From the Renaissance onwards, many western European painters relied especially on blue paper to provide balanced, mid-toned backgrounds. This helped them to emphasise effects such as strong light and dark contrasts.

Across several centuries, it remained such an important medium that The Courtauld, London, has made it the subject of an exhibition: 'Drawn to Blue: Artists' use of blue paper'. It brings together exquisite examples of drawing and highlights the latest research into materials used by a range of leading artists, from Tintoretto to J. M. W. Turner and beyond.

Saint Mary Magdalene

1628–c.1632

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

From infrared to x-rays, advances in technology have allowed us to peer beneath the surfaces of old masters to reveal hidden secrets and allow greater insights. Similar techniques are now being used to shed light on how artists through the ages have used paper, particularly coloured sheets.

In Europe, blue paper first appeared in northern Italy during the fourteenth century. It was derived from discarded rags, especially those dyed blue, often to conceal dirt and stains on work clothes. Such garments included protective gear, including aprons and smocks, worn by manual labourers, and sailors' uniforms.

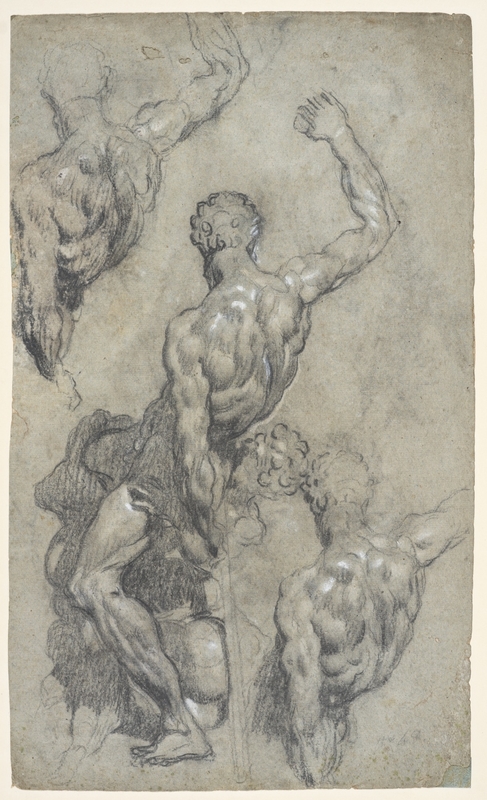

During the following hundred years, blue paper was adopted by Italian artists, notably in the region around Venice. Renaissance artists, including those based in the productive workshop of Venetian master Jacopo Tintoretto, used the medium of drawing to copy work by other masters. A fine example comes with his confident, detailed Studies after Michelangelo's 'Samson and the Philistines', one of several sketches Tintoretto made of his fellow Italian's celebrated yet unfinished sculpture (evidence in this drawing suggests it was based on a model).

Studies after Michelangelo's 'Samson and the Philistines'

c.1545–c.1555

Jacopo Tintoretto (c.1518–1594)

Here, Tintoretto has captured the Florentine genius's musculature and twisting pose using charcoal and lead white, with the blue background ideal for exploring these figures' shade and volume. Unfortunately, partly due to the use of natural dyes, paper from this period tends to discolour over time, with blues tones especially prone to fading. Such pages can now appear as brown, grey, buff or green.

Previously, this work in The Courtauld's collection was believed to have been made on green-grey laid paper, meaning it was made using a traditional process where wire-sieve moulds were dipped into a pulp of wet fibres. Now, though, Tintoretto's work has undergone careful examination using a pair of non-invasive techniques: a video spectral comparator that enables examination of individual fibres and reflectance spectroscopy can determine the actual dyes used. The institution's project comes as a collaboration with the J. Paul Getty Museum, which has pioneered this ground-breaking research.

Study of a Male Figure Bending Forward

1575–1585

Jacopo Tintoretto (c.1518–1594)

For her exhibition, Rachel Hapoienu, Assistant Curator of Works on Paper at The Courtauld, has revealed Tintoretto actually used variegated blue paper, meaning it was formed, like much blue paper of its time, from a mix of different coloured fibres (including blue) that had then been dyed that colour. This is key information, as an artist's choice of paper is tied to the drawing's function. When depicting a three-dimensional figure on a flat surface, blue paper allowed an artist to use both black and white drawing materials. 'Blue paper was the ideal colour for modelling and studying the depiction of volume,' Hapoienu says. 'As a result, blue paper was often used for figure studies, as in drawings in the show by Barocci and Tiepolo.

'It was also an important tool in workshops training future generations of artists, who were instructed to draw after sculptures in the round before graduating to drawing from live models, as in the Tintoretto drawing. I hope the show will remind viewers that for artists, the paper they select is not just a neutral background, but integral to the artwork itself.'

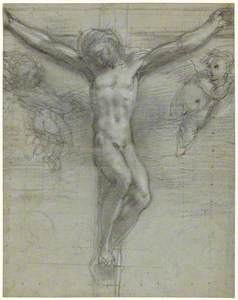

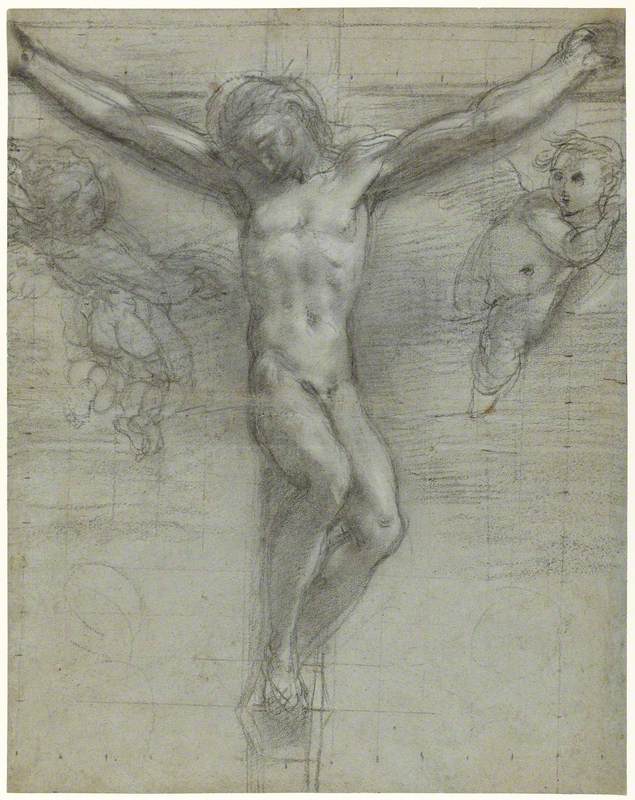

Study for Christ on the Cross with Two Angels

(recto)

Federico Barocci (1535–1612)

By the late sixteenth century, the use of such paper had spread across the continent. Based predominantly in his birthplace of Urbino, Federico Barocci was widely regarded as central Italy's finest artist of his time. Many of his effects were achieved through the use of coloured chalk, anticipating the preference for blue paper by pastel artists two centuries hence, though for his Study for Christ on Cross with Two Angels (recto) he limits himself to black and white.

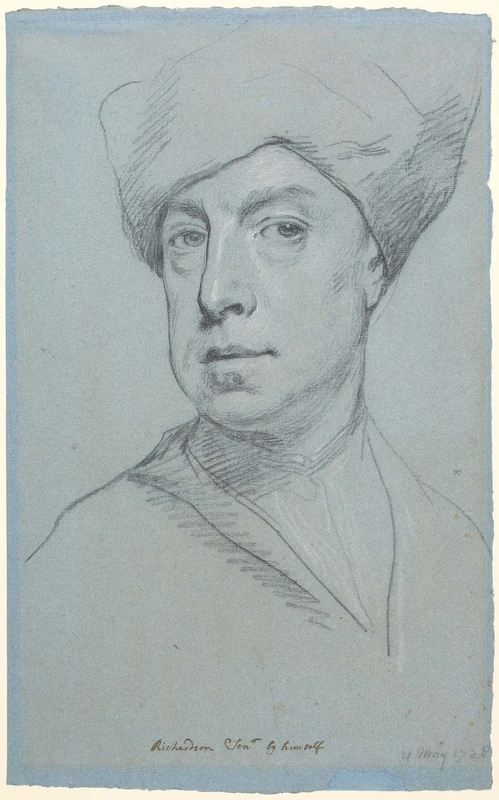

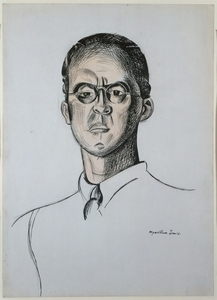

During the eighteenth century, blue paper was still widely used, especially in England and France, perhaps inspired directly by early users such as Tintoretto. One such practitioner was the English portrait painter, Jonathan Richardson the elder. His striking Self-Portrait actually makes use of the cheapest kind of blue paper then available, a rough-quality wrapping for goods such as sugar. Yet its subtle background allows Richardson to make the most of his black and white chalks.

While a leading artist of his time, the portraitist became better known for his writings, including An Account of Some of the Statues, Bas-Reliefs, Drawings and Pictures in Italy (1722). He also built up a collection of 4,700 works, including from Venetian Renaissance artists such as Tintoretto and Veronese, leading The Courtauld to suggest this work may have been a form of homage.

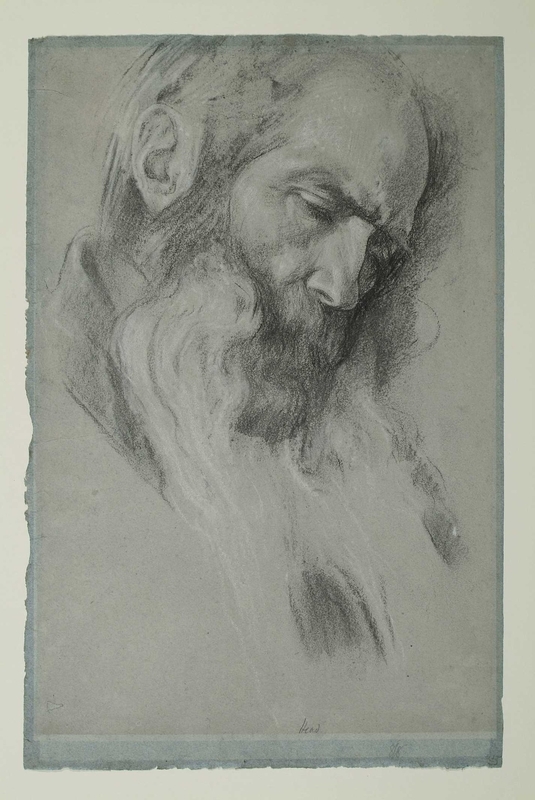

Portrait of One of the Artist's Sons

1751–1753

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

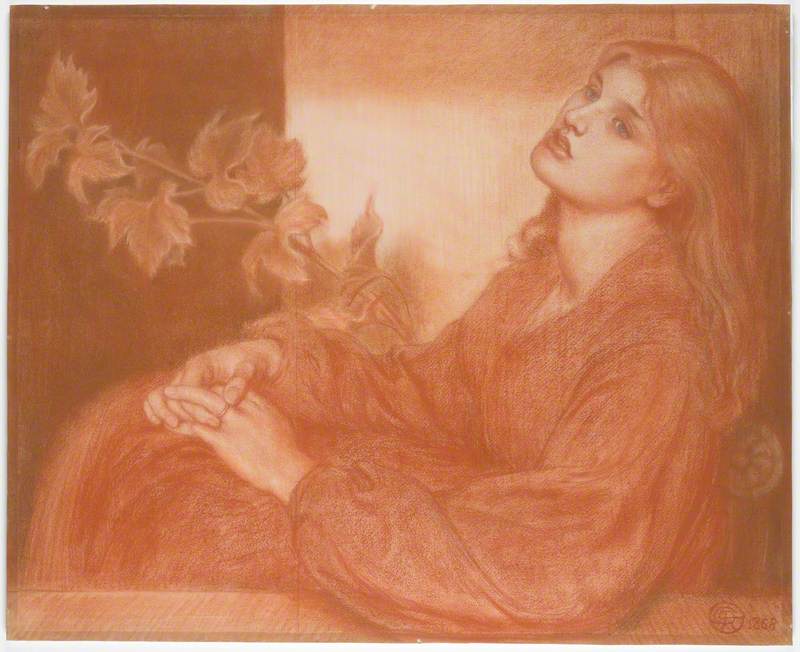

Indeed, blue paper continued to be used in the city where it was originally popularised, certainly by the great eighteenth-century master Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, such as in the piece titled Portrait of One of the Artist's Sons. This comes from a series of head studies drawn as preparation for painting the ceilings of the Würz Residence, Bavaria, where Tiepolo was assisted by his sons Giovanni Domenico and Lorenzo. The latter often modelled for his father, so is believed to be the subject of this masterful work, where Tiepolo's use of warm red chalk stands out against the cool blue background.

The subsequent century saw advances in paper production, firstly through developments that allowed for smoother surfaces. Wove paper was first created by hand using a much finer mould, later replaced by paper machines. From the 1830s, J. M. W. Turner increasingly used a variety of coloured papers for sketching. On his travels, he usually took a supply of blue stock from the painter's preferred English papermaker, George Steart of De Montalt Mill, Bath.

View of Bregenz (formerly 'View of Locarno')

1840

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

However, The Courtauld believes View of Bregenz, made during the summer when he returned to the continent, was drawn on wove paper bought more locally. On his journey to Venice, Turner stopped at the historic Austrian town famed for its ancient religious buildings high above Lake Constance. In this expressive depiction, the blue allows him to leave areas of sky and water untouched, while pink and white gouache bring out the sunlight on Bregenz's rooftops.

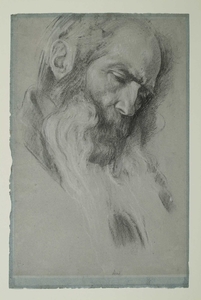

Study for 'Michelangelo Nursing His Dying Servant': Head of Servant

c.1861

Frederic Leighton (1830–1896)

By now, papermakers were finding access to more impactful and longer-lasting dyes for their blue paper, which continued to be valued by artists from the late nineteenth century and onwards. Frederic, Lord Leighton was one of the most influential British artists of the Victorian era, known for his depictions of bodies and landscapes that drew on Neoclassicism. Many of his preparatory drawings were made on such paper, including this detailed figure, Study for 'Michelangelo Nursing His Dying Servant': Head of Servant.

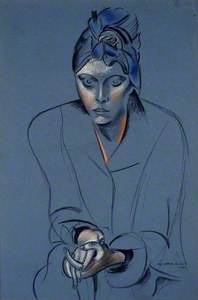

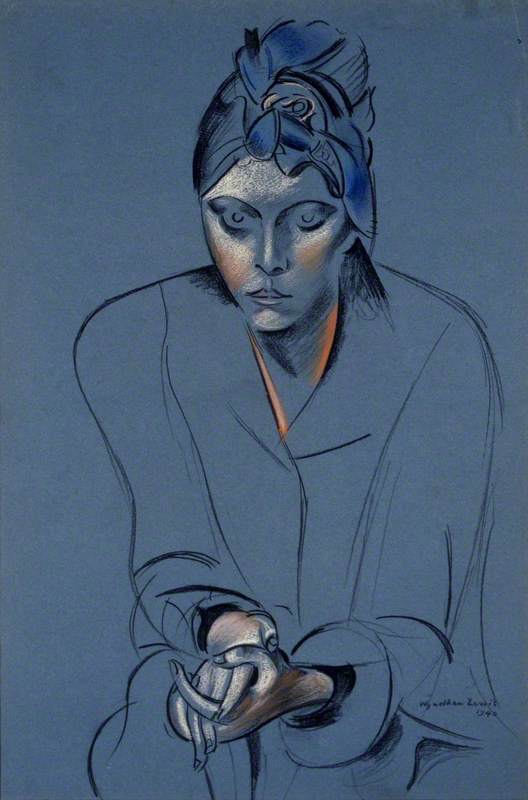

A Portrait of the Artist's Wife, 'Froanna'

1940

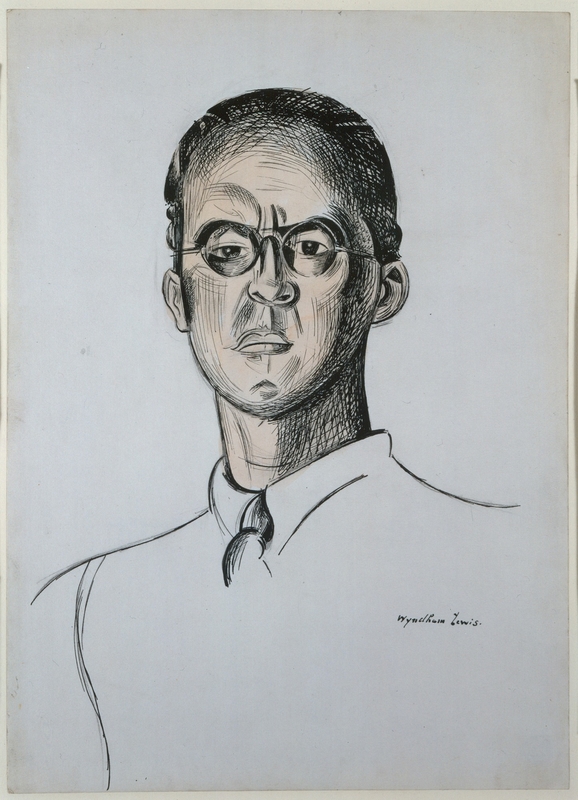

Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957)

During the twentieth century, another fan of blue paper was Vorticism founder Wyndham Lewis. He used it for A Portrait of the Artist's Wife, 'Froanna', its bright tone capturing Gladys Hoskins' intensity. During the Second World War, this couple were based in the United States, where Lewis apparently bought this stock in a drugstore. Elsewhere, The Courtauld has examined another of his drawings in its collection and on show in 'Drawn to Blue,' finding the paper was dyed with the mineral azurite.

Having used this initial research as the springboard for its current exhibition, Hapoienu aims to examine further works to identify how each support was made (including those that don't appear blue), giving us deeper insights and drawing us closer to how artists operated in previous centuries.

Chris Mugan, writer

'Drawn to Blue' runs at The Courtauld, London until 26th January 2025

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation