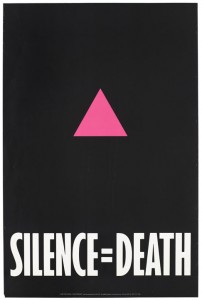

The classical world has long provided artists with a repository of recognisable narratives, motifs and forms from which to populate their work. These allusions and references position an artist’s work in an established and respected canon and imbue the piece with cultural sophistication and currency. This, in turn, can also license subversive material that would otherwise be considered unacceptable to discuss or portray.

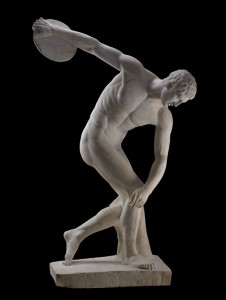

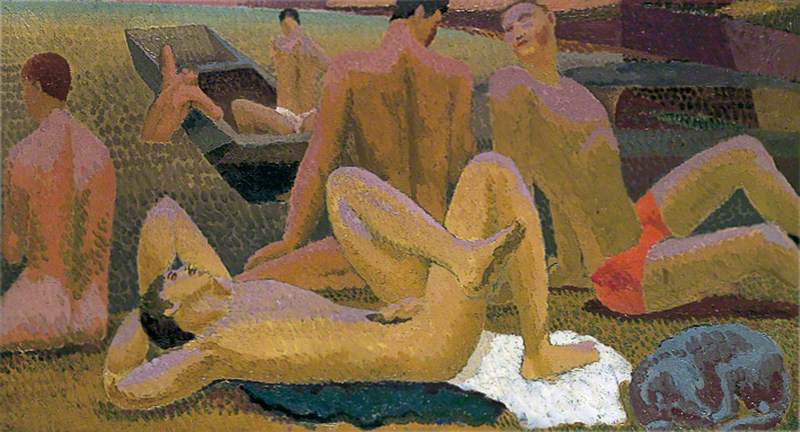

The notion of ‘Greek love’ to describe the homoerotic customs, practices and attitudes of the ancient Greeks has permitted artists to explore male and homosexual love in their work without fear of persecution. The British painter Keith Vaughan (1912–1977) is one example. Vaughan used the Greek landscape and mythological scenes to express his desires, and the shades of white and yellow which often constructed his painted figures are reminiscent of the marble statues of antiquity.

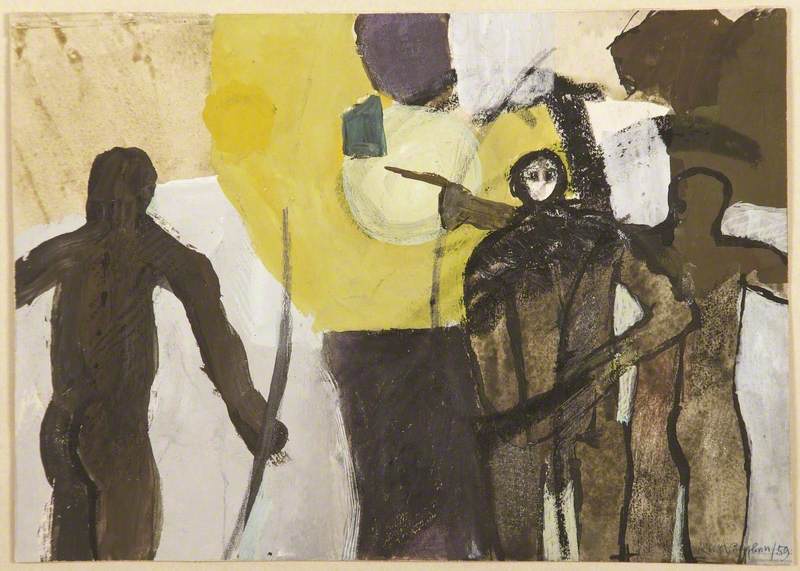

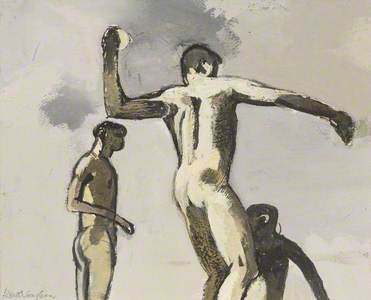

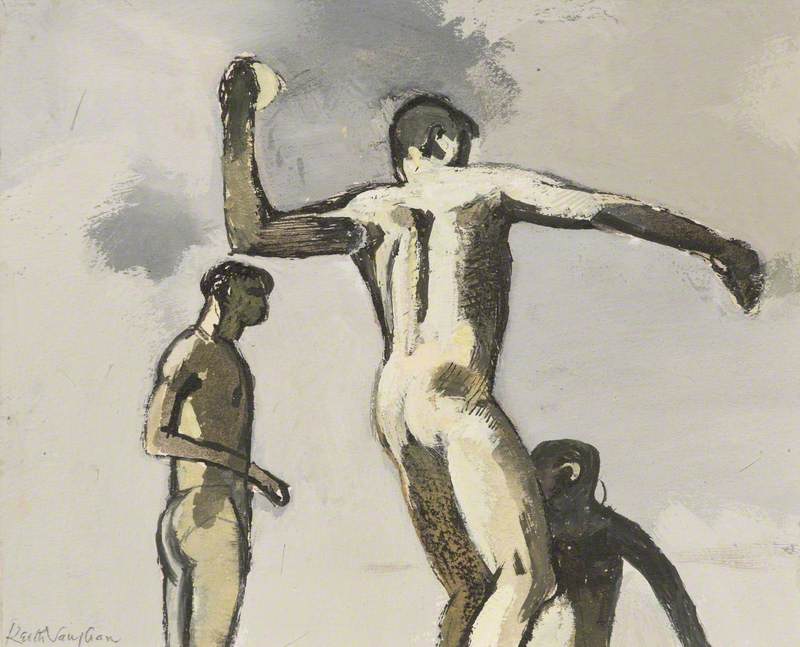

Figure Throwing at a Wave

1950

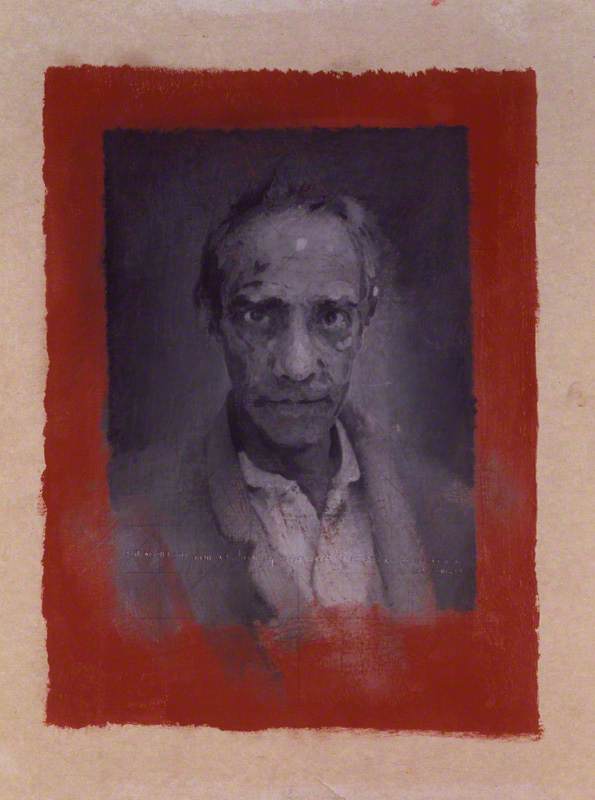

John Keith Vaughan (1912–1977)

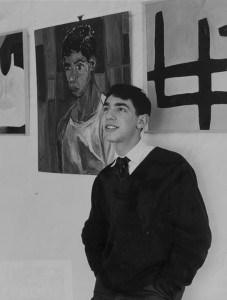

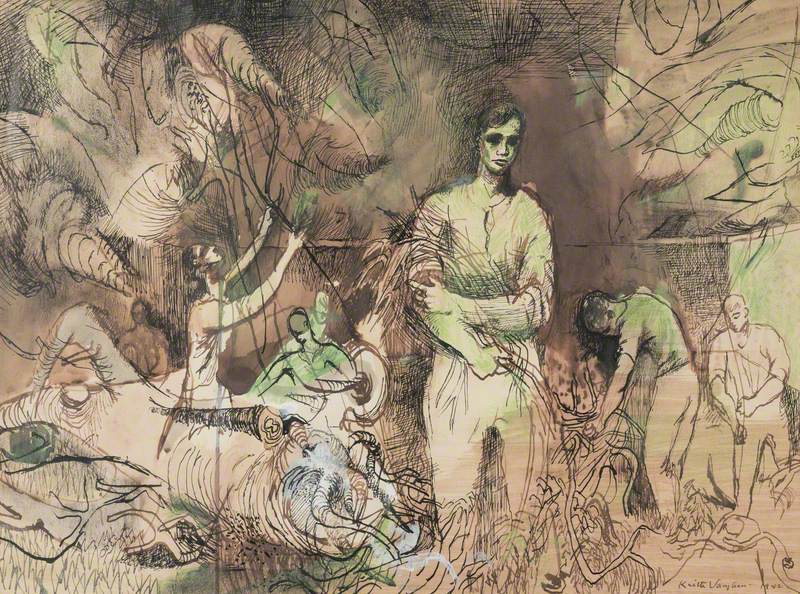

A conscientious objector in the Second World War, Vaughan joined the neo-romantic circles of the immediate post-war years alongside his friends and fellow artists Graham Sutherland and John Minton. Vaughan’s work moved further towards abstraction in later life and his favourite theme of the male nude in a landscape setting became increasingly grand yet more simplified.

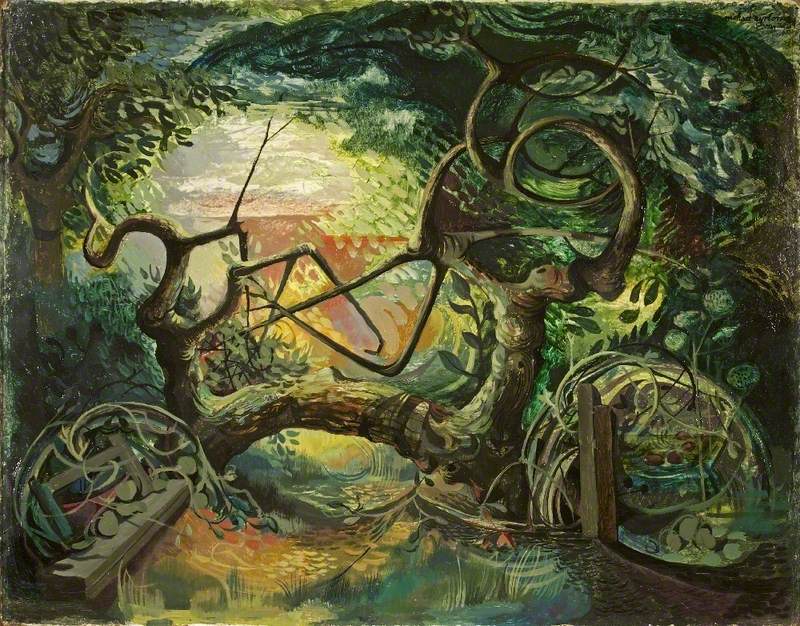

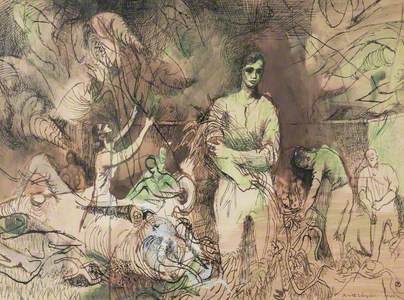

The Garden at Ashton Gifford

1942

John Keith Vaughan (1912–1977)

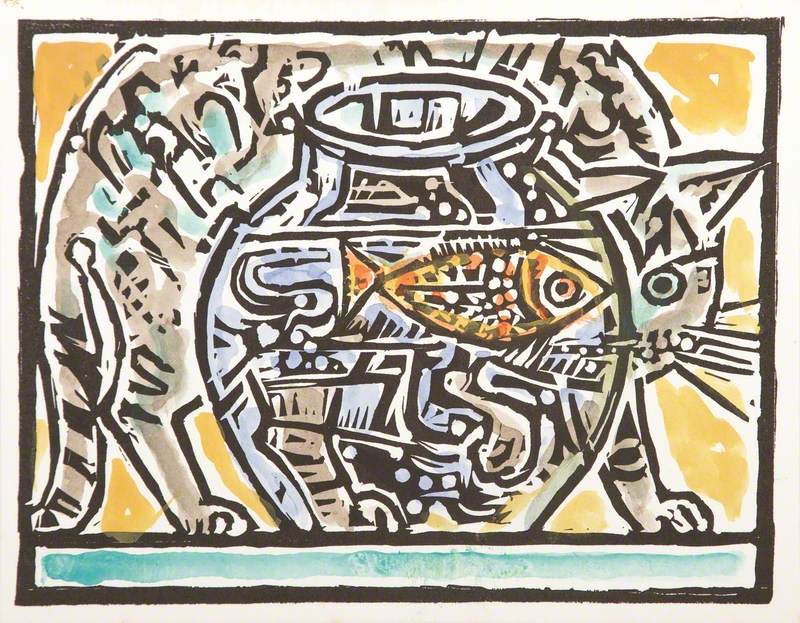

Landscape with Seated Figure

1964

John Keith Vaughan (1912–1977)

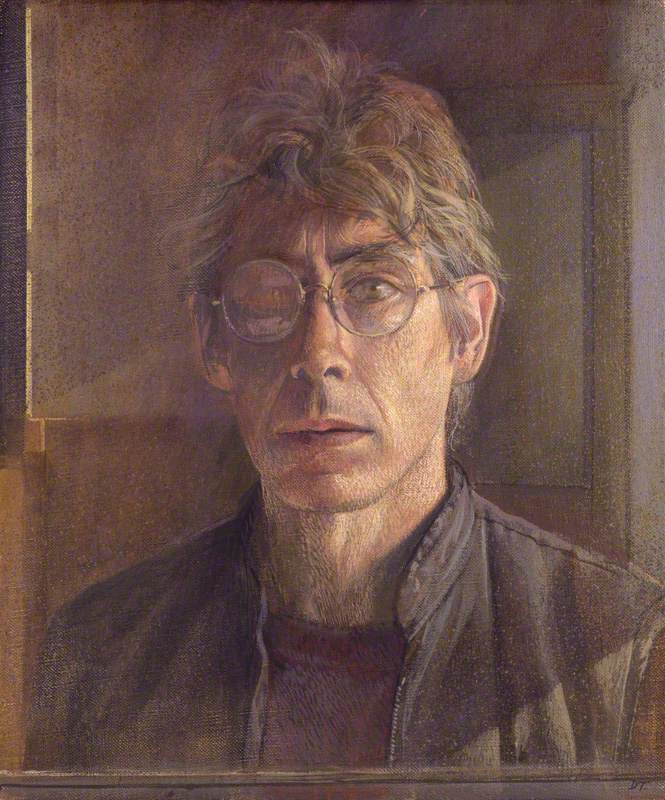

Vaughan documented his life and innermost thoughts in a series of journals written from 1939 until his suicide in 1977. These journals reveal Vaughan’s mental anguish as he struggled with his career, health and emotional turmoil. Vaughan wrote consciously for a future reader in hopes of informing them of, and even saving them from, the mental torture that he had suffered throughout his life.

Though many of the ancient references in Vaughan’s work can be understood to convey codified personal meanings related to his homosexuality, Vaughan was also invested in creating images ‘which would embody the life of our time’, and in constructing a notion of universal humanity.

As the classical world has long been considered the birthplace of western civilisation, and Greek mythology contains many foundational narratives, antiquity can act as a means of representing some sort of common human experience. Vaughan struggled throughout his life with reconciling his personal impulses with the monumental aims of his work and used the ancient world to express this duality.

Vaughan travelled to Greece on three separate occasions, and his first encounter with the Aegean Sea in 1960 led to a predominance of blue in his work. Vaughan showed a clear interest in antiquity in his journals, for example, commenting on the ‘clear layers of Greek, Roman and Byzantium building’ visible at Corinth.

Following his first visit, Vaughan painted several pieces inspired by the Greek archipelago. In 1961, Vaughan painted Mykonos, Greece, an island now famous for its LGBTQ+ nightlife. The fact that Vaughan chose to paint Mykonos out of hundreds of islands is almost certainly related to the island’s personal significance to him. Mykonos’ position in the classical canon also meant that it was an acceptable means of alluding to homosexual life and culture.

The island of Delos was the subject of a 1962 piece by Vaughan. Delos is one of the world’s most important archaeological sites, having been a holy sanctuary for millennia and the meeting-place for the Athenian Empire in the 5th century BC. The island is of universal historical importance, and the horizontal line that runs through the middle of the work creates a sense of centrality and balance. This highlights the importance of Delos and antiquity in the history of mankind. The islands of the Aegean evidently ranged in meaning in Vaughan’s work, moving between personal commentary and wider social significance.

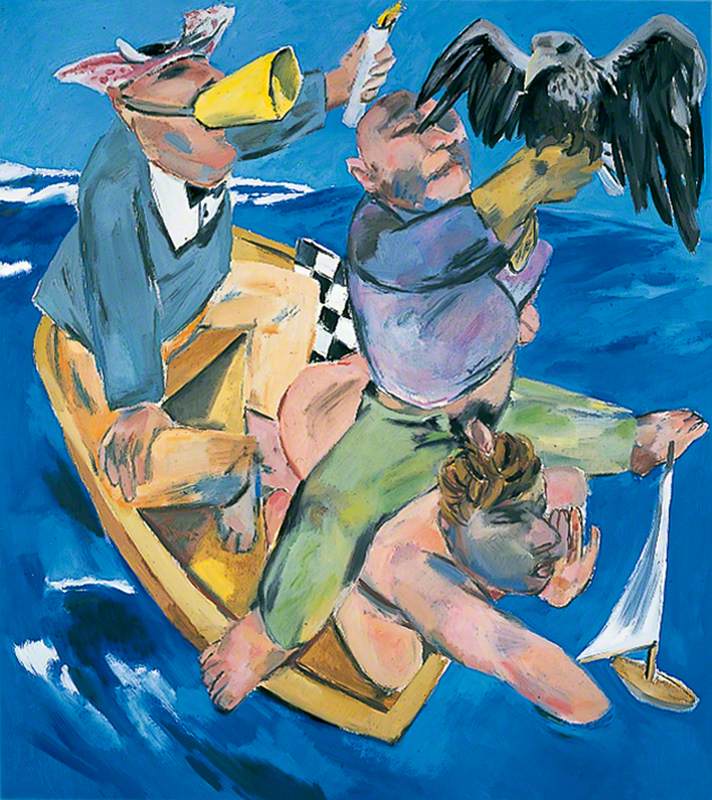

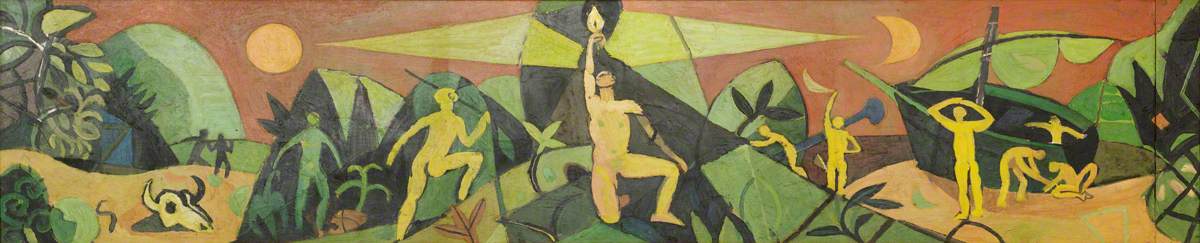

Vaughan also frequently used mythological narratives in his work. In 1951, Vaughan was commissioned to paint a mural for the ‘Dome of Discovery’ in the Festival of Britain. The exhibition’s theme centred around the idea of British initiative in exploration and discovery. Vaughan chose the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur to represent this.

Theseus was the founder-hero of Athens, who battled and overcame foes that were identified with archaic religious and social orders. Theseus was thus seen to represent major social transformation, which would explain why Vaughan chose this myth to represent the exciting innovation of post-war Britain.

This myth could, however, also have had personal significance to Vaughan. The Minotaur can be understood as a symbol of the civilised individual’s internal conflict with their animal nature and bestial desires. This could relate to Vaughan’s struggle with living in mid-twentieth-century Britain, as homosexuality remained illegal until 1967. Vaughan had trouble in reconciling his ‘honours, distinctions, successes etc., [with being] … a member of the criminal class’.

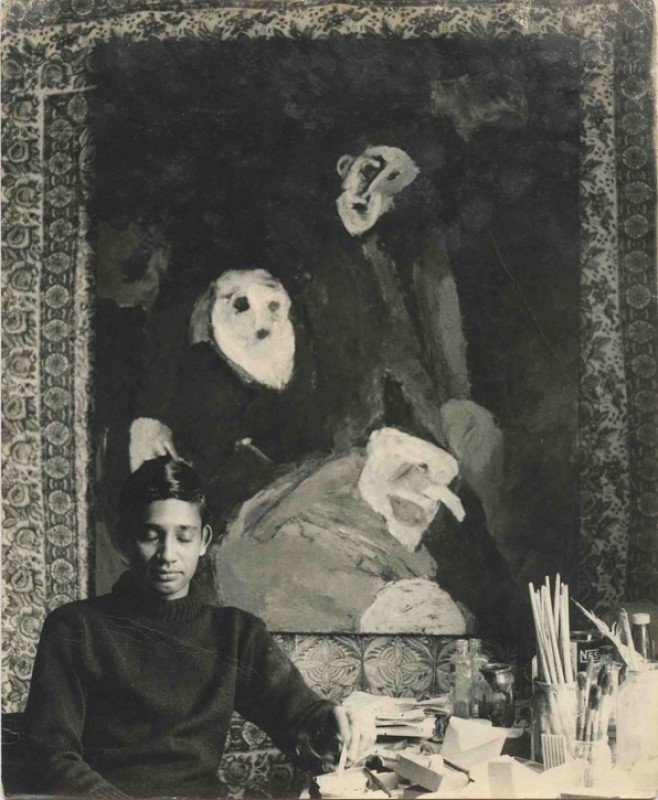

Theseus

(final study for the 'Dome of Discovery' at The Festival of Britain) c.1950

John Keith Vaughan (1912–1977)

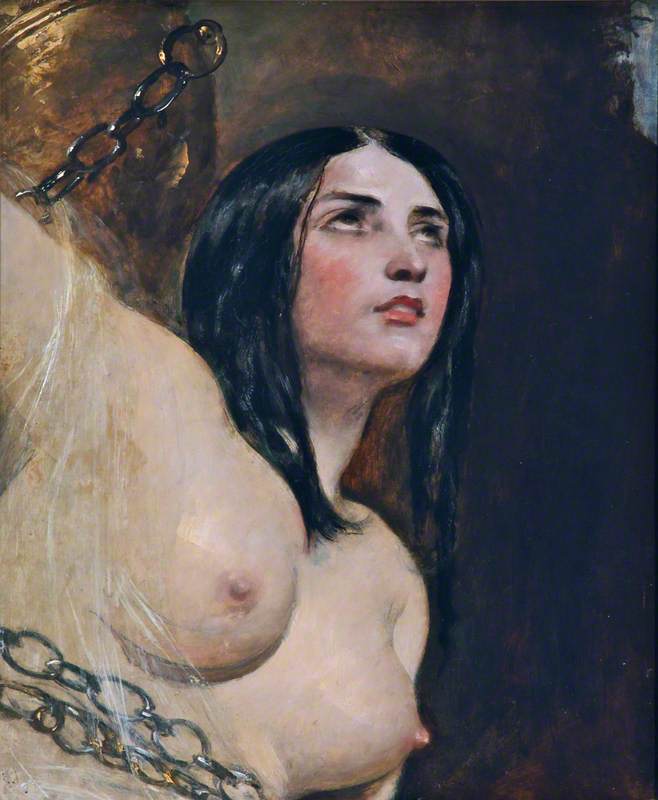

Another mythological narrative used by Vaughan was the death of the Laocoön. Laocoön was a Trojan priest who was killed alongside his two sons by a giant serpent as divine punishment. Laocoön’s tragic fate was famously depicted in the ancient statue Laocoön and His Sons, produced between 27 BC and AD 68 (and seen here in an early-nineteenth-century copy).

The ancient sculpture has been described by classicist Nigel Spivey as ‘the prototypical icon of human agony’ in western art. Vaughan painted several versions of the Laocoön Group such as Study for a Laocoön Group II and Study for a Laocoön, VII, both produced in 1964. The statue’s significance in art history surely appealed to Vaughan’s desire to represent universal experiences and emotions in his work.

Vaughan however also wrote that ‘for him… [the idea behind the Laocoon myth] is that it represents… man’s conflict with his environment… with himself’ and the evils of temptation. Like Theseus and the Minotaur, Vaughan’s reimagining of the Laocoön Group could thus also be an exploration of his personal struggle with experiencing homosexual desire in the era in which he lived.

The intricacies of Vaughan’s personal struggles were perhaps lost on viewers at the time, but the universal topics meant that anyone could find relatability in his work, and the ancient imagery sanctioned problematic (at that time) sexual material and allusion. The creation of this duality perhaps also provided Vaughan with some comfort as he grew increasingly dissatisfied with life. Vaughan’s merging of his sexual struggles with the classical canon transformed his personal problems into powerful examples of the human condition on par with the great narratives and culture of the ancient world. The gay man was thus humanised and made relatable by Vaughan, achieving both the monumental aims of his work and his personal journals.

Flora Doble, Art UK’s Operations Officer