When I teach undergraduates at King's College London, I take them to The National Gallery with my colleague Robin Griffith-Jones, who is both a biblical scholar and art historian. While we're there, we invite them to reflect on what a 'theological hang' of the collection might look like, as distinct from the more typical arrangement of pictures by school, region, or historical period.

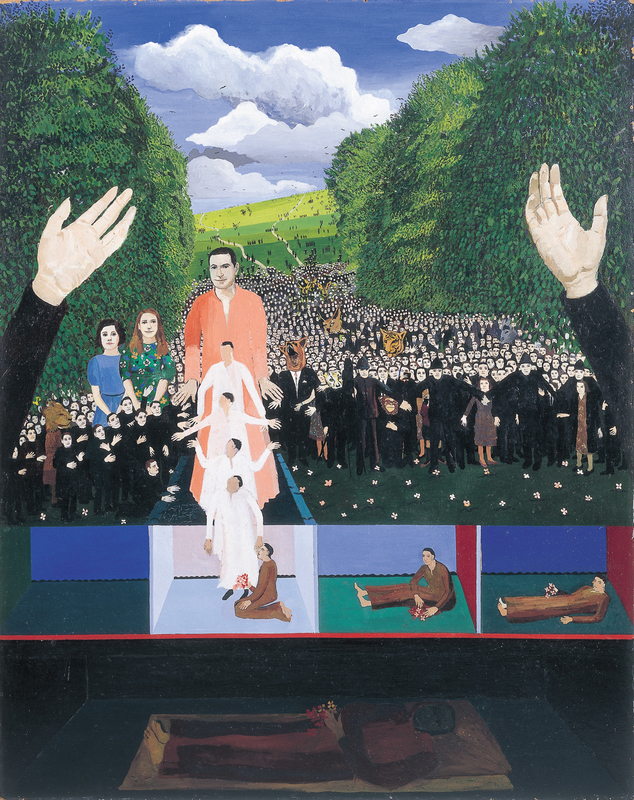

This is a 'theological hang' of sorts. It is structured around three pairings of artworks, with one final work to cap things off: seven works in all. My selections all come from the Methodist Modern Art Collection, whose consistent quality makes any selection of some over others very hard. The thread that binds my choices is a focus on the hands of Jesus Christ, which are movingly prominent throughout the collection (as in this painting by Euryl Stevens).

Hands have always played a special role in visual art, partly because they are proof of an artist's mettle. They are one of the most complexly expressive parts of the body, and some of the hardest to draw, paint, or sculpt, which is why, historically, they invariably remained the responsibility of the lead artist in a workshop even while other sections of a commission were devolved to a team of assistants.

Hands are among the most creative parts of the human body. Jesus's hands are no exception. The hands of Jesus touch, work, embrace, heal, bless, share food. Then they are nailed to a cross.

For Christians, the killing of Christ's hands – a nail driven into the heart of each of them in turn – does not kill the divinity in work in them: the divinity that made Adam and that raised Lazarus. These hands, even in death, are still making a new world.

Epiphany by Albert Herber

Albert Herbert shows us the infant Jesus lying next to his mother (maternity was one of the artist's abiding themes). His face is turned towards us and his mother's is turned towards him. We cannot see his hands; they are swaddled. We might say that their 'hour has not yet come' (John 2:4). Mary's hands must, for now, be active on her child's behalf, until his own hands are ready.

The swaddling of Jesus is of a piece with Mary's love: it enwraps him reassuringly. He is in a secure cocoon of light and maternal closeness in the tiny, holy house.

Yet, even in this security and warm light, there is a sarcophagus-like quality to the crib. And we know, if we know the story, that one of the approaching Magi is carrying a gift of myrrh, for the anointing of dead bodies. The presentation of this gift will itself be an epiphany, or 'showing', and of a darker kind.

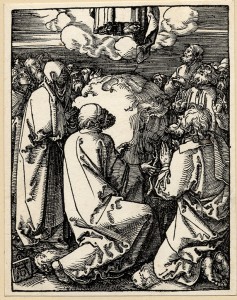

The Deposition by Graham Vivian Sutherland

Christ's emaciated body is slung like a hammock – a shape echoed in the linen strips above him and the linen sheet below. The position of the body has led to comparisons with other works of Western art from which Sutherland perhaps drew inspiration: Hans Holbein the younger's Passion of Christ altarpiece, Raphael's Borghese Entombment and Robert Campin's Seilern Triptych. Myself, I think of Caravaggio's Deposition of c.1600–1604, now in the Vatican. It has the same loose swag of linen beneath the body.

Deposition

c.1600–1604, oil on canvas by Caravaggio (1571–1610)

As in Sutherland's composition, the slung body of Christ in Caravaggio's work is being lowered towards the impenetrable darkness of a waiting tomb. But Caravaggio gives great prominence to Christ's heavy, muscular arm, dropping vertically, radiant in the crosslight, its index and middle fingers seeming to point at the stone of his tomb as though prophetically ('the stone that the builders rejected has become the chief cornerstone' – Matthew 21:42). By contrast, the arms and hands in Sutherland's work have dissipated into abstraction. It is as though not even a memory of creative agency remains.

Caravaggio's Christ – though dead – seems to indicate something more to come. Sutherland doesn't let us have that reassurance.

The Pool of Bethesda by Edward Burra

... The Pool of Bethesda by Edward Burra

— Hereford Cathedral (@HFDCathedral) March 22, 2013

... pic.twitter.com/h9XoWAqBUg

Though it depicts a miracle from Jesus's earthly ministry, there is something here of a Harrowing of Hell. Maybe that is appropriate, inasmuch as the opening of a way beyond sin and death is itself a momentous act of world-healing.

With the sole exception of Jesus, the faces of all those in this dark realm – the sick and immobile as well as their 'helpers' – seem only half-formed. It is as though (to echo C. S. Lewis's Till We Have Faces) they still await a moment when their true faces will emerge, perfected, glorified, fully individual.

The human 'helpers' are part of a competitive economy: a rush to access (before anyone else can) the healing benefits of the pool when its waters stir, a race for the exit from this hell. This is why the man who is the focus of Jesus's attention has been trapped there for 38 years (John 5:5). He cannot compete.

Jesus's hands – open to us almost as much as to the infirm man – are the most generous element of the composition. Jesus has no need of the pool. In him, a new economy is at work.

The infirm man's hands express… what? Astonishment, disbelief, acquiescence, joy? We can't see his face, and only have his hands to go on, so we must use our imaginations.

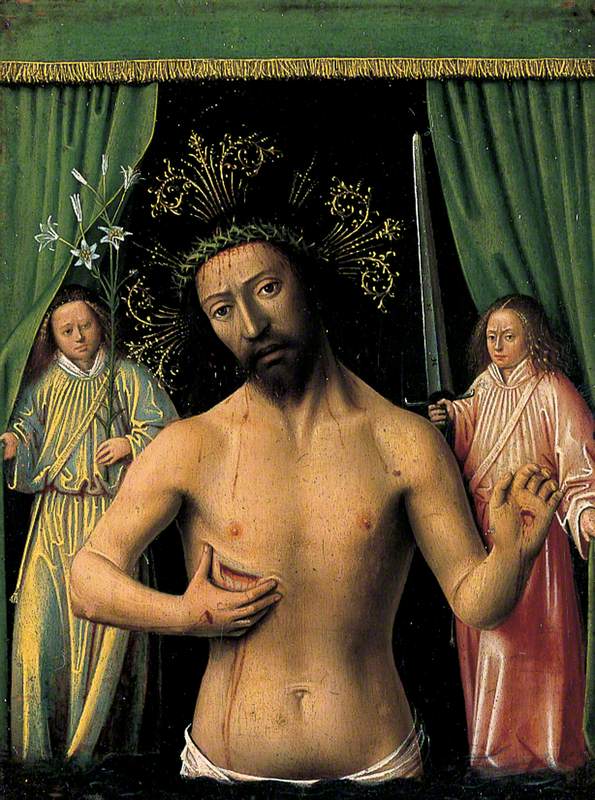

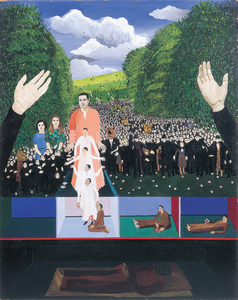

Behold the Man by Norman Adams

What should one make of the brightly coloured, curved 'bars' in the left- and right-hand corners of the lozenge shape from which the face of Christ regards us? Are they ripples of spiritual energy, or abstract decorative additions to a more figurative central motif?

I have seen other great 'heads' painted by Adams – including Saint Paul's on the road to Damascus, clutching his head with long, tubular digits – which suggest to me that the curved bars of colour in this work are actually fingers. At the moment when he is presented to the hostile crowds by Pilate, crowned with thorns (John 19:5), Adams shows Christ with hands raised.

Are they raised in self-protection, as Saint Paul's hands will later be raised to shield him from the assaulting light? Perhaps. But maybe they are being raised in prayer (as in the classic orans position), or even in blessing.

Adams liked to paint lozenges in the place of thorns, because (as primitive leaf forms) they indicated the thorns' future transformation – their return to an innocent state before their evolution into weapons. In Adams's depiction of the raised hands of Christ, we may find a visual echo of Burra's raised hands of Christ in The Pool of Bethesda, and be reminded that this suffering man is – even in extremity – working to restore innocence and accomplish our healing.

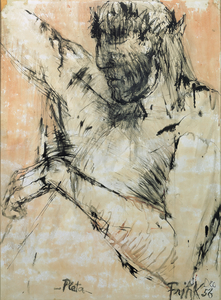

Pietà by Elisabeth Frink

This is a moving reprise of the Man of Sorrows, or imago pietatis, image-type – once one of the most popular devotional images in Europe. In its most typical form, it shows a half-length Christ, head tilted to one side, and arms (the hands bearing the marks of the nails) folded across his chest.

The undecidability of just which moment in the narrative of Christ's Passion Frink's pen and watercolour drawing depicts (is it a Deposition? Is it a Pietà?) is very much a feature of the imago pietatis tradition as well. There too, the precise point in the story is unclear. It is better to think of such images as compressions of the whole: distillations.

What Frink accomplishes in her contribution to this tradition is a most extraordinary, and intensely poignant, naturalism. There is nothing stylised or formulaic here. The limbs have become untidy. There is a helplessness to Christ's left arm, accentuated by his cocked wrist and curling fingers (a possible echo of Matthias Grünewald's Lamentation at Aschaffenburg in Germany). He reminds me of a vulnerable elderly person in a hospice bed, in the process of being turned and repositioned to prevent bedsores.

The right arm leaves us an ambiguity to wrestle with. Where might that arm take us if we could follow it with our eyes? What lies at the end of it?

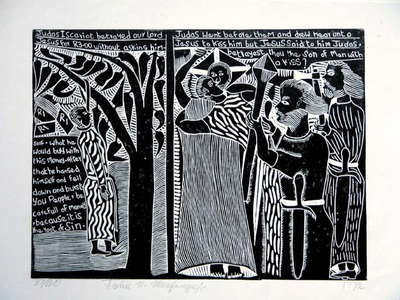

Judas Iscariot Betrayed Our Lord Jesus by John Muafangejo

Judas Iscariot Betrayed Our Lord Jesus

(edition 37/100) 1972

John Muafangejo (1943–1987)

Judas's arms are flung around Jesus in what almost seems like passion, and there is nothing decorous about his full-frontal kiss. But in this extravagant act, Judas nevertheless 'keeps his hand hidden' (both hands, indeed, are out of sight to us, the viewer). He is dissimulating.

Meanwhile, the soldiers' hands are occupied with the tools of malevolence.

Judas's body is dramatically unbalanced as he leans and twists to achieve his desired position. In this, he contrasts sharply with Jesus's solidly planted, secure, vertical axis. And there is a further contrast in that Jesus, by contrast with Judas, 'shows his hand'. His right hand asserts his ability to transcend the murky and violent dynamics of this 'hand off' ('betray' in New Testament Greek is 'paradidōmi', which literally means 'hand over'). With it, he gestures to a higher and more radiant purpose.

In this, Muafangejo's work gives us one possible way in which we might read the raised right arm of Frink's dead Christ in her Pietà: as a gesture to some sort of transcendence, a hope that is not yet seen.

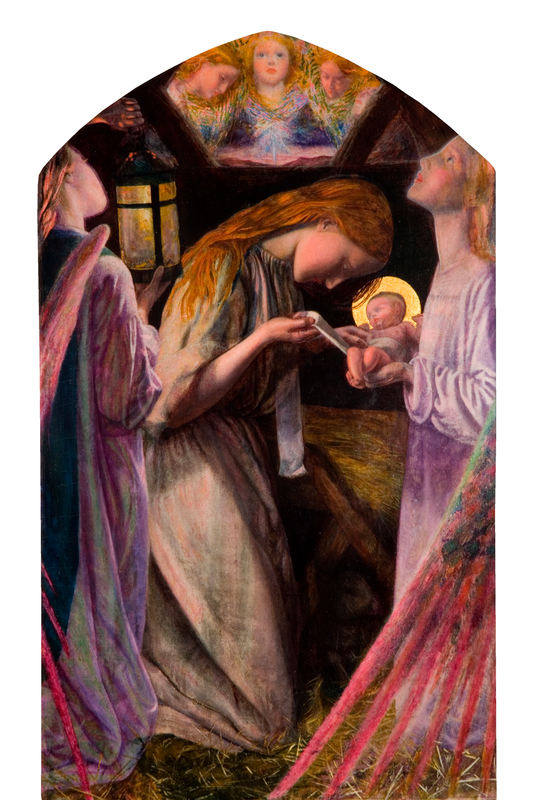

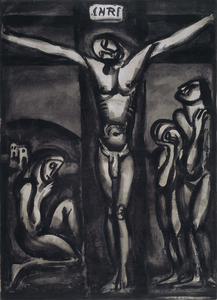

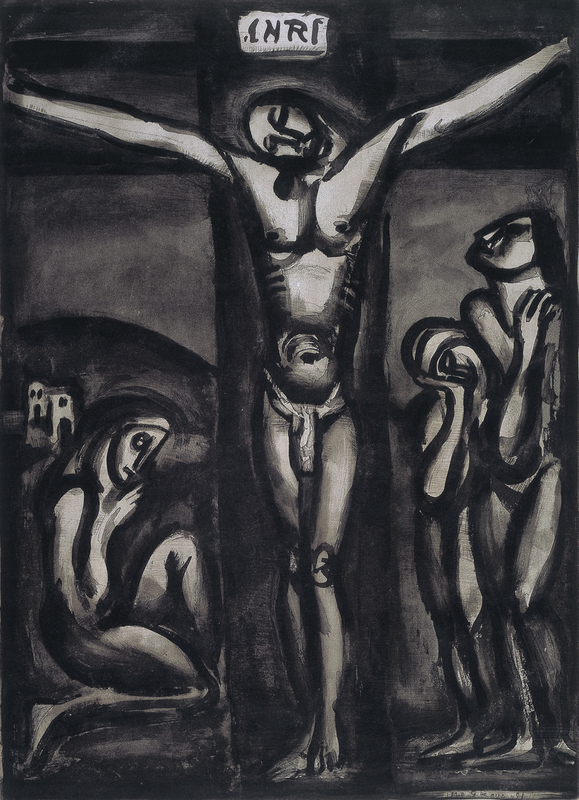

Aimez-vous les uns les autres? (Love one another) by Georges Rouault

Aimez-vous les uns les autres? (Love one another)

(from 'Miserere') 1923

Georges Rouault (1871–1958)

Once again, and for a final time in this curated group of images, we are alerted to think about Christ's hands through their striking omission. Once swaddled, then alive and supple and creative, then limp and immobilised: what (in their extension beyond our sight) are they doing here?

Though this is a crucifixion scene, there is a serenity to Rouault's Christ. As the theologian Alison Milbank has suggested:

'[This serenity] reaches back beyond the suffering humanity to the divine unchangeableness, and this stability is revealed, paradoxically, in the place of pain. Thus, in the face of Christ, we know and see the Father.'

This Jesus invites our calm contemplation: offering himself to us as a priest or minister offers the sacrament. In his sacrifice of himself, he prays for us. And in those long arms, which extend beyond the very edge of the engraving (just as the cross runs out of the picture both above and at each side) we may discern that this prayer has nothing less than a cosmic reach.

The hands of Christ are re-making the world even from the cross. Those who look at the cross and know what they are seeing are the first citizens of this new creation, and can begin its work by lending their own hands to it.

Professor Ben Quash, Chair in Christianity and the Arts at King's College London