Gareth Griffith grew up in Caernarfon, in North Wales, and has lived a short distance from there in Mynydd Llandygai, near Bangor, for over 40 years. He studied at Liverpool College of Art in the early 1960s and spent the majority of his working life as an art teacher. Following his retirement, he built a new studio space in his garden and has been producing some of the best work of his career since. He is represented in the collections of Amgueddfa Cymru, Walker Art Gallery and the Arts Council Collection and was joint winner of the 2022 BEEP Painting Biennial in Swansea.

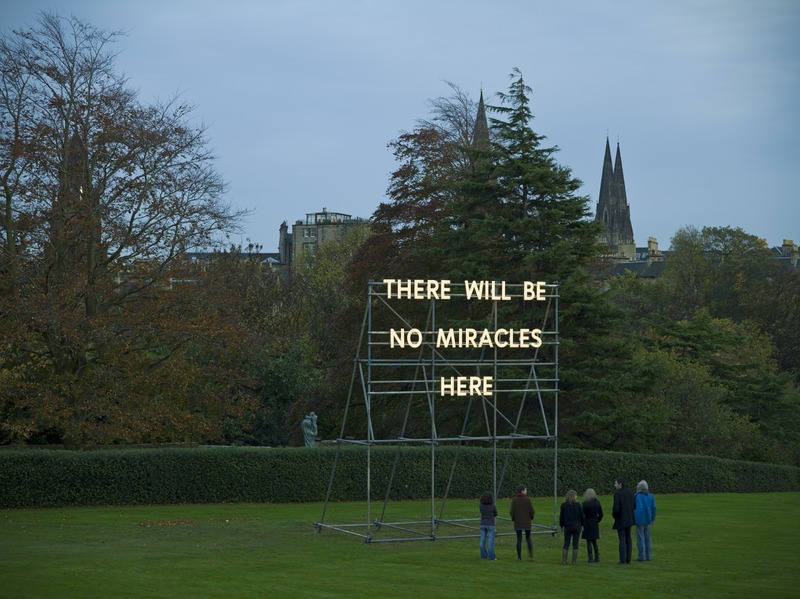

He has staged numerous exhibitions across Wales in recent years, with the 2019 solo touring exhibition 'Trelar // Trailer' chief amongst these. Curated by Oriel Davies, the show toured to Aberystwyth Arts Centre, Tŷ Pawb and Oriel Myrddin and was a treasure trove of recent work – as close as you could get to being in Gareth's studio whilst in a gallery. In fact, calling it a touring exhibition does 'Trailer' a bit of a disservice, as in reality, it changed dramatically at each venue – so it was more like four completely distinct exhibitions. The show was a work in and of itself, with Gareth collaborating with curator Steffan Jones-Hughes to construct it anew for each venue.

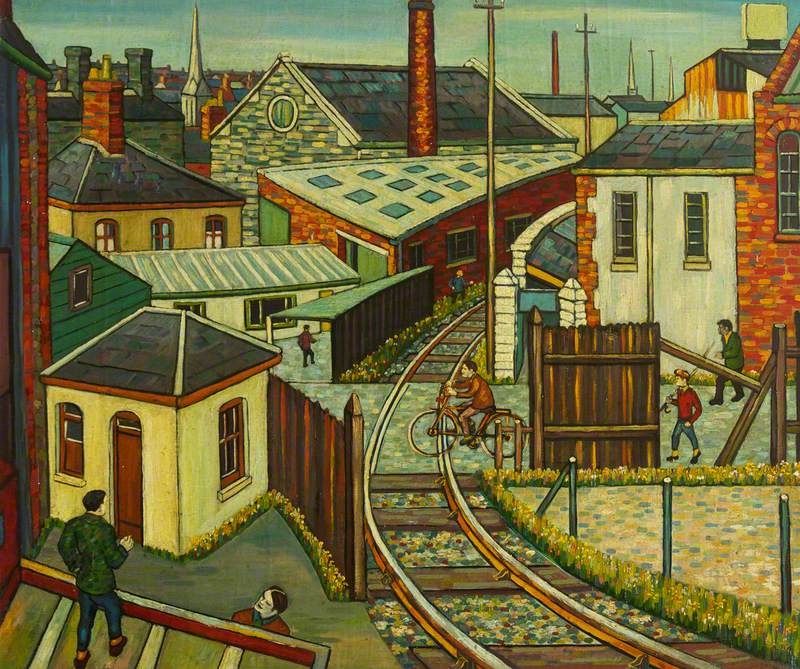

'Trelar // Trailer' exhibition at Oriel Davies

2020, multimedia by Gareth Griffith (b.1940)

This says a great deal about Gareth as a creative force. He is one of the most extraordinary artists working in Wales today and produces work that is wildly creative, light-hearted, shocking and fiercely intelligent. It has a visual language of its own and Gareth works in a non-linear way: works do not so much as begin and end, but drift in and out of his orbit. There are layers of reference and astute historical, social and political knowledge.

His work is also deeply personal, recalling events and incorporating real objects from his life. Some of these episodes, like the recurring references to his time living and working in Jamaica in the early 1970s, where he was very nearly murdered, are incredibly shocking.

With that said, it is almost pointless to try to pin down or classify Gareth's work too much as it does no justice to its freewheeling brilliance. Yes, there are drawings, paintings, sculptures, found objects, the ready-made, and cultural references to art, music and literature. Imagine all of this but at the same time, and in series that aren't particularly chronological, where works are often repurposed and reworked back into something new.

View this post on Instagram

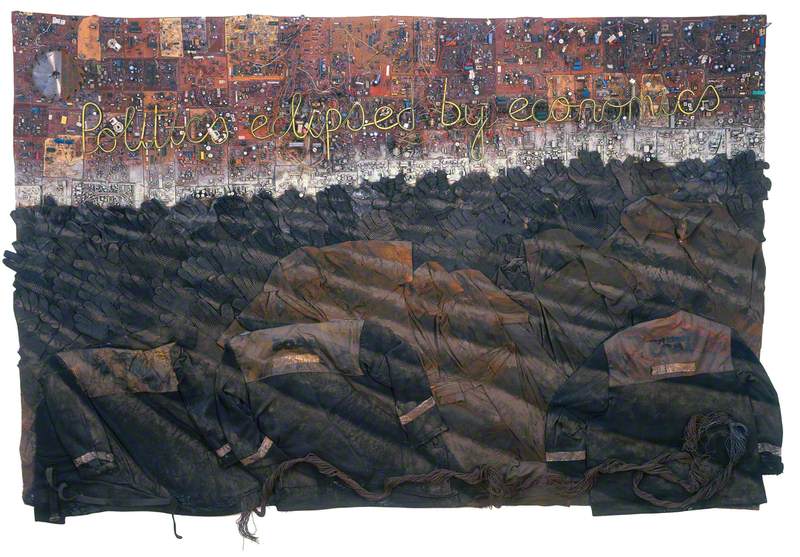

Bertorelli (2019) is a perfect example. A major work from the 'Trailer' exhibitions, it is now part of the collection at National Museum Cardiff. On first encountering it at Oriel Davies, I had the sensation of knowing that it was a work of complete brilliance, but without being able to articulate exactly why.

It is a visual feast for sure: a central painting seemingly spills out onto the gallery walls with three-dimensional versions of what is shown on canvas. Objects appear apparently at random, yet subtly mirror each other, and have colour and formal relationships that subconsciously make sense. There are flashes of yellow throughout that give it coherence and that pop against the muted grey of the background (more on that later).

But this is not just an experiment in abstraction – Bertorelli is a work very close to home for the artist. The Bertorellis were an Italian family who owned an ice cream parlour in Caernarfon, and where Gareth frequented as a child in the 1950s. The 'real' portrait at the bottom of the work hung in the Bertorelli's ice cream parlour and Gareth came across it decades later in a house clearance. He added his own interventions to the painting thereby creating the seed for what eventually became the finished piece.

I often think of Gareth's work in terms of a musician improvising around a melody. It's all anchored in the theoretical building blocks – history, form, dimension, colour, spatial relationships – but they are all tested, deconstructed and rebuilt. Bertorelli is the product of an artist at the top of their game: ambitious, confident, poignant and experimental.

Synagogue, from the 'Mirror of Human Salvation' altarpiece, outer side

c.1435, mixed media on oak wood covered with canvas by Konrad Witz (1400–1445/1447)

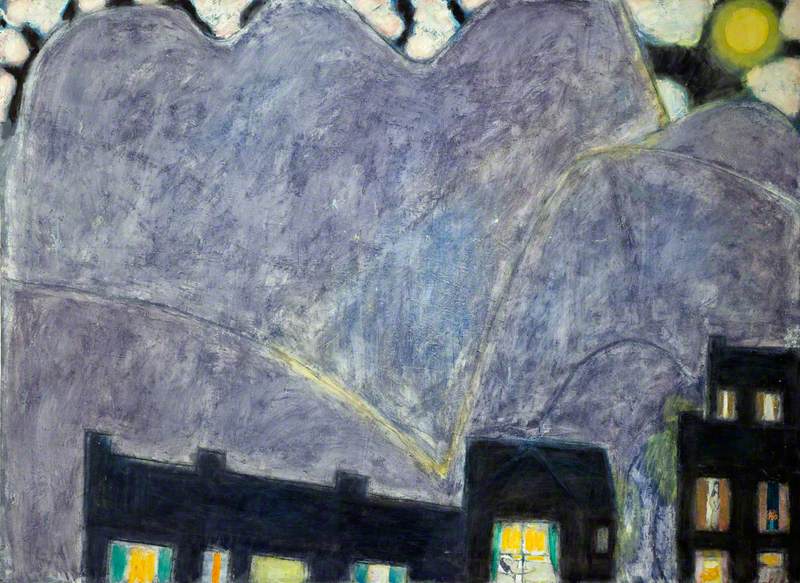

Gareth has pointed to a formative moment in his 20s that helped shape his creative outlook. Whilst at art college in 1962, he was shown a copy of Johannes Itten's seminal book The Art of Colour (1961). This explores colour relationships, theory and uses of colour in art throughout the centuries. Among the paintings referenced is Konrad Witz's Synagoga (The Synagogue) from the mid-1430s. A little-known but no less important Swiss painter of the late Gothic period, very few of Witz's works survive. Only one painting, by a follower of Witz, exists in a public collection in the UK.

Itten includes the Witz painting in The Art of Colour because of the astonishing use of yellow in the dress of the main figure, made all the bolder by the grey and claustrophobic background she is contained within. The symbolism of that yellow is debated; Itten ascribes its use to 'the rational, logical thought and philosophical learning of the Jews' whilst art historian Ruth Mellinkoff argues that the yellow – and the depiction of the allegorical figure Synagoga in religious paintings of the era more generally – had the opposite intent in Medieval Europe.

What is certain is the impact that Witz’s painting had on Gareth Griffth, the art student, during the 1960s: 'it's the image I always turn to, the yellow figure trapped in a small space.' Gareth has used this work as the basis for a series of sculptures, drawings and paintings that look to Witz's work as a touchstone. When I visited his studio a few years ago, there was a group of 'Konrad' works displayed together and the varying degrees of abstraction of the figure were all held together by that buttercup yellow.

If Witz's fifteenth-century original brought to mind confinement, then, with Walking Konrad (2012) from the Arts Council collection, Gareth is releasing the figure and it strides out of the enclosed space. A remnant of a yellow plastic container stands in for the dress, seemingly blowing in a breeze. The plastic, which is mirrored in many works from the Konrad series, inevitably brings to mind waste and pollution, and the luminous yellow of brightness and hope but also warning.

Possibly. But then again, possibly not.

What is fascinating about Gareth's work is that you are encouraged to come to it on your own terms and take away from it whatever you like. While there are strata of reference, and the knowledge and experience of over 80 years of life, his work has ultimately generous intentions. There is no prescriptive reading, nor does he set out with one himself. Gareth is often discovering the work almost as we are discovering it.

He summed this up in an interview for his 2022 exhibition at Storiel in Bangor: 'This is about my life and experiences. What has happened to me. What I've experienced. What else is there? I hope there are no easy conclusions to be made.'

Neil Lebeter, curator and writer

This content has been supported by Welsh Government funding

Gareth Griffith will feature in the Beep Painting 2022 winners' exhibition at Elysium Gallery, Swansea from 19th July to 14th September 2024

Further reading

Neil Lebeter, 'Gareth Griffith: Artist's Room', Celf ar y Cyd – Cynfas, 2024