As in Aby Warburg's Mnemosyne Atlas, our mind is impregnated by the memories we collect. Those images we consume – photos we see, paintings we like, places we have been – eventually may become useful in the research of art. And that is why sharing art collections online may be the new art historical tool.

The same way a random face may ring bells in our memory, a painting can also trigger the impression that we may know it, or a part of it, from somewhere. This collection of images we carry in our memory is often a personal experience that cannot be transferred to another person: you could end up discovering a particular detail which your colleague or neighbour would not, and vice versa.

I have identified the style of Gustav Pope, but it was largely by an unrelated chance that I also happened to recognise the four sitters, as well as the very place in which they were depicted.

Ever since public collections began to be shared online, many anonymous artworks have been happily identified by visitors. This phenomenon may be useful for important paintings by famous artists, but also for those pictures whose author has been lost to us; either because signatures were not styled, worn off, or because inscriptions and documents were, in time, separated from the piece. By chance, readers can recognise the style of a particular artist, the identity of a sitter, or the place and time a photo or painting was executed.

Art UK has recognised the potential of this unattached and voluntary taskforce and has encouraged the public to a collaborative exchange through their initiative Art Detective. Connoisseurship is still a valuable method of investigation, but it often fails to identify works by artists that are not properly catalogued, or who are not well established in art literature. Of that kind, Victorian art has many examples.

Researching the Victorian painter Gustav Pope has been hard work: his oeuvre has been dispersed without much documentation, and his life was mostly forgotten when Victorian art became underappreciated during the first half of the nineteenth century. For the combination of high-quality work and a relatively unknown name, it also has been particularly vulnerable to unethical dealership practices during that time: signatures were removed, or added, to give the impression that the work is by a more famous artist. One of such cases, Daughters of King Lear – a magnificent painting in the Ponce Art Museum, Puerto Rico – entered the collection as a work by Rossetti. Later, it was correctly identified as an autograph work by Pope.

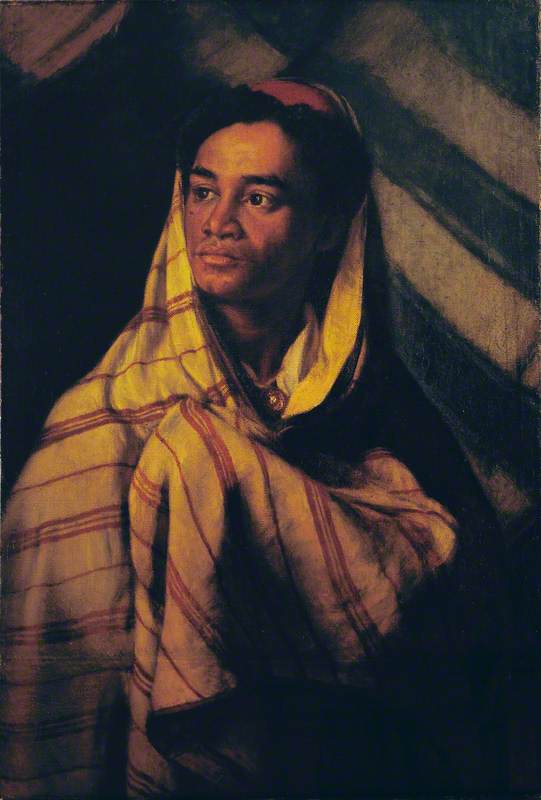

A diligent pursue of documents, mentions and images is of utmost importance. I also have crossed paths with felicitous occurrences of identification: the case of an oil painting from the York Castle Museum, which was catalogued as Interior with Figures, 1863, by an unknown artist. In this canvas, I identified the style of Gustav Pope, but it was largely by an unrelated chance that I also happened to recognise the four sitters, as well as the very place in which they were depicted. I had seen those faces, attitudes, and manners before while browsing thousands of photographs from the Royal Collection with the objective of learning about Victorian fashion and mourning customs.

The making of The Music Room

The painting shows a lavish music room and a group that resulted in being completely out of the ordinary. The sitters are three of Queen Victoria's daughters: Beatriz, Alice, and Louise; they keep company to Louis, the Duke of Hesse, Alice's fiancé. The ambience of the room is that of pleasant idleness, which makes the scene more intriguing. It is not at all like the typical, stern portraits of the royal family, with their strict etiquette and carefully planned appearance. The painter may have been adapting the spirit of a snapshot to this portrait, as a record of a single moment in time, or perhaps he was competing directly with the photographic medium in timing and subject matter.

The advent of photographic portraiture took many clients away from portrait painters, especially those clients in the upper classes who had better access to the new technology.

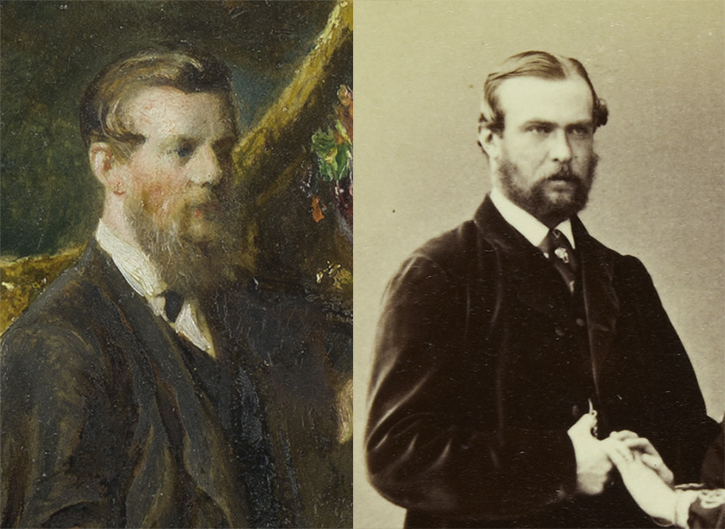

'Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse' (left) and 'Princess Alice with Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse' (right)

(details), both 1863, albumen print (left) and hand-coloured albumen carte-de-visite (right) by John Jabez Edwin Mayall (1813–1901)

Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children were among the first and most assiduous users of photography during the mid-nineteenth century, but they embraced the novelty while retaining the services of traditional painters like Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Edwin Landseer, Francis Grant, and James Sant. Portraits by these painters were usually dignified and pompous. The Music Room presents instead a relaxed afternoon gathering.

It also exhibits a loose brushstroke and luminous palette, executed with an impressionistic technique. This is remarkable since, up to that date, the freedom of Impressionism had not yet developed as a movement. A spontaneous execution like this could have been deemed careless by critics. This shows how Pope's skills were fiercely rivalling the accuracy and instantaneity of the photograph, the preferred medium of the new generation of royals.

The party in The Music Room

This group portrait was painted amid an unofficial and casual setting, in which Princess Louise, the future Duchess of Argyll, plays the piano, and her audience is formed by her sisters Beatriz and Alice, and the Duke of Hesse. The Duke sports what seems to have been his signature pose, standing in contrapposto with a leg crossed over the ankles. Beatriz, the little girl seated on the floor, is an almost exact likeness to her photographs at that age, and her eyes and hairstyle are unmistakable. Princess Louise's profile and wardrobe can be also traced back into familiar photographs, and her piano-playing skills are well documented. The similarity in faces, attitude, and ages of the models as a group makes almost certain their identity.

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine' (right)

(detail), 1865, albumen print by Hills & Saunders (active since 1852)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'Princess Louise, Marchioness of Lorne' (right)

(detail), 1871, albumen print by Sergey Levitsky (1819–1898)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'Princess Alice, Duchess of Hesse and by Rhine' (right)

(detail), 1861, albumen print by John Jabez Edwin Mayall (1813–1901)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and Princess Beatrice (right)

from 'The royal children in mourning' (detail), 1862, photograph by William Bambridge (1819–1879)

An inscription on the back of the painting, of which an image was kindly provided by the York Museums Trust, cites the year of the painting as 1863. Upon comparison with a timeline of events within the royal family, the dating could be reconsidered. Instead, it may reflect the year of acquisition by its first owner. The picture could have been started at the end of 1861 when Alice and Louis were engaged but not yet married. The royal princesses are shown dressed in vivid colours, an indication that the session happened some time before the death of their father, Prince Albert, which happened in December of 1861. After that, they were required to wear black for more than a year. Even Alice and Louis' wedding was celebrated in mourning clothing. Soon after, the newlyweds left England for their new home in Hesse, Germany.

Logically, given the nature of the sitters, a long posing session for this painting may have been implausible. And although the technique employed here by Pope reveals a very quick execution, as opposed to his more refined style, it is highly possible that finishing the painting may have taken until the first months of 1862, becoming somewhat inopportune to deliver, since the family was by then in mourning. This may have halted the commission of a larger painting, so the sketch, enhanced as a finished picture, might have reached another collection, not that of the sitters.

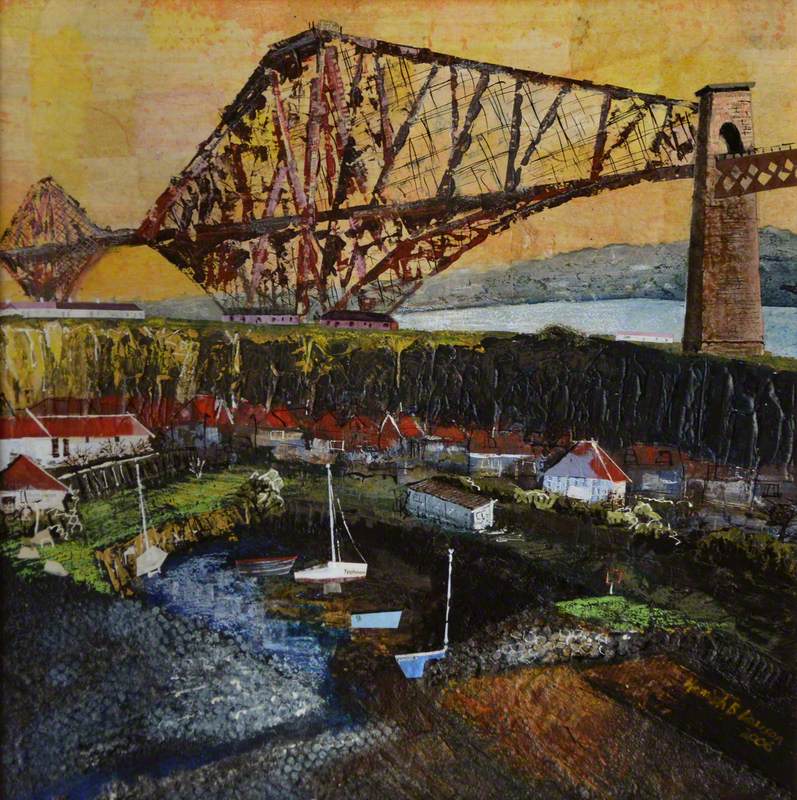

The venue

The elegant music room was located at the mansion known as Coleherne Court, Old Brompton Road, South Kensington. During those years, the house was the property of Dion Boucicault, famous actor and playwright, who possibly also let apartments or studios. By then, Pope may have rented a studio there, having as a neighbour the notable photographer Charles Thomas Newcombe, whose photographs are precisely the lead to confirm the location, which is also recorded in a label on the back of the painting.

Interior of Coleherne Court

(detail), c.1864, photograph by Charles Thomas Newcombe (1830–1912), featuring actors Toole and Bedford

The arrangement of the interior and some pieces of the furniture are a match without any doubt. They are featured in several photos of other clients by Newcombe. The timing is also circumstantially confirmed: Newcombe used the music room at Coleherne Court as the setting for his pictures right up until 1863, the year in which he built a luxurious study in the courtyard, made of glass, and specifically designed for his photography workshop.

The painter and his hand

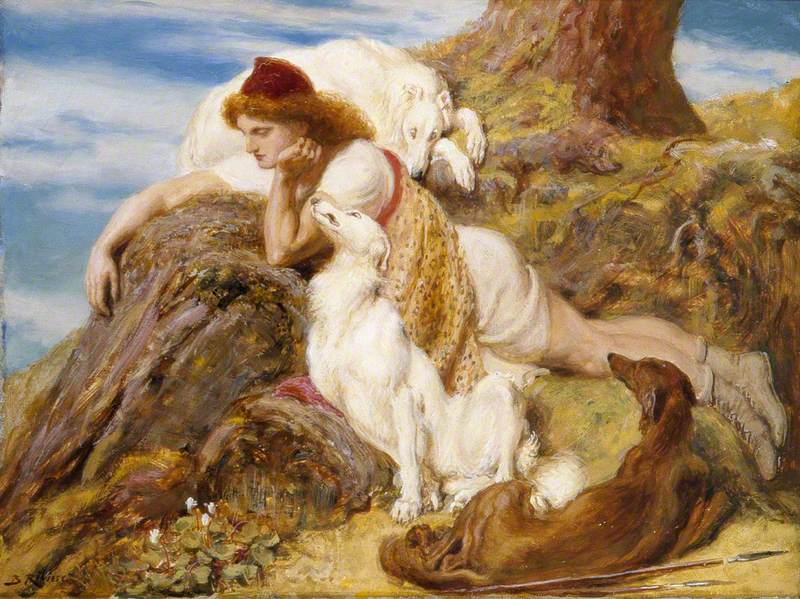

Gustav Pope came to England from Austria around 1851 at a young age. Almost the entirety of his career was developed in the United Kingdom, and his style shows exactly that: influences of leading national artists such as John Everett Millais, Lord Frederic Leighton and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema are present in his genre oeuvre. The attribution of this canvas to Gustav Pope is based on stylistic terms, as can be seen in comparative images with paintings from around the same decade.

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'The Homecoming' (right)

(detail), c.1862, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'After the Ball' (right)

(detail), c.1863, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

Within these select group of works for comparison, the general treatment of the skin, and the drawing lines of noses, nostrils, and lips are very similar. Careful Morellian analysis also reveals some other subtle details that are compatible. For instance, the characteristic shade that falls into the eyes, and the cast shadows below chin and ears, and other technical similarities such as the emphasis on the rose colouration of the skin, and the distinctive technique on the highlights over the hair.

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'Major-General Lord Henry Percy' (right)

(detail), c.1878, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'Louisa, Duchess of Northumberland' (right)

(detail), c.1867, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'The Pet Pigeon' (right)

(detail), c.1886, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

The brushstroke in the depiction of fabrics and clothing is one of the features that better allows to differentiate one painter from another. In this regard, a comparison with works like The Pet Pigeon, The Judgement of Paris, and a portrait of George Percy, 5th Duke of Northumberland, reveals almost for sure the same hand. Note the broad lines of colour to denote shades and shining surfaces, and the angular structure of the wrinkles on the fabrics.

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'The Pet Pigeon' (right)

(detail), c.1886, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'The Judgement of Paris' (right)

(detail), c.1889, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

The depiction of accessories is also coherent in style and technique. Objects such as furniture, reliefs, and floral motifs are rendered with broad strokes and blurred detail. Often a pointillism method was used to replenish the surfaces, most notably over the carpet.

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'After the Ball' (right)

(detail), c.1863, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

Comparison of 'The Music Room' (left) and 'George Percy, 5th Duke of Northumberland' (right)

(detail), c.1866, oil on canvas by Gustav Pope (1831–1910)

The Music Room, and in general all of Pope's production from the 1860s, belong to a period of search for a definitive style in the career of the artist. Gustav Pope's main interest during this time gravitated around domestic subjects and an earlier form of social realism. His success at the Royal Academy with his painting A Rainy Day in 1862 made him a more established painter among important patrons, several from noble families like the Norfolks and the Percys of Northumberland. Pope was to find his mature style during and after the 1870s, with an approximation to the Aesthetic movement and the Pre-Raphaelite second wave. He also used to enrich his subjects with symbolism, referencing within his works his philosophical thoughts about life, politics, and society.

Gustav Pope was enormously talented and able to translate complex feelings into painterly existence, with an utmost sense of beauty and genuineness. The debt in art literature to Pope for his outstanding contribution to the arts is also overdue for many other artists of the nineteenth century without a proper monograph.

César Guerra-Acevedo, psychologist and art researcher