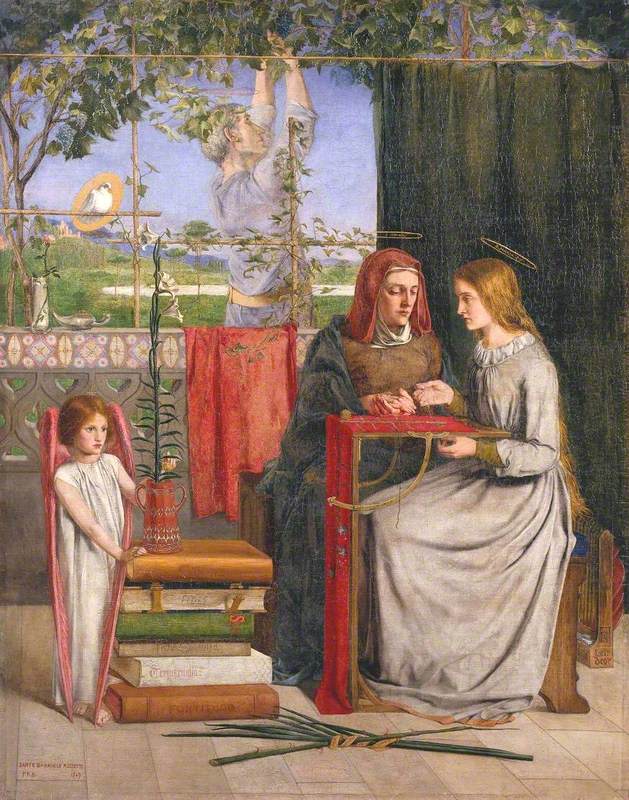

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1848–1849) shows Mary's mother, Saint Anne, teaching her daughter embroidery. The picture is full of symbols, including those which will reappear in scenes of the Annunciation, when Mary is told she will conceive the Son of God.

The props are waiting to be deployed: the lily (symbol of Mary's purity), the embroidery frame shaped like the lectern at which Mary's reading will be disturbed by Gabriel, and Gabriel himself, waiting in the wings, ready to take over from the junior angel holding the lily pot. The Holy Spirit, in the form of a dove, waits patiently on its perch.

Along with the Nativity and the Crucifixion, the Annunciation is one of the great set pieces of religious art. It is celebrated by the Church on 25th March as the Feast of the Annunciation.

The Annunciation

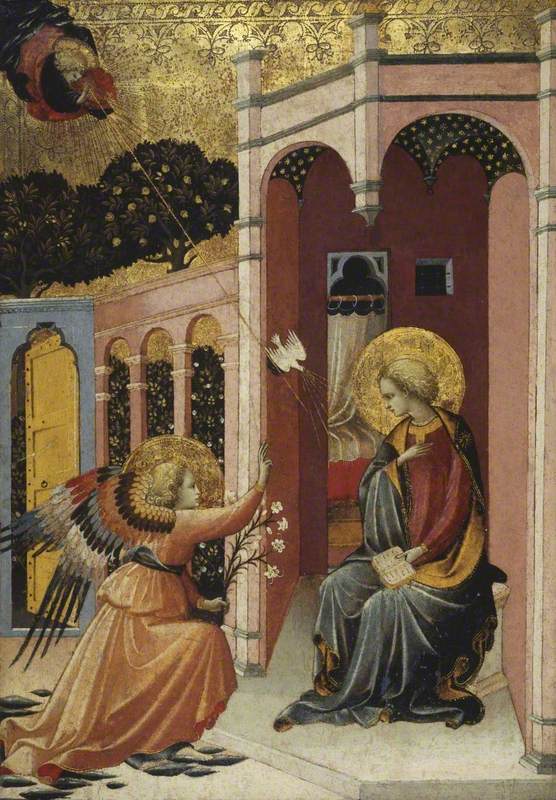

(diptych) c.1450–1455

Francesco di Stefano Pesellino (c.1422–1457)

As described in Luke 1:26–38: in the sixth month, the angel Gabriel was sent from God to a town in Galilee called Nazareth, with a message for a girl betrothed to a man named Joseph, a descendant of King David; the girl's name was Mary. The angel went in and said to her, 'Greetings, most favoured one! The Lord is with you'. But she was deeply troubled by what he said and wondered what this greeting might mean.

Medieval and Renaissance depictions show Gabriel visiting Mary in a covered place, a room or open loggia, which can appear as a gazebo-like structure.

The architecture around Mary presented a challenge to artists who were grappling with representing three-dimensional space. In Duccio's fourteenth-century depiction, a rudimentary sense of depth is achieved, with the central column delineating Mary's space from that of Gabriel's. As Gabriel passes through the arch and behind the red pillar, there's a real sense of movement towards the startled Mary.

Duccio's Annunciation influenced other fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Italian artists, such as The Master of the Judgement of Paris. The loggia in which Mary sits provides an enclosed space symbolic of Mary's inviolate chastity, but one which is open to the entrance of Gabriel.

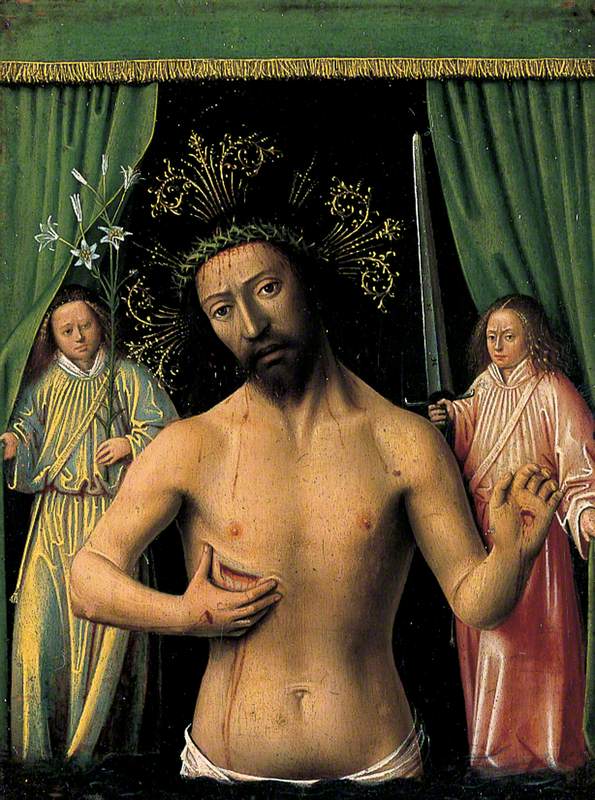

For artists to capture the drama of this private moment – of Gabriel appearing before Mary to deliver the news that she, a virgin, is pregnant with the Son of God – depends heavily on gesture. Gabriel extends an arm and a hand as if in blessing, often with a magician's panache.

In Sandro Botticelli's Annunciation (c.1490–1495), Gabriel rushes towards Mary to break the news.

Mary may flinch or turn away, her hand raised in modesty and disbelief. These tropes recur, with variations, as does the Holy Spirit shooting its bolts of golden light from above, symbolic of the miraculous conception. In this crossfire, no wonder the unsuspecting Mary recoils.

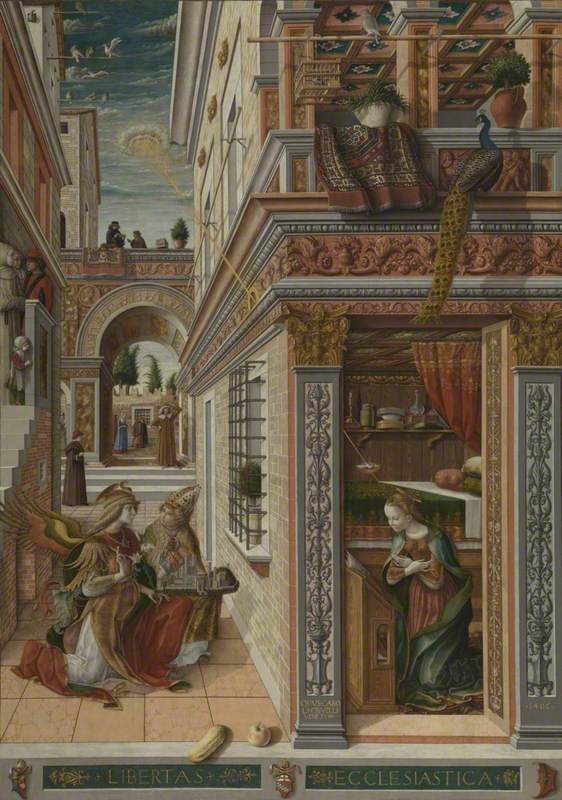

While many Annunciations present the simple shared intimacy of Mary and Gabriel, others introduce other characters and a more elaborate setting. Carlo Crivelli's Annunciation (1486) demonstrates a vigorous application of single-point perspective which draws the eye back between buildings in what is evidently a wealthy city (although the trajectory of the Holy Spirit's shaft of light follows an impossible course in penetrating Mary's chamber).

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius

1486

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Crivelli's Annunciation exemplifies the Renaissance interest in Humanism, which artists expressed by presenting religious figures as distinctly and recognisably human. Religion had become 'an affair of the individual and his own personal feeling', as historian Jacob Burckhardt described it, and this is well represented by the exchange taking place in the street outside Mary's chamber.

Remarkably, Gabriel has been interrupted by the local Saint Emidius, on his way to meet Mary. Emidius holds a model of the town of Ascoli Piceno, marking the day – 25th March, the Day of the Annunciation – when his town was granted self-government.

Mary is in an ornately decorated building surrounded by expensive objects, a far cry from the spartan simplicity of other Annunciations, and at odds with the poverty she supposedly endured. While this depiction reflects the material riches (including Persian rugs from overseas) that international trading brought to this town near the Adriatic coast, its elaborate detail, heavy with symbolism, is true to Crivelli's signature style.

In the second part of the account in Luke's Gospel, Gabriel tells Mary not to be afraid and Mary accepts her fate with the words 'Here am I. I am the Lord's servant; as you have spoken, so be it.' Many depictions show Mary acquiescing demurely and with quiet humility, as in Filippo Lippi's depiction (c.1450–1453).

By contrast, Nicolas Poussin's neoclassical Annunciation from 1657 has an eroticism approaching Bernini's famous sculpture Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1645–1652). Mary, eyes closed, arms wide, yields willingly to the smiling angel's message.

The art historian Heinrich Wölfflin contrasted the 'linear' nature of Renaissance art with the period which followed: the Baroque. For Wölfflin, Baroque art (roughly of the period 1600–1760), was concerned less with line and plane, and more with the expressive use of paint, and dramatic light and shadow.

In Philippe de Champaigne's Annunciation (c.1648/c.1456), the delicate golden Renaissance rays have been supplanted by an explosion of cloud-splitting light.

Tellingly, Mary and Gabriel are illuminated in what seems otherwise to be a place of darkness. A flock of winged putti surround the Holy Spirit, a common feature of Baroque religious art. The later Baroque was a time of sentimental attitudes to children in art and literature, which encouraged the presence of putti.

The rhetoric of Baroque religious painting, according to art historian Vernon Hyde Minor, 'exhorts, urges and appeals to the spectator to have confidence in and to feel protected by the Church'. In Bartolomé Esteban Murillo's Annunciation (c.1665–c.1670) the celestial realm imposes itself on Mary's earthly life, as symbolised by her sewing kit, both as an exhortation to Mary and to the devout viewer.

In Baroque interpretations, the architectural settings of Renaissance Annunciations are often replaced by intangible spaces engulfed in deep shadow and cloud. Everything is subordinate to the drama of the scene.

The mission of the Pre-Raphaelites was to make art with the formal and spiritual simplicity of the early Renaissance, and Rossetti's Annunciation, titled Ecce Ancilla Domini! (1849–1850), achieves this through its limited palette and clearly delineated forms. It is a work which straddles the old and the new.

Elements of traditional iconography are employed (the lilies and the dove) and, in its quiet reserve, it captures the mood of early Annunciations. At the same time, it gives a strong sense of two quite ordinary people in a room, with Mary rising from a divan (a clear departure from tradition) and Gabriel wingless (but floating, with flames at his feet).

Rosetti's Annunciation was not well received. One critic called it 'a perversion of talent' and attacked it for ignoring principles of colour and composition. To our eyes, the sexual nature of the image is undeniable. Gabriel's nakedness is glimpsed through the slit in his robe, and he wields the lily, which is pointed at Mary's belly, who appears cornered in the claustrophobic space of her bedroom.

The scarlet embroidery frame recalls Rossetti's own The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, painted a couple of years earlier.

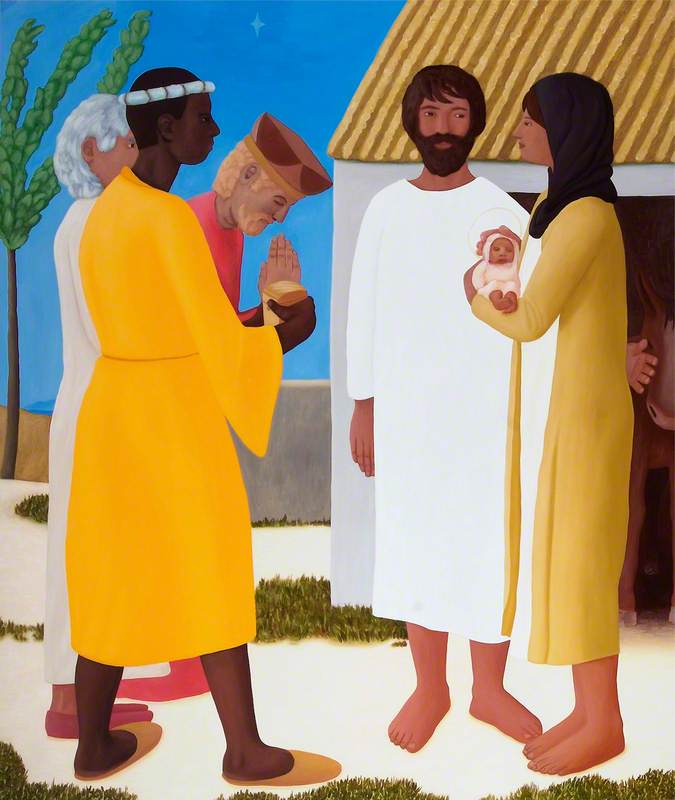

Two contrasting tendencies of modern Annunciations show Gabriel and Mary in close proximity, touching or walking side-by-side, or as single figures – often Mary alone, but sometimes Gabriel too. Reflecting our less formal, secular age, these works eschew the old iconography and its supernatural elements, while retaining the intimacy of the moment and the imposition on Mary.

Helen Elwes's contemporary Annunciation is a return to the simplicity of Medieval depictions.

Its quiet humility brings to mind the works of Fra Angelico and Duccio. The reassuring hand on Mary's shoulder is sincere and demystifying. The architecture of early Annunciations is alluded to by the bay window and the curtain, and the light is the plain daylight that is also, for the believer, the glory of God.

Artists through the ages have portrayed the Annunciation in varied and wondrous ways. Though momentous for the devout, these scenes have a fundamental human poignancy. Elwes's spare design shows the unelaborated power of the interaction. We witness the giving of strange or difficult news that demands from the giver words of reassurance and consolation.

Adam Wattam, writer

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy, Oxford University Press, 1972

Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy, Penguin, 1990

Sarah Drummond, Divine Conception: The Art of the Annunciation, Unicorn, 2018

Vernon Hyde Minor, Baroque and Rococo: Art and Culture, Pearson, 1999

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Early Modern Art, Jonathan Blower (trans.), Getty Research Institute, 2015