The National Gallery is exceptionally fortunate in possessing three painted portraits by Jan van Eyck. Famous throughout Europe from the fifteenth century onwards, the painter from the Low Countries achieved his success through the extraordinary way in which he manipulated the properties of oil paint to mimic the appearance of light falling on objects, illuminating interiors and creating a sense of atmosphere in scenes set outdoors.

So, I went to Ghent. Saw the restored Ghent Altarpiece by Van Eyck. Had a good look at the Holy Lamb everyone is giggling about. And... it’s absolutely marvellous. So much more intense and 3D. Gives the altar a powerful focus where previously it felt vague. Recommended! pic.twitter.com/fTI8OwxRUS

— WALDEMAR JANUSZCZAK (@JANUSZCZAK) January 26, 2020

He was, with his brother Hubert, the acclaimed painter of the so-called Ghent altarpiece, completed in 1432 for a family chapel in the cathedral of St Bavo at Ghent, a painting on the large scale. But he was also a notable portraitist, painting his subjects at a scale rather less than life but making their individual character vividly present.

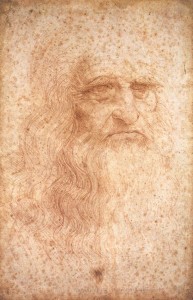

One of The National Gallery's paintings is usually thought to be a self-portrait, dated 1433.

Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?)

1433

Jan van Eyck (c.1380/1390–1441)

It remains in its original gilded wooden frame, inscribed as though carved into the frame: the illusion is extremely convincing. One text below the image says 'Van Eyck made me on 21 October 1433', and one above reads 'As Eyck can', a punning suggestion that this is what I/Eyck am capable of. This was Van Eyck's proud motto.

In 1433 Van Eyck was at the height of his powers and his career. He had joined the court of Philip, Duke of Burgundy a few years earlier in 1425 and was well paid for his services, carrying out tasks such as travelling to Portugal in 1428–1429 to take the portrait of Isabella of Portugal, Philip's future bride.

Settling in Bruges he was also able to take on commissions for rich patrons such as the Italian merchant Giovanni Arnolfini, for whom he painted in 1434 the famous double portrait which is also in The National Gallery.

Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife

1434

Jan van Eyck (c.1380/1390–1441)

Here again Van Eyck proclaimed his authorship, inscribing the words in Latin 'Jan van Eyck was here' on a wall in the centre of the composition, just below a mirror with a reflection in which we may just be able to discern the artist entering the room to be greeted by Arnolfini.

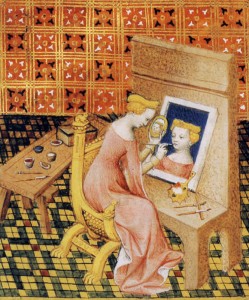

The National Gallery's third van Eyck portrait has perhaps always tended to be overshadowed by these other two: the smallest of the three, it lacks its original frame, and its subject is set simply against a dark background.

Portrait of a Man ('Léal Souvenir')

1432

Jan van Eyck (c.1380/1390–1441)

Wearing a green hood which extends over his shoulder, and a red robe lined with fur, he holds a paper or parchment roll in his right hand, and gazes out to our left, as if oblivious to our presence. In contrast, the men in the other two portraits meet our stare directly. But there is more to the portrait. Its most intriguing feature is the stone parapet set in front of the figure. This is inscribed as though carved with the letters 'Leal Souvenir' – 'loyal memory'.

Above it in white is a Latin inscription giving the precise date: 'done on 10 October 1432 by Jan van Eyck'.

Below is a much smaller inscription also in white, using what appears to be a mixture of Greek and Latin letters. Some have read this as 'Tymotheos', creating a name for the subject of the portrait, but more recently it has been deciphered by Lorne Campbell as two words meaning 'then God': 'Otheos' was a name for God.

This interpretation leaves the question of the identification of the sitter as mysterious, and, as the format of the portrait resembles a type of tombstone, it's been suggested that it was painted as a memorial to a sitter no longer alive.

Have you visited our Van Eyck exhibition online yet? The largest show in history, closed too early but now entirely online via https://t.co/xwZ2eoMZES. With multilingual video and audioguide for adults and kids, and free for all.#vaneyck #flemishmasters #onlineexhibition pic.twitter.com/IKxBTlo4Pv

— MSK Gent (@mskgent) July 9, 2020

The decision to lend the portrait to the major Jan van Eyck exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent (which sadly closed early due to the COVID-19 pandemic), where many of his paintings are juxtaposed with recently cleaned and conserved portions of the great Ghent altarpiece, led to the decision to clean and restore the portrait, which had long been covered in a thick yellow varnish.

If it was to be displayed with the newly revealed portraits of the donors of the Ghent altarpiece, Joos Vijd and his wife Elizabeth Borluut, its date 1432 chiming with that of the altarpiece itself, then showing it in the best possible condition would enormously facilitate making the comparisons that would enable a deeper understanding of Van Eyck's work. Additionally, it gives the public a better experience of the painting, which has continued on its return to the Gallery's permanent display.

Portrait of a Man ('Léal Souvenir'), before and after restoration

1432, oil on oak by Jan van Eyck (c.1380/1390–1441)

Under the varnish Van Eyck's painting was found to be in a very good condition, some of his original paint covered up by old areas of restoration which could easily be removed. The gains were striking: the sitter now appears fully three dimensional once more. His blue eyes gleam, his fair hair is made visible again and, most strikingly, his hand which holds the document comes forward into space. The chips deliberately painted into the stone parapet are crisply apparent, contrasting with the soft fur of the robe and the flesh of the sitter.

If this still unidentified man – a Northerner or a fair Italian? – was indeed painted after his death then today he appears more alive than ever.

Susan Foister, Deputy Director, Director of Public Programmes and Partnerships and Curator of Early Netherlandish, German and British Painting at The National Gallery, London