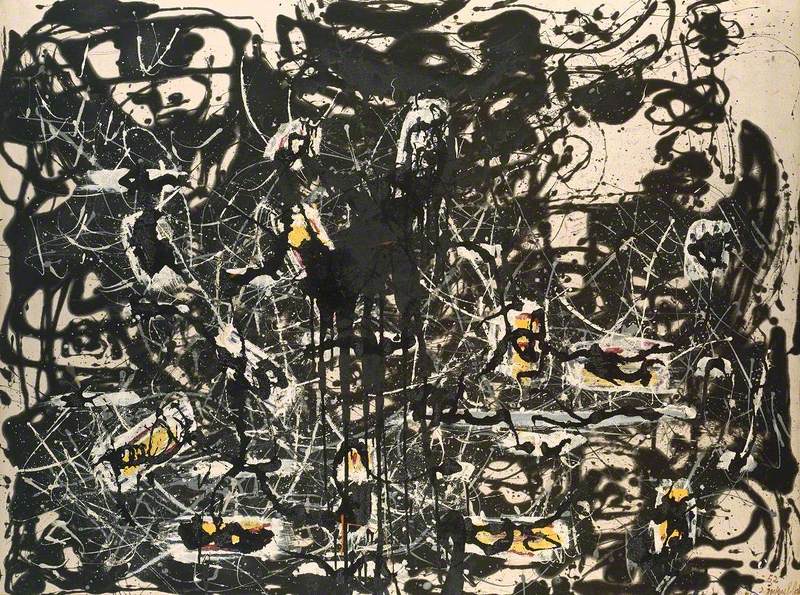

North America as a continent is often imagined to be a 'westernised' area of the world. In the UK, when we imagine American art we might immediately think of Jackson Pollock or Andy Warhol. But if you were asked to think of Indigenous American art, you might struggle to conjure an image in your mind, or would imagine the type of wood carvings that have been portrayed more often in popular culture, such as these colourful totem poles.

Kakaso'Las Totem Poles

1955, carved by Kwakwaka'wakw artist Ellen Neel (1916–1966)

These assumptions are totally dismantled by the reality of the contemporary North American art scene, which is full of exquisite works by Indigenous people that enlighten our understanding of the continent's culture. The works of Canada's First Nations people and those of the United States' Native Americans show distinct differences – however, this article will consider in more nuance the contemporary tribal art from both.

Susan A. Point

Already highly recognised with multiple honorary doctorates and an appointment to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, Susan A. Point represents a huge influence on First Nations art in Canada and internationally.

Susan Point

A Musqueam artist, Point's work is interested in reviving the traditions of Coast Salish art. She undertakes much of the teaching and research into the history of her region herself, as it has been largely neglected and under-researched. Referencing and inspired by Coast Salish history, Point's work also reflects the present state of its culture. Her strength is the flexibility of her work, which uses a wide variety of techniques and materials, from concrete to glass.

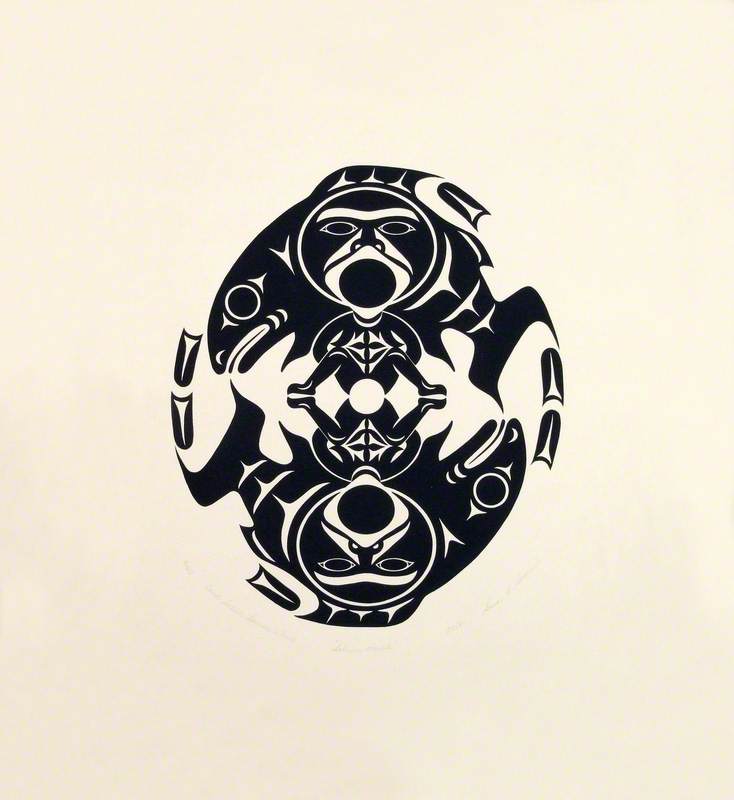

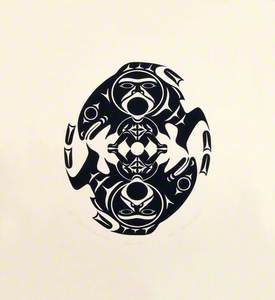

As seen in Salmon People, Point is particularly interested in the variations of traditional Salish Coast spindle whorl carvings. Spindle whorls are the discs on spindles that quicken their speed in order to prepare wool. In Salmon People, the circular shape of the whorl, as well as the central hole, are echoed in the shape of the print. The direction of the salmon creates a sense of the movement of the whorl, as if it spins before our eyes. Point builds upon this historical-cultural influence, but this screenprint is also very contemporary in terms of technique and medium.

Timeless Circle

2013, by Susan A. Point (b.1952)

A contemporary spark is seen again in Timeless Circle. The spindle whorl shape is present, but this time is made up of multiple overlapping circles. Circles and crescents are a strong part of Salish cultural patterning, and again Point utilises this circular language to refer to the past within her contemporary work. The diversity of the faces – that appear in multiple colours and tones – reflects the diversity of contemporary cultures and ethnicities in the US, inviting the audience to rethink assumptions about a 'white' North American identity.

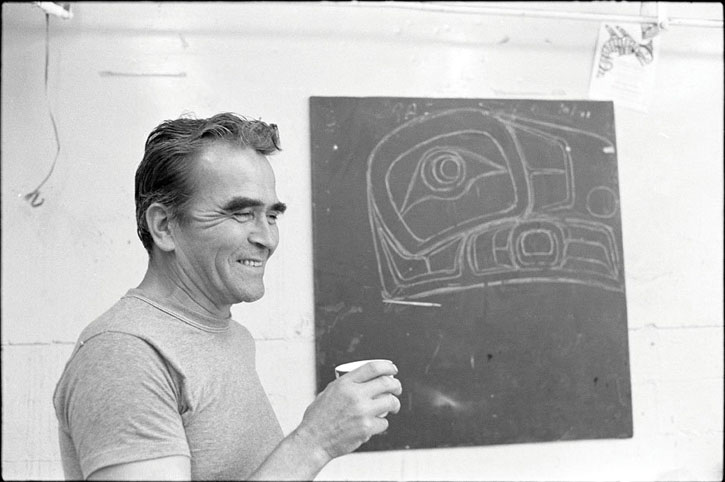

Doug Cranmer

Also known as Kesu' (meaning 'wealth being carved'), Doug Cranmer began his life in the fishing and logging industry, before becoming a carver. From his father, he inherited the position of 'Namgis chief, therefore adopted the name of Pal'nakwala Wakas, meaning 'great river of overflowing wealth'.

Doug Cranmer

1980, photograph by unknown artist

He was schooled in the traditions of his Kwakwaka'wakw heritage and later established a commercial gallery, Vancouver's The Talking Stick, which became one of the few galleries at that time through which First Nations art was marketed by First Nations people. Like Point, he worked with a variety of techniques such as carving and printmaking, but always shunned the limelight and referred to himself only as a 'whittler and doodler'. Despite his humility, Cranmer's influence upon Northwest Coast contemporary art is huge, as he took the traditions of his people and modernised them.

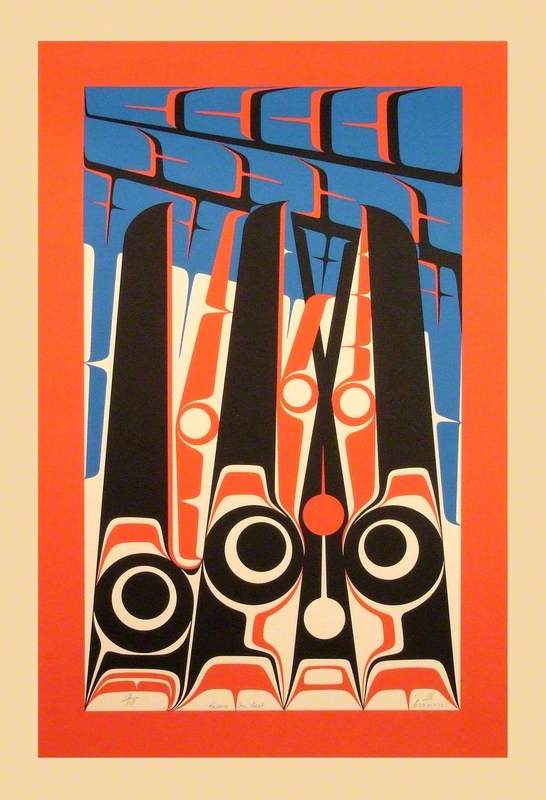

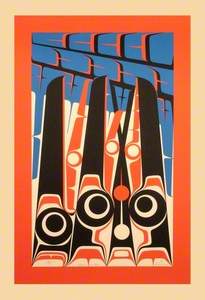

In this print, Cranmer's abstract tendencies reveal themselves, aligning his work to the aesthetic of western abstract art. The individuality of this contemporary piece lies in its homage to the past, but simultaneous alteration of tradition. The U shape, traditionally found in Northwest Coast Indigenous art, is used repeatedly across the top of the print, while the core colours of Indigenous art – usually black, blue and red – flourish across the page.

Cranmer was known for his desire to be different, and yet his cultural history is never abandoned. This is what the art world would call a hybrid piece: one that takes from both tradition and modernity.

Norman Tait

The son of a carver, Norman Tait was a Nisga'a First Nation artist from Canada, who created the 55-foot totem pole named 'Big Beaver' at the entrance to the Field Museum in Chicago. Like Point, he found early on in his career that there existed little to no research on his people and their artwork – as well as few living artists to learn from. Instead, Tait learned through oral histories and storytelling: forms of education and history that pervade Indigenous culture across the globe.

'Big Beaver' totem pole, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago

1981–1982, carved by Norman Tait (1941–2016)

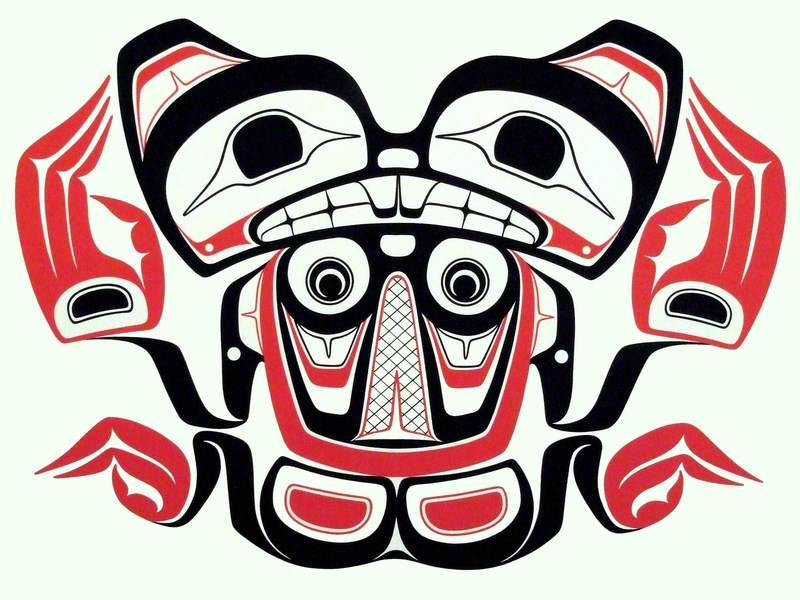

In Nabibeh (Beaver), Tait explores the form of the beaver that he also depicted on the Field Museum's Totem Pole. The beaver is the symbol of the Nisga'a, and takes part in many stories that explore the Nisga'a's heritage and ancestry.

Like Cranmer, Tait depicts the beaver in a more abstract way, hinting towards the stories of his people through symbolism. Tait was awarded the British Columbia Creative Lifetime Achievement Award in Aboriginal Art in 2012, confirming the status of his Indigenous works in an art world that too often ignores them.

Marty Avrett

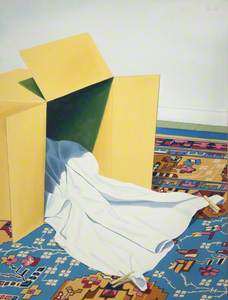

An Oklahoman artist and Professor of Coushatta, Choctaw and Cherokee descent, Marty Avrett's work moves away from the traditional motifs and style found in Indigenous art. Instead, Avrett focuses on representational paintings with an emphasis on form: light, colour and space are accentuated.

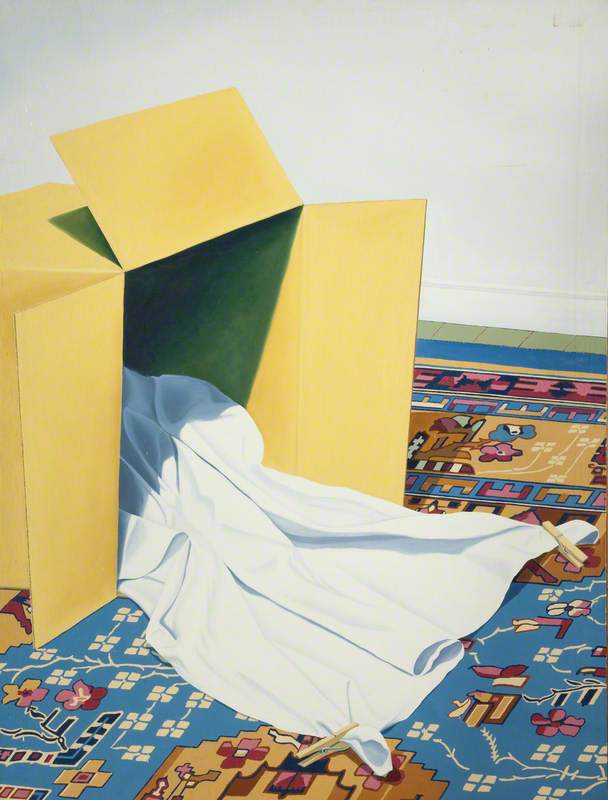

In Sleeping Cloth Fabric, Avrett paints a box on a rug – a piece of white fabric extends onto the floor. The dark shadow inside the box shows a sharp contrast to the yellow, blue and red of the rest of the painting, drawing the audience's eyes inside the box. The folds of the fabric are intricately represented as each shadow creates a sense of softness.

Avrett exhibits great technical skill and painterly craft in his works. Ostensibly less reminiscent of traditional Indigenous art than the other artists mentioned in this piece, it is important nonetheless not to assume that contemporary Indigenous artists should conform to a certain style or subject matter.

These artists and their exquisite works point to the vibrant culture of Native North America and encourage taking a broader view of the contemporary Indigenous art scene. Indigenous people should not be relegated to the past, but allowed to be part of the contemporary conversation. Indigenous artists are not solely a part of history, their creative contributions are felt in the present.

Laura Baliman, freelance writer