'Everyone must choose their own way – and mine will be the way of colour,' said George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931), one of the four 'Scottish Colourists' – along with Samuel John Peploe (1871–1935), John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961) and Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell (1883–1937) – who took Scottish painting to a wholly different level in the early twentieth century.

When he said this in 1919, Hunter was 42 and had been painting all his adult life. What had changed to prompt this open declaration?

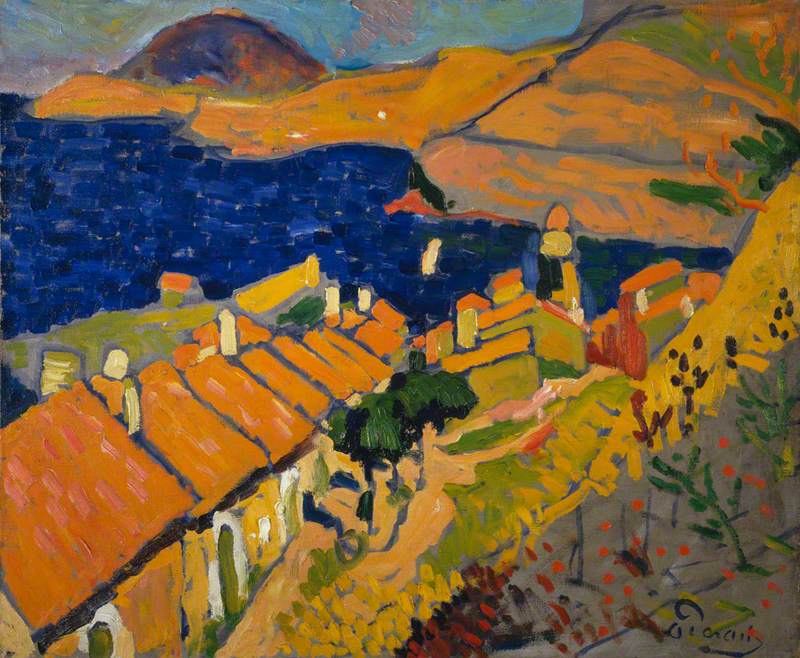

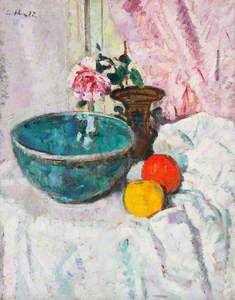

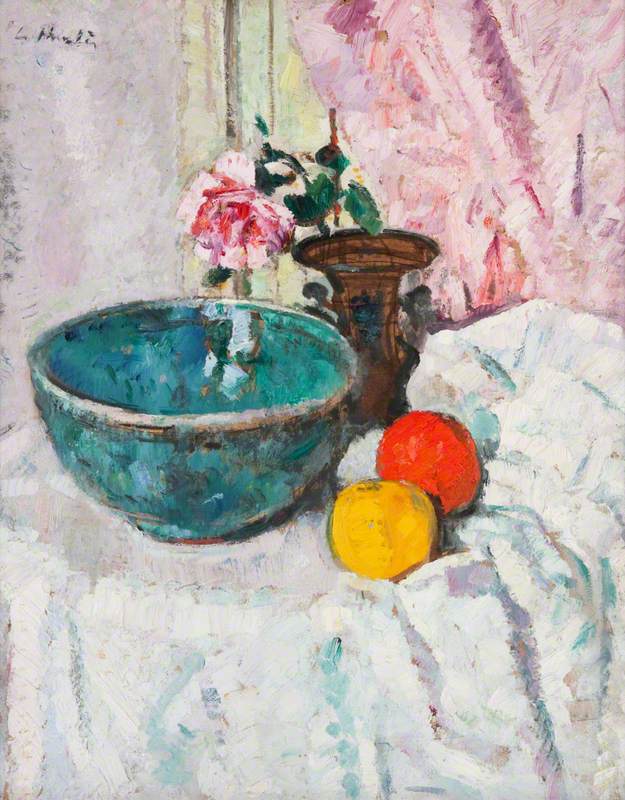

Pink Rose, Fruit and Still Life

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Unlike the other Colourists, Hunter grew up in California (having emigrated with his parents aged 15) and became a professional illustrator in San Francisco. He counted as friends the talented writers Jack London (1876–1916) and Gelett Burgess (1866–1951), journalist Will Irwin (1873–1948), and photographer Arnold Genthe (1869–1942), and experienced far greater freedom of expression and thought, than the cultural constraints faced by Peploe, Fergusson and Cadell in Scotland. In San Francisco, Hunter and his friends keenly discussed philosophy, literature, art and music and they were surprisingly well-informed, some travelling to Paris and returning with first-hand news of the latest developments. The devastating earthquake and fire in 1906 ended Hunter's carefree, lively bohemian life in San Francisco, forcing a return to Scotland.

Still Life with Roses in a Vase and Fruits in a Bowl

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Hunter was younger than Peploe and Fergusson, but they were all in Paris at the same time, experiencing French avant-garde developments as they were happening. Yet the four 'Scottish Colourists' were never a movement or a school – the name first appeared as the title of a 1948 exhibition and it has carried on ever since. Contact between Hunter and the others was at best sporadic.

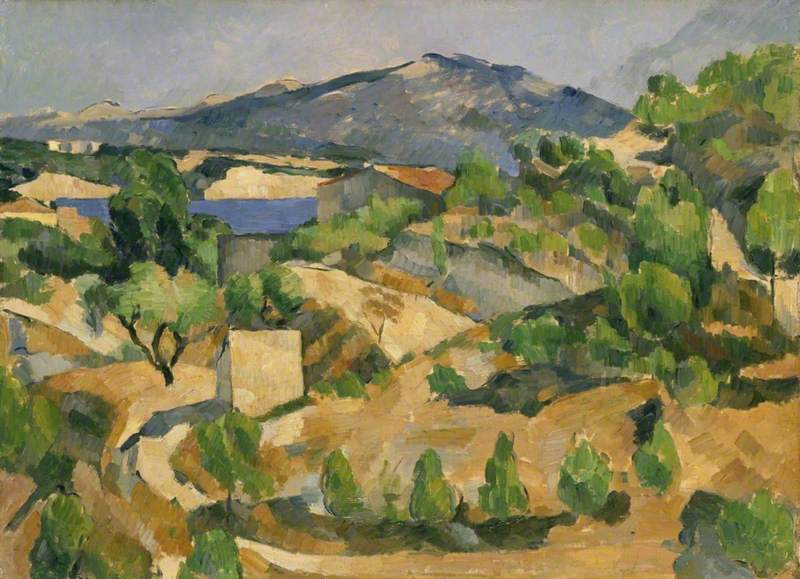

Hunter's declaration on colour is explained by his friend and art dealer, Dr T. J. Honeyman (1891–1971), who cited him as among the first artists in Britain to completely grasp what Paul Cézanne (1838–1906) was attempting to do with his complex experimentation with pure colour to build form and perspective.

The François Zola Dam

1878–1879 or 1883–1884

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

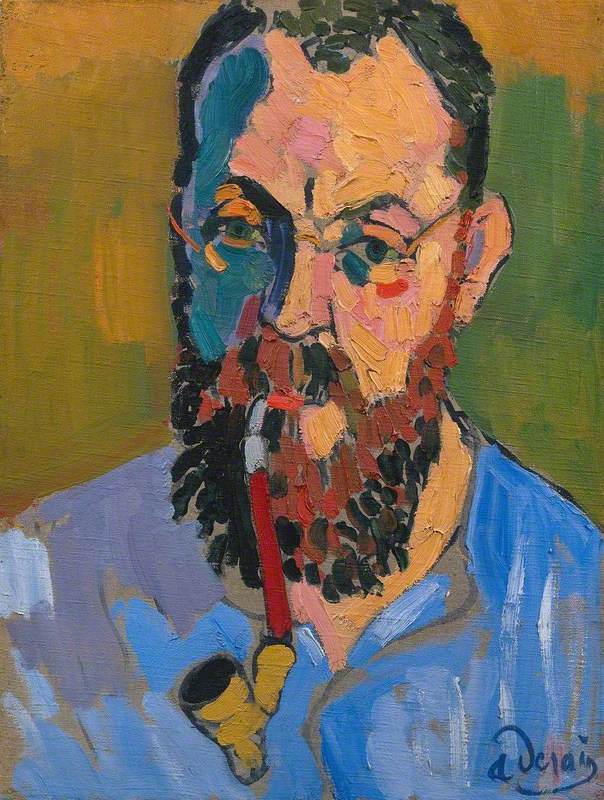

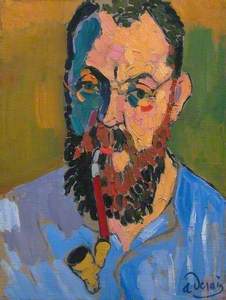

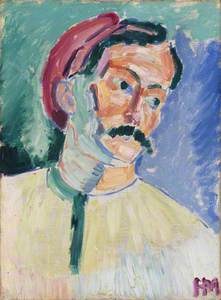

When Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and André Derain (1880–1954) of the Fauves ('wild beasts') movement raised colour to new heights between 1905 and 1910, they emphasised strong colour over mere representation of reality. From a single incident, Hunter's belief in their challenge pushed him to startling results.

In the winter of 1907, Hunter experienced raw colour first-hand in the avant-garde art of Matisse and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) hanging in the Paris home of the American writer Gertrude Stein (1874–1946), an important early patron of these artists. A friend from San Francisco, Alice B. Toklas (1877–1967), who famously became Stein's partner, took Hunter to see the art collection. She related that he was profoundly shocked and wished he had never seen the pictures. Nevertheless, he could not let go of what he'd seen. His friend Gelett Burgess explained a similar startling reaction on interviewing Matisse in his studio in 1910:

'You turn from his pictures, which have so shockingly defied you, and you demand of other artists at least as much vitality and originality – and don't find it!'

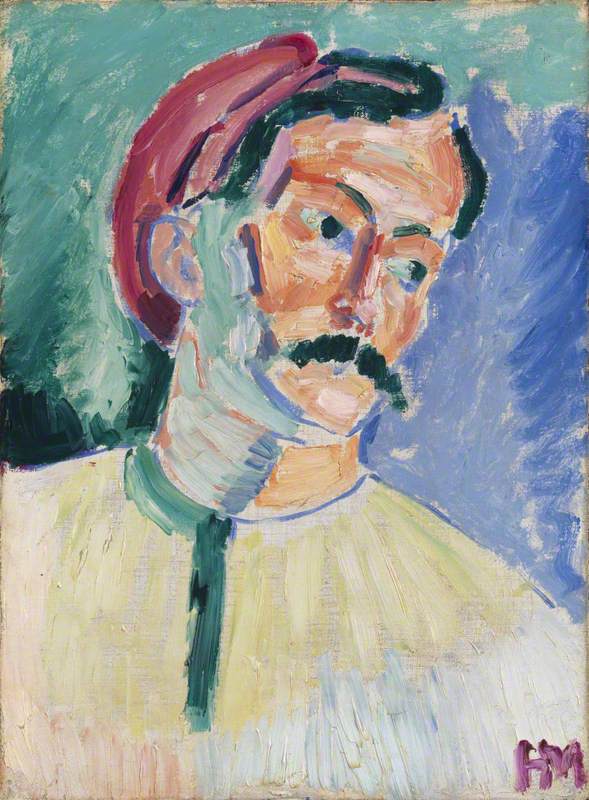

Hunter's early painting Old Dog Seated by a Tree and André Derain by Matisse in 1905 clearly show the artistic gulf between the two painting styles, but they also demonstrate how brilliant the transition in Hunter's art was over the coming years.

His route to success ran parallel to that of Peploe and Fergusson in pre-war Paris, whose reactions to Matisse, the Fauves and Cubist developments were more immediate and with different outcomes. Having received no formal art training, Hunter took longer to process it in a practical way but it was worth the wait.

By 1914 and painting in northern France, Hunter had graduated to breezy little beach scenes with figures, applying blocks of colour to build form.

From 1913 until 1918 he painted a series of still life with objects in bold colour against a dark background.

Honeyman observes in his 1950 book Three Scottish Colourists – Peploe, Cadell, Hunter:

'Style in painting is formed in two ways, first by a study of pictures and second by the observation of Nature. If the latter is inadequately performed we continue to receive the familiar 'in the manner of' production. From personal knowledge, I can vouch that all three artists in the full exercise of their talents turned to the prime source of inspiration – Nature.'

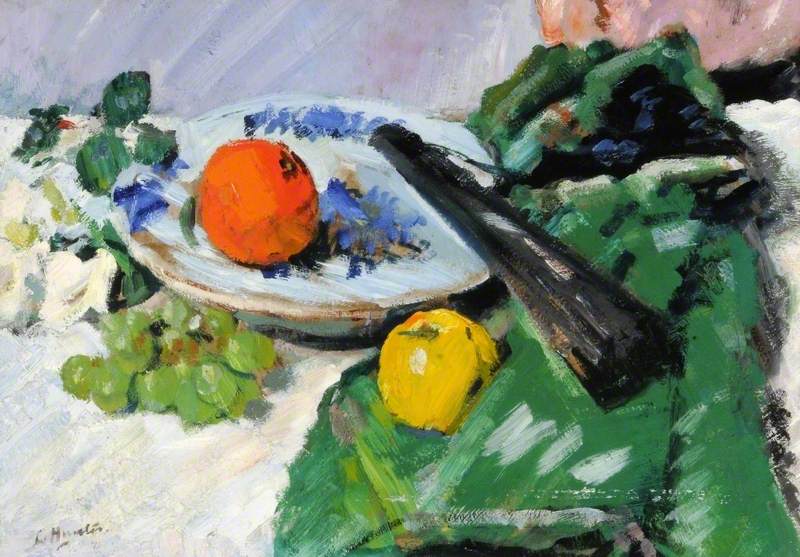

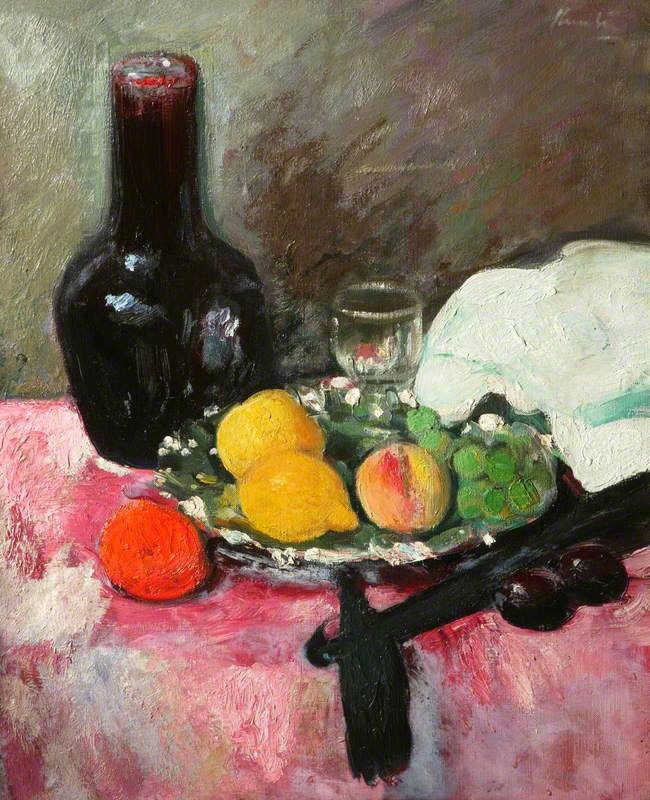

Still Life with Half-Peeled Lemon

1919

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

In 1919 Hunter produced Still Life with Half-Peeled Lemon. Steeped in Cézanne's concepts, Hunter took the essence of a painting he knew well – a Dutch seventeenth-century painting, Still Life: Silver-Gilt Goblet and Bowl of Fruit by Willem Kalf (1619–1693) – and transformed it with areas of bold colour and sweeping brushstrokes to create form. Hunter was finding 'the way of colour'.

Still Life: Silver-Gilt Goblet and Bowl of Fruit

c.1656–1660

Willem Kalf (1619–1693)

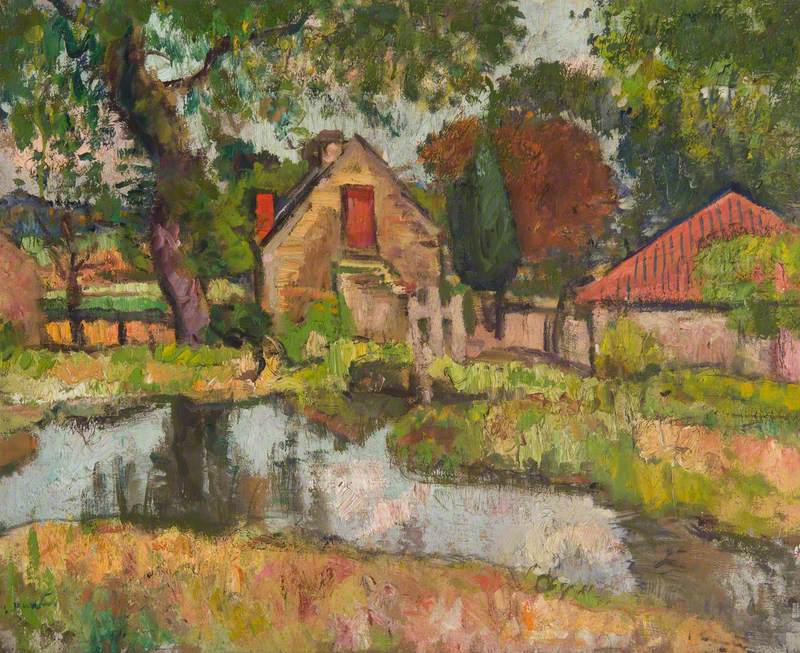

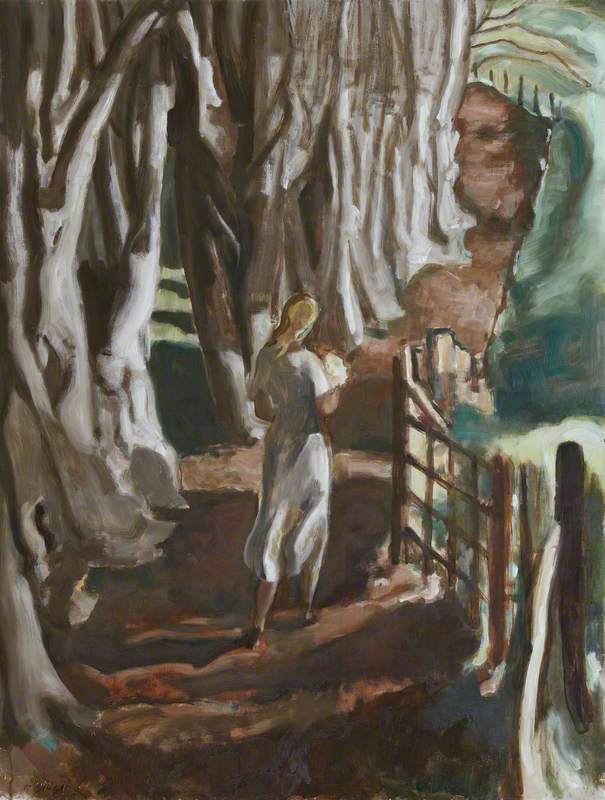

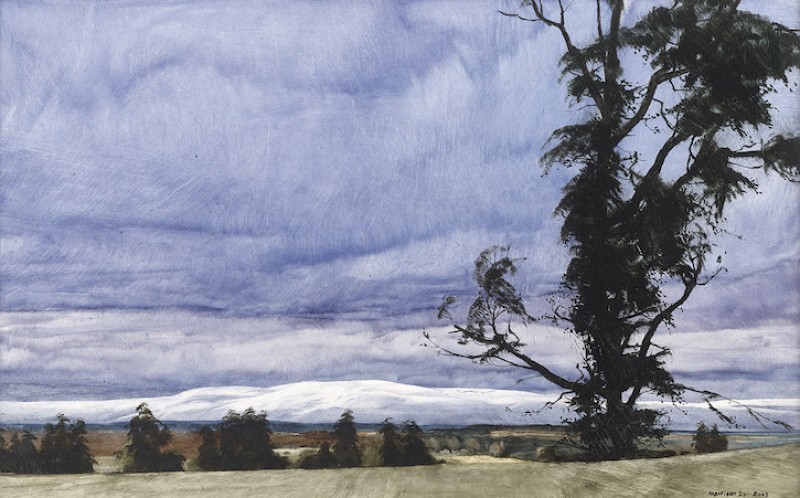

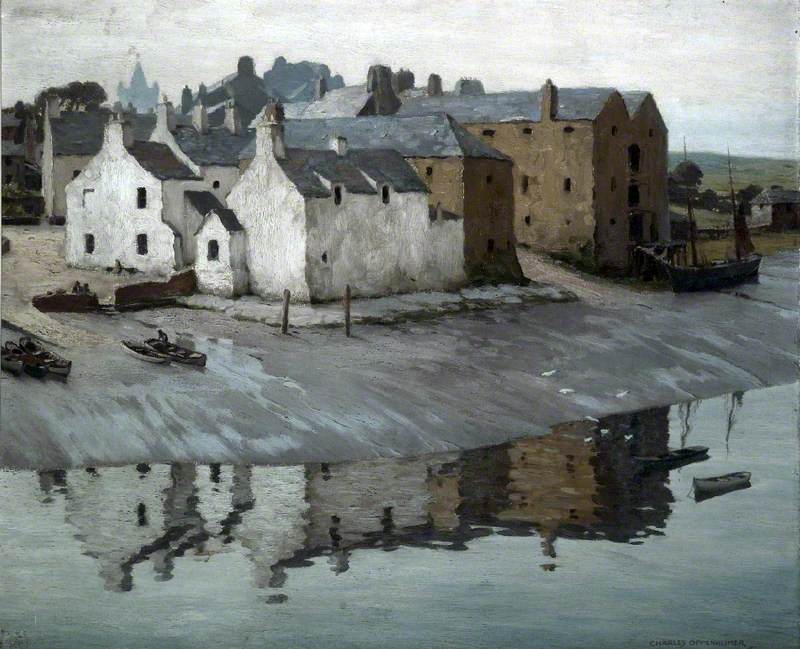

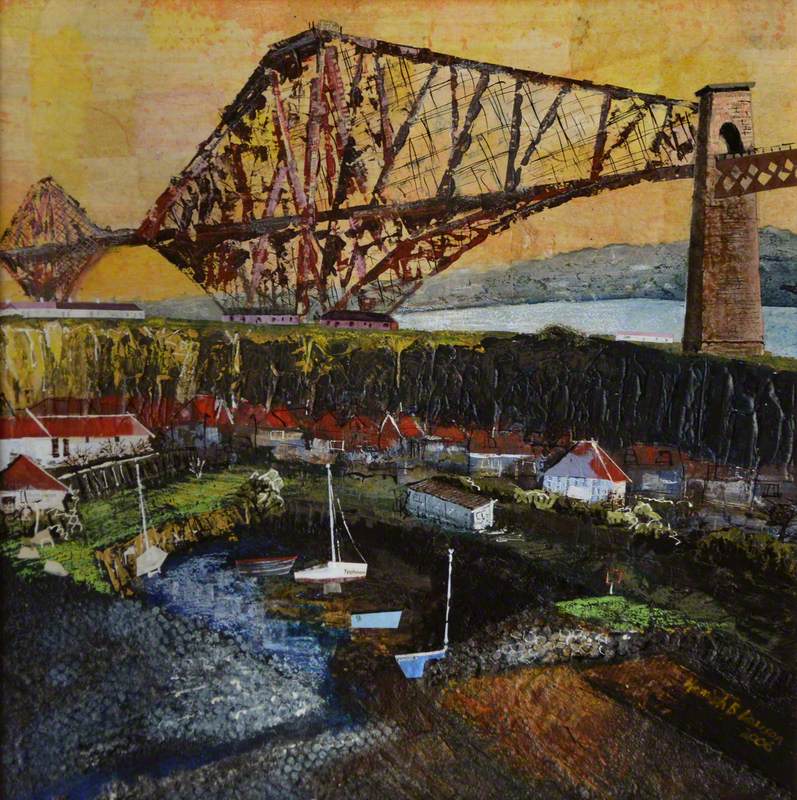

Throughout the grim years of the First World War, Hunter worked on his cousin Robert's farm in Lanarkshire, but in 1919 he started afresh in Fife on the east coast of Scotland, enthusiastically writing to a friend that he was concerned entirely with the animation of the landscape.

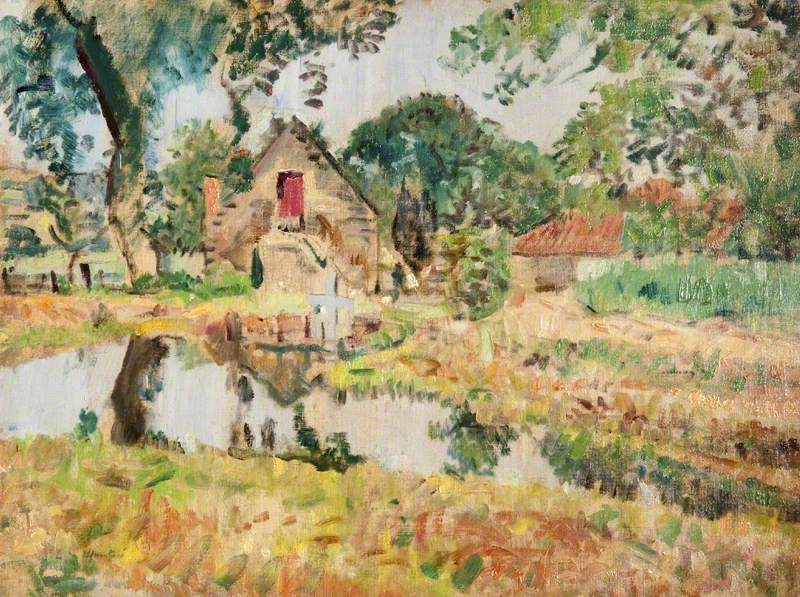

From early days in San Francisco, Hunter took to heart the view of German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1780–1860) that colour is the sensation in the eye, rather than the actual colour of an object. Old Mill, Fifeshire, with its bold colour, texture and harmonious design that places you in the landscape, brilliantly demonstrates Hunter's new-found confidence.

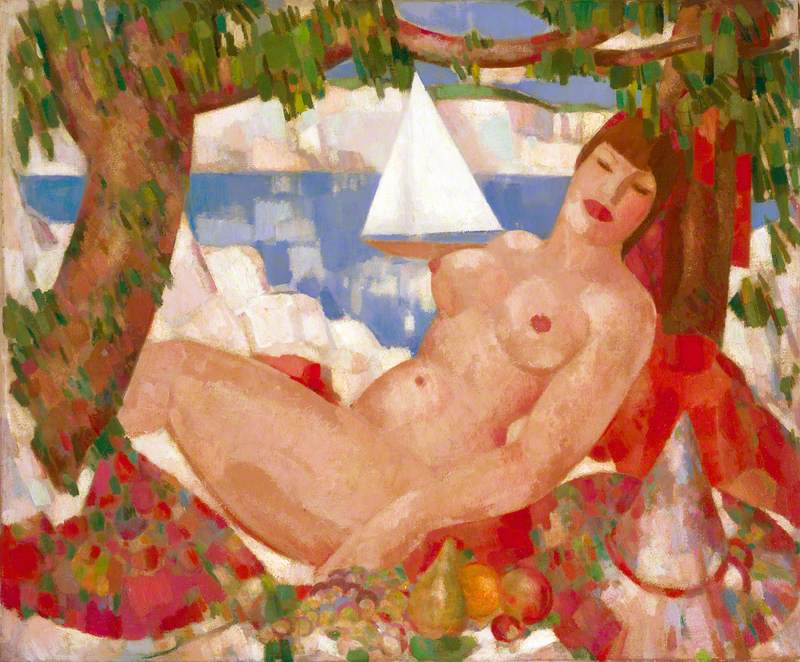

In still life, he developed new colour sensations to create form, then choosing an onion or whatever was to hand as a basis to paint an orange or apple from his imagination, he focused on painting the 'weight' in fruit, not an accurate visual object.

Roses, a Melon and a Japanese Print

c.1918

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

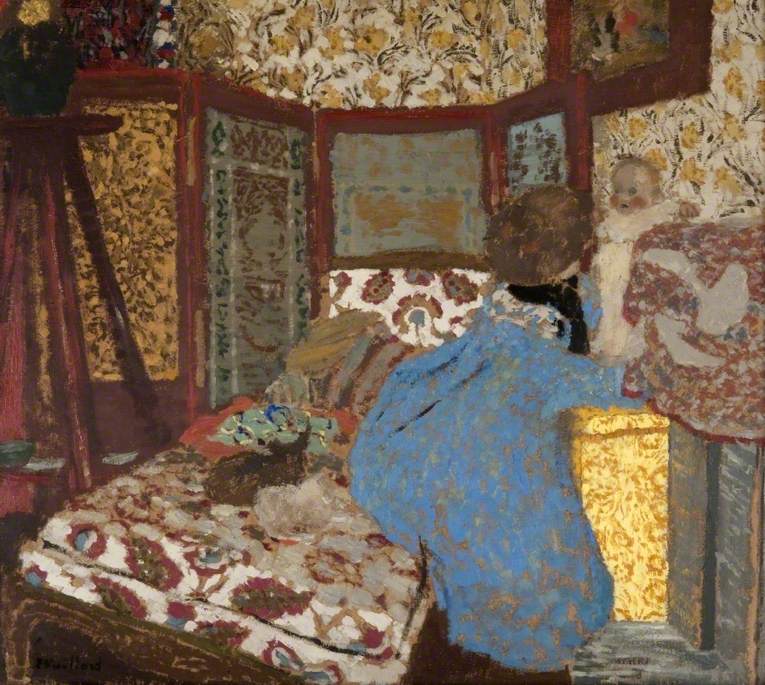

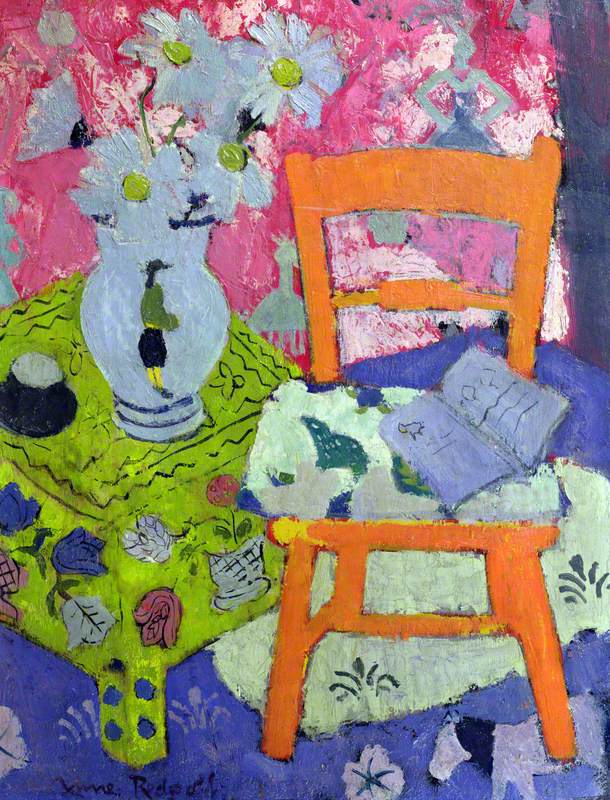

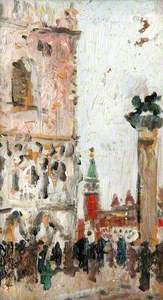

Fresh from subsequent exhibition sales, Hunter travelled to Italy in 1922. Painting outdoors, he dared to reinvent the sense of pattern and vitality he'd been struck by in a series of intimate interior pictures by Post-Impressionist Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940) that a friend owned.

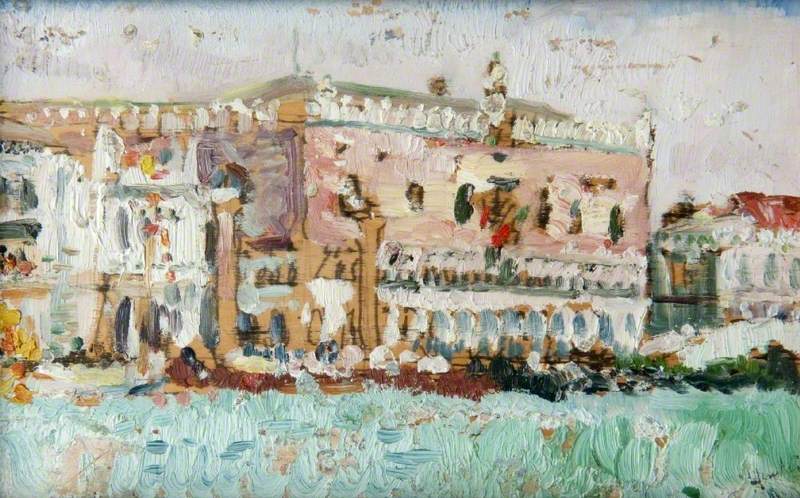

Hunter blended subjects into colours and patterns that are deliberately flattened and decorative in The Doge's Palace and Souvenir de Venise.

On his return to Fife, he pressed on to produce stunning landscapes in vibrant colours.

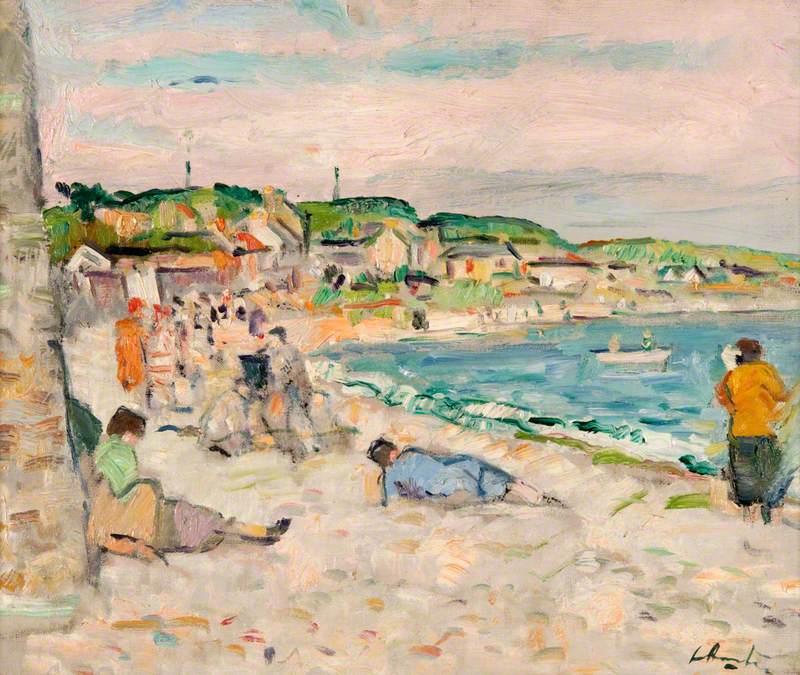

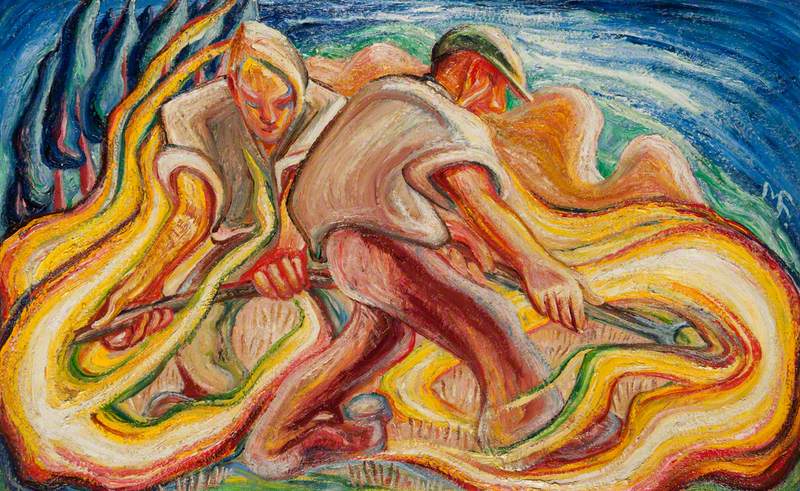

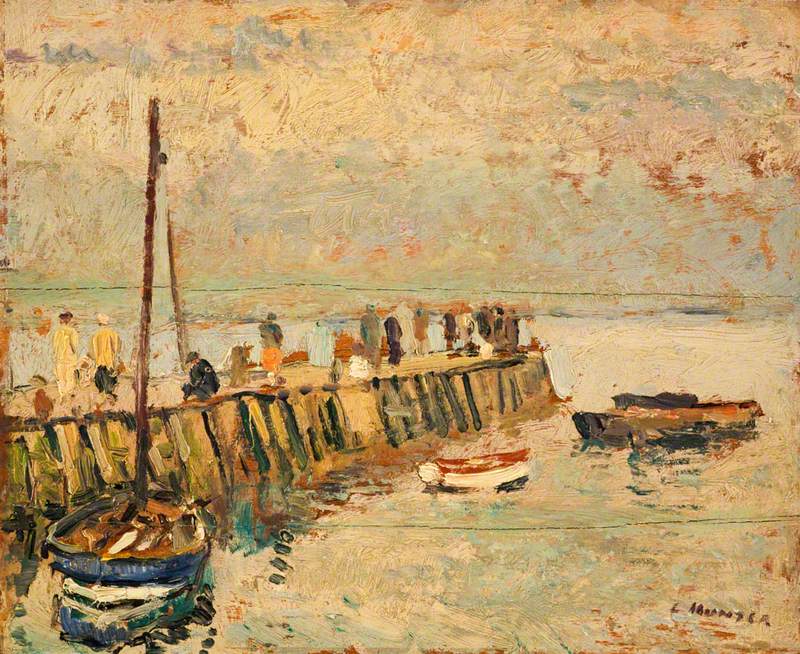

Likewise in Figures on a Quay, Largo and Largo Beach, he assembled figures as areas of colour that play into the joyous pattern of the scene in front of him.

Figures on a Quay, Largo

c.1920–1925

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

Later in the year in his Glasgow studio, his still life brims with colour, vitality and design.

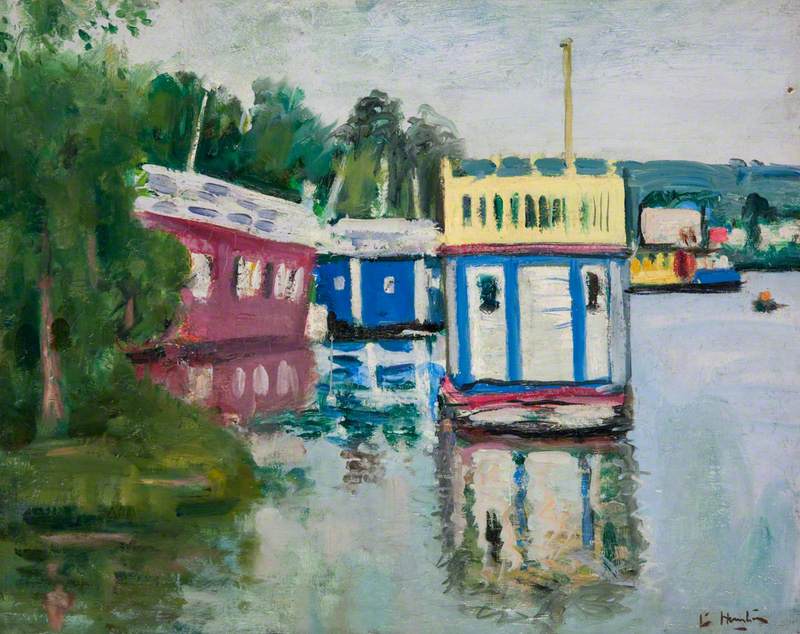

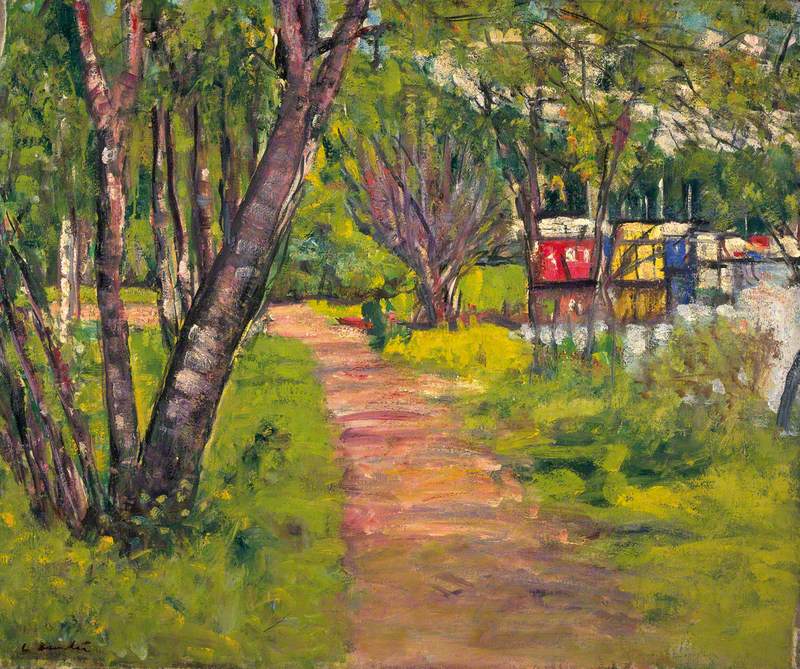

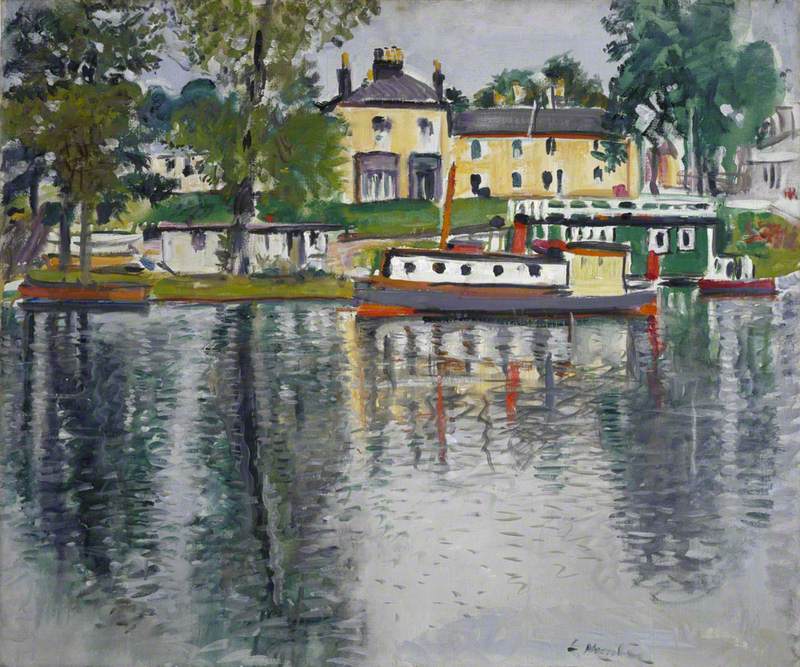

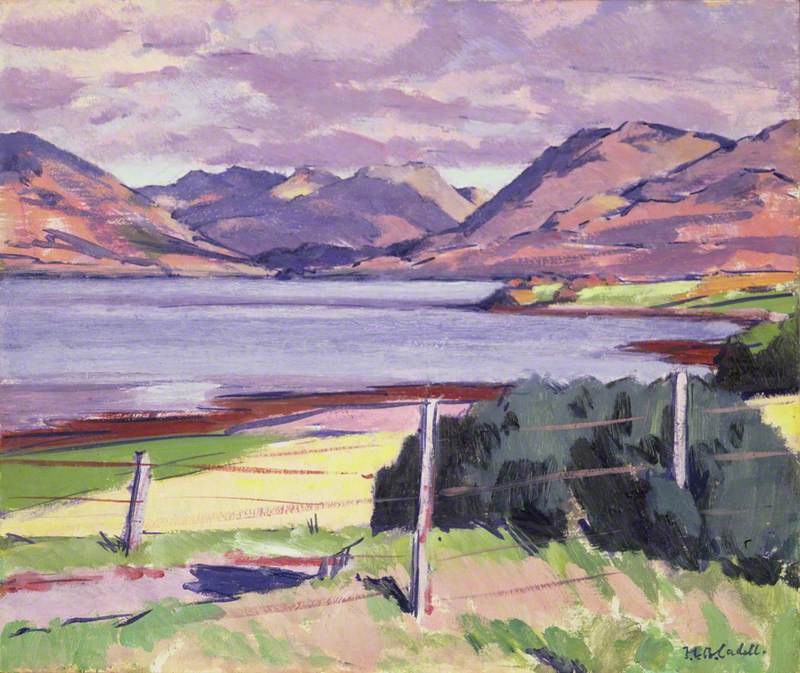

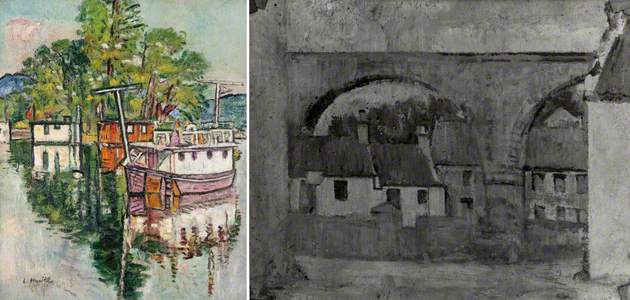

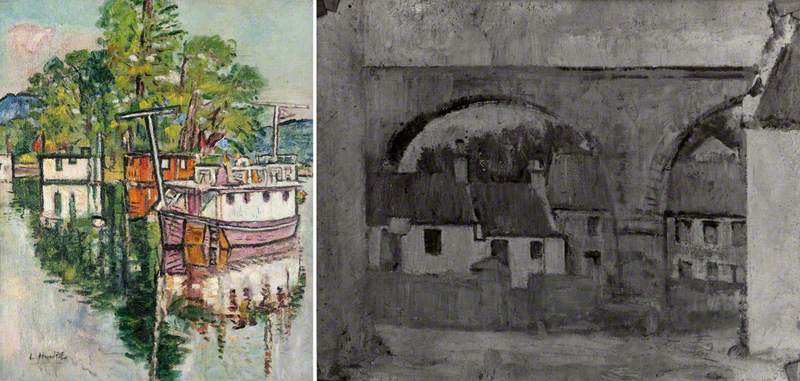

In 1924, Hunter found new inspiration among the houseboats moored on Loch Lomond, which served as a fashionable weekend retreat for city-dwellers from Glasgow. Energised by Matisse's new work in Paris, Hunter exercised a bold simplification of colour and perspective, encouraging his art dealers to sign a three-year contract with him.

House Boats at Balloch (recto), Cottages under a Railway Bridge (verso)

c.1924

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

It is from this first series of houseboats that the French government purchased a painting in 1931. With typical humour, Hunter commented to Honeyman, 'What about prophets without honour?'

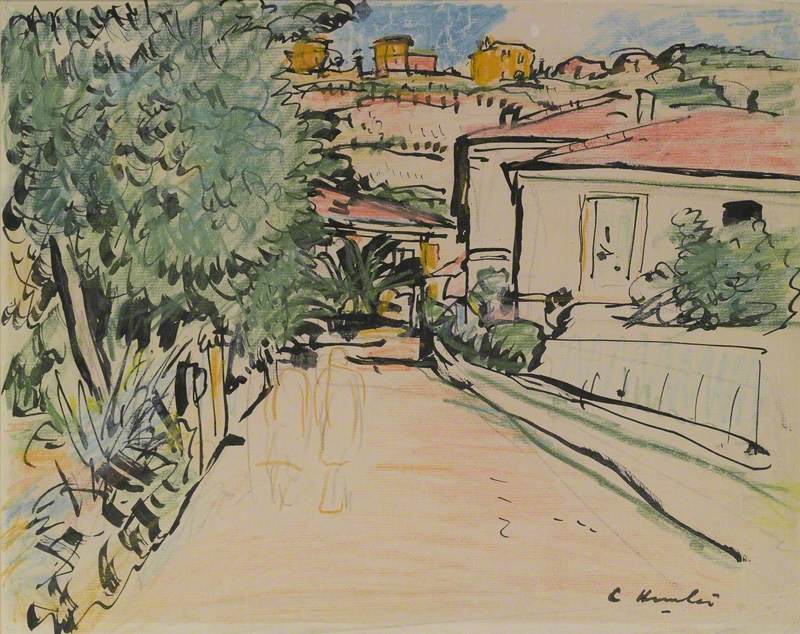

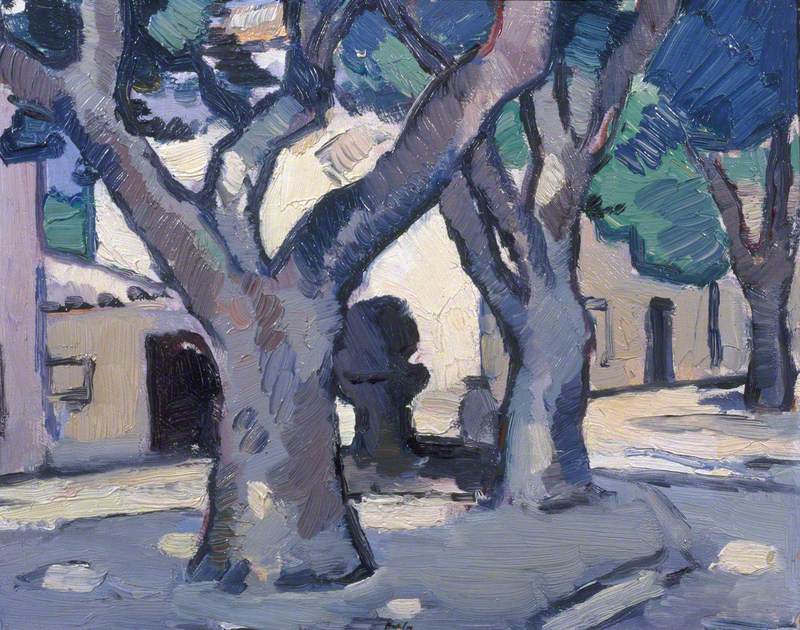

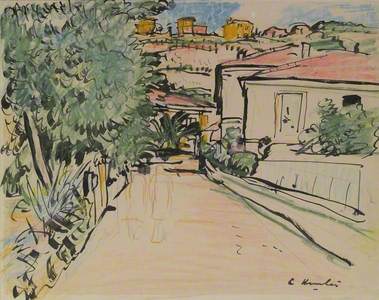

In 1927, Hunter abandoned Scotland's changeable weather for Provence in the south of France. On arrival, he wrote to a friend, 'This is a painter's country.'

Bright colour from his days in California was with him from the beginning, and his Fife paintings sang with colour and form before he even reached the Cote d'Azur, but seduced by its irresistible qualities, he produced some of the finest paintings of his career. With the exception of Villefranche and Le Chemin du Mas, it appears surprisingly few works exist in public collections.

In 1929 Hunter pulled off a visit to New York and an exciting solo exhibition at the prestigious Ferargil Galleries. Shortly after returning to Provence, he fell gravely ill, necessitating an immediate return to Glasgow.

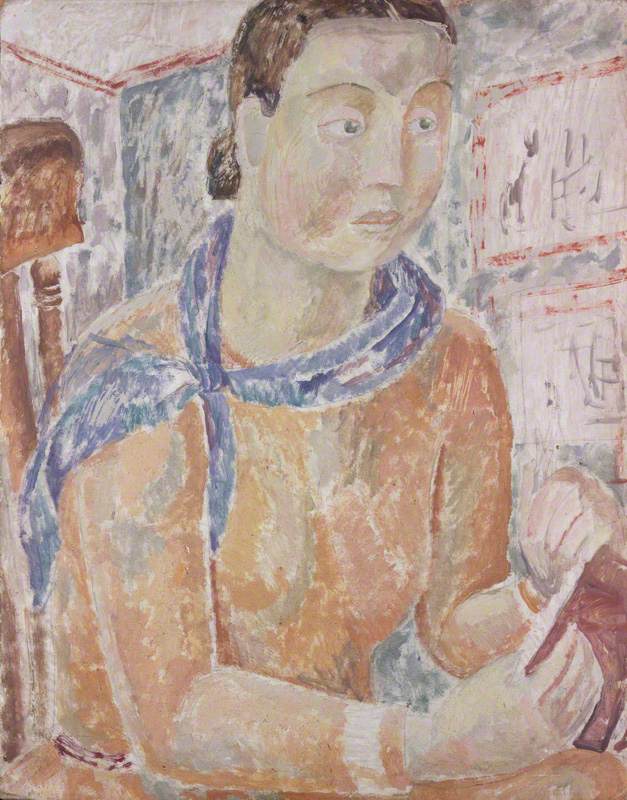

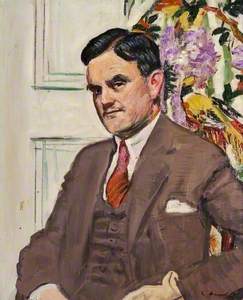

In what became his final two years of his life, Hunter's still life painting reached new heights, as did an exhibition of portraits that caused controversy among critics on whether an artist's style trumped a realistic representation of the sitter.

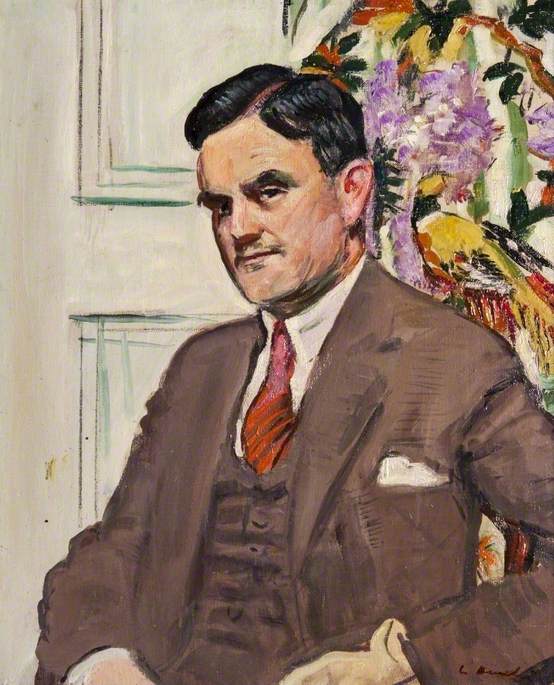

Dr Tom J. Honeyman (1891–1971), Director of Glasgow Art Galleries (1939–1954)

c.1930

George Leslie Hunter (1877–1931)

He spent the summer of 1930 living happily on a houseboat at Loch Lomond, where he painted one of his best-loved masterpieces, Reflections, Balloch. Sadly, a year and a half later, he died suddenly, the first of the Colourists to go. He was only 54.

Throughout his life, Hunter painted independently of Peploe, Fergusson and Cadell and each achieved greatness in their own right. When Peploe said of the 1924 houseboats painting that the French government acquired, 'That is Hunter at his best and it is as fine as any Matisse', he doesn't mean as in homage, he means as his equal – a truly brilliant Colourist.

Jill Marriner, art historian and co-author of Hunter Revisited: The Life and Art of Leslie Hunter

Further reading

Bill Smith and Jill Marriner, Hunter Revisited: The Life and Art of Leslie Hunter, Atelier Books, 2012

Palin on Art: The Bright Side of Life, directed by Eleanor Yule, BBC DVD, 2008

T. J. Honeyman, Introducing Leslie Hunter, Faber & Faber Ltd, 1937

T. J. Honeyman, Three Scottish Colourists – Peploe, Hunter, Cadell, Thos. Nelson & Sons, 1950

Janet Bishop and others, The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso and the Parisian Avant-Garde, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art & Yale University Press, 2011