'That's the man I want!'

In 1944, Henry Marvell Carr shouted these words after a passing sailor at a British naval base in the Mediterranean. Carr was a war artist looking for a new subject to paint and Maurice Alan Easton, a naval telegraphist from Oxfordshire, was the man who had caught his eye.

An Ordinary Telegraphist, Maurice Alan Easton

1944

Henry Marvell Carr (1894–1970)

Chiselled jaw, blue eyes and a muscular physique: Easton was a conventionally handsome young man. Carr depicted him in his square-rig uniform. On his sleeve is his telegraphist's badge – a pair of wings crossed with a lightning bolt. The portrait evokes a traditional ideal of clean-cut masculinity. When the painting was used to promote a naval exhibition in 1946, Easton literally became a 'poster boy' for the Royal Navy.

The Art of Naval Portraiture

Katherine Gazzard (2024)

From admirals and captains to sailors and stokers, the representation of naval personnel has been a significant branch of British art for more than 500 years. The Art of Naval Portraiture charts the evolution of this subject, drawing on the vast collection of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. Some works, such as Easton's portrait, were designed as propaganda for the Royal Navy. Others forged or challenged ideas of gender, heroism and loyalty. Many reveal the personal fears and aspirations of individuals and families caught up in naval affairs.

England began developing its naval strength in the sixteenth century, laying the foundations for a vast maritime empire. In their portraits, some naval officers associated themselves with the nation's growing imperial ambitions, which were bound up with violent and exploitative practices. In 1591, Marcus Gheeraerts the younger painted Sir Francis Drake stood beside a globe.

Sir Francis Drake (1540–1596)

1591

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636)

Drake was a successful privateer. He also participated in transatlantic slave-trading voyages in the 1560s and was later vice-admiral of the English fleet that defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588. The globe in his portrait is turned to show the Atlantic. A small ship flying English colours is shown crossing the ocean, tracing the path of Drake's transatlantic voyages and manifesting England's colonial aspirations in the so-called 'New World'.

In the centuries that followed, naval portraits continued to represent Britain's global connections. In 1748, Joshua Reynolds painted a pair of portraits depicting naval officers Paul Henry Ourry and George Edgcumbe. The former was shown with a young Black servant, known as 'Jersey'. This boy is a reminder of the human cargo brought to European shores via Atlantic trade routes in this period. Part of the Royal Navy's role was ensuring the security of British traders using these routes.

Admiral Paul Henry Ourry (1719–1783), MP, with 'Jersey'

c.1748

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Edgcumbe, meanwhile, was pictured on his Cornish country estate with his ship in the background and a long-tailed paradise whydah bird perched above his head. The bird, like Ourry's servant, came from Africa.

Captain the Honourable George Edgcumbe (1720–1795)

1748

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

These two paintings were made for display in the Mayoralty House at Plympton in Devon, which was only a few miles away from the naval dockyard at Plymouth. Both Edgcumbe and Ourry were involved in local politics. Their portraits trumpeted the Royal Navy's role in connecting Plymouth to a vast network of global trade, wealth and exploitation.

Many early naval officers combined seafaring with other activities, such as scholarship, politics and commerce. In around 1620, Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, was painted by Daniel Mytens wearing the elaborate vestments of the Order of the Garter, while a window behind him showed a view of the sea.

Charles Howard (1536–1624), 1st Earl of Nottingham

c.1620

Daniel Mytens (c.1590–1647)

Originally, the background depicted Howard's fleet defeating the Spanish Armada in 1588, but now only traces of sails and masts remain visible. The combination of ceremonial dress and a naval scene highlighted Howard's dual role as courtier and seafarer.

After Charles II took the throne in 1660, the Royal Navy underwent a process of professionalisation. Naval administrator (and famous diarist) Samuel Pepys reformed the training, payment and promotion of officers. This gave rise to a sense of shared professional identity, which was reflected in portraiture. Officers were increasingly shown in coastal settings with pieces of nautical paraphernalia, such as anchors and telescopes.

Resting his hand on a cannon, Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, typifies this trend in his portrait by Peter Lely from 1666.

Flagmen of Lowestoft: Edward Montagu (1625–1672), 1st Earl of Sandwich

c.1666

Peter Lely (1618–1680)

Another important development came in April 1748, when the Royal Navy introduced its first official uniform, consisting of blue coats with gold lace decoration. As a visual manifestation of the wearer's rank, uniform quickly became a defining feature of naval portraiture.

An early example is Thomas Hudson's portrait of Vice-Admiral John Byng, painted in 1749. Byng is shown in full dress uniform, which was designed for ceremonial occasions. The gold tassels indicate his rank. A plainer uniform, known as undress, was used for everyday wear.

Admiral John Byng (1704–57), Admiral of the Blue

1749

Thomas Hudson (1701–1779)

At first, uniform was only for officers, being intended to reinforce their authority at sea and their social status ashore. It was more than a century before common sailors were granted uniform.

Commissioning a portrait was expensive. In practice, this meant that wealthy senior officers had their portraits painted far more often than those under their command. Produced in 1832, John Burnet's sensitive study of retired boatswain William Mathews is a rare exception to the rule.

William Mathews, a Greenwich Pensioner, c.1832

1832

John Burnet (1784–1868)

Mathews was a pensioner at Greenwich Hospital, which provided support and accommodation for naval veterans. Greenwich Pensioners were stereotyped as rowdy, drunken, and lascivious, but Burnet's portrait is a more sympathetic image.

Naval service was often understood in relation to masculine stereotypes, especially those involving heroism and command. While some portraits directly associated naval warfare with masculine virility via the phallic symbolism of swords and cannons, others presented different ideas of masculinity.

Appearing in a double portrait with his son and pet dog in 1775, Captain John Bentinck was represented as a devoted father.

Captain John Bentinck (1737–1775), and His Son, William Bentinck (1764–1813)

1775

Mason Chamberlin the elder (1722–1787)

Women sometimes feature in depictions of naval families. In Richard Livesay's group portrait of the Grindall family from around 1800, Katherine Grindall is depicted alongside her naval officer husband and their four sons. One of the boys is dressed in midshipmen's uniform, indicating that he too has joined the Royal Navy.

Captain Richard Grindall (1750–1820) and Katherine Grindall (1759–1831) with Their Sons

c.1800

Richard Livesay (1750–1826)

Katherine is positioned at the heart of the family unit, pulling the group together for a brief shared moment. The portrait highlights the emotional labour of naval wives, who maintained the family's affairs while their relatives went away on long and dangerous voyages.

Women were also an important part of the audience for naval portraiture. After John Robert Wildman's portrait of naval officer and polar explorer James Clark Ross was exhibited at the Society of Artists in 1834, The Lady's Magazine called for him to be 'made a pet lion of by the ladies'. Sexual attraction to naval men was encouraged by the press as a legitimate expression of feminine patriotism.

Commander James Clark Ross (1800–1862)

1834

John Robert Wildman (1788–1843)

The Women's Royal Naval Service, also known as the Wrens, was established in 1917, enabling women to undertake official naval roles for the first time. Dissolved in 1919, the Wrens reformed at the outbreak of the Second World War and merged with the Royal Navy in 1993. The Wrens were known for their stylish uniforms. To quote the title of Christian Lamb's memoir about serving in the Wrens, 'I only joined for the hat.'

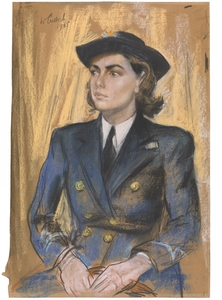

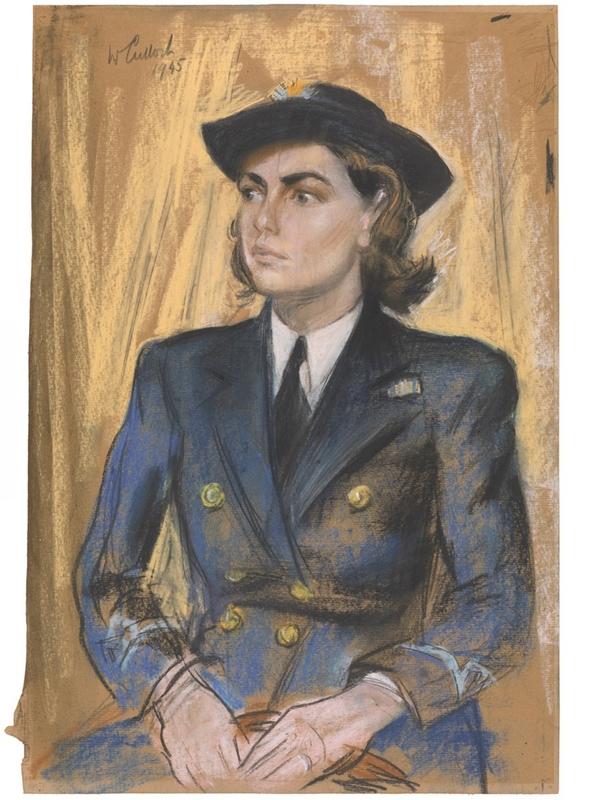

In 1945, Joseph McCulloch rapidly sketched the likeness of a Wren officer in pastels. He emphasised her high cheekbones, arched eyebrows and wide eyes, echoing the striking looks associated with the era's female movie stars and evoking the glamorous reputation of the Wrens.

Portrait of a Wren Officer

1945

Joseph Ridley Radcliffe McCulloch (1893–1961)

The prominence of the Royal Navy in British public life declined in the second half of the twentieth century. This period witnessed the dissolution of the British Empire and a reshaping of global economic, political and technological power structures.

One of the most recent naval portraits in the collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, is John Wonnacott's Admiral of the Fleet Terence Thornton Lewin. It was painted between 1995 and 1998 to commemorate Lewin's retirement as Chairman of the Museum's Trustees. The self-absorption implied in the pun 'naval gazing' might seem fitting when applied to the painting.

The setting for the portrait is the Painted Hall of the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich. Stretching out above Lewin's head are eighteenth-century murals celebrating royal power and maritime success. Yet Lewin's toe pokes beyond the bottom edge of the picture. This creates an open-ended quality, inviting future generations to continue engaging with naval history and its associated art.

Naval portraits have much to tell us about power, identity, empire, gender and memory. They are records of events, individuals and stories that have shaped the world in which we live today.

Dr Katherine Gazzard, Curator of Art at Royal Museums Greenwich and author of The Art of Naval Portraiture