The first thing to consider is – can we define drawing as a medium? What separates it from painting, for instance? Or other works on paper – prints, collage or photographs? How does it relate to sculpture, installation, video or conceptual art?

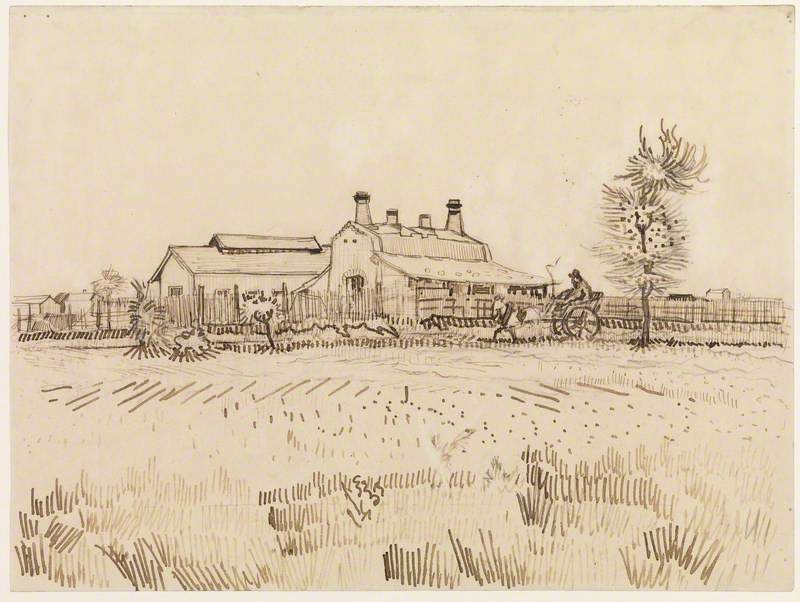

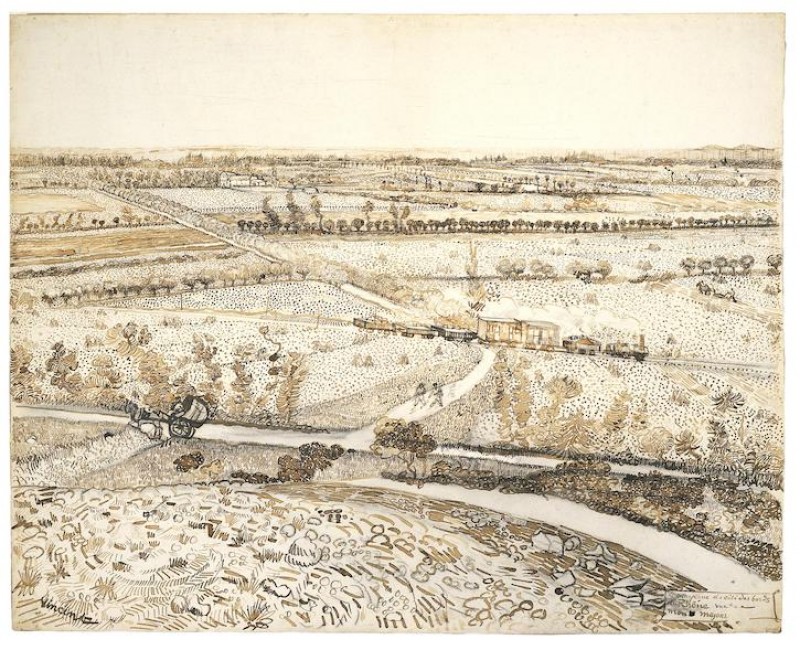

The simple answer to these questions, in Vincent van Gogh's powerful phrase, is that '…drawing is the root of everything.' For artists across all media, drawing is the basic starting point – an expressive medium on its own – as we can see in Van Gogh's drawing of 1888. But drawing can also serve as a bridge between creative thought and a larger realisation.

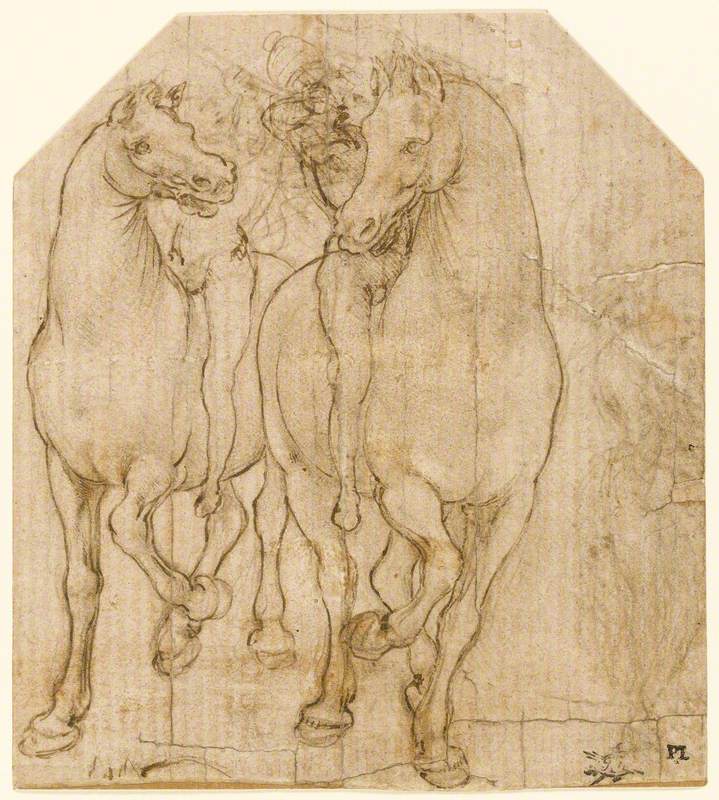

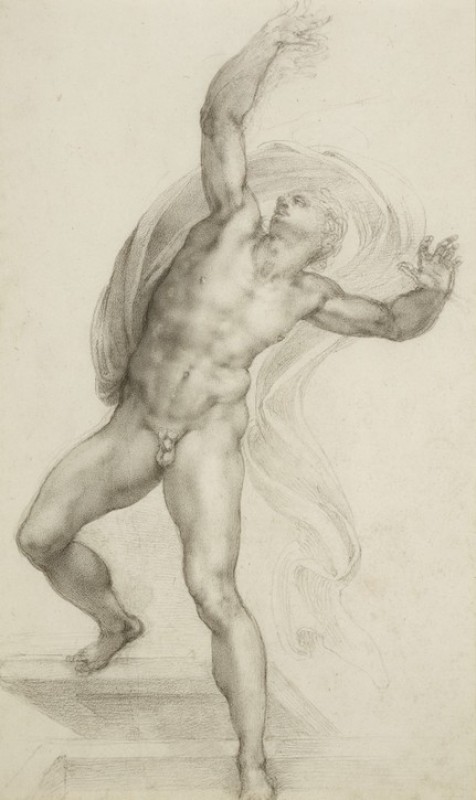

The act of drawing runs right through the history of art, often representing an artist's most direct and exhilarating work – Leonardo da Vinci's studies, for example, such as this wonderful depiction of two horsemen – which continue to fascinate and delight audiences around the world.

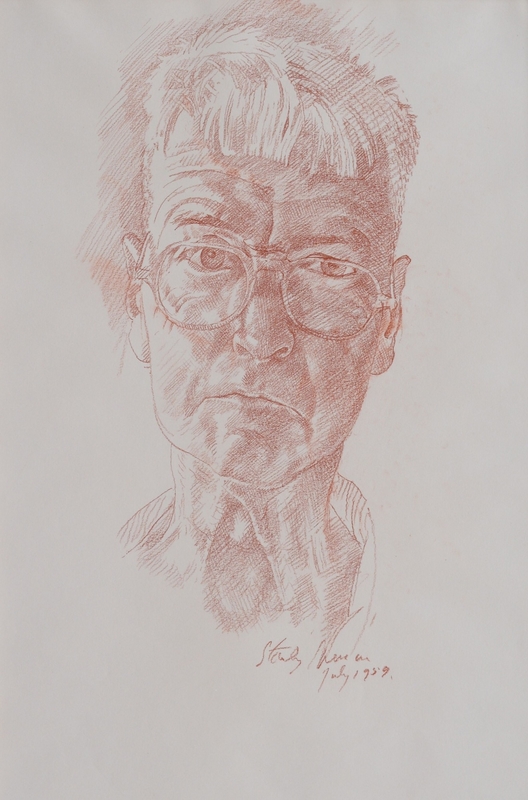

Another important consideration when curating a show of drawings is to ensure that very act of showing them does not aid in their destruction. Drawings, along with watercolours and other works on paper, are often very fragile and can be especially sensitive to light. Paper that contains too much wood pulp (such as newsprint) and colours that are 'fugitive' – most usually reds, browns and yellows – will discolour or fade quickly when exposed to light. There is no easy way of arresting this deterioration and prevention means keeping them permanently in the dark.

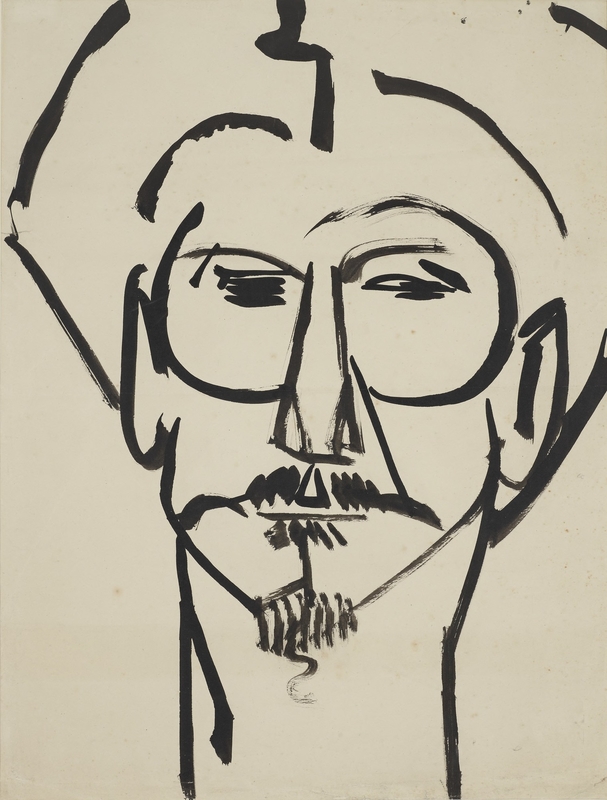

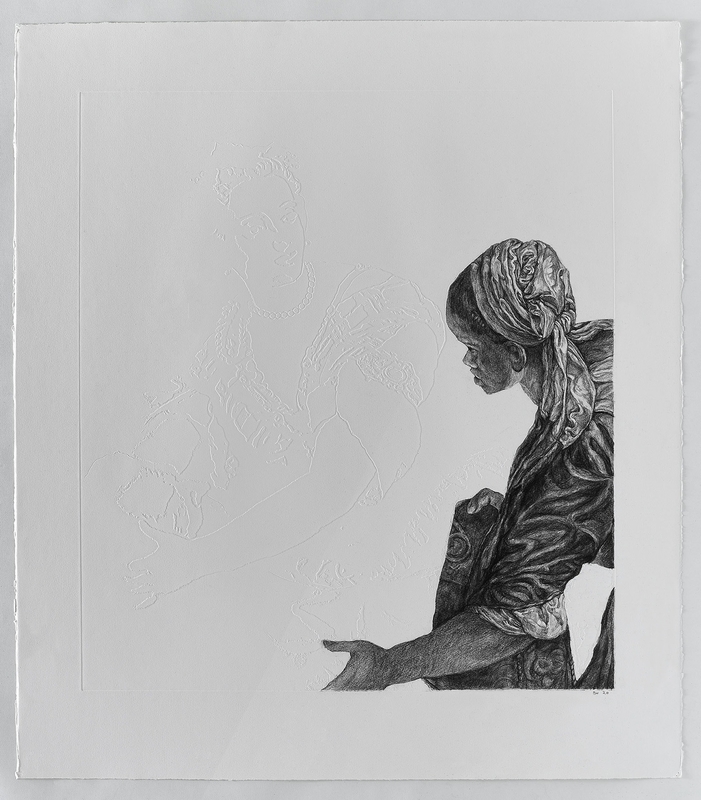

The simple answer is to ration exposure to light. In practical terms, this means keeping the blinds down in the gallery and dimming the lights to the lowest possible viewing level. Following exhibition, drawings are often 'rested,' further restricting their hours of exposure to light. For example, at the end of the British Museum touring exhibition 'Pushing paper: contemporary drawing from 1970 to now' (which was co-curated by The Pier Arts Centre, Orkney and presented there in 2022) the drawings were all returned to their light-tight storage in London.

'Pushing paper: contemporary drawing from 1970 to now', 2022

The Pier Arts Centre, Stromness

Preventative conservation can also help prolong the life of fragile drawings, making them more robust for exhibition. Many older drawings are framed with cheaply produced mount card and hardboard backing which inevitably leads to discolouration. This gets progressively worse over time, whether exposed to light or not. An immediate remedy is to place an impermeable barrier between the work and the offending material. Better still is to replace the mount and backboard with acid-free alternatives. This will prevent any further deterioration and provide a good environment for the drawing's long-term survival.

Once the care and conservation of the works has been addressed, the exciting question of creating a group of works that will hang well together is the next thing to consider. The Pier Arts Centre's collection contains a selection of fine drawings and the three works described below offer a variety of methods, with strong threads that connect the artists and their work.

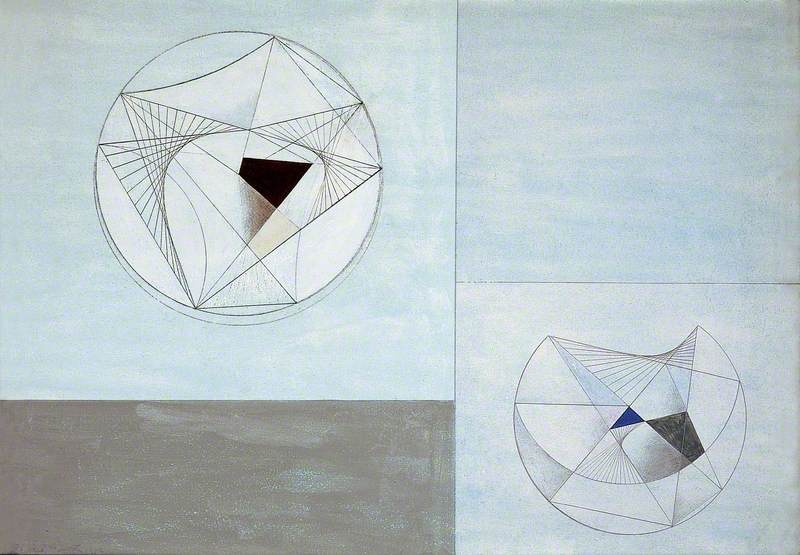

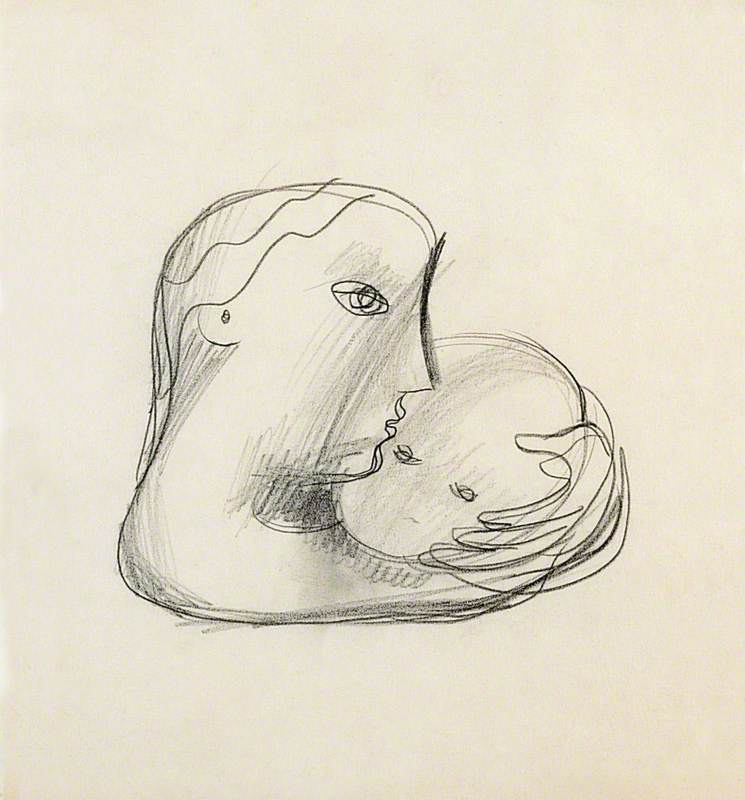

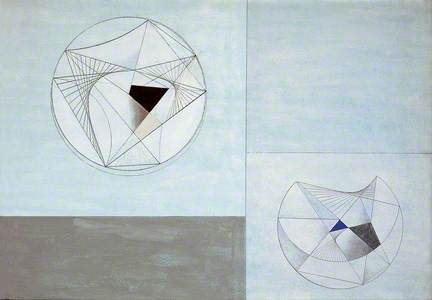

The English sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975) made many studies and plans ahead of committing to three-dimensional form. Drawing for Sculpture was made at a time when Hepworth was unable to work at scale – the progress of the Second World War severely limiting the time and resources available to the artist. Drawing became a way to develop ideas on paper, to be transformed into three dimensions when circumstances improved: a signal of hope that war would eventually end.

By simple means, Drawing for Sculpture explores a theme the artist had been concerned with for some time. The mathematical analysis of shells and other natural forms was a prominent area of study for Hepworth and other artists in the 1930s and 1940s. The theories of the Scottish biologist D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson (1860–1948) helped artists to visualise the natural world in new ways that reflected an interest in science, as well as art. Drawing for Sculpture takes a pair of circular forms and defines various concavities and divisions through line and colour. The horizon line, suggesting a notional landscape, gives the two forms some weight, making it easy to imagine how they might be expressed in sculptural form.

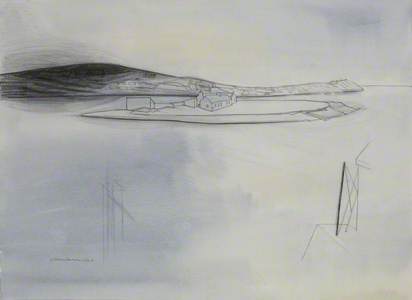

The relationship between drawing and painting was a little different for the Scottish artist Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004). Take a work like From The Pier Arts Centre, Stromness (Blue), which shows the Holms of Stromness from the upper floors of The Pier Arts Centre where the artist stayed for a few weeks in 1983. The drawing is not a stepping-stone to a painting but rather a complete and fully realised work in its own right. Drawing is 'a discipline of the mind,' as the artist put it, and was fundamental to Barns-Graham's understanding of the world. Like Hepworth, Barns-Graham had a deep interest in the work of D'Arcy Thompson, which helped inform Barns-Graham's understanding of form and structure.

From The Pier Arts Centre, Stromness (Blue)

1984–1986

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004)

From The Pier Arts Centre, Stromness (Blue), is one of a series of works of the same subject that the artist clearly used to pin down memories of the place. The drawings and observations that Barns-Graham made on the spot in Orkney would feed into many Orkney-inspired works by the artist.

The third artwork highlighted in this story is by the Orcadian artist Sylvia Wishart (1936–2008). In common with Hepworth and Barns-Graham, Sylvia Wishart regarded observational drawing as the cornerstone for all her work. Not long after graduating from Gray's School of Art in Aberdeen, the artist embarked on a series of over 40 drawings of the Orkney landscape that would become one of the finest topographical studies created anywhere in the UK.

View this post on Instagram

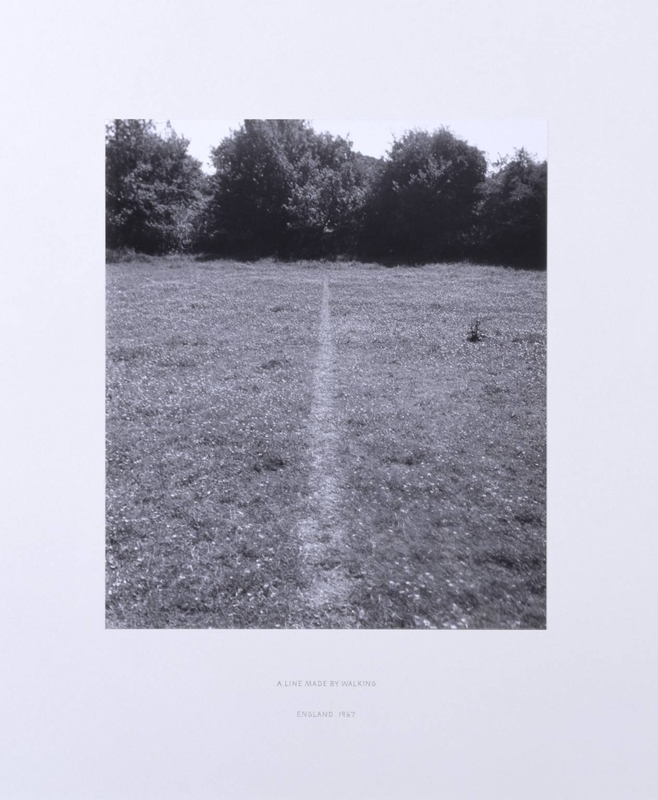

The 'Calendar Drawings' (so called as they were produced for a Kirkwall agricultural merchant's annual trade calendar), created by Wishart between 1968 and 1977, combine acute and direct observation with an intuitive sense of framing, elevating local subjects including piers, mills, castles and churches to a sublime and universal beauty. They are now in a private collection.

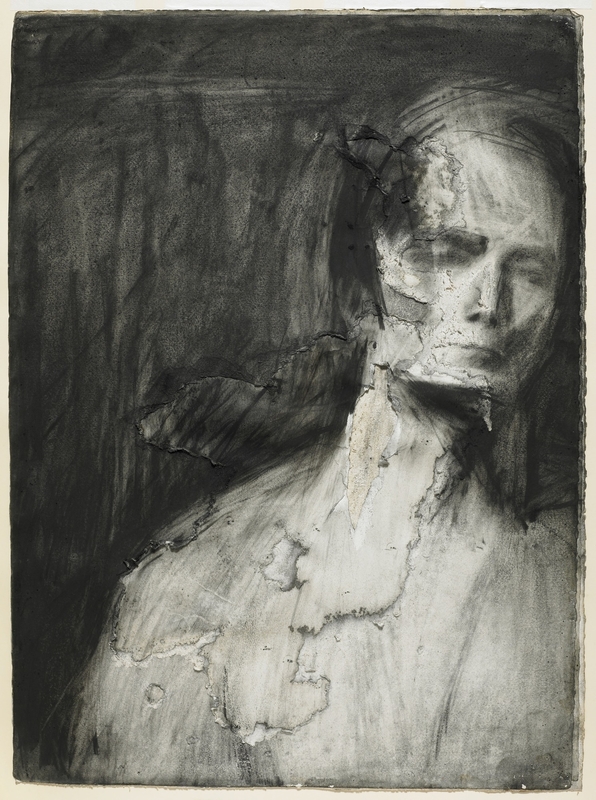

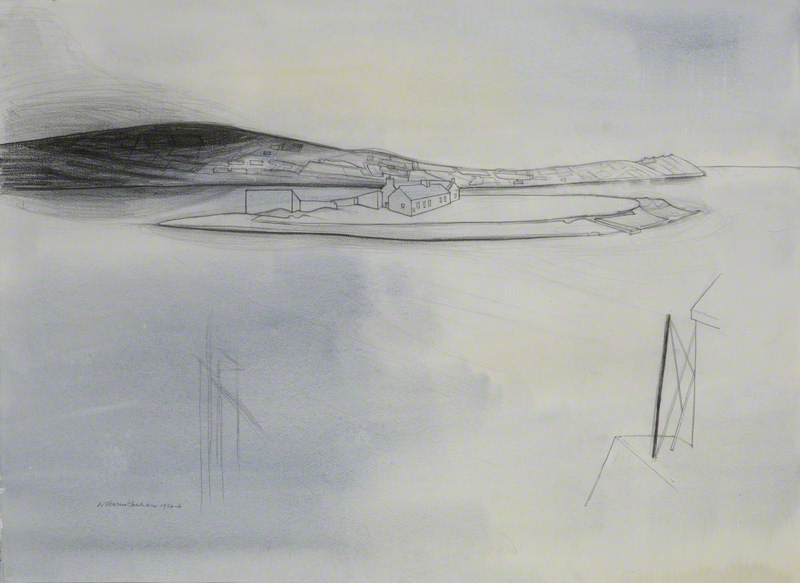

This series of exquisite drawings would eventually give way to a sequence of large-scale works on paper that fused her interest in drawing and painting. Hoy Sound depicts the view from the artist's house, Heatherybraes, looking across to the island of Hoy and the often ferocious tides of the Pentland Firth beyond. Wishart moved to Heatherybraes, just outside Stromness, in 1978 and the view from her 'picture' window became the sole subject of her work. From an elevated position, Wishart observed and recorded this changing panorama in a remarkable series of large-scale works on paper. The catch-all phrase 'mixed-media' serves to describe Wishart's practice.

Hoy Sound, along with 20 or so related works created over the last decades of Wishart's long career, represents a remarkable artistic achievement. The artist's unusual working method offers an insight into her daily routine: 'Over the past 15 years or more my method of composing has been to pin on the studio wall a large sheet of very rough, durable paper (up to 8ft by 4ft). Starting in the central area (not necessarily the centre) I will let the picture 'grow' in all directions until a decision is made where to stop the image. Hopefully I will not run out of space!'

Sylvia Wishart would take weeks or even months to complete a picture. All sorts of images gathered from sketching through the window come together in a composition that is a reflection on time passing as well as a unique record of one of Orkney's most striking landscapes.

While the traditional categories of drawing, painting, sculpture, film, etc., can be a useful shorthand, they more often than not provide unnecessary boundaries that most artists tend to ignore anyway. Curatorial distinctions are there to be blurred and the beauty of drawing rests in the simple means required to make them, whether with a reed pen on a sheet of paper, experimenting with sculptural form, setting out a visual memory or attempting to fix the passage of time.

Andrew Parkinson, curator at Pier Arts Centre

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Mel Gooding, A Discipline of the Mind: The Drawings of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, The Pier Arts Centre & The Barns-Graham Trust, 2009

Isabel Seligman, Pushing paper: Contemporary drawings from 1970 to now, British Museum, 2019