Landmark birthdays often prompt reflections on life's big questions. For Glasgow-based artist Ilana Halperin, turning 50 brought bigger questions than most – because she shares her birthday with a volcano.

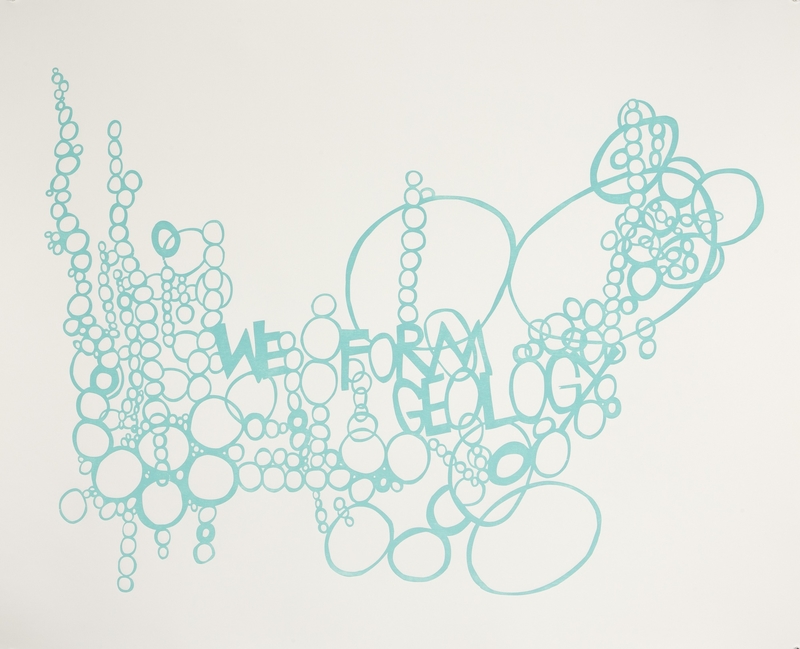

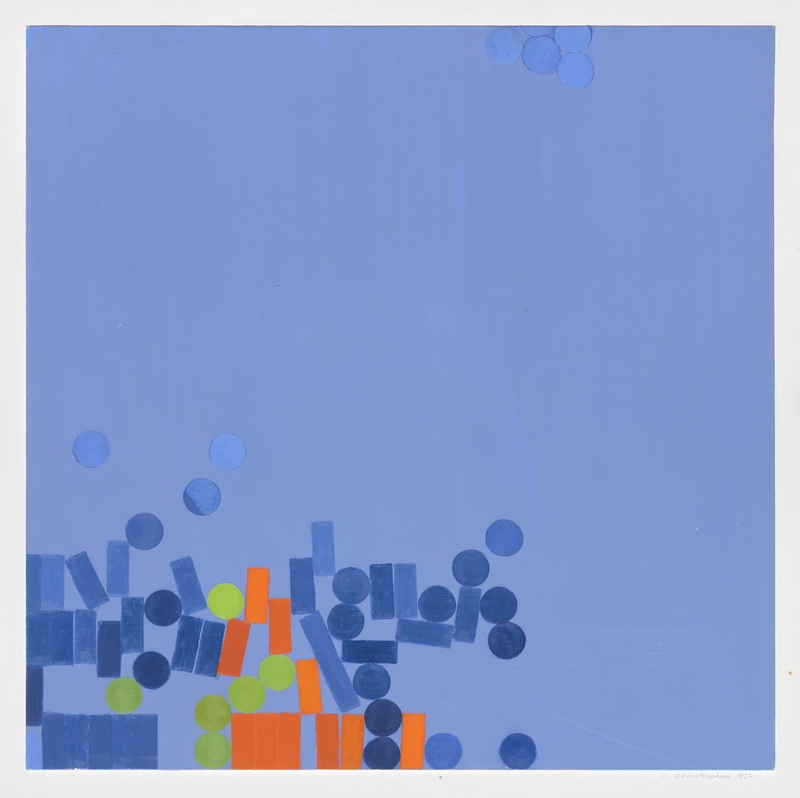

Twenty Years With Eldfell

2023, watercolour on Fabriano paper by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

When she spent her 30th birthday on the Icelandic island of Heimaey, where the Eldfell volcano was 'born' in 1973, the same year she was, she forged a link between them that is both personal and artistic. She returned to the mountain for her 40th, again making new work, and this year, turning 50, co-curated an exhibition on the island, 'A Meeting with Eldfell'.

'A Meeting with Eldfell' at Safnahús Vestmannaeyja

installation view of work by Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir and Ragna Róbertsdóttir

Her relationship with the volcano sits at the core of an artistic practice that has grown from her fascination with geology, and makes scintillating points of connection between the barely graspable aeons of deep time and the scale of a human life.

'What does it mean to share your life with a volcano? When you're 30, you're young, and so is the volcano. Forty felt different and 50 very different again. I hope I'm still here and can go at 60. What does 70 look like – what is 80?

'And what is the moment that the volcano continues in a lifespan that is no longer human – is that 150 or 800 or 800 million? What does it mean to think about your own lifespan in the context of something that will live much, much longer than any of us will?'

Ilana Halperin

She recalls an article by a favourite author, John McPhee, in which he asks geologists how humans can comprehend deep time. 'They say, well, they may not be able to comprehend it, it's just too big. In a way, my practice is a way of intervening in that to say, no, there are these moments when we can comprehend it, by finding these tiny points of contact or commonality between people, places, processes – things that we would not under normal circumstances place together.'

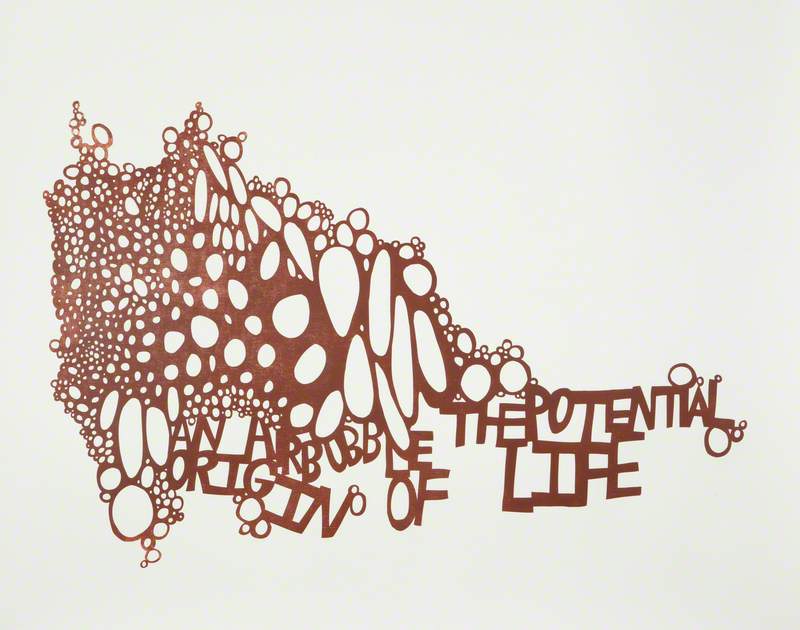

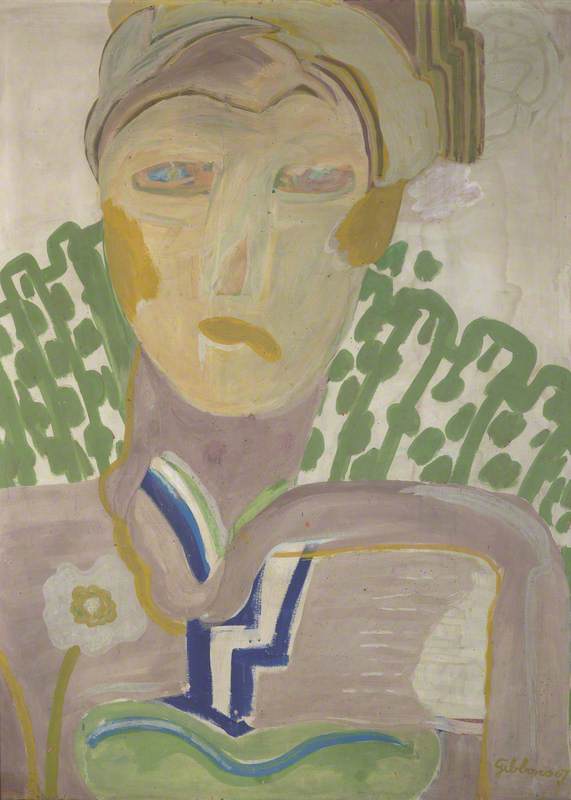

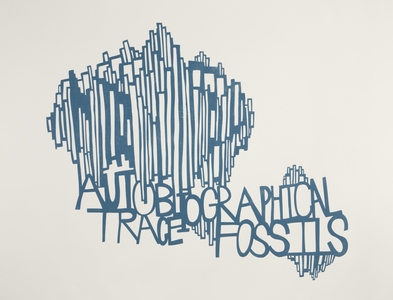

A Geological Meeting Between I. H. and H. I. (An Archaeology of Barts)

2010

Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

Talking with Halperin, wonders leak out into the conversation: a lump of garnet the size of a grapefruit found under the streets of Manhattan; a meteor older than the Earth; the fact that tectonic plates move at the same rate as human fingernails grow; the tracks, etched in rock near St Andrews, of a 10-foot-long prehistoric centipede.

Halperin grew up in Manhattan, loving from childhood the Rock and Mineral Halls of the city's American Museum of Natural History. Leaving New York's High School for the Arts, where she majored in sculpture, she got an apprenticeship at a stone-carving supply store in the East Village, where she was paid in rocks. After a wide-ranging undergraduate degree at Brown University, Rhode Island, she came to Scotland in 1998 to study on Glasgow School of Art's MFA course.

It was while at GSA that she discovered Eldfell. 'I just thought, "I want to go there for my 30th birthday", I didn't know why. Afterwards I understood that it was to do with the impending death of my father (who was terminally ill with cancer at the time). It grew out of grief and a desire to think about new possibilities of what family means, trying to think more expansively about time and mortality and how we're situated in this cycle of life, whether earth, human, animal or mineral.'

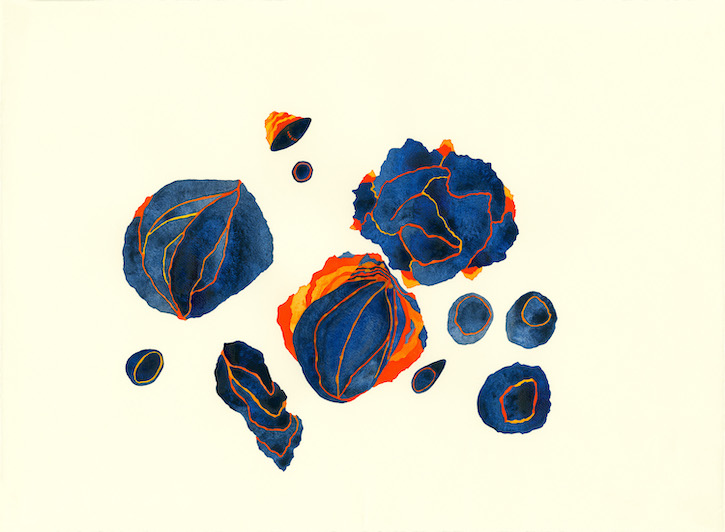

Self Portrait as a Lava Bomb

2023, watercolour on Fabriano paper by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

Approaching her 50th birthday, she felt very different. 'When I went to Eldfell at 40, I was still trying to have a child. I was thinking, "Will I get to bring my child at 50?" I did not think that my mother would be gone (she died in 2020). This time last year, I was thinking: "I will go to the volcano and it will be so sad! How can I flip that feeling into something extremely life-full?"'

That prompted a generous impulse to find other artists, writers and scientists who had worked on Eldfell. A core of four – Halperin, co-curator Vala Pálsdóttir, anthropologist Gíslí Pálsson and artist Þorgerður Ólafsdóttir (who graduated from GSA a decade after Halperin) – grew into a group of 20 people from all over the world.

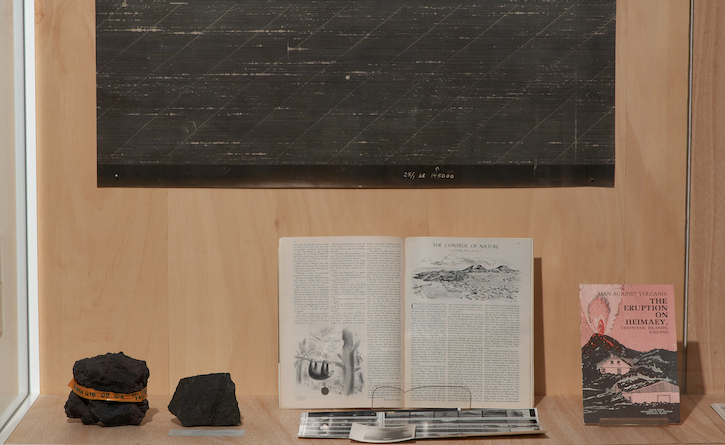

As well as co-curating, Halperin made new work for the show, which also included scientific material: core samples of lava, a seismograph of the volcano's first 'birthing' movements, and a rock from a 'sister' volcano, Nishinoshima in Japan, born the same year.

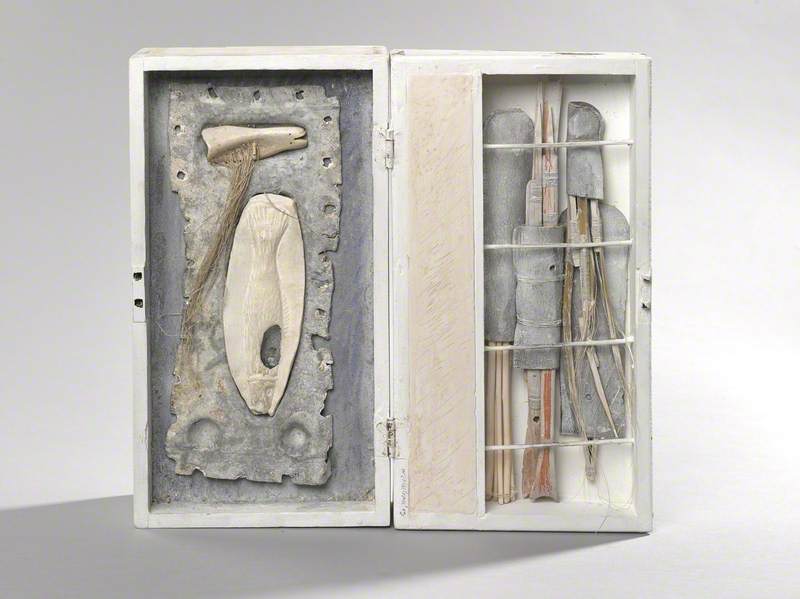

'A Meeting with Eldfell' at Safnahús Vestmannaeyja

(detail), installation view of archive case

'In a way, it felt like I was making a dream show, to be able to invite other people in, to be able to bring Nishinoshima to Eldfell, to reach out to John McPhee (now 92, who wrote a short essay). It's a wishlist of all the things I'm passionate about and to be able to bring it all together in one place felt like a miracle. It was a beautiful, powerful, tender exhibition.'

If there is one word which describes Halperin's approach to art-making, it might be 'tender'. Whether working in drawing, watercolour, printmaking, film, sculpture or performance, everything she does is considered and thoughtful, often the product of long research or long collaboration with scientists. While it's often beautiful, it tends to be unostentatious; works are often small, but address the biggest of themes.

Her approach and her integrity have earned her respect in the fields of both art and geology, and opportunities to work in some of the geological hotspots of the world, from the UNESCO Geo Park of Haute-Provence, to Japan, Hawaii and Iceland.

Her work has been shown at galleries and museums around the world, from San Francisco's Exploratorium to her 'vast' exhibition in 2012, 'Steine', at Berlin's Museum of Medical History, which considered body stones as new land masses made by and within the human body. A book of essays about her work, Felt Events, was published in 2022.

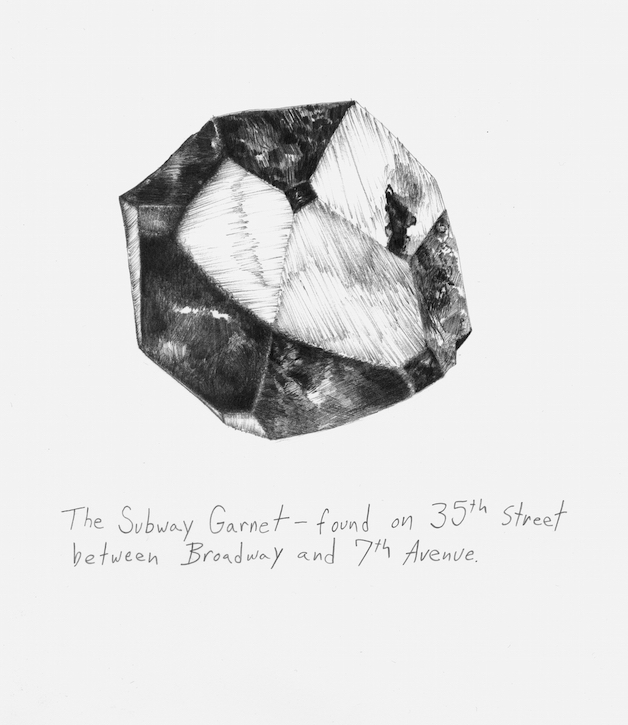

In 2012, she returned to the Rocks and Minerals collection in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, taking time over five years of visits to look at the extensive collection of samples. 'I knew I was moved by looking at these minerals which were born in the same place I was, but I didn't know what it meant. Then, on one visit, I came across a piece of garnetiferous gneiss from 87th Street and Broadway, and everything clicked into place. I was born on that block, where this piece of rock was found 150 ft below the sidewalk.'

The Subway Garnet

2012, graphite on Fabriano paper by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

Returning to the drawers, she found a further 17 minerals that correlated with her personal geography: her elementary school, her first studio, the hospital where her father died. Stones became connections to memory and imagination, a way into thinking about her relationship with the city, its cultural history, and her own family's history.

'Minerals of New York' was shown at Leeds Arts University and then at The Hunterian in Glasgow in 2019, and has just been shown by Glasgow's Patricia Fleming Gallery at the New Art Dealers Alliance (NADA) on Governor's Island, New York. 'It's been quite a dream to mine to bring that work home, you could say, to put it in a New York context where people have very different histories and relationships to all of those places.'

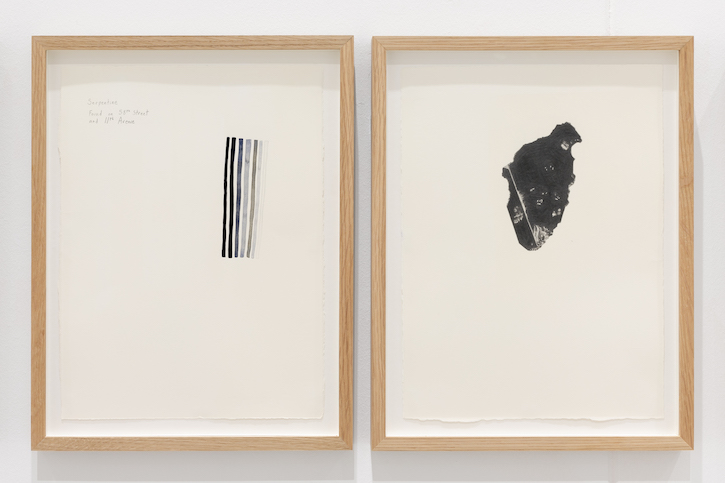

Serpentine I & II, 58th St and 11th Ave

2018, graphite & watercolour on Fabriano paper by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

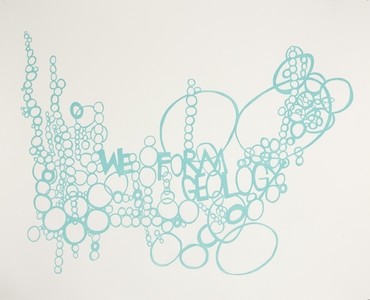

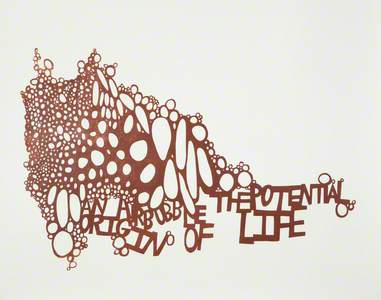

She has realised, looking back on two decades of art-making, that the intertwining of the geological and the personal, which she calls 'geologic intimacy', is one of two strands in her practice. The other – 'physical geology' – is 'more corporeal, more abstract, more sculptural', involving making sculptures through living geologic processes such as the calcifying springs at Fontaines Pétrifiantes in the Auvergne or mineral-rich geothermal pools of Iceland's Blue Lagoon.

The Rock Cycle (installation view at Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute)

2021, bricks & drainage tiles encrusted in limestone deposits by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

'These two strands of practice sit alongside each other, maybe asking the same set of questions but manifesting very differently. Both approaches are very important developmentally because they allow the work to go where it needs to go, they allow me to follow different strands and unexpected paths within the working process.'

Recently, for example, she has completed a commission, Chaos Terrain, for St Andrews University after working for a year alongside scientists in the School of Environmental and Earth Sciences (SEES). It is, she says, her favourite way to work: 'An open exploratory process where we don't know what it might lead to. There can often be a pressure where people say, "You're working with these scientists, are you going to make the work that they do more transparent to the public?" That's important, but I like not to do that, I want whatever develops to come out of genuine contact and the opportunity to spend time with people from different disciplines.'

Chaos Terrain brings together Ledmore marble, quarried in Scotland, with coral grown in a St Andrews laboratory and cave-cast in limestone in the Fontaines Pétrifiantes. 'So it's a piece of work composed of materials with all these different lifespans, from 500 million years old to three months old, but all related to calcium carbonate life forms, of which we are also one.'

The Rock Cycle (installation view at Mount Stuart, Isle of Bute)

(detail), 2021, bricks & drainage tiles encrusted in limestone deposits by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

And that's the core of it, perhaps, the realisation in the gut that one is made of some of the same materials as the Earth's earliest life forms. It's a thought that connects us intimately to our world, not only in the past but in the present and the future.

Halperin says: 'For people who are making work in relation to climate crisis, there can be a pressure that the work needs to look like an activist practice. I would say, as a queer feminist land artist, my work is, of course, embedded in an activist practice, but in an intimate and gentle language that helps facilitate different ways of connecting to things.

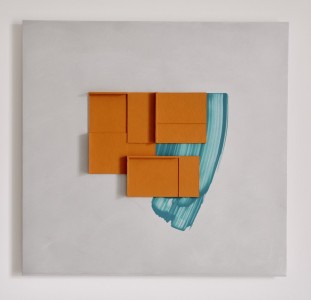

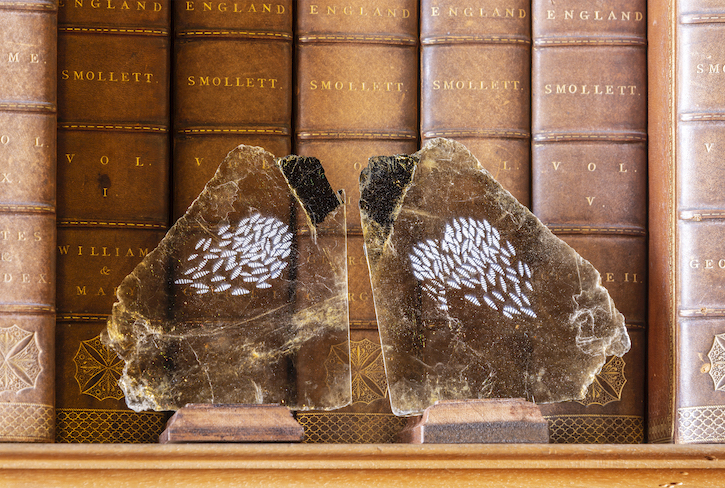

The Library

(detail), 2020, artwork by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

'It's interesting the conversations I've been able to have with people using Eldfell as a framework. It becomes a very relatable way of talking about difficult and big questions about how we live our lives. What does it mean to share your life with a volcano? What does it help us to think about? If Eldfell is my sister and Nishinoshima is another sister, that means my family is going to live a really, really long time. How do I help look after my family?'

Susan Mansfield, writer and journalist

This content was supported by Creative Scotland