In Out of the Cage: The Art of Isabel Rawsthorne, the biography written by art historian and curator Carol Jacobi, she describes Isabel Rawsthorne (1912–1992) as being 'hidden in plain sight'. Born Isabel Nicholas, the British artist and set designer was a prominent figure in the leading bohemian cultural circles situated in London and Paris.

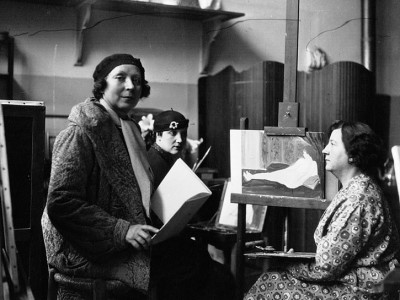

Isabel Rawsthorne

1933, photograph by John Everard

As Jacobi asks, '[she] was showing revolutionary work at leading avant-garde galleries of day. How did she disappear from the history of art?'

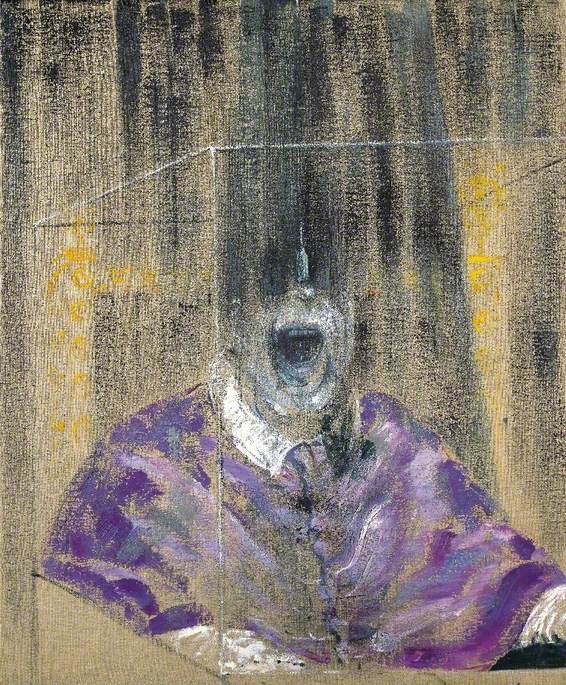

Her unconventional friendships and relationships with the major (male) names of the century, notably Jacob Epstein, André Derain, Balthus, Alberto Giacometti, Pablo Picasso, and Francis Bacon, meant that she was predominantly remembered as muse and model rather than an artist in her own right.

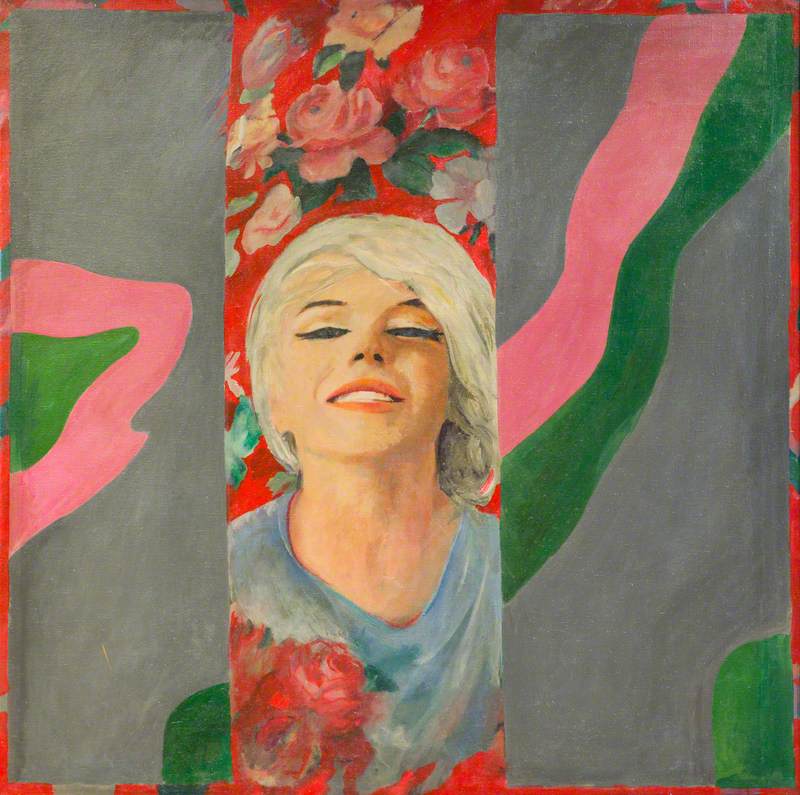

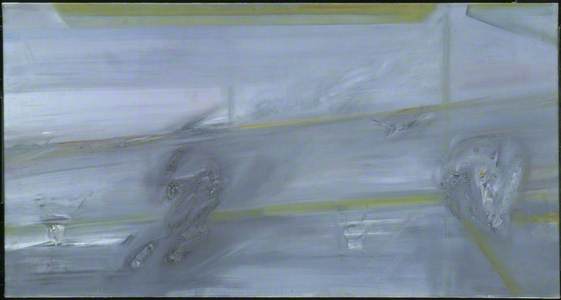

Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho

1967, oil on canvas by Frances Bacon (1909–1992)

She also married three times, and her artworks were therefore attributed to all of these surnames (Delmer, Lambert, and Rawsthorne). Led by an inquisitive attitude, her life was itinerant and independent. '[She] invented her life as she went along, through poverty, wars and social struggle, seeking the freedom to paint,' writes Jacobi. 'Her pictures, dominated by the body, were made in the spirit of research. Her unorthodox lifestyle was an extension of this research, an experiment in existence.'

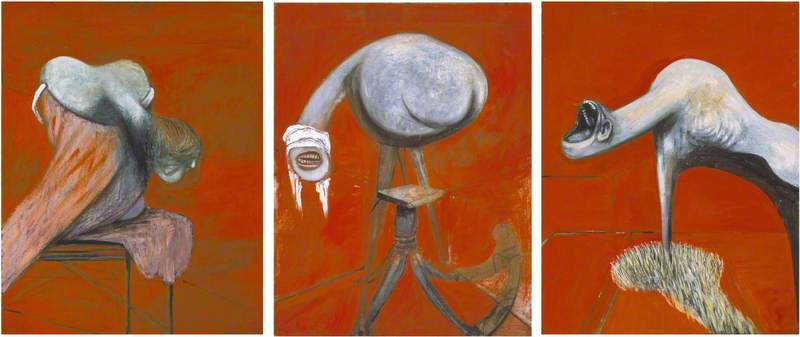

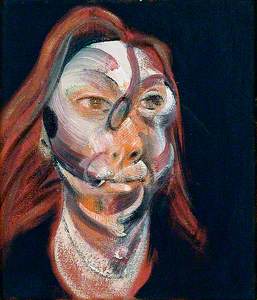

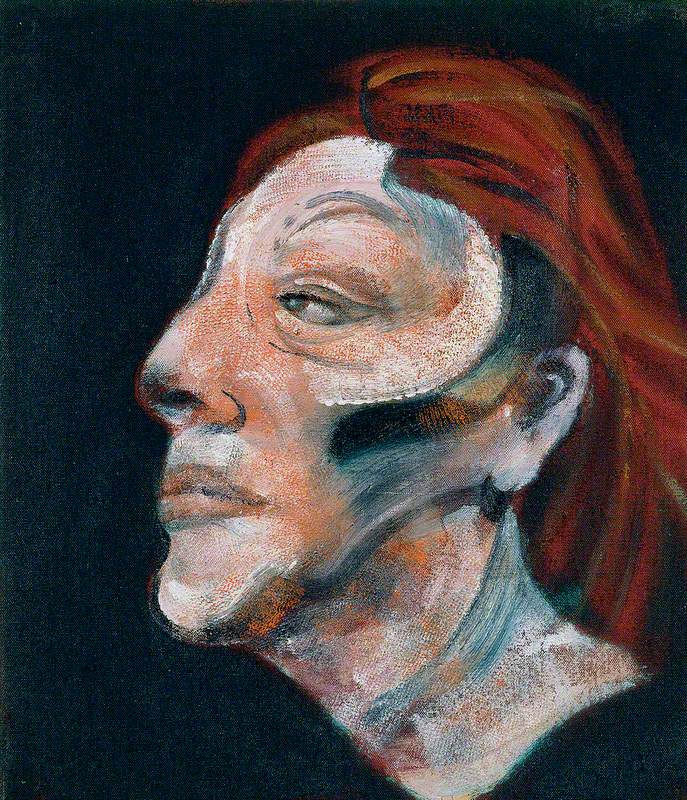

Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne

(panel 1 of 3) 1965

Francis Bacon (1909–1992)

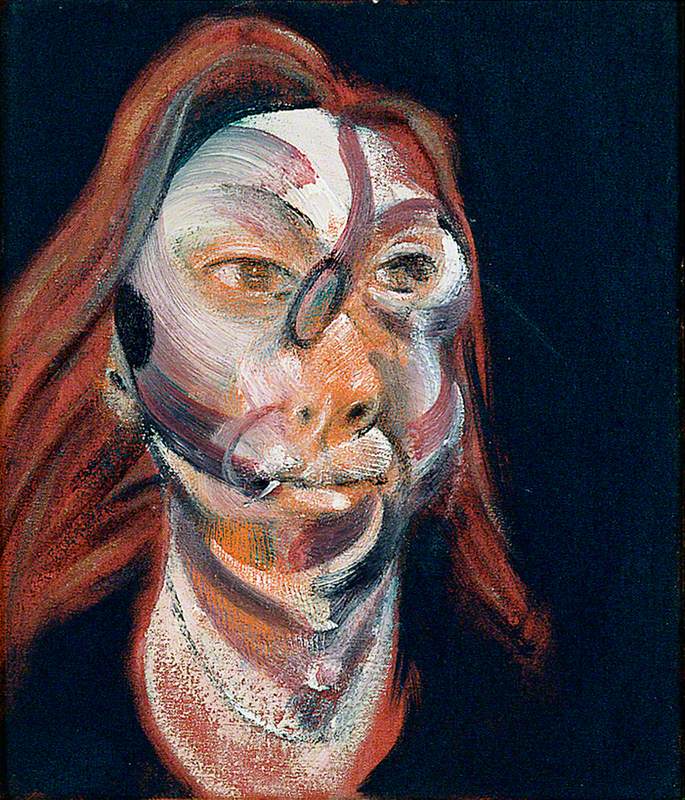

Three Studies for a Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne

(panel 2 of 3) 1965

Francis Bacon (1909–1992)

Rawsthorne was born in East London in 1912, the daughter of a mariner, and was later raised in Liverpool. Entering the Liverpool School of Art aged 16, she embraced the flourishing subculture she found there, setting up an alternative studio in Wood Street with her peers, naming themselves 'the thinkers', in which they defied the gender segregation of life drawing classes by posing naked for one another. This social arrangement and their rejection of the artist/muse binary – and also by extension, the divisions between men and women – was influenced by the progressive new thinking that was emerging among liberal society, especially in relation to marriage and sexual liberation. The spirited reassessment of gender roles and the refusal to conform to convention can be traced throughout Rawsthorne's life.

In 1931, Rawsthorne was awarded a scholarship to study at London's prestigious Royal Academy of Art. Enrolling on the painting course, she was disappointed to find the environment very conservative and stuffy, with most of her fellow students being wealthy dilettantes. She befriended Mervyn Peake, Peter Scott, and Frances Bruce, united by their frustrations with the repressive nature of the institution. By 1932, they had all left the academy. Without the security of her scholarship, Rawsthorne was in desperate need of income and shelter, and was introduced to the artist sculptor Jacob Epstein.

She began working as an artist's model at his home in Hyde Park but soon was invited to move in, living alongside his family, and becoming his studio assistant. The set-up afforded her the space and security to work on her own practice, and she produced hundreds of paintings and drawings over the next 18 months. Rawsthorne became Epstein's lover, travelling with him to Paris, and mingling with his artistic and literary set in London.

In May 1933, his bronze bust of her, Isabel, was shown at Leicester Galleries, sparking great public interest in the identity of the model. Later that year, at Valenza Gallery, Rawsthorne had her own sell-out exhibition. In 1934, she fell pregnant with Epstein's child. Margaret, Epstein's wife, was registered as his mother, and Rawsthorne moved to Paris soon after the birth.

In Paris, now living with the journalist Sefton Delmer, Rawsthorne rented a studio where she worked every day, in addition to regularly life drawing at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Montparnasse (where, unlike at the Royal Academy, she was granted the same access to nude models as her male peers), or sketching at the zoo in Vincennes. Every afternoon, artists gathered at Le Dôme Café.

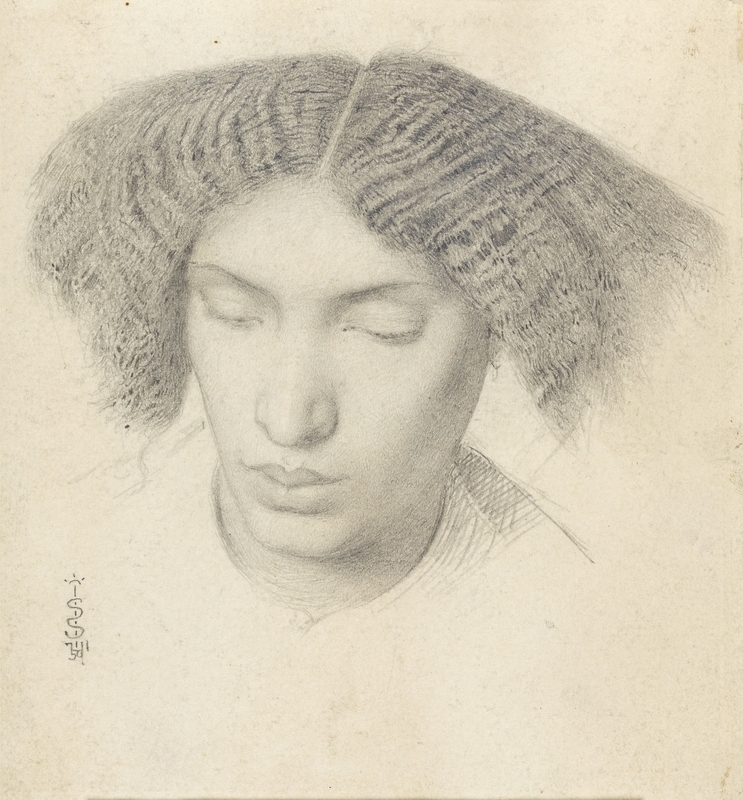

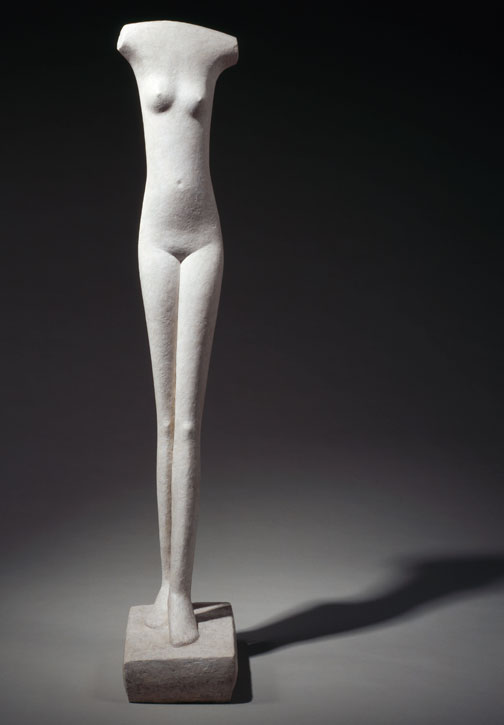

Through this milieu, in 1935, Rawsthorne began sitting for André Derain, and was introduced to members of the French avant-garde, including the artists Balthus and Picasso, the writer Georges Bataille, the Surrealist poets Paul Éluard and Tristan Tzara, and the sculptor Alberto Giacometti. Like she had with Epstein, and in line with her experiences at Wood Street in Liverpool, Rawsthorne posed for these artists as a friend and colleague, rather than as a professional model. Her modelling for Giacometti is demonstrated by Head of Isabel (1936) and Femme qui marche II (1935–1936), which is based on her elongated, svelte figure.

Femme qui marche II

1936, sculpture by Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966)

Rawsthorne and Giacometti's relationship, which became romantic, was mutually influential, with modern art at the centre, developing each other's working practice, and fuelled by the discussion of new ideas and creative visions. They were eventually separated by the Second World War, reuniting fleetingly in 1945, but remained in contact for the rest of their lives. Rawsthorne moved to England with Delmer, who worked as a British propagandist. She too reportedly worked for the Political Warfare Executive, creating artwork for their black propaganda leaflets and publications.

Three Fish

1948, oil on canvas by Isabel Rawsthorne (1912–1992)

Rawsthorne returned to Paris in 1945, where her circle expanded to include writers and philosophers, including Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Her work during this time was influenced by existential phenomenology, painting minimal still lives of inanimate objects or dead animals: cut flowers, a felled bird, shells, feathers, leaves.

In 1947, divorced from Delmer, she moved back to London, working intensively. She married Constant Lambert, the British composer, conductor, and Founder Music Director of The Royal Ballet. Lambert, too, was familiar with being an artist's model, having been painted by the artist Christopher Wood on numerous occasions during the 1920s. Wood had also created designs for Lambert's 1925 production of Romeo and Juliet, though they were never used.

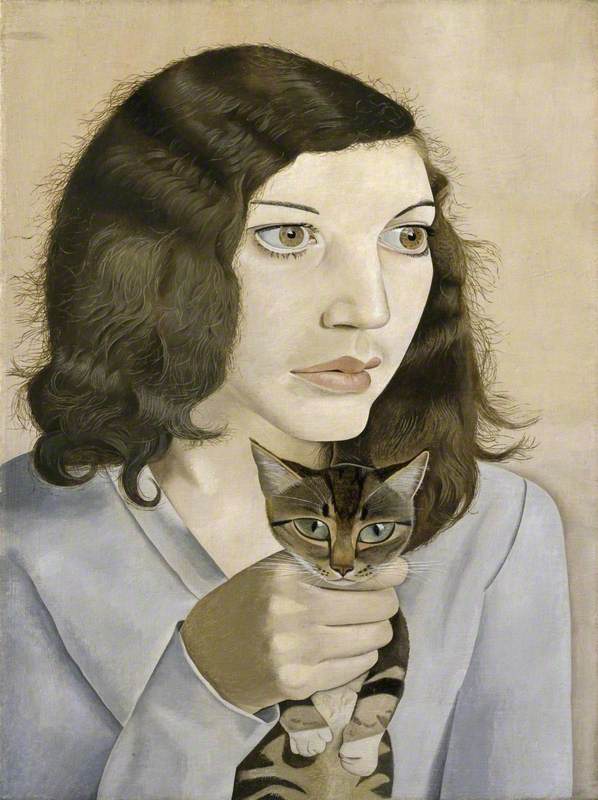

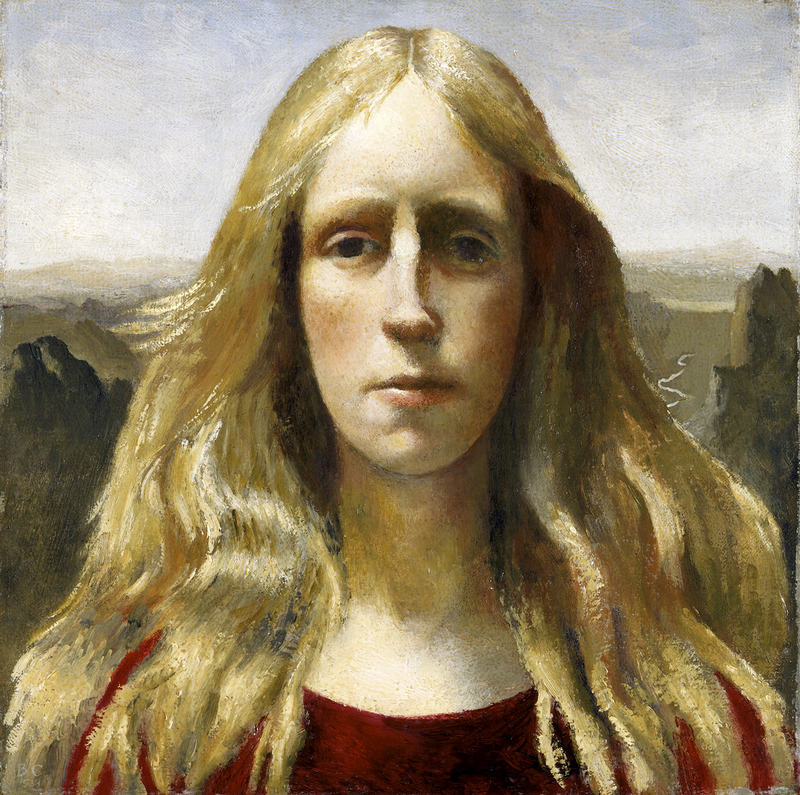

Rawsthorne and Lambert lived together near Regent's Park, where Isabel created a studio space in their apartment on Albany Street. Their relationship has been described as being mutually creative and professionally transformative. In 1949, Rawsthorne's solo exhibition at the Hanover Gallery garnered great national and international attention, seen as representing the new 'School of London'. The influential art critic and curator David Sylvester selected her as one of five 'London painters of outstanding talent who would challenge Paris and New York', alongside Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Peter Lanyon, and John Craxton.

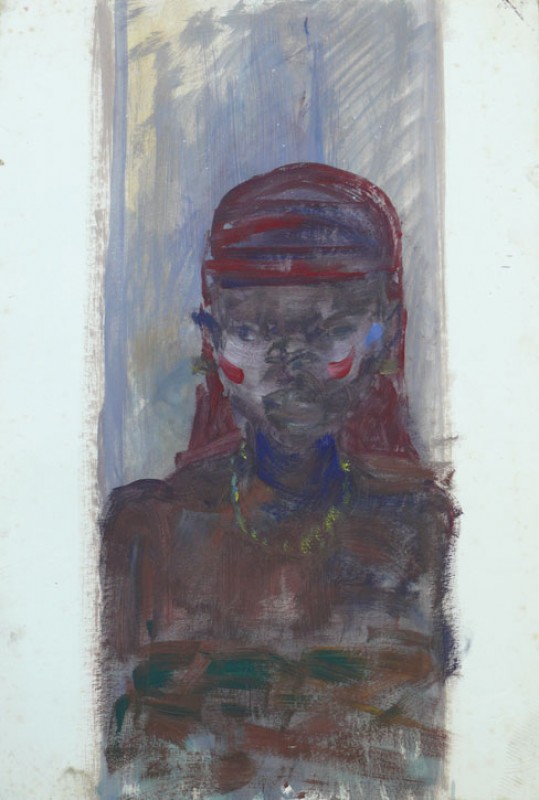

In 1950, Constant Lambert was commissioned by Sadler's Wells to write the music for a dance for the Festival of Britain. He composed an orchestral piece about the Greek mythological figure Tiresias, who experiences life as a man and a woman. Rawsthorne was invited to be the set designer, experimenting with intense and clashing colours. Dance was at the centre of the avant-garde, synthesizing radical developments in music, art, and choreography.

The production was derided in the mainstream British press but celebrated in Paris and New York, celebrated for its philosophical and psychological themes. The ballet daringly explored identity, eroticism, and the fluidity between masculinity and femininity. These were issues personal to Rawsthorne's circle, where non-monogamy was the norm, with gender categories and sexual identity between partners often permeable. Lambert died in 1951, and Rawsthorne married their mutual friend, the composer Alan Rawsthorne.

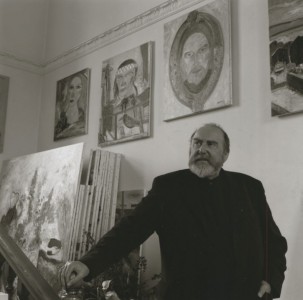

The art historian and writer Michael Peppiatt has suggested that Francis Bacon and Rawsthorne shared an 'animal exuberance'. After an initial meeting in Paris in 1946, in the late 1940s they visited one another's studios in London. In the years that followed, they became close friends, moving in the same milieu of artists and writers that frequented various Soho haunts, notably the French House and Muriel Belcher's Colony Room. Along with Henrietta Moraes, Rawsthorne became one of his favourite female models, similarly working from original photographs taken by John Deakin.

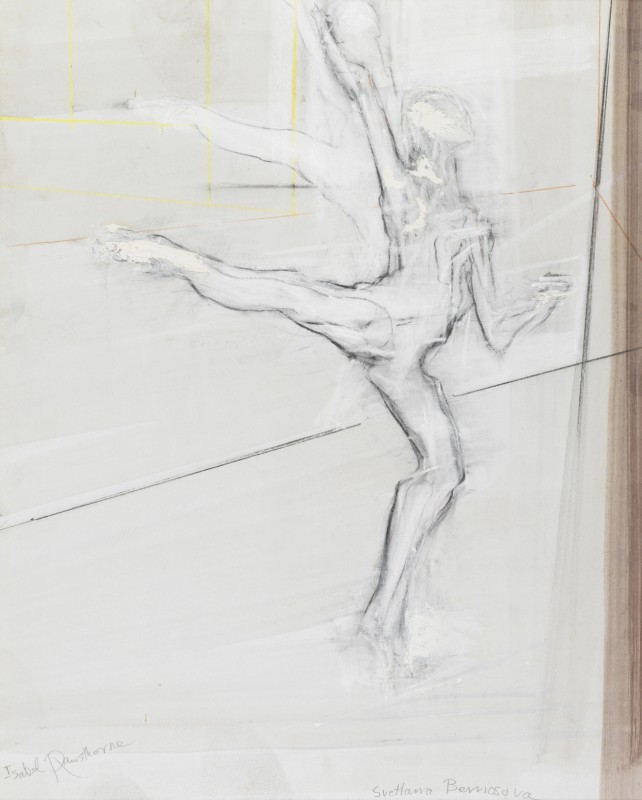

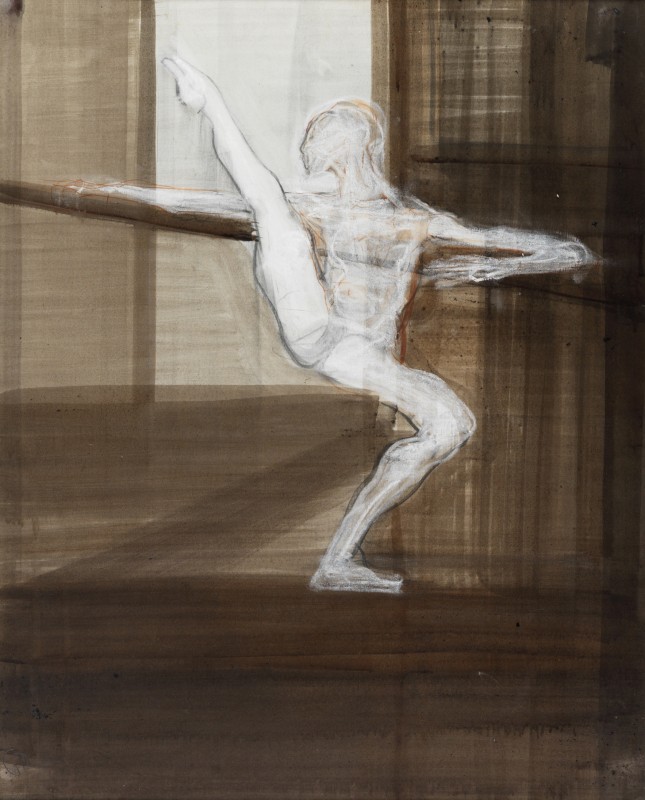

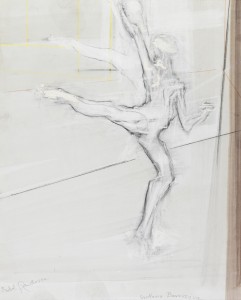

Between 1952 and 1955, Rawsthorne designed the sets and costumes for multiple ballet and opera productions at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, establishing a reputation as a respected designer. Her contacts at Sadler's Wells meant she had access to the dancer's rehearsal rooms, and often went there to sketch, interested in studying bodies in motion, a development on the life drawing practice she had honed throughout her artistic career. Rawsthorne drew and painted the ballerinas Margot Fonteyn, Antoinette Sibley, Michael Somes, and Rudolph Nureyev. The mirrored rooms added a new dimension.

Margot Fonteyn

1968, drawing on paper by Isabel Rawsthorne (1912–1992)

Her understanding of the moving body was animated with her experiments with the moving line, articulating the agile body's curves, shapes, and gestures. The work's austere and spectral tone was influenced by her intrigue in transience and the fleeting nature of presence. In 1968, a series of oil paintings were exhibited at London's Marlborough Gallery. It was a huge success, and the show was attended by an elite group of cultural figures. They were shown again at October Gallery in 1986, to great acclaim.

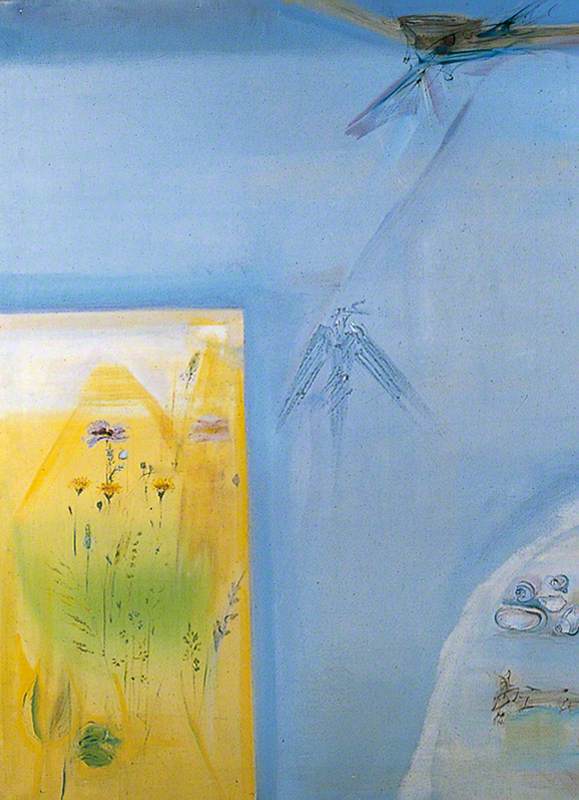

After the Marlborough show, Rawsthorne set aside her interest in figures and portraits and returned to wildlife, as depicted by her 'Migration' series. These paintings combined studies of local hedgerows, mistle thrushes, and birds in the wild, dominated by blues, yellows, and greys, inspired the local surroundings from her cottage in Little Sampford, Essex.

After Alan Rawsthorne died in 1971, the artist travelled alone and with friends, spending time in Australia, Greece, Rome, and Naples, and sketching the birds, animals, land, and sea, she encountered there. She continued to work into her old age, despite suffering from glaucoma.

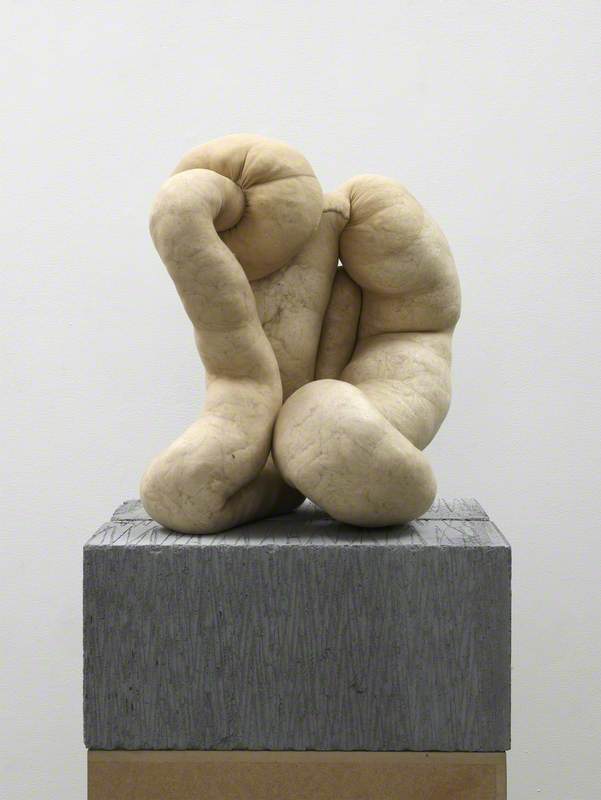

The sculpture of Rawsthorne by her friend, the artist and carver Roy Noakes, made in 1985, is the last portrait of her, and the only one she commissioned. She died in 1992. Noakes' widow, Biddy, has been engaged in the preservation of Rawsthorne's legacy, placing works in national collections, and was involved with the donation of two hundred drawings and paintings to The New Art Gallery Walsall in 2012.

Philomena Epps, writer

You can find out more about Isabel Rawsthorne in a video made by Art UK partner HENI Talks: