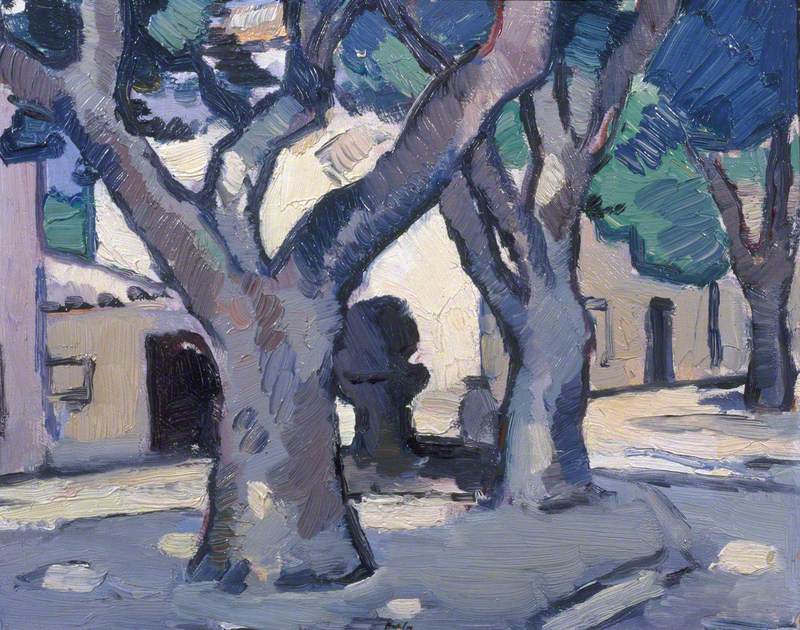

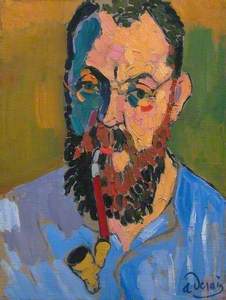

There are far more important paintings made by Henri Matisse in his studio at 19 Quai St Michel in Paris than this small canvas in the Tate collection. Yet this painting tells us so much about the man and his art.

Matisse had two stints in studios in that building, looking one way to Notre-Dame and the other to the Pont St Michel. He'd even lived in a box room in the attic for a brief period before taking up a studio there. But his first meaningful stay was on the fifth floor, from 1894 to 1907 – the difficult early years up to the point where he achieved notoriety as the leader of the Fauves. It was a time mostly beset with anxiety and humiliation: he was dismissed by the art establishment, mocked by the public and shunned by his own family, and endured numerous personal traumas and upheavals.

But when he returned in 1914 to a studio on the floor below, he was among the most famous artists in Paris, and amid one of the most radical and fertile periods of his career, producing his Goldfish and Palette and a sparse, diagrammatic view of Notre-Dame – both now in the Museum of Modern Art, New York – and the Studio, Quai St Michel in the Phillips Collection, Washington DC, among other masterpieces.

The Tate's Notre-Dame, though, is from the middle of Matisse's first spell there. It is a tough, difficult little picture. It captures an artist finding his voice, taking steps away from the dominant language of Impressionism and into something even bolder and rawer, but not yet fully formed. I find its palpable doubt, its unresolved questions – particularly in the chaotic lower part of the picture – tremendously moving.

For Matisse, each painting of Notre-Dame was a reinvention; no two of his responses resemble each other.

The struggle taking place on this canvas was all the more profound because the year before he painted it, Matisse had gone out on a limb to buy Cézanne's Three Bathers from Ambroise Vollard, then about to be the most significant dealer in Paris.

It was a painting he could ill afford. His wife Amélie, who emerges from Hilary Spurling's magisterial biographies of Matisse as a true heroine, pawned a beloved emerald ring to help him acquire it, one of many material and personal sacrifices she would make for her husband's art.

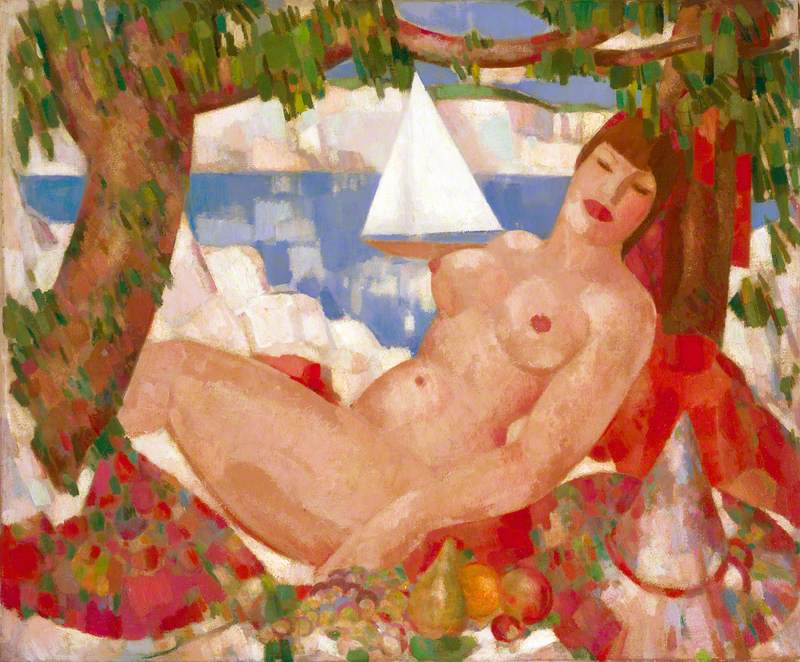

The talismanic significance of the Three Bathers to Matisse cannot be overestimated. He would start each day looking at it, alone, 'by the first rays of the sun rising behind Notre-Dame,' Spurling tells us.

When he finally gave the Cézanne painting to the city of Paris in 1936 – it is in the Petit Palais today – Matisse wrote: 'In the 37 years I have owned this painting, I have come to know it fairly well, though I hope not entirely. It has supported me morally at critical moments in my venture as an artist; I have drawn from it my faith and perseverance.'

The older artist represented the quest for order and balance that Matisse sought for his own art, a classical unity through radical means – reaching back to take a baton from Ingres and even Poussin, while forging a language that entirely modern.

I can't help but think of Matisse wrestling with Cézanne's principles while making this painting.

The upper half of the picture is clear: the hazy morning light on the Île de la Cité, with Notre-Dame's famous towers in shade. But in the lower part of the picture, the space is murkier: the bridge across the Seine dividing the canvas, the smoke billowing from it partly clouding our view of Notre-Dame, barges on the river, and people shuffling along the Quai at the right. Instead of leading us into the picture, the triangle of brown in the bottom corner sits up to picture plane, almost like a gable end.

The painting is also divided chromatically: in the top section, there is a gentle blue infused with white and hints of the pink and green with which Matisse describes the cathedral. But below is a blizzard of colour: turquoise, red, green, blue, yellow, brown, black and white. You have the beginnings of Fauvist boldness here, but Matisse can't yet fully control the colours he is unleashing. It would be another four or five years before his dramatic hues would become luminous.

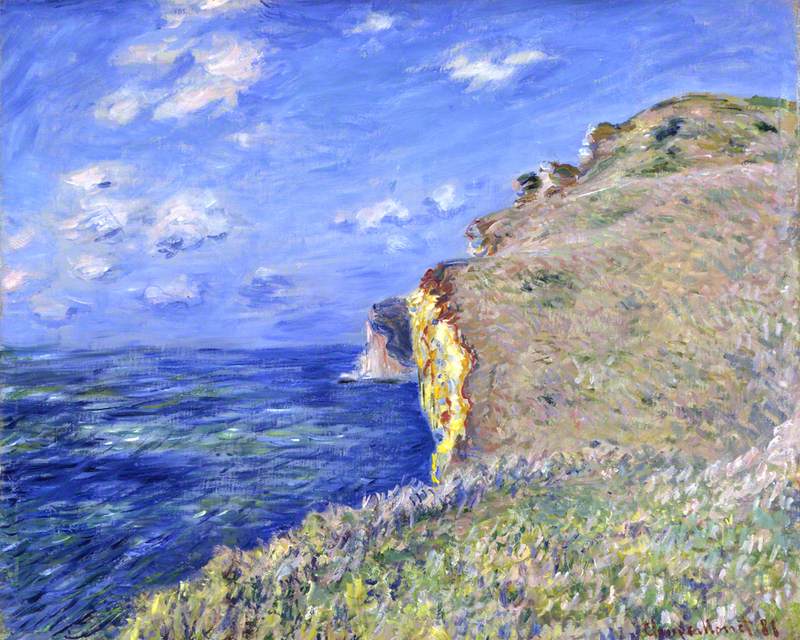

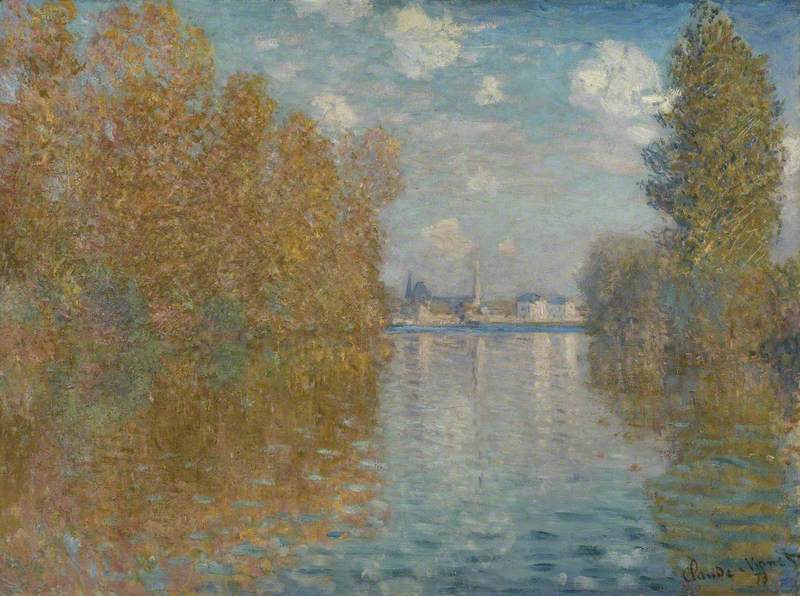

Matisse's paintings of the view of Notre-Dame are not like those other famous cathedral begun a few years earlier, Monet's views of Rouen cathedral. As Simon Schama said in the television series Civilisations, Monet builds 'a symphony of colour harmony' that 'is nothing short of the colour of time', captured at different moments in the day.

Rouen Cathedral: Setting Sun (Symphony in Pink and Grey)

1892–1894

Claude Monet (1840–1926)

For Matisse, each painting of Notre-Dame was a reinvention; no two of his responses resemble each other. 'I never tire of it,' he said of the view in 1919, at the end of his second stint in the building, 'for me it is always new'.

I feel the same about this awkward but always entrancing little work – a painting by a great artist who was not yet great, striving for balance and harmony.

Ben Luke, writer and critic