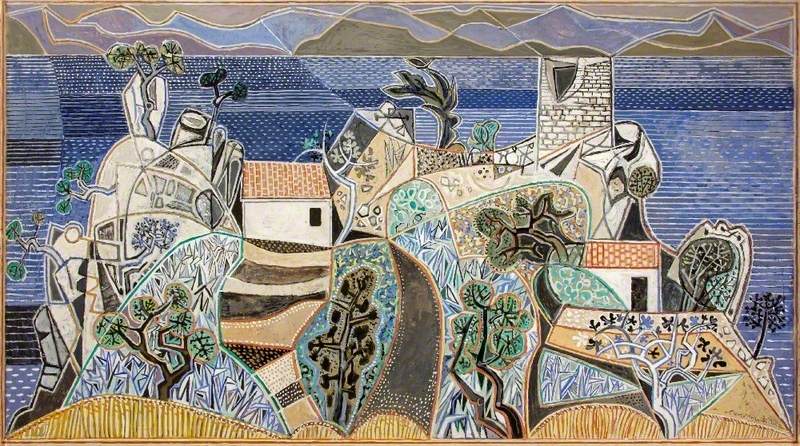

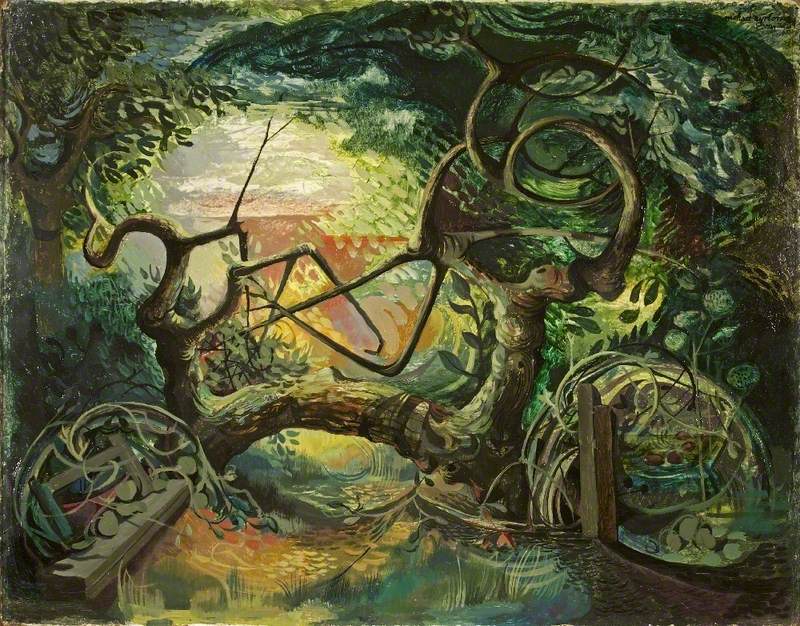

The painter John Craxton (1922–2009) was born in London and loved metropolitan life, but also responded deeply to landscape. He painted people and places and adored travel, particularly around the Mediterranean. Although some of his finest early landscapes were inspired by visits to Dorset and Wales, he found his spiritual home in Greece after the Second World War, settling in Crete in an old harbour-side house.

Living so much abroad, his presence was inevitably not much felt in the British art world – unlike the friend of his youth, Lucian Freud – though Craxton continued to visit London regularly and exhibit his work there. Since his death, however, there's been a notable move towards reassessing his achievement, and his paintings are commanding increasingly high prices.

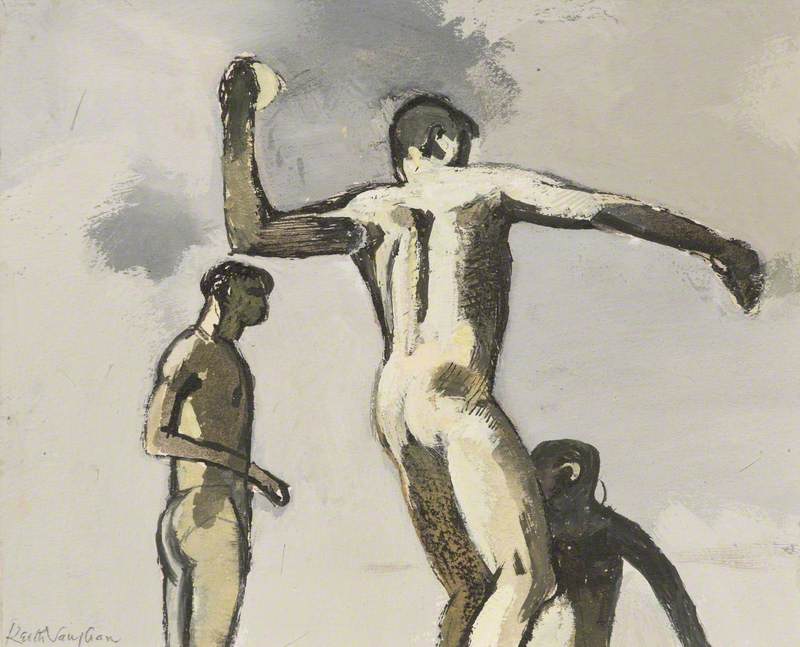

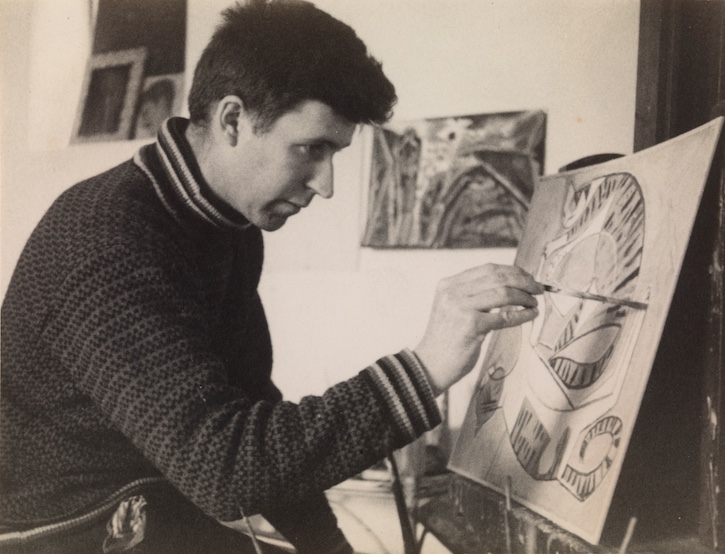

John Craxton painting 'Two Cats'

1956, photograph by Janet Craxton

I got to know Craxton in the 1990s and found him extremely good company when I visited his north London studio. His comments and perceptions about art of all periods were so precise and to the point that I felt they must be preserved for posterity. To this end, I conducted an extensive interview with him in 1998 and 1999 for the National Life Story Collection (a collection of recordings held at the British Library). I also wrote about Craxton and his work whenever I got the chance, which was thankfully quite often when I was working as art critic of The Spectator. But from the moment I got to know him, I wanted to write something more considered about him, preferably in the form of a book.

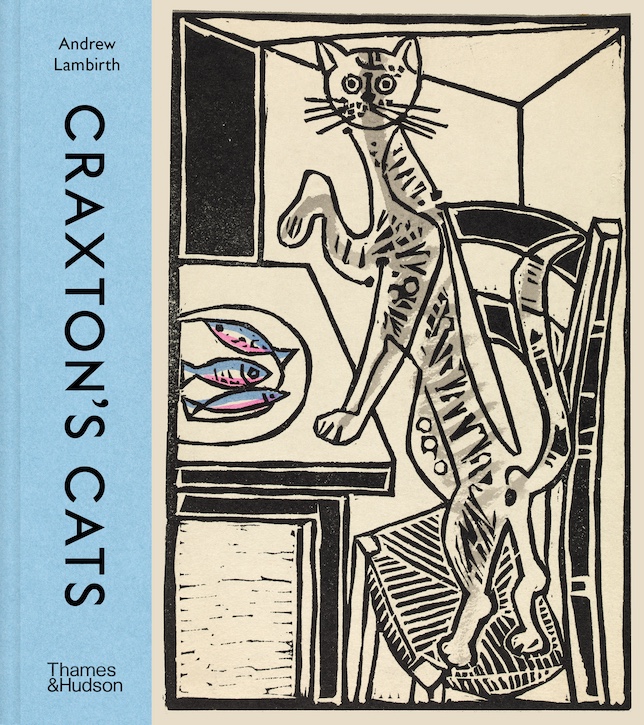

Craxton's Cats

Andrew Lambirth (2024)

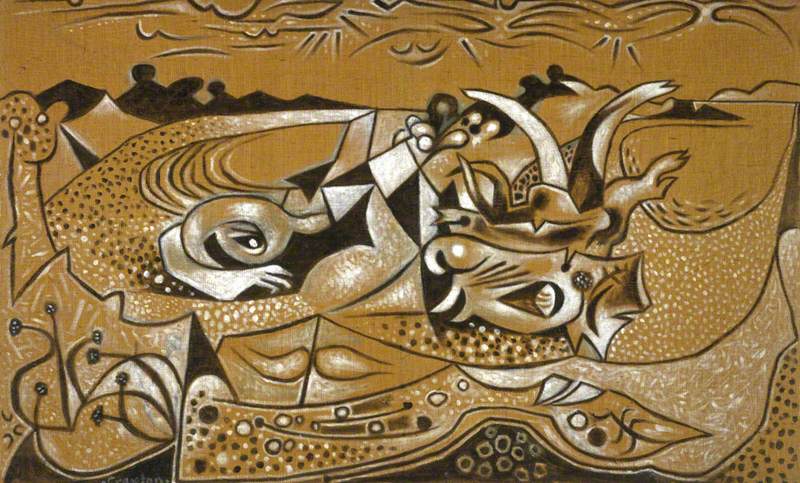

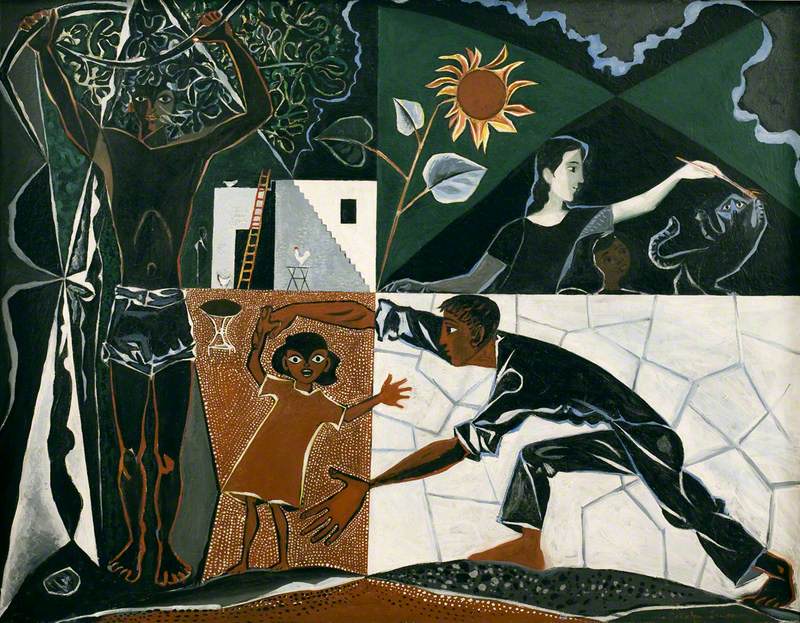

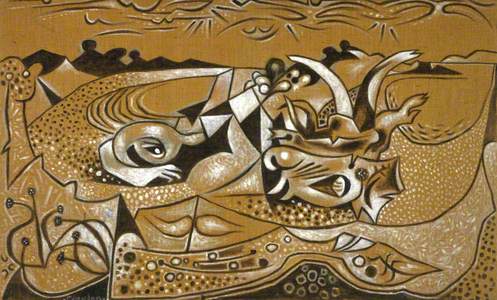

When I suggested that I put together a book called Craxton's Cats, he responded with enthusiasm. Cats had always been part of his life and he had drawn and painted them from an early age. Later he made prints about them, and often used these as Christmas cards. He loved cats, and understood them very well, as can be seen from the different situations he depicts them in. In Black Greek Landscape with Figures (1949–1950), he includes a cat in this four-part account of life on the land. A woman and child play with a cat in the top right-hand quadrant of the picture, underlining the important role cats have in daily life.

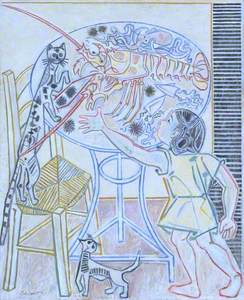

In Still-Life with Cat and Child (1959), Craxton focused intently on the daring ruthlessness of hungry moggies when in the presence of an unguarded table of delicious fish. This painting, now in the Tate, is a masterpiece of witty linearity, with the hugely elongated form of the main marauding cat reaching up to seize a fishy lunch (squid, lobster, octopus or sea urchin).

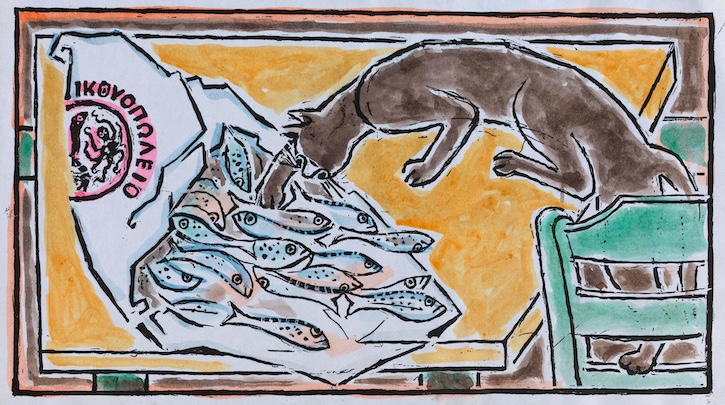

Craxton knew cats, and a lot of the semi-feral cats he drew in Greece stole food whenever they could. Besides the Tate's painting, there is another from the same period, simply called Cat, the feline again up on a chair to reach a fish-laden table.

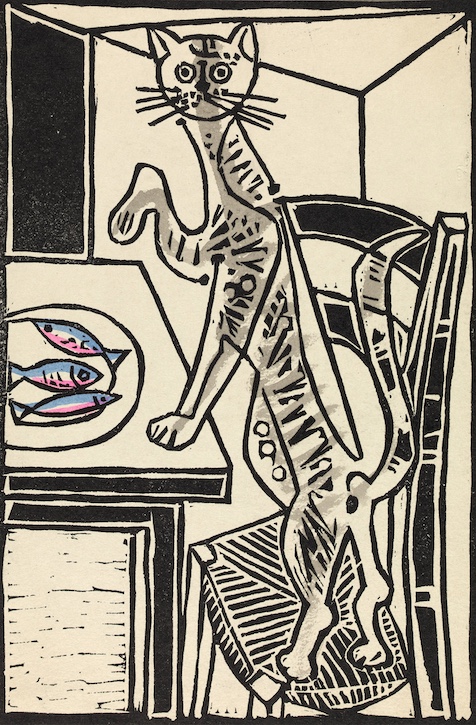

Cat

1958, hand-coloured linocut by John Craxton (1922–2009)

Note the same upraised foppish paw, and the caught-in-the-act expression of displeasure. A third, even more active version, is Cat Stealing Fish, from the 1990s.

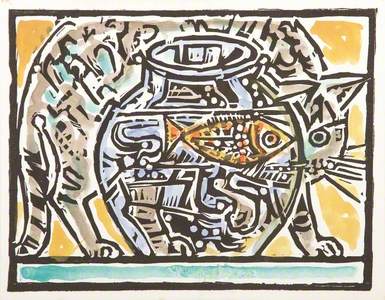

Cat Stealing Fish

1990s, hand-coloured digital print by John Craxton (1922–2009)

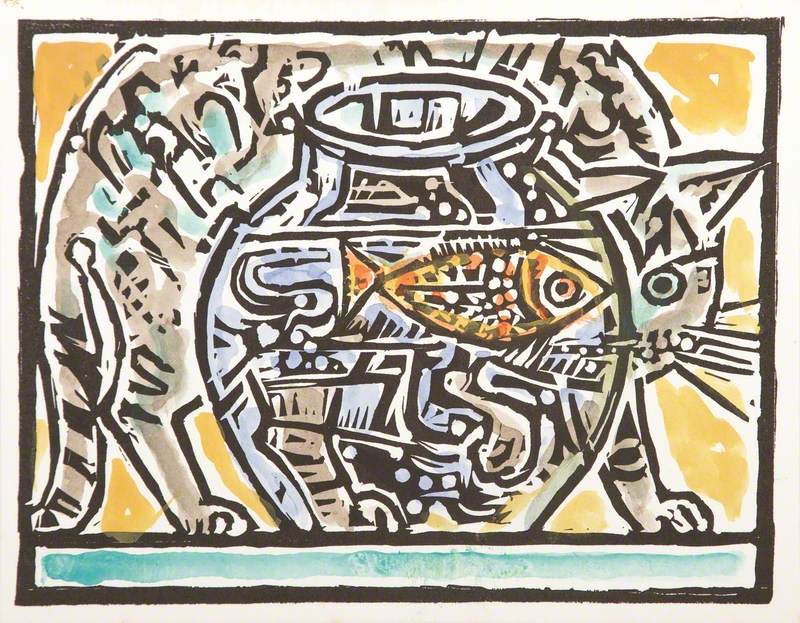

But cats do not always get their prey, as the beautifully executed hand-coloured linocut Cat and Goldfish (1975) makes clear. Here the fish is safe within its bowl, unless the cat manages to knock the whole thing over, risking an unwelcome drenching for itself. In this work, Craxton plays brilliantly with pattern and transparency, reality and illusion, in a tightly packed composition of virtuoso design. There are a number of variations on this image – the hand-colouring altering the emotional timbre of the piece with, for instance, increased use of red and yellow.

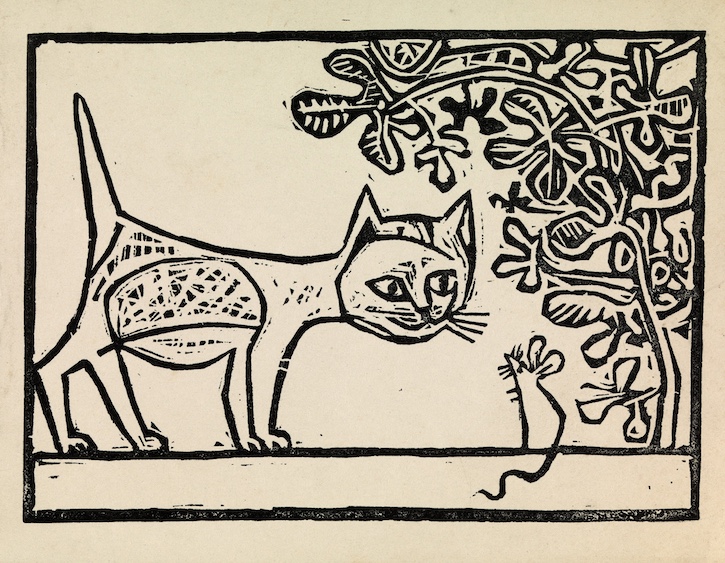

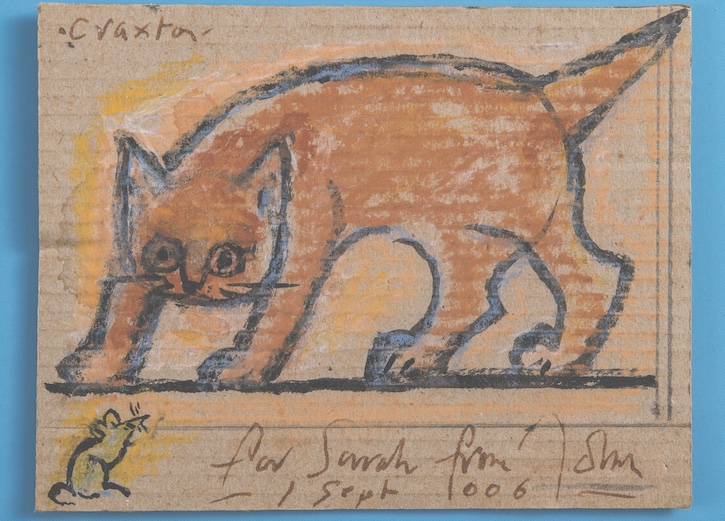

Cats have an acute sense of curiosity, when the mood takes them, and Craxton illuminates this through a number of pictures of youthful moggies investigating other animals and insects. The bold mouse and the timid kitten is a classic role reversal first seen in Cat and Mouse under a Fig Tree of 1957. The image recurs, most charmingly perhaps, in Kitten and Mouse of 2006.

Cat and Mouse under a Fig Tree

1957, linocut by John Craxton (1922–2009)

Kitten and Mouse

2006, mixed media on cardboard by John Craxton (1922–2009)

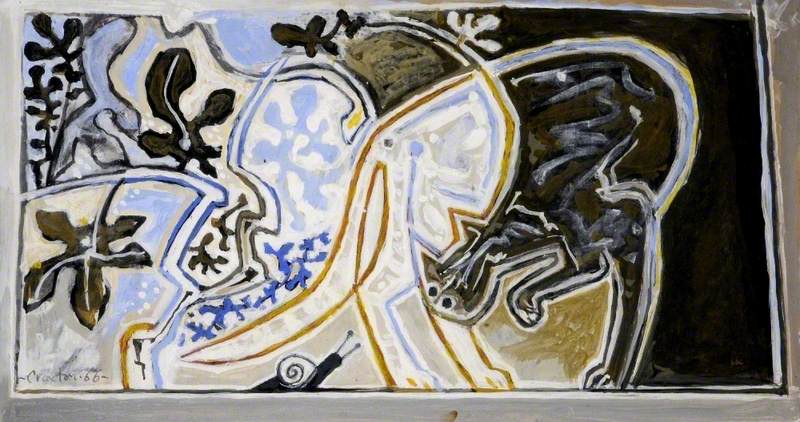

Then there is a sequence of cat and ant pictures, though the ant looks more like a termite, and quite capable of doing the cat some damage. Another pairing appears in Cat and Snail (1966), in Sheffield Museums. Once again, we see the decorative nature of Craxton's art – though the word 'decorative' is in no way a criticism for it is an essential ingredient in painting. Cat and Snail depicts a cat lyrically turning on itself to create a series of arabesques which alternate with dark and light on foliage. The branches of the fig tree become almost indistinguishable from the lines of the cat's body, as the sprung rhythm turns ingeniously from flatness into three-dimensional form.

Rather gratifyingly, people have said my little book offers an accessible introduction to Craxton's art. Well, it's certainly true that I knew Craxton quite well, and spent many entertaining hours in his company. We looked at art together and talked about artists past and present. He was also a great gossip, full of the most wonderful stories, about the varied people he had known – from the prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn to the famous statesman and amateur painter Winston Churchill.

Craxton was an immensely sociable person, who seemed to be interested in everyone he met, which of course brought out the best in them. He was such an asset at lunch and dinner parties that his work was constantly interrupted by invitations to social functions that he rarely turned down. He loved dance in all its forms, from ballet to Greek dancing in a tavern, and drew many dancers – including cats! – besides designing costumes and sets for Covent Garden.

Dancing Cats

1970s, oil on panel by John Craxton (1922–2009)

And herein lies a crucial aspect of his character that was to have a potentially deleterious effect on his art: he would rather enjoy life than work in the studio. Often he was able to do both in the course of a day or a week, but his active social life did interfere with consistent artistic effort. When it came to priorities, art was crucially important, but he felt it could always wait for another day. As Noel Coward put it, life was for living.

And in this, cats set a fine example, as can be seen in my new book. There are many moods captured here, from the playful (cat with a ball) to the watchful (cat at a mouse hole), as Craxton's moggies are depicted hunting, asleep, rolled into a ball, swiping at butterflies, begging for food or affection, having a stand-off with a cockerel, or innocently drinking milk.

Cockerel and Cat

1957, tempera on board by John Craxton (1922–2009)

Craxton was an artist who, although blessed with the lightest of touches, could turn from the celebration of life to a thoughtful meditation on death, as in the Warhol-like Cat and Skull of 2003.

Cat and Skull

2003, acrylic tempera on canvas by John Craxton (1922–2009)

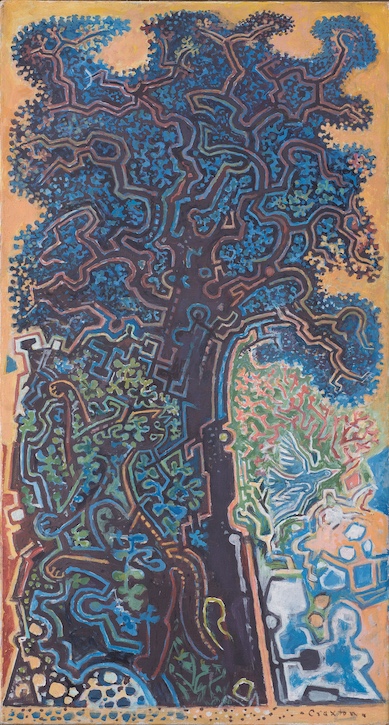

And if all this were not variety enough, take a look at the intricate puzzle pictures he also painted, such as Landscape with Cat and Bird (1987), in which the outline of the cat is almost lost in the abundant foliage.

Landscape with Cat and Bird

1987, tempera on canvas by John Craxton (1922–2009)

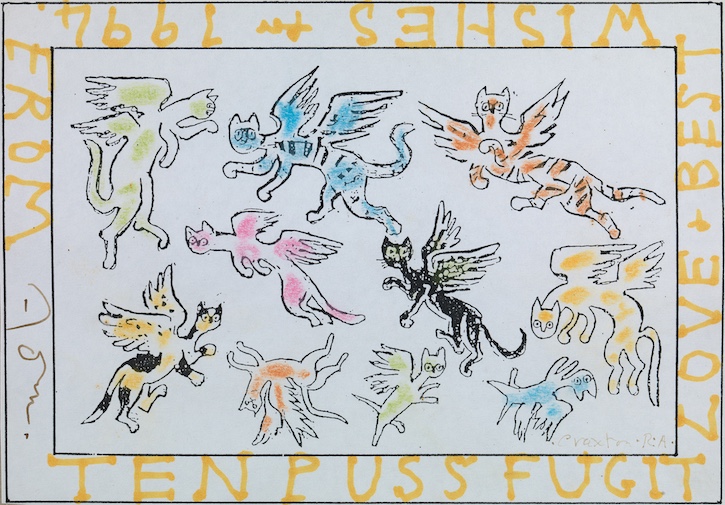

Cats gave Craxton ample opportunity to exercise his visual and verbal wit: perhaps the classic example being Ten Puss Fugit, of 1994, in which the Latin phrase for 'time flies' (tempus fugit) is given a characteristically feline interpretation.

Ten Puss Fugit

1994, hand-coloured digital print by John Craxton (1922–2009)

Undoubtedly, for John Craxton, cats were the measure of all things.

Andrew Lambirth, writer, critic, and curator

Andrew's most recent book, Craxton's Cats, is published by Thames & Hudson

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation