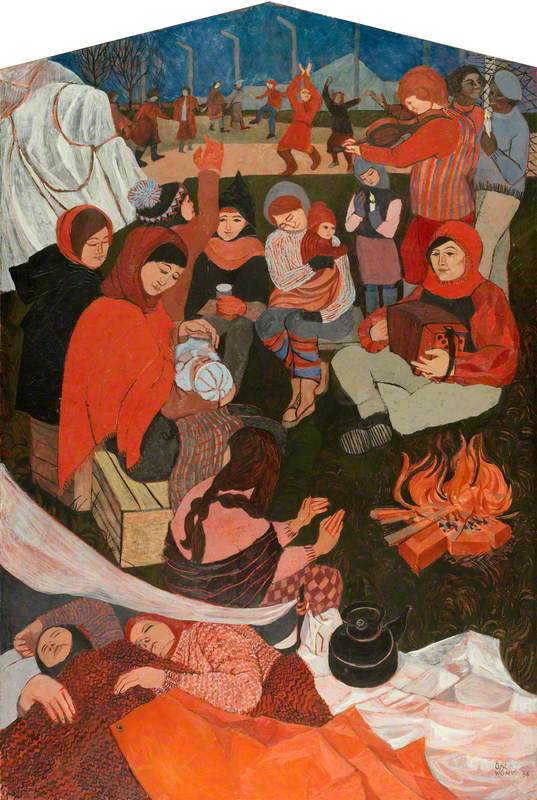

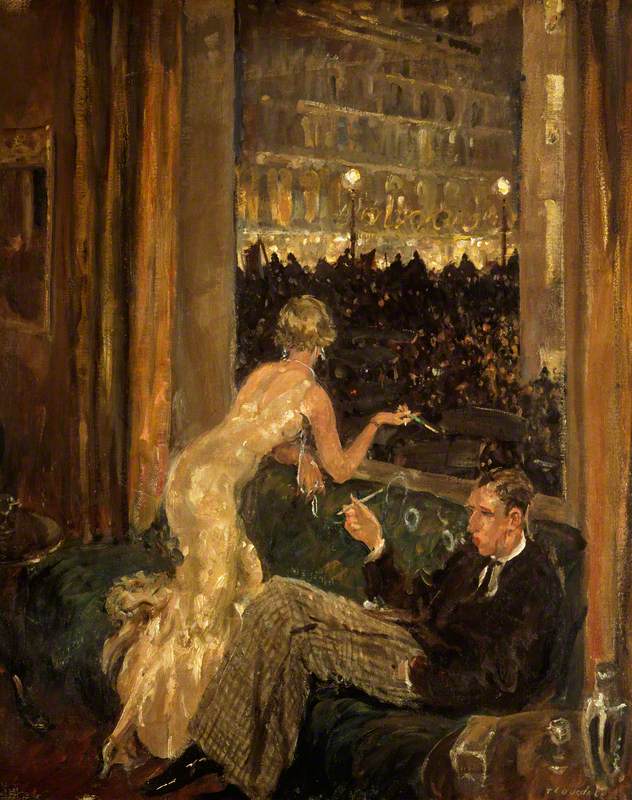

An upper-class couple sits at home, ensconced in gold upholstery. The woman wears a ballgown gilded to match, and looks out of the window to the mass of people gathered outside. She lets the ash fall from the cigarette in her holder while her partner sits unmoved, content to blow smoke rings and do very little else.

The Arrival of the Jarrow Marchers in London, Viewed from an Interior

1936

Thomas Cantrell Dugdale (1880–1952)

Over 85 years on, a group of people, perhaps a family, stand frozen in time on a pedestal in the middle of a Jarrow supermarket car park: their search for bread and labour immortalised in a location which offers plenty of both for as little as possible in return. The men carry a 'Jarrow Crusade' banner, emerging from the husk of the ribs of a ship, surrounded by work tools.

The Jarrow Crusade lasted three and a half weeks and covered 291 miles. It lasted through the wind and the rain, through sickness and exhaustion, through the Labour Party disowning the marchers at its Party Conference, through the Crusaders learning that their dependents' relief was being cut off since their providers were deemed to be shirking work. It lasted from Jarrow to Ripon, from Chesterfield to Northampton, from Bedford to Parliament, where, as Con Whelan, the last surviving marcher, said towards the end of his life, it didn't make 'one ha'porth of difference'.

And still, the Crusade remains a totem of British labour history. An opera, two musicals, three pop songs, five plays, and several works of art – the above included – have all been made in its honour. People taking the British Citizenship Test have been asked about it on more than one occasion. Graham Ibbeson's statue hints at why this is the case – his monument commemorates the Spirit of Jarrow: an elegy to the importance of will, the courage of action, and the impermanence of defeat. It stands as testament to the rest of Whelan's judgement of the march – that he enjoyed it every step of the way.

The Arrival of the Jarrow Marchers (detail)

1936, oil on canvas by Thomas Cantrell Dugdale (1880–1952)

Thomas Dugdale's painting, on the other hand, reduces this 'spirit' to shades of tan and ochre.

Little is known about Dugdale but the following: he was born in 1880 and schooled in London, Manchester and Paris. He worked as an artist in both World Wars and saw combat during the first. He was elected Associate of the Royal Academy in 1936 for his work as a portrait painter, then full member seven years afterwards. An entry in David Buckman's Dictionary of Artists in Britain since 1945 fleshes out his biography to include his work in textiles. He died in 1952.

Thomas Cantrell Dugdale

1900s (?) or 1910s (?)

Thomas Cantrell Dugdale (1880–1952)

It's intriguing, then, that for an artist apparently known as much for his textile design as for his oil portraits, here he skimps on depictions of both. Intriguing, too, that in a painting named for an unemployment march, he should do its members such a disservice. Interior and exterior are reduced to swathes of colour, with only the broadest strokes left to hint at the objects in the foreground – a curtain here, a cocktail shaker there.

The Arrival of the Jarrow Marchers (detail)

1936, oil on canvas by Thomas Cantrell Dugdale (1880–1952)

Nine times out of ten, these indications of wealth would be enough to let the viewer deduce who it is they're meant to be looking at, but here that doesn't seem to be the case. It's not uncommon for artists to depict the subjects of their portraits in a candid setting, but this couple's demeanour seems to cross the line from unstudied to uninterested. This isn't to say the painting is a portrait, but the focus is drawn away from the foreground. Its subject is a couple, but also a town – a murdered town, 291 miles away, called Jarrow.

Local MP Ellen Wilkinson coined Jarrow's mournful sobriquet in the title of her 1939 book, The Town that was Murdered.

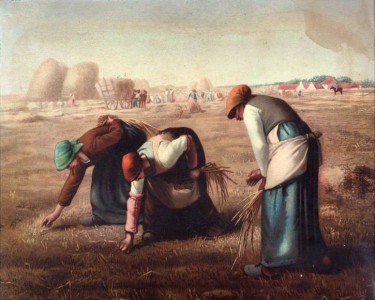

Margins at its shipbuilding yard, Palmer's, were suffering. Any of the benefits derived from cheap labour had been undercut by cheaper imports, and a crisis of overcapacity only made matters worse. In a bid to cut its losses, the Shipbuilding Employers' Federation established the National Shipbuilders' Security Ltd (NSS) in 1929, and charged it with the task of eliminating that excess. Working with the Government, the NSS closed 37 yards across the country. In 1933, Palmer's Yard became the 38th. Jarrow was one of the hardest hit areas: according to figures from the Medical Officer for Health, unemployment there skyrocketed to 80 per cent.

The Jarrow Marchers. Ellen Wilkinson is visible second from left

To add insult to injury, the NSS forbade any prospective buyer of the Palmer's site from reopening the works for at least 40 years, for fear it would encroach on the profitability of those berths which had been spared closure. It wasn't enough that the town had been summarily stripped of its largest employer: the government had worked with private interests to actively ensure nothing could be done to help those in the lurch. In July 1936, on one of the many occasions that town representatives brought a petition to the President of the Board of Trade, Walter Runciman, calling to reopen the works, their appeal fell on deaf ears. 'Jarrow', he told them, 'must work out its own salvation'.

Viscount Runciman (1870–1949), MP and President of the Board of Trade

1914

Reginald Henry Campbell (1874–1962)

The refusal, wrote Wilkinson, 'rekindled the town'. Hunger marches were relatively common during this period: records survive of at least three which took place simultaneously with the one in this painting. However, the people of Jarrow were keen to separate this march from the others, conscious of the ease with which the powerful dismissed them as Communist agitations. Jarrow's unemployed sought to promote a cause backed not just by a disaffected few, but by what Councillor David Riley described as 'the whole of the citizens... from Bishop to business man'. It was decided they would march to London in time for the reopening of Parliament and hand it a petition some 10,000 signatures strong to rouse – as Wilkinson later wrote – 'public opinion in England to plight of Jarrow, and the forgotten areas around it'.

Jarrow Marchers

So popular was the idea that more than 1,000 men volunteered to join a march that advertised only 200 places. Among their number were councillors from all three main parties: from the very start, selling the idea of the march as non-partisan was a priority. If the impression the marchers gave was too political, it was feared they'd be dismissed by Westminster forthright, and the 291-mile journey would have been for nothing. With this in mind, it was Councillor Riley who lent the word 'Crusade' to the banners which dominate the frame of nearly every photo of the march that survives.

Jarrow Crusade

Wilkinson presented the marchers' petition to Parliament on 4th November, a few days after their arrival. There, Runciman reiterated his previous statement and countered that the 'unemployment position' in Jarrow had actually improved: the efforts of a man named John Jarvis, High Sheriff of Surrey, who had offered private assistance to the town, acted as a sticking plaster on its open wound. After what essayist Ronald Blythe called 'a few minutes of flaccid argument', the discussion of Jarrow's ills was over. Wilkinson was told by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin that he didn't have anything to add to Runciman's statement.

Jarrow Marchers

This is the Crusade that Dugdale paints – its arrival in a city of indifference. Dugdale doesn't include any identifying feature of the marchers or their cause for the simple reason that they failed to register with anyone who was in a position to help them: all the viewer has to go on is the painting's title. Historian of the march, Matt Perry, cites a St Alban's woman's comment to the press as indicative of contemporary attitudes: 'I have tried to tell my friends down here how terrible things are in Jarrow but it's no use.'

Jarrow Marchers

Speaking to the Independent on Sunday in 1996, then-Deputy Director of the Museum of the Home, Christine Lumulia, recounted how viewers reacted to this visualisation:

'Most like it, admire its composition and what could be perceived as the artist's satirical comment on the class system; others vehemently dislike it, and are so overwhelmed with anger at the insolent wealthy couple that they are unable to enjoy the artist's overall achievement.'

Arrival of the Jarrow Marchers in London, 1936, oil on canvas by Thomas Cantrell Dugdale. The Leader of the House of Commons, 2019, installation by Jacob Rees-Mogg. pic.twitter.com/oLqMi3V1Eu

— Torcuil Crichton (@Torcuil) September 3, 2019

What the viewer is left with is a bleak image that could easily have been painted from memory – and could equally have been painted today. Matt Perry suggests that Dugdale himself saw the march from the top of a London bus – something that passed him by before receding into the distance, just as it does in his painting.

Jarrow Marchers

Though they were given a hero's welcome on their return, the marchers did so convinced of their failure. What they couldn't know then is the indelible mark they left on Britain's idea of protest, of how ordinary people could take on such immovable forces as government and industry.

The 'Spirit of Jarrow' which Graham Ibbeson depicts so poignantly can be felt in the creation of the welfare state after the war – it can be seen in the countless protests since 1936, successful or not. Its echoes can be heard in the campaign to secure food for malnourished children against the protests of government, by people like Marcus Rashford in the midst of the pandemic.

Dugdale was right to depict the faces of the marchers fading into the distance in his painting, 85 years ago. He was simply too early to know that by doing so, he himself was contributing to their immortalisation.

Jordan Butt, freelance writer and news producer

Further reading

Ronald Blythe, The Age of Illusion: England in the Twenties and Thirties, Penguin, 1983

Stuart Maconie, Long Road from Jarrow: A Journey Through Britain Then and Now, Ebury Press: Electronic Edition, 2017

Matt Perry, The Jarrow Crusade: Protest & Legend, University of Sunderland Press, 2005

Paul Perry, Jarrow Online, 2016

Betty Vernon, Ellen Wilkinson 1891–1947, Croom Helm, 1982

Ellen Wilkinson, The Town that was Murdered: The Life-Story of Jarrow, Victor Gollancz, 1939

.jpg)