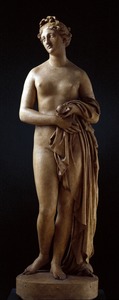

His most controversial piece was Tinted Venus. John believed, rightly, that classical statuary had been coloured and so painted Venus in flesh colours – an act which shocked Victorian society. A naked woman in pristine white marble was art; a naked woman in flesh tones was simply rude.

In Rome, John was extremely close to Welsh artist Penry Williams, who was born in Merthyr Tydfil but moved to Rome in 1827 where he led a flourishing studio. Today, it is widely believed that John and Penry were in a same-sex relationship, although historical circumstance makes it challenging to definitively prove. The word 'queer' – denoting sexualities or gender identities that do not conform to heteronormativity – is often used as an umbrella term to address these difficulties and to avoid the challenges of rapidly changing terminologies.

One difficulty in identifying historic same-sex couples is the frequent destruction of evidence due to homosexuality being previously illegal. Therefore, it has been necessary to construct a set of criteria that can help define the nature of relationships – for example, people who remain unmarried and have no children, which applies to both John and Penry. This is not proof in itself, but a strand of the criteria that, when added together, provides more convincing circumstantial evidence.

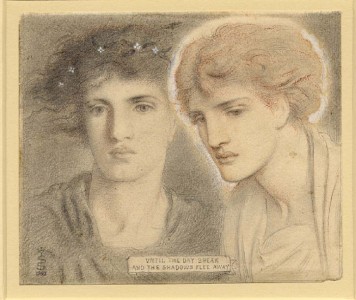

The Bay of Naples Seen from the Scalinata Petraio

1830s

Penry Williams (1802–1885)

For almost 40 years, the men's names were linked, often in the use of 'couple speak': narratives – by the couple or others – that tie two people together. Neither John nor Penry left extensive archives – an additional indication of a same-sex couple is that they often destroy their archives – however, some letters exist in the Royal Academy of Arts Archive and 'couple speak' can be seen in many of these. For example, friends and family writing to John would often send acknowledgements to Penry, such as artists Caroline Tilghman and Benjamin Gibson, John's brother, who wished to be 'remembered' to Penry.

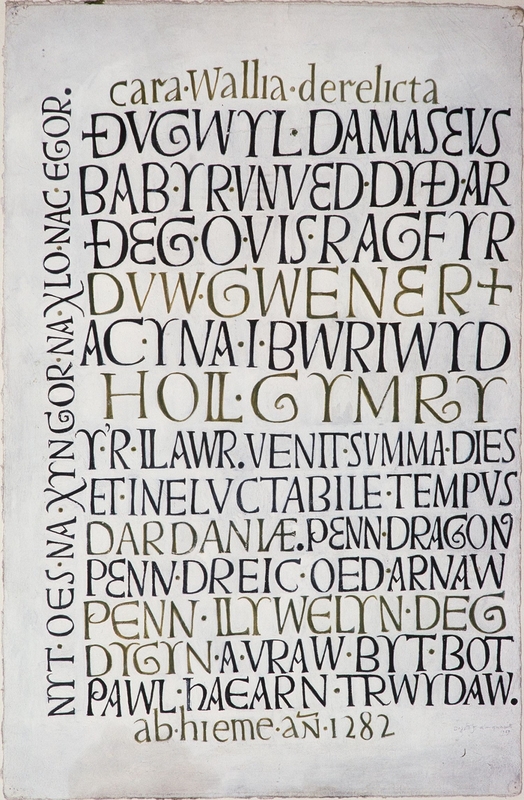

Portrait Bust of the Artist's Brother, the Sculptor John Gibson (1790–1866), RA

1837–1838

Benjamin Gibson (1811–1851)

The two men often travelled together and, while in London in 1844, John wrote to Benjamin in Rome asking him to pass a note on to Penry's servant. Around 1865 John wrote to friend Miss Yates, telling her the hot weather was making him and Penry think of moving, urged by Mary Lloyd writing in July that she did not want Penry to keep John lingering near Rome. The same month, sculptor William Theed hoped that John and Penry would come to England, while other letters reference the pair going on holiday together.

In later years, as John's health declined, it was Penry who took care of him. In 1864 the couple intended to visit Switzerland, but John's health failed at Leghorn and they stopped for him to regain his strength. Two years later, John suffered a stroke and, while paralysed in bed, Penry sketched him reading a get-well telegram from Queen Victoria.

John died on 7th January 1866. Hatti Hosmer wrote to Lady Eastlake: 'Very early on the morning of Mr Gibson's death Miss Lloyd and I were summoned hastily to his room – she remained with him till the last, but I left a kiss on his forehead and came away.' Hundreds attended his funeral at the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

In his will, John left his remaining works to the Royal Academy as well enough money to take care of them, however, as with many same-sex partners, he left the bulk of his estate to Penry. Also, Lady Eastlake asked Penry for detailed information about John when she came to write his biography.

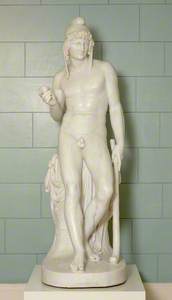

In recent years, blogger bklynbiblio, Alex Patterson, Roberto C. Ferrari and others have turned to studying John's work for its homoerotic content and the sexualisation of mainly nude male statues. Works such as Cupid Disguised as a Shepherd Boy and Narcissus (a story closely associated with homosexuality) have been examined for coded references to Greek same-sex passion, which would have been recognised by many classically educated viewers of the time. The unnamed blogger notes: 'By using coded visual language and imagery to channel (Ant)Eros in British art, Gibson helped pave the way for a conscious homosexual identity in the work of Simeon Solomon, Frederic Leighton, Hamo Thornycroft, Alfred Gilbert, and others.'

Despite homosexuality being illegal at the time, John and Penry, like many same-sex couples, defied convention and spent nearly 40 years together, both becoming successful artists in their own right.

Norena Shopland, writer and historian

John Gibson's sculptures can be seen in Wales at National Museum Cardiff, and Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru holds an archive of his papers. Penry Williams' work can be seen in the collections of Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Glynn Vivian and National Museum Cardiff.

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Further reading

Francis Power Cobbe & Blanche Atkinson, Life of Frances Power Cobbe as Told by Herself, S. Sonnenschein & Company, 1904

Lady Eastlake, Life of John Gibson, R.A., Sculptor, Oxford University, 1870

Norena Shopland, Forbidden Lives: LGBT stories from Wales, Seren Books, 2017

Harriet Hosmer & Cornelia Carr Harriet Hosmer letters and memories, Bodley Head, 1913

Alex Patterson, John Gibson – his life in Rome, National Museums Liverpool blog

Roberto C. Ferrari, Beyond Polychromy, 2013

Royal Academy of Arts Archive (references GI/1/128; GI/1/131; Gi/1/220; GI/1/224; GI/1/314; GI/1/331; GI/1/335; GI/1/369; G1/1/388)