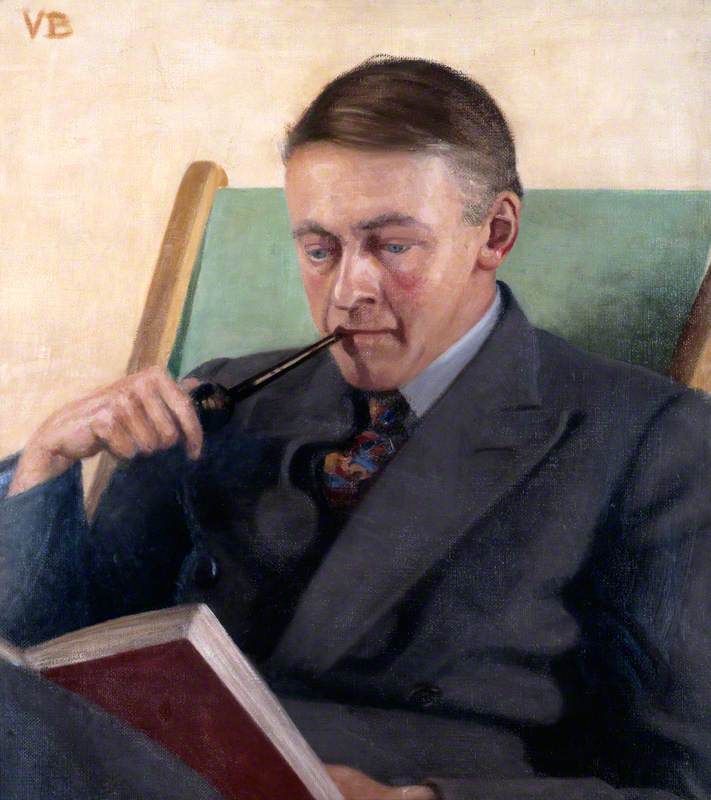

Between the wars she was Britain's most beguiling pianist with a collection of pictures almost as impressive as her list of possible lovers, said to include, among others, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Ramsay MacDonald and D. H. Lawrence.

And yet Harriet Cohen's most enduring love affair, with the married composer Sir Arnold Bax, was tinged with sadness and betrayal. When, after a liaison of more than three decades, his wife died, Bax not only refuse to marry her but revealed he had had a second mistress for the preceding twenty years.

Soon afterwards the pianist cut her right hand in what was described as an accident and her musical career never fully recovered.

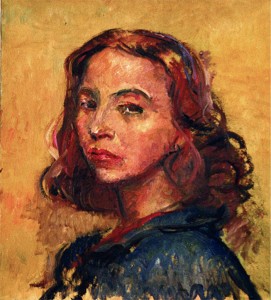

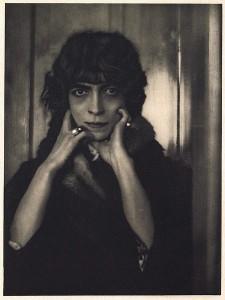

Although barely remembered today, in her prime Harriet Cohen was a mesmerising performer. The 'naked civil servant', Quentin Crisp, described how, with her 'beautiful Byzantine looks' she would wait until the audience was on the cusp of restlessness before sweeping on to the stage. Then, she would bow solemnly, first to the conductor, then to the audience. As she sat down her dress – 'never flashy but always extremely visible' – would spread out voluminously behind her.

After carefully removing jewellery from her hands, she would finally give the conductor a nod and play the first note. By then, said Crisp, it did not matter what she played, everyone was already enraptured. Composers fell over themselves to dedicate works to her and she had a wide circle of friends from other areas of life including politics, dance, literature and art.

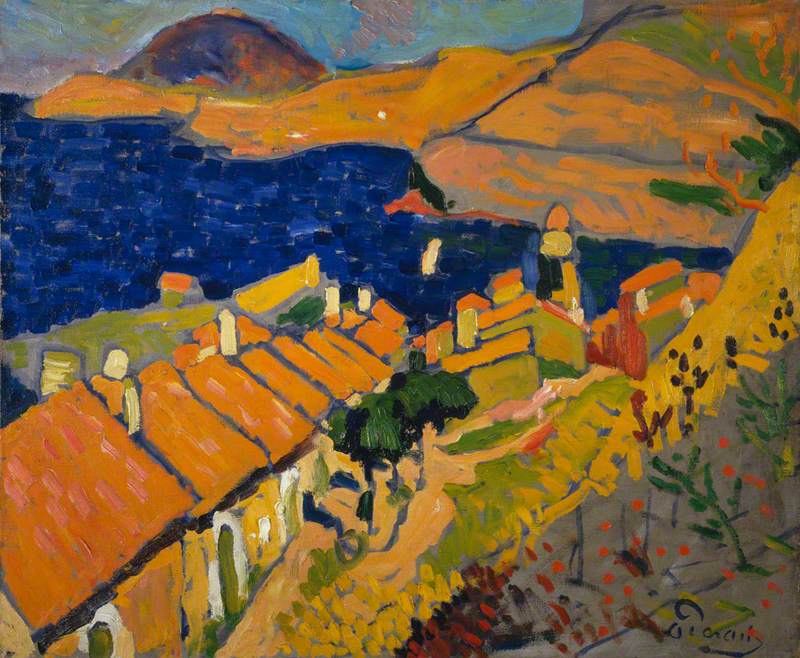

A still life by André Derain was one of many fine pictures in her London home – a house and a later flat were both paid for by the wealthy Bax.

She mixed with Matisse, Picasso and Modigliani and made special mention of Derain in her memoirs A Bundle of Time. 'He was very tall and one often thought of him as the soldier he had been... the eternally beautiful flower painting hanging in my studio daily reminds me of him.'

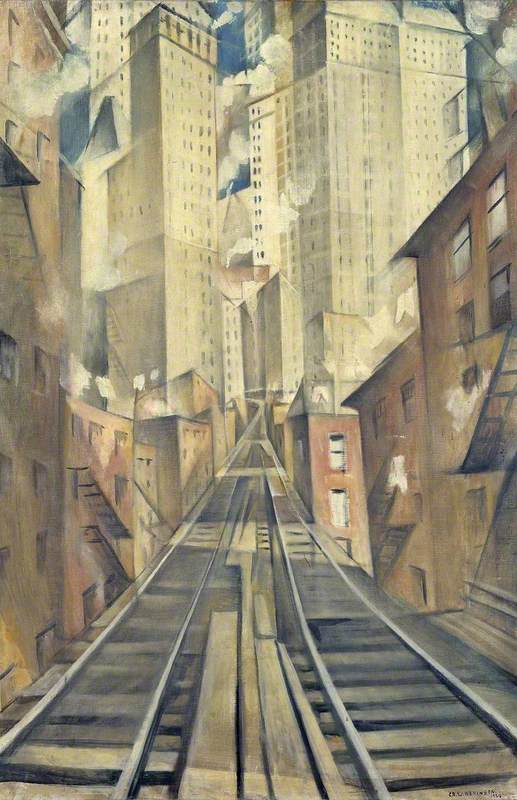

She was also close to many British artists including C. R. W. Nevinson and his wife Kathleen. They gave her a painting of a French interior in a snowstorm 'which made the starting point of my collection.'

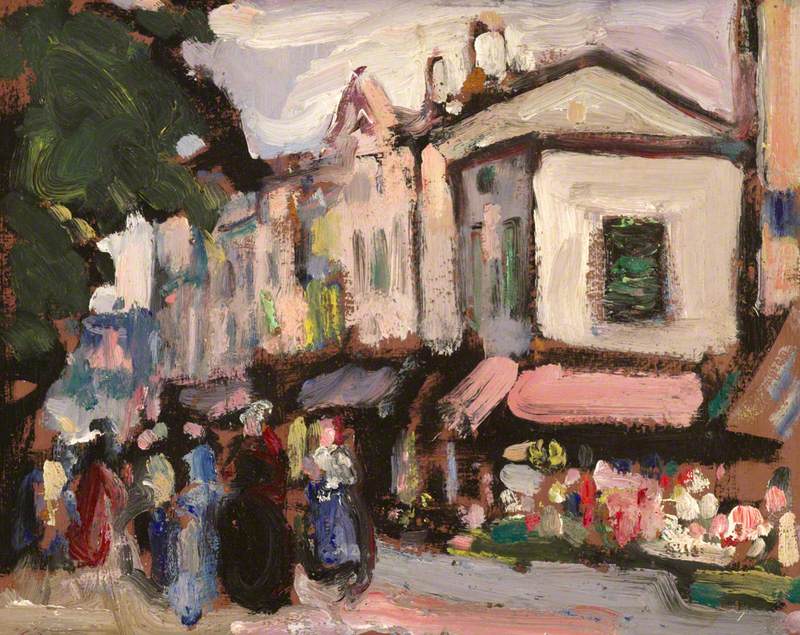

A Paris street scene by J. D. Fergusson, the partner of another great friend, the dancer Margaret Morris, was also among her most treasured possessions.

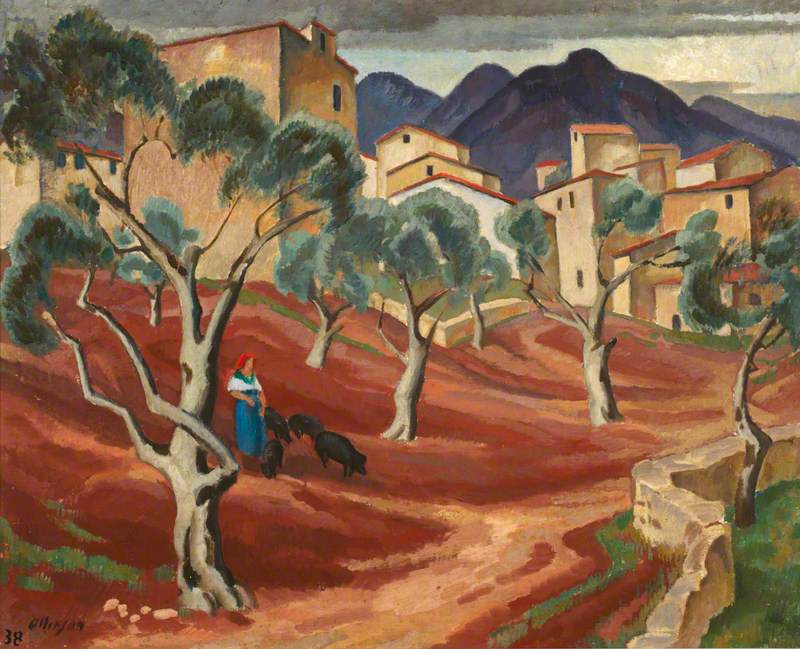

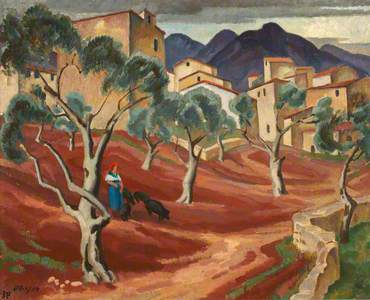

Her friendship with another dancer, the Russian ballerina Tamara Karsavina, led to a meeting with Adrian Allinson who had painted Karsavina's portrait. She later acquired his Village in the Midi.

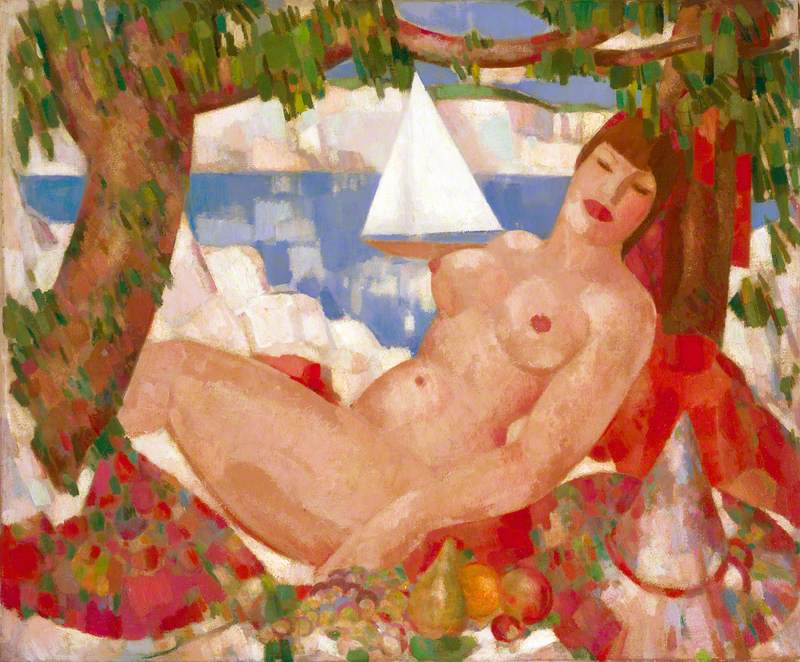

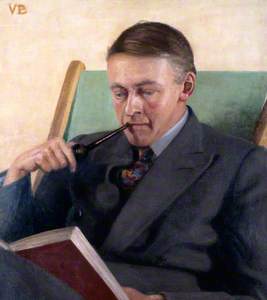

Duncan Grant, who studied at the Slade with both Nevinson and Allinson, features twice in the Cohen collection with a floral watercolour and an oil of Cuckmere Haven, not far from Grant's and Vanessa Bell's home at Charleston in East Sussex.

Harriet Cohen also encouraged struggling artists, in particular Harold and Gertrude Harvey, 'a very pleasant couple, happy in their mutual trade of painting but oh, so obviously, so desperately poor.'

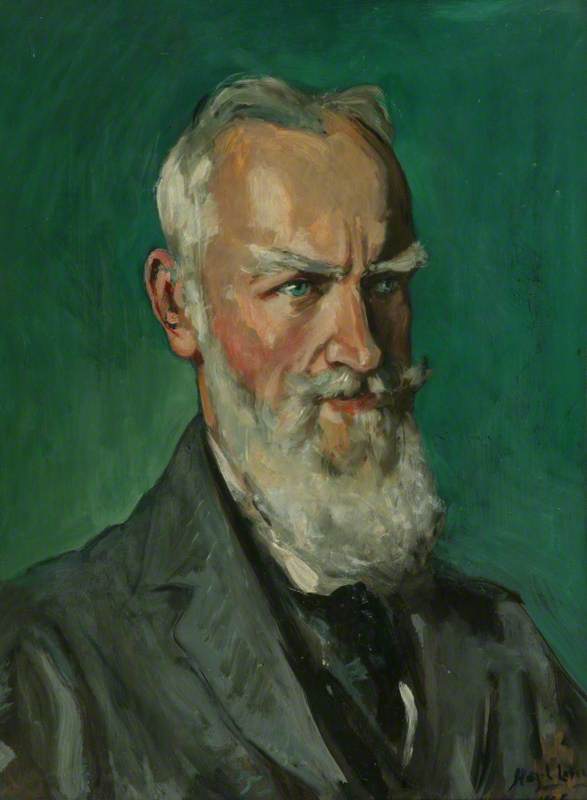

Harriet, with help from George Bernard Shaw (yet another of her admirers), decided, in 1929, to stage an exhibition of Gertrude's flower paintings at her home. She called it the 'Woolworth Exhibition of Pictures' as all the paintings were priced affordably at £5.

In her autobiography, some 40 years later, she said the show 'practically wrecked my home... and lost me hours of practice, however, at this far distance of time I still say I'd do it again.'

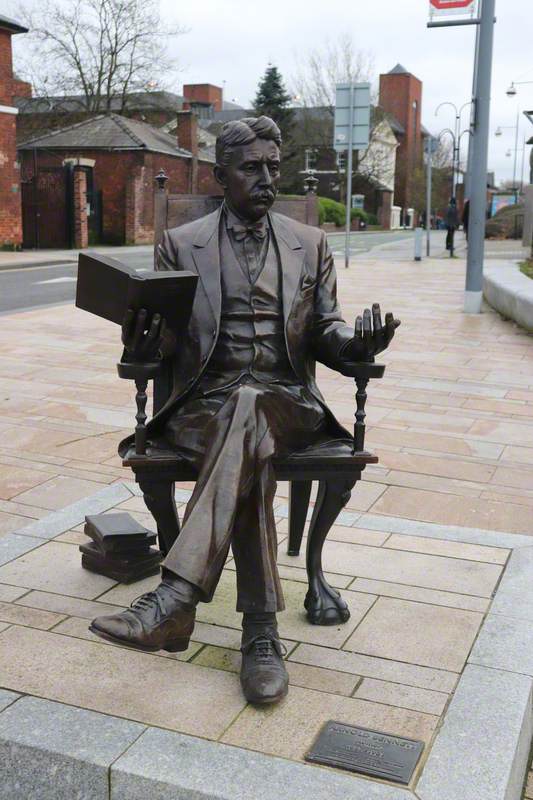

Harriet Cohen's generous spirit is also reflected in her promotion of contemporary British composers. John Ireland, William Walton and Edward Elgar all dedicated works to her and she premiered compositions by Vaughan Williams, Manuel de Falla and Arnold Bax.

As this YouTube audio clip shows, despite tiny hands which couldn't stretch an octave, she was also renowned for her interpretation of Bach.

Overcoming repeated bouts of ill health, including TB, she toured Europe and North America with several romantic encounters along the way. In Venice, for example, she met the writer, painter and political activist Carlo Levi who had recently published a bestseller (also a film) called Cristo si è fermato a Eboli (Christ Stopped at Eboli).

By chance Carlo Levi was staying at the same hotel as Harriet. She had a translation of his book in her bag and asked a porter to procure a signature while she made for the beach: 'It was very, very hot and I was in and out of the sea all morning or sitting under the awning of my cabin trying to dry my long hair... "allow me to help you" said a voice behind me... and there stood my author. He took a towel and worked at my hair, promising to autograph Cristo.'

Alongside the eventual inscription – 'to Harriet whom I have known for six thousand years' – he drew an owl which, with his beak-like nose, he apparently resembled. A more finished work ended up in her collection.

After the war her performances lost some of their lustre. The injury to her right hand became increasingly restrictive prompting Arnold Bax to write a piece for the left hand only. When the composer died in 1953 much of his estate was divided between Harriet and his other mistress Mary Gleaves.

One of the last pictures she acquired was Storm Clouds by John Napper which dates from 1966, a year before her own death. The artist was a great friend of Arnold Bax and perhaps the image made her think of their often tempestuous affair which nevertheless endured for some 40 years.

In a biography, Music and Men, Helen Fry charts their relationship through a correspondence of 1,850 letters which Harriet Cohen stipulated should be kept locked away for thirty years. In all, she left four trunks of 3,000 letters. One trunk, which contained 600 letters, was reserved for other 'great loves and adorers'.

While her recordings are her most lasting legacy, her picture collection, housed at the Royal Academy of Music where her career began, speaks of a rich and varied life. She had both magic in her hands and a keen collector's eye.

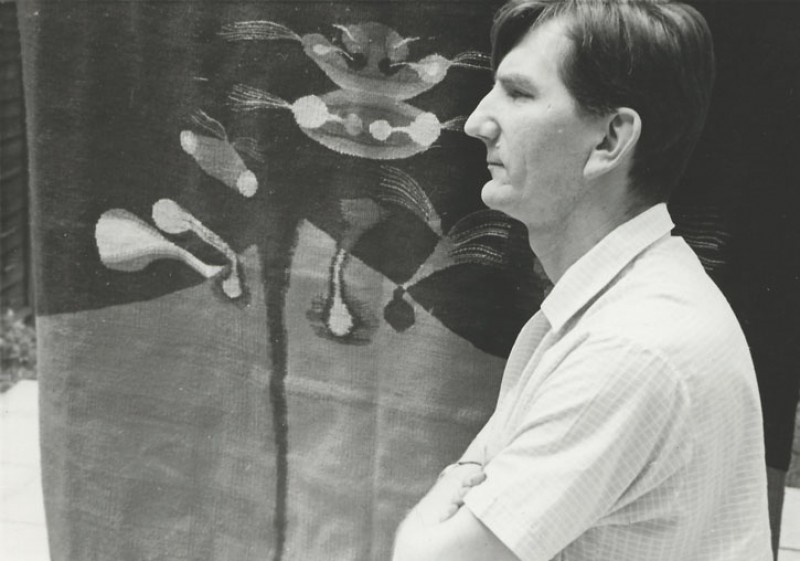

In all, Harriet Cohen left more than 40 pictures to the RAM including works by Marc Chagall (1887–1955), Aristide Maillol (1861–1944), Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947), Matthew Smith (1879–1959), William Scott (1913–1989), Josef Herman (1911–2000), Edward Wolfe (1897–1982) and Marie Laurencin (1883–1956) – some of which are at the top of this piece.

James Trollope, author and columnist