In a world saturated with images, it is difficult to imagine a time when all images were unique and limited to specific places. For centuries, such uniqueness restricted access to most images to the privilege of the wealthy and educated members of society.

The technological revolution of the fifteenth century, which introduced the printing press to Europe, combined with the increasing availability of cheap paper, enabled the exchange and dissemination of knowledge and images on an unprecedented scale.

James Northcote (1746–1831), Painting Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832)

c.1825–1830

John Cawse (1779–1862) (attributed to)

Johannes Gutenberg (c.1393/1406–1468) is all too often celebrated as the inventor of letterpress printing. Such a view is incorrect, however, as it completely ignores the history of text reproduction outside Europe. To understand the misconception behind Gutenberg's achievements, we must first clarify the meaning of printing and printmaking. The former is a process for the mass reproduction of texts and images using a master form or template, while printmaking describes the production of images or designs by printing from specially prepared plates or blocks.

Secondly, it is paramount to remember that the Chinese and Korean pioneers of printing were centuries ahead of Gutenberg by developing movable type made of clay or wood that could be printed on paper without a press.

Gutenberg replaced wood with metal for his movable type and applied the concept of casting, which saw letters created in reverse in brass and then reproduced from these moulds by pouring molten lead. He sped up the printing process by adapting a wine press to print text (and, later on, woodblocks), but he certainly did not invent printing.

Johannes Gutenberg (c.1393–1406–1468)

1895–1897

Robert Bridgeman (1844–1918)

Printmaking – the art of producing replicable images – began in China around the ninth century when pictures were produced through woodblock printing. In Europe, the history of printmaking had a very similar start, with images being produced using carved woodblocks, which, before the mid-fifteenth century, had to be hand-printed. That did not yield very satisfactory results in terms of quality, output and speed.

The introduction of the printing press around the 1450s allowed images to be mass-produced, making them easily accessible and affordable for the first time.

Two main printmaking techniques developed during the first three centuries in Europe: relief and intaglio, which used woodblocks and metal plates as surfaces, respectively.

Relief defines those printmaking techniques in which the printing surface is carved away so that the image alone appears raised on the surface. The raised areas of the printing surface are inked and printed, while the areas that have been cut away do not pick up the ink.

Intaglio works in the opposite way as the image is incised into a surface, and the incised line or recessed area holds the ink. Intaglio printmaking is closely linked to metalwork, goldsmithing, and the decoration of weapons and armour.

A silver footed salver, made 1762/1763

The transformative effect of printing technology on European art in the early sixteenth century was mainly driven by the influence of several seminal artists, most of whom originally trained as goldsmiths and applied the craft to the production of engraved and then etched metal printing plates.

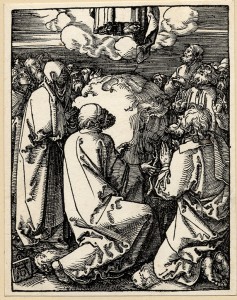

One of the leading artists of the printmaking revolution was the German painter and graphic artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Born in Nuremberg, he became one of the most famous artists of the Northern Renaissance. He created woodcuts, etchings and engravings depicting images of religion, history, mythology and portraits. Dürer was one of the first to become a truly international artist with his ability to produce visually appealing prints that were distributed throughout Europe. He produced many iconic prints, like Adam and Eve.

Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) (after)

The engraving shows the artist's fascination with the ideal form. Adam and Eve are positioned symmetrically in a dark German forest, diverging from the garden described in Genesis.

Adam, who resembles the Hellenistic Apollo Belvedere, reveals Dürer's exposure to ancient art seen through drawings. Dürer's mastery of engraving is evident in the intricately detailed human, snake, animal and tree textures. Symbolism abounds – the mountain ash symbolises the Tree of Life, and the fig the forbidden Tree of Knowledge.

The animals represent medieval temperaments, in keeping with Dürer's cultural pride and Italian influences, blending German identity with the classical tradition, evident in the classical figures and symbolism of the humours.

Another crucial artist for the development of printmaking techniques, and the spreading of inexpensive prints, was Lambrecht Hopfer (active c.1525–1550), son of Daniel Hopfer (1471–1536), the first artist to etch on iron to make prints. Lambrecht Hopfer made several accurate reproductive prints during his life, many of which after Albrecht Dürer's work, which made Dürer's popular prints accessible and affordable for everyone.

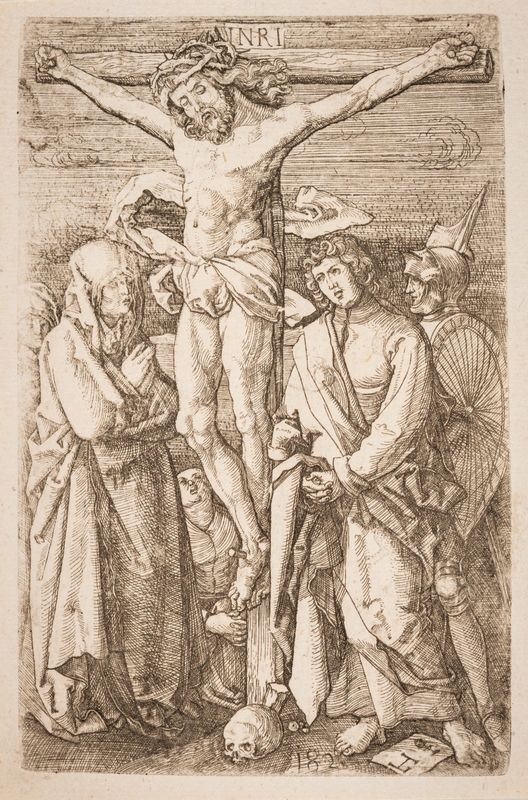

Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) (after) and Lambrecht Hopfer (active 1525–c.1550)

Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John is after Dürer's 1511 series 'The Engraved Passion', consisting of 16 plates. The original series was engraved, but Hopfer chose his family invention – etching – to copy the Crucifixion. That choice exploited established markets and helped to disseminate the Hopfers' novel technique.

Dürer produced his earliest known dated etchings in 1515, and that technique had become widespread by the next generation. Electing to reproduce an engraving of 1511 with an etching about ten years later proves the transformation of the emerging printmaking technologies.

The Temptation of Christ

1518, engraving by Lucas van Leyden (c.1494–1533)

Following Dürer, many other influential printmakers contributed to the advancement of the art. For example, Giulio Campagnola (1482–1515) was a trailblazer in the use of the stipple technique, which creates tone in an intaglio print using a pattern of dots of various sizes and densities across the image.

The Dutch artist Lucas van Leyden (c.1494–1533) produced large-scale prints that were innovative both in their content and technique. His prints are characterised by the use of fine lines and intricate cross-hatching to achieve texture and shading. Influenced by the humanist ideas of the Renaissance, Van Leyden incorporated classical and mythological themes into his prints.

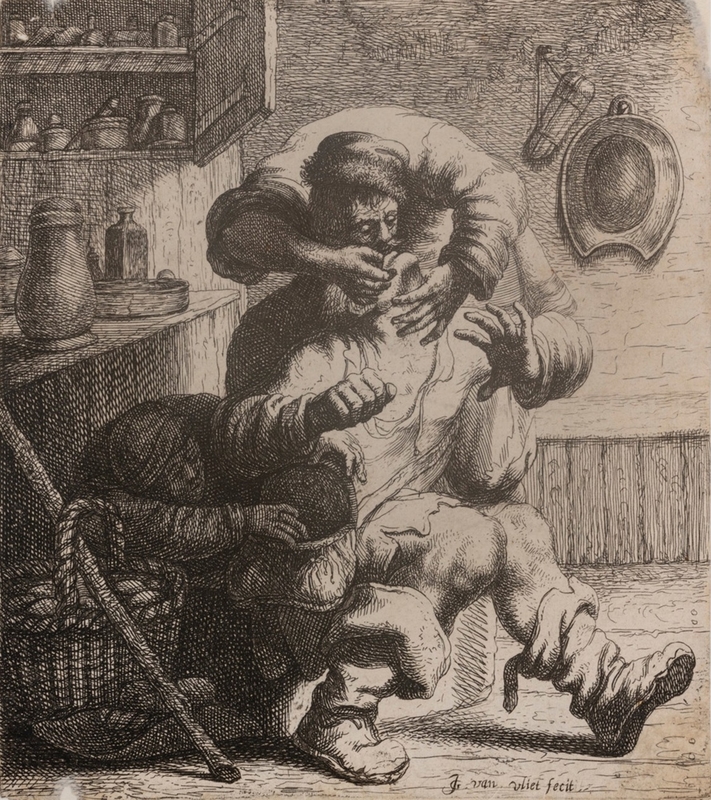

In the seventeenth century, the French engraver Jacques Callot (1592–1635) produced many series representing feathered nobility and ragged beggars, including the series 'Les Mendiants'. Callot was one of the first artists to depict the poor, demonstrating that peasants, Gypsies and beggars are important subjects. Callot's work influenced other artists, including Rembrandt, who admired Callot's skill with the etching needle and was inspired by these prints for his own images of beggars.

Untitled (woman holding stick and dish)

Jacques Callot (1592–1635)

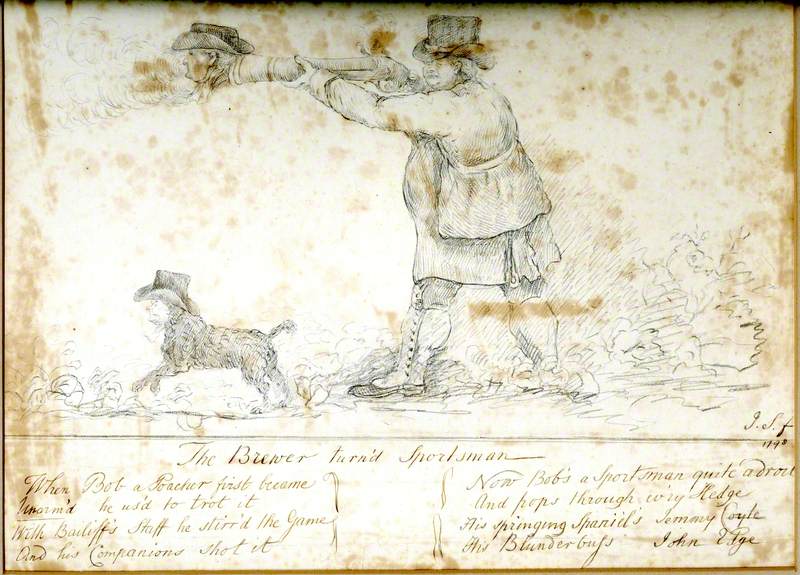

Many new printmaking techniques evolved in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including the development of wood engraving, lithography, photography and the means for introducing colour to prints. These advancements saw printmakers fully embracing the potential of prints as carriers of social commentary and critique to the masses, which had begun in the Reformation.

William Hogarth (1697–1764) championed this in the eighteenth century. Hogarth was aware of the role and impact that printmaking could play as an artistic medium. Therefore, he aimed to reach a broader audience by printing on cheap paper available in all London print shops. In this way, he appealed to a much wider market and allowed prints to become respectable works of art in their own right.

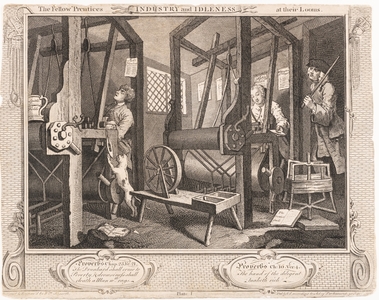

The Fellow 'Prentices Industry and Idleness at Their Looms

1747

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

His print, The Fellow ‘Prentices, is printed on inexpensive paper. It opens Hogarth's twelve-print series, 'Industry and Idleness'. The series tells of the contrasting paths of industrious and idle apprentices that shape their fate in later life. In this plate, the diligent apprentice works while the idle apprentice is confronted with the disapproval of his disgruntled master.

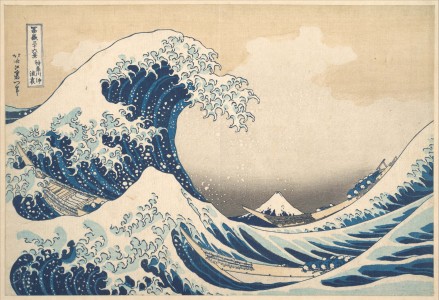

Significant developments in printmaking happened in Asia as well. From the late eighteenth century, it became possible to produce coloured single-sheet woodblock impressions. Coloured prints required multiple woodblocks that were printed in sequence to obtain layers of colour (nishiki-e).

The developments of colour woodblock printing in the eighteenth century laid the foundation for the golden age of ukiyo-e (a genre of Japanese art depicting everyday subjects) in the nineteenth century. Artists such as Utamaro, Hokusai and Hiroshige continued to expand the possibilities of colour woodblock printing and created masterpieces that were celebrated for their artistic quality and cultural significance.

Memorial Print of an Actor (shini-e)

Utagawa Kunihiro (1816–1860)

In the Edo period (1603–1867), woodblock prints usually depicted Kabuki actors and courtesans. They are characterised by bold lines and a rich colour palette.

The above print is an example of shini-e, a woodblock memorial print on a single sheet. The subject is the famous Kabuki actor Ichikawa Ebijuro I (1777–1827), who is depicted in a samurai's guise.

The print honours his acting achievements and conveys the sombre information of Ichikawa's passing in Osaka in 1827. Ichikawa was particularly skilled in expansive tachimawari (combat scene) and hayagawari (swift costume change) techniques.

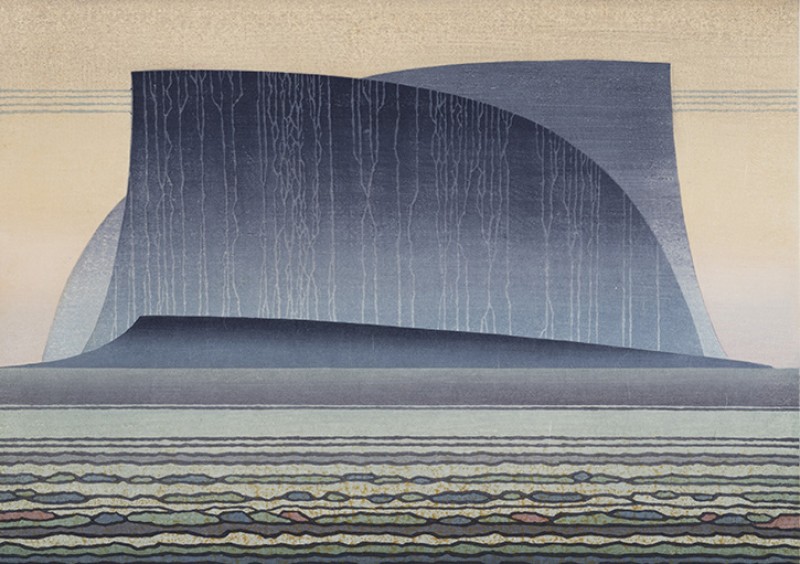

Since its dawn, printmaking played a crucial role in making art more accessible to a broader audience, breaking away from the exclusivity associated with traditional painting and sculpture. Although the use of printmaking to reproduce images of other works of art had become largely obsolete by the twentieth century due to the invention of photography, artists embraced this medium with renewed creativity, combining modern techniques with traditional forms.

Two Girls at the Printing Press

1900

Paul Berthon (1872–1909)

The reproducibility, lower cost and widespread distribution of printed images allowed printmaking to quickly become a powerful medium for conveying social and political messages, serving as a means of expression, protest, and activism well through the twenty-first century. The work of printmakers reached a broader audience and played a role in shaping the cultural and visual identity of their respective societies.

Chiara Betti, freelance curator and Collaborative Doctoral Partnership PhD student at the School of Advanced Study

RAMM's prints are part of the permanent collection and can be seen in their exhibition 'Pressing Images: prints from Exeter's fine art collection', open from 30th January 2024