In recent months, public statues have become a symbolic battleground for our understanding of race and history. As Black Lives Matter protests have called for a rethinking of who we honour in public art, opposition groups have gathered, claiming to 'protect' war memorials.

However, the idea that BLM protesters would damage war memorials erases the sacrifices made by black and brown people from across the British Empire in wartime. In fact, the movements for civil rights and independence born in part from the frustration of World War veterans across the Empire are echoed in the spirit of the contemporary BLM movement.

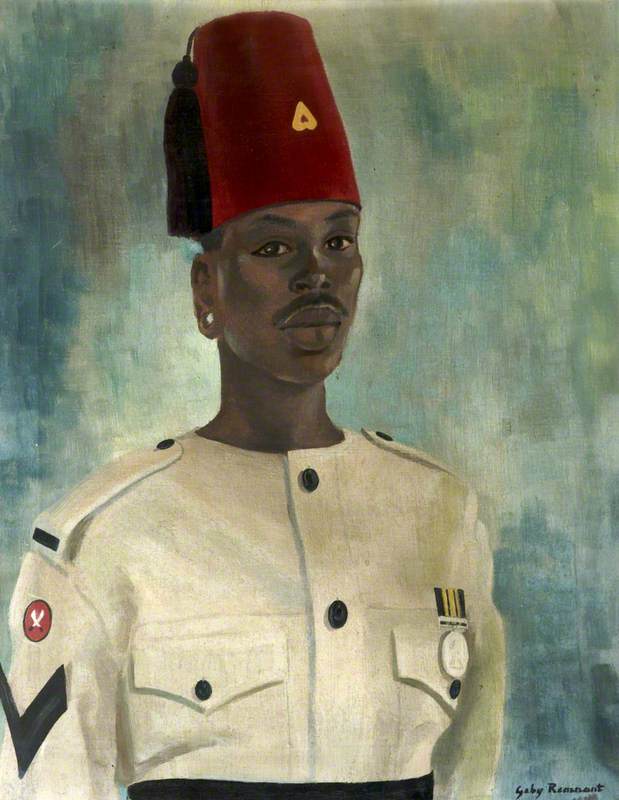

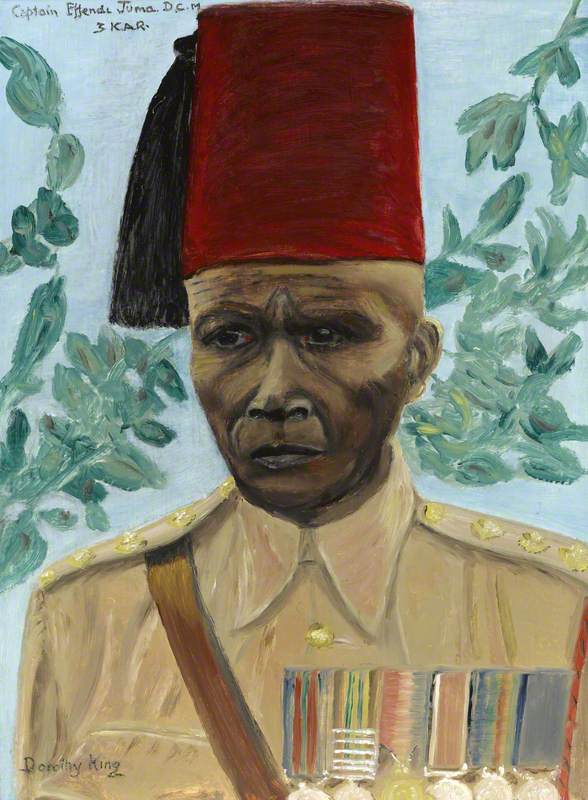

The nation's public art collections hold a few precious records of the Empire's diverse army. Contemporary artist Barbara Walker (b.1964) began researching this history while working on a project on contemporary conflicts.

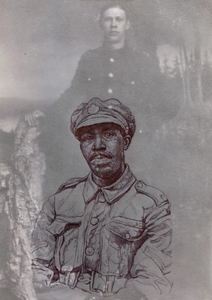

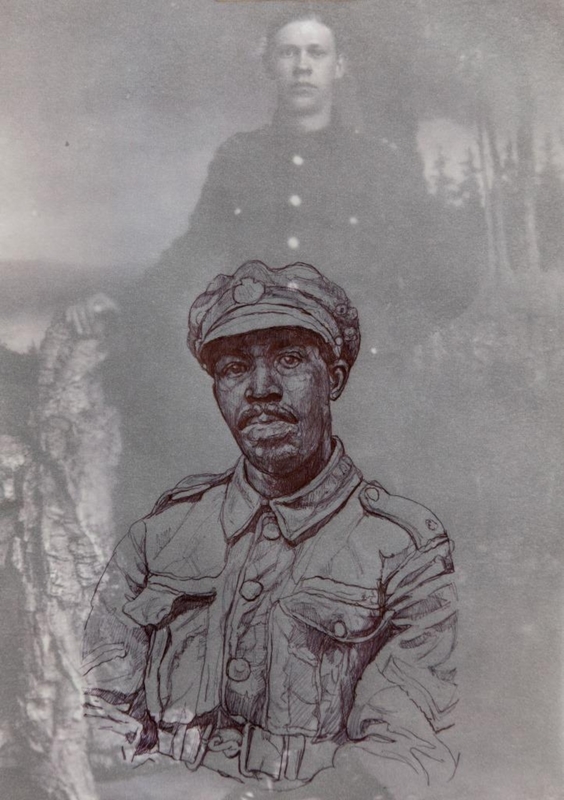

I Was There IV confronts the erasure of black soldiers by reinserting their presence through a pen and ink drawing which is laid over an archival image of a white soldier. By using tracing paper Walker ensures the white soldier is still visible while reinserting the black soldier into the image, demonstrating that the re-examining of history is not an erasure of stories we already know.

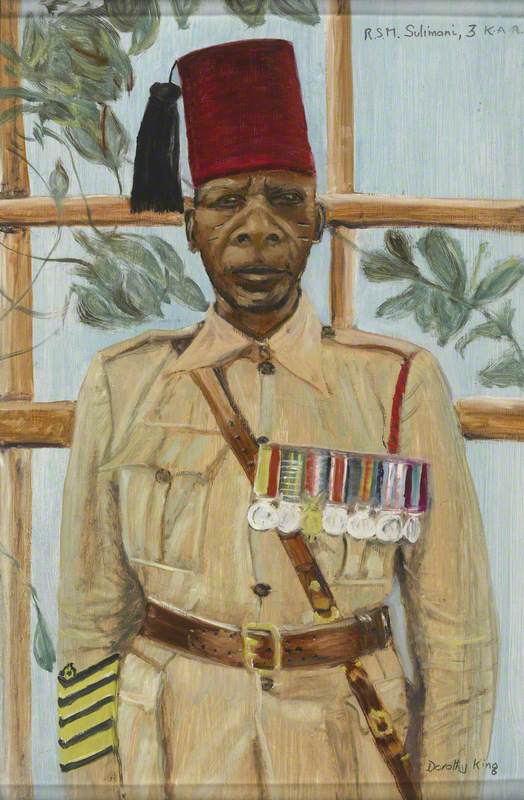

Walker's black soldier is unnamed. He may have been one of 15,000 Caribbean men from islands colonised by Britain who served with the West India Regiment or the British West Indies Regiment during the First World War. At the start of the war, these men were given labouring jobs and were not allowed to fight alongside white soldiers until 1916. Walker's soldier may well have been from one of the African countries within the Empire; if so he might have served with the West African Frontier Force or the King's African Rifles.

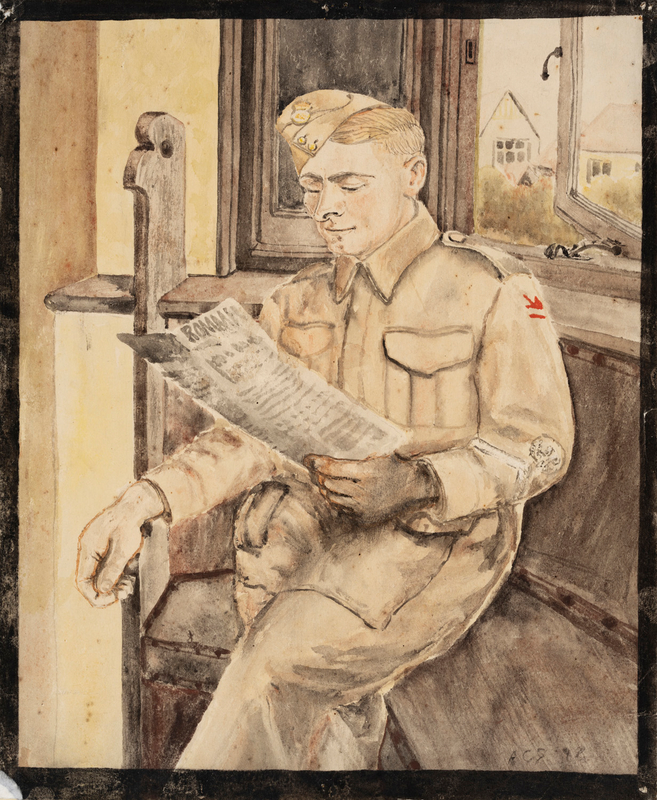

Had he served in the Second World War he might have been of the 5,500 Caribbean RAF personnel, who were also joined by Caribbean women, with 80 of them within the Women's Auxiliary Air Force and 30 within the Auxiliary Territorial Service. This unnamed soldier becomes a symbol for all these individuals, whose stories often go untold or are forgotten.

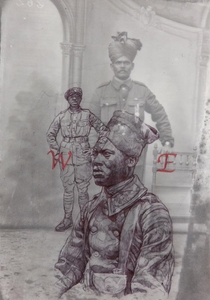

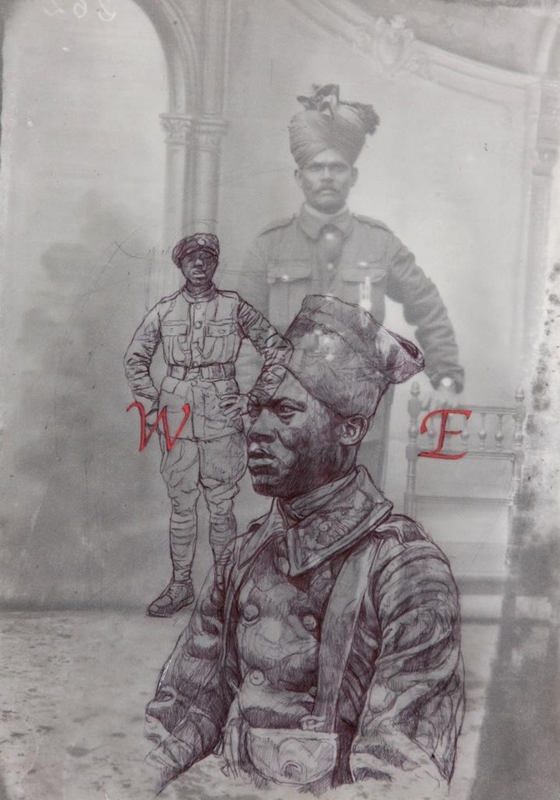

Alongside drawings of black soldiers, I Was There V features an archival photograph of an Indian soldier. During the First World War, over one and a half million soldiers from the Indian sub-continent served alongside British troops. These soldiers came from a range of countries, including India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and practised various religions, including Sikhism, Hinduism and Islam.

The struggle between the Empire and those it colonised is also alluded to in I Was There V, with two red letters W and E representing the familiar dichotomy of West and East, which the wars broke down.

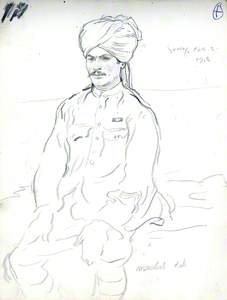

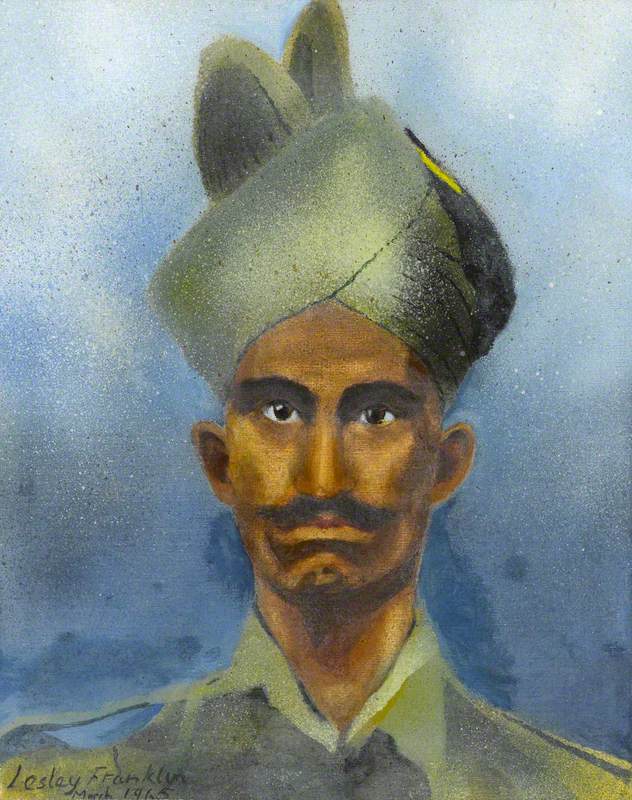

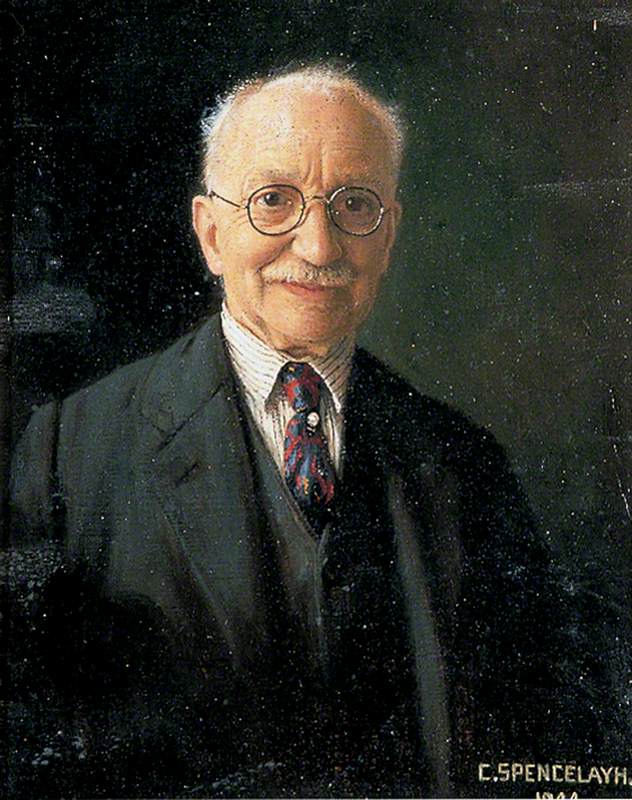

While Walker uses archives to connect to these men, war artists like Alfred Munnings (1878–1959) captured portraits of them on the Western Front.

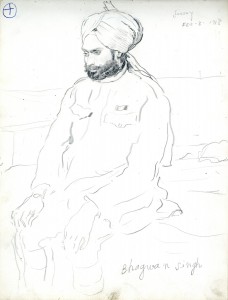

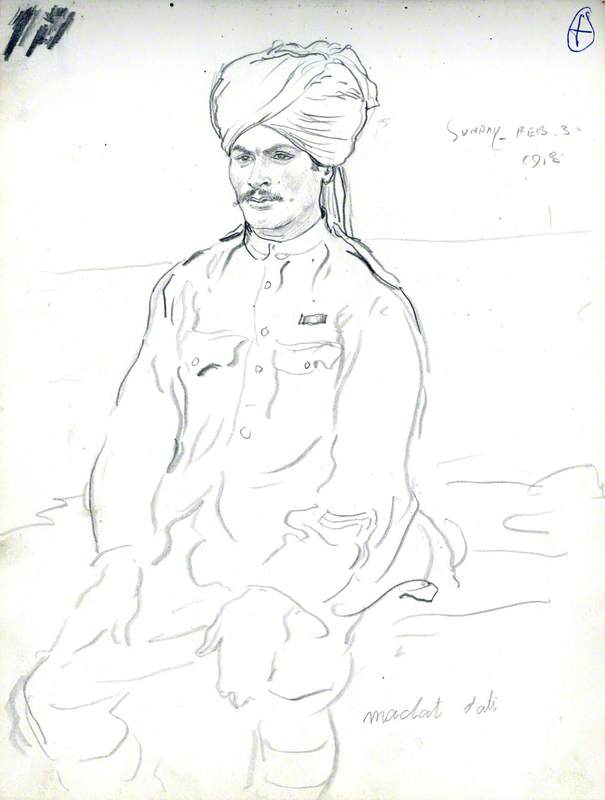

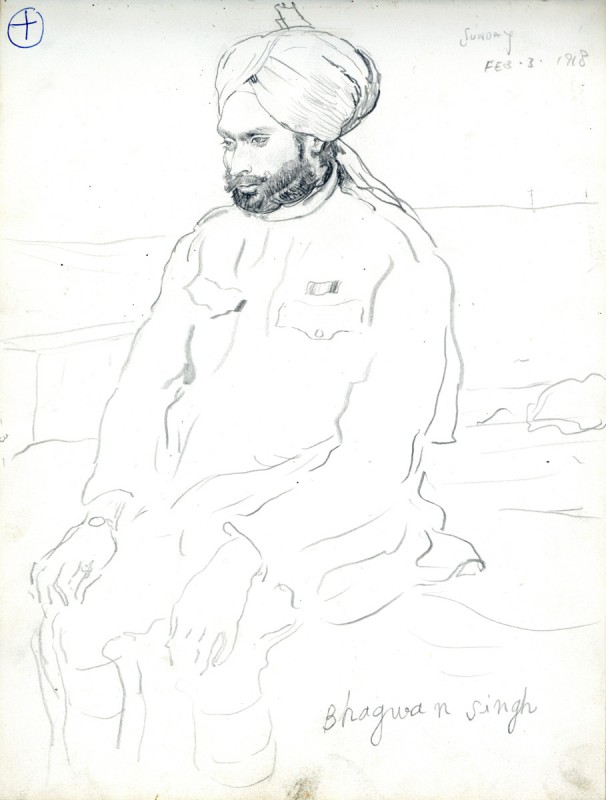

In February 1918, while Munnings was embedded with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, he sketched two Indian soldiers.

We know from Munnings' notes that the two soldiers he met were called Madat Ali and Bhagwan Singh. It appears Munnings did not have much time to make these sketches, as only their faces are fully fleshed out, but what is there is an important record of the individuals who formed part of the Indian regiment on the front lines of the war.

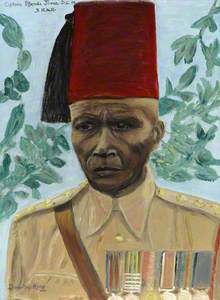

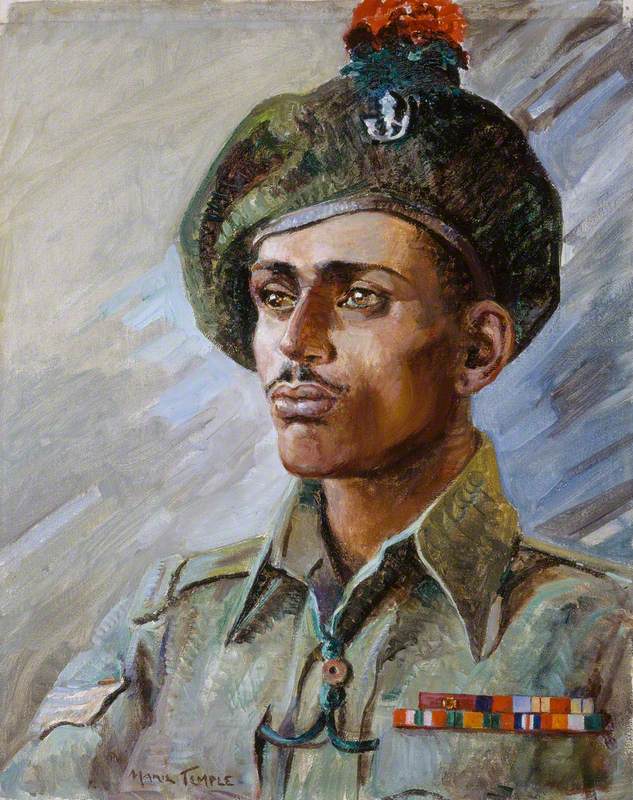

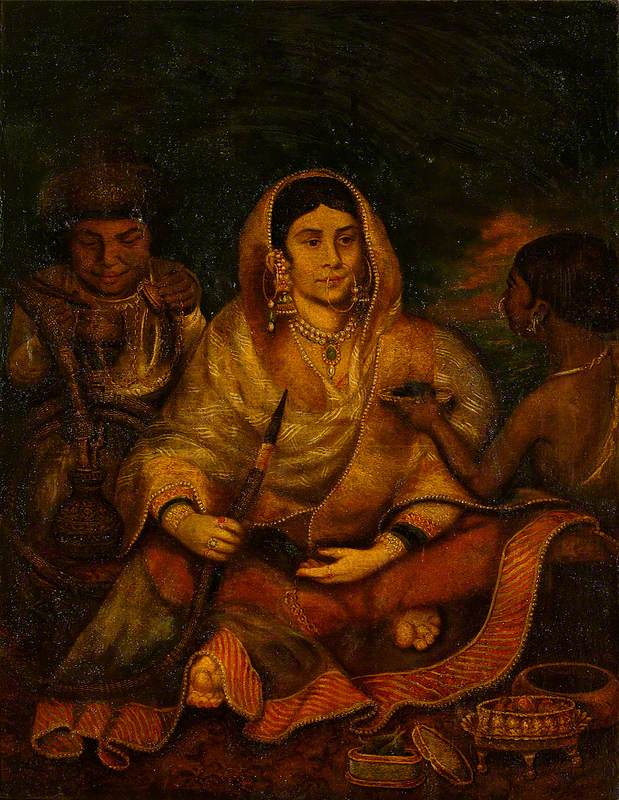

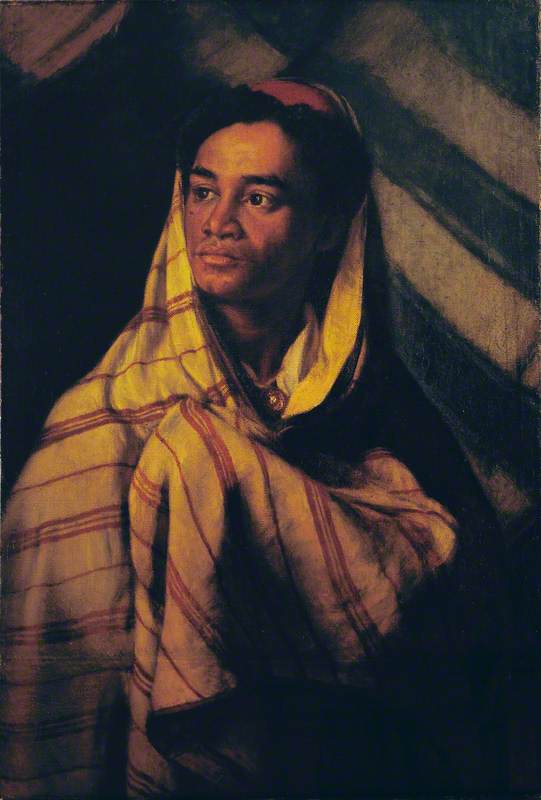

Little more is known about Ali and Singh, but there is a painting by Henry Charles Bevan-Petman which tells us more about the experiences of a soldier from the Indian subcontinent. This is a portrait of Khudadad Khan (1888–1971), who was the first Indian soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross in 1915 for his actions on 31st October 1914.

Subadar Khudadad Khan (1888–1971), VC, 10th Baluch Regiment

1952

Henry Charles Bevan-Petman (1894–1980)

Despite being wounded, Khan remained to man his gun and held off the opposing forces just long enough for reinforcements to arrive. It is this extraordinary act of bravery that would have made Khan an appropriate subject for a portrait, which becomes an important record of his story.

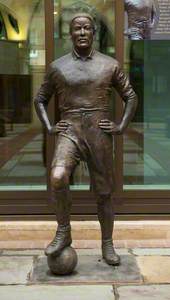

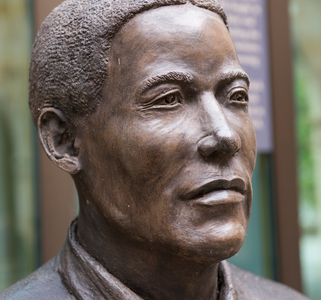

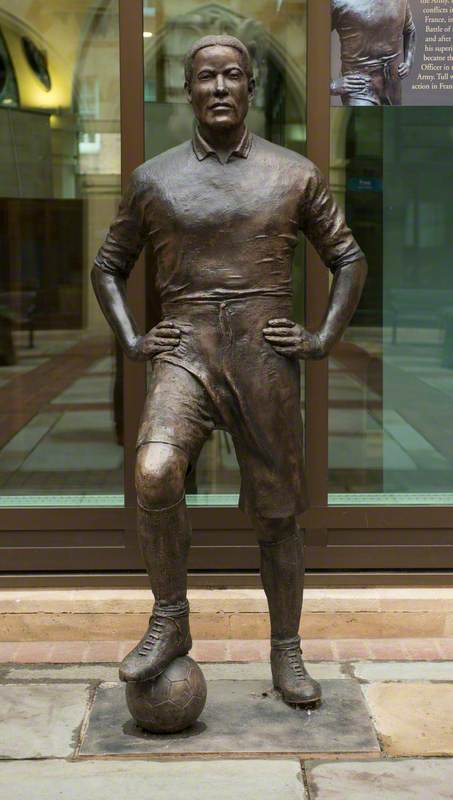

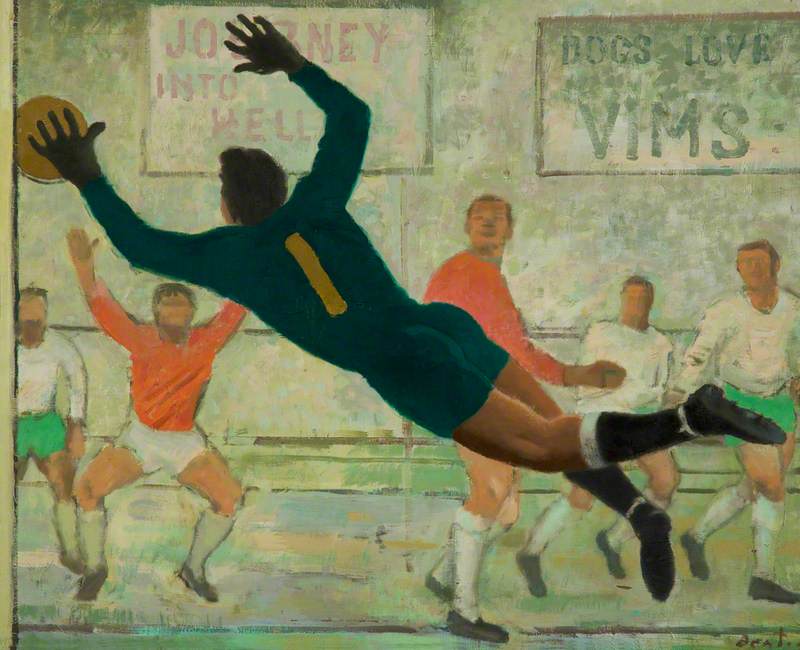

Not all of the black and brown soldiers who fought during the First World War were born outside Britain. Walter Tull (1883–1918) was born in Folkestone, Kent, like his mother Alice. His father Daniel had emigrated from Barbados to England. Tull became a footballer, playing for Tottenham Hotspur and Northampton Town.

During the First World War, he joined the Football Battalion where he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant and became the first black officer in the British army. He was killed crossing No Man's Land on 25th March 1918.

Richard Austin's sculpture of Tull in his football kit was installed outside the Northampton Guildhall in 2017. Representing Tull in his football kit reminds us of the rich lives those who fought in the World Wars lived, many of which were cut short.

Tull's ability to rise through the ranks was exceptional and impossible for most black soldiers due to colour bars. Outside of the armed forces, racial discrimination was felt by those who settled in Britain post-war and for those who returned to their countries of origin. There was frustration that despite their sacrifices they remained under British rule, leading for renewed calls for independence across the Empire.

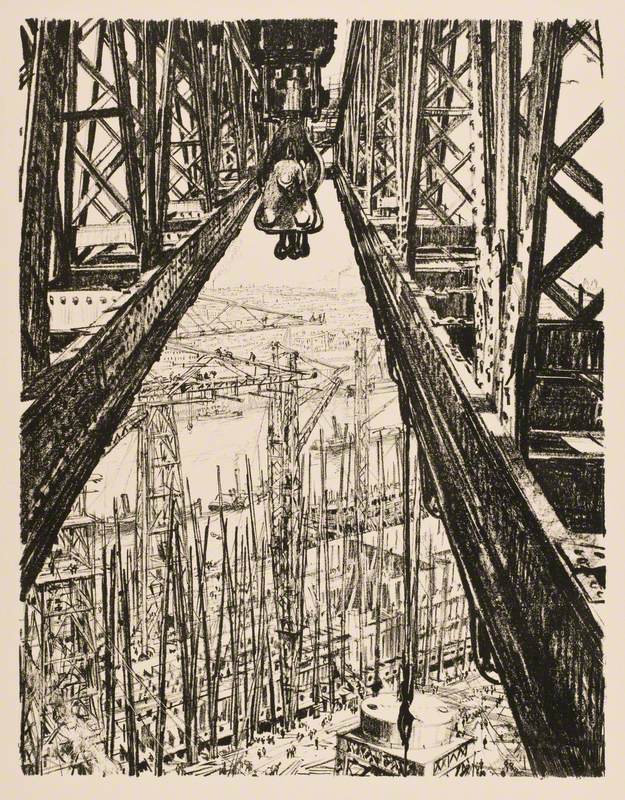

Alongside artworks of the servicemen and women, there are public memorials across the country which commemorate soldiers from the Empire. In Brighton, the Chattri Monument commemorates the 12,000 Indian soldiers who were wounded on the Western Front and hospitalised at sites around Brighton.

It is located on the site where 53 Hindu and Sikh soldiers who died in hospitals in Brighton were cremated. Funeral ceremonies were carried out by fellow soldiers who conducted traditional prayers while cremating and scattering the ashes of their comrades.

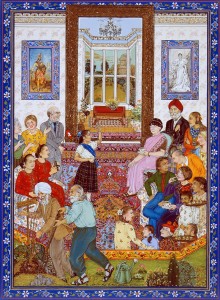

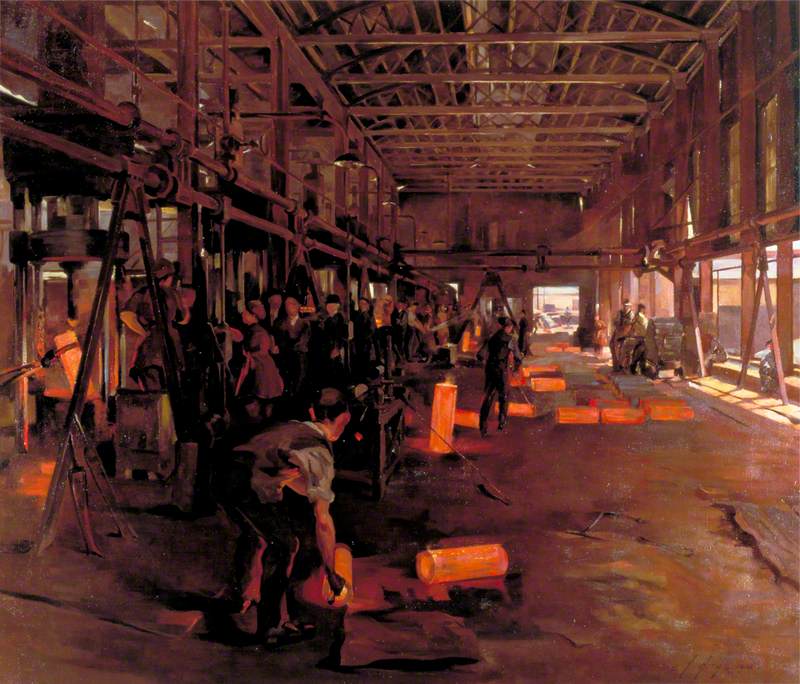

Music Room of the Royal Pavilion as a Hospital for Indian Soldiers

1915

Charles Henry Harrison Burleigh (1869–1956)

In London, Hyde Park's Commonwealth Memorial Gates were unveiled in 2002 to commemorate the armed forces of the British Empire who served in the two World Wars.

Commonwealth Memorial Gates, Constitution Hill

2002, designed by Liam O'Connor, built by Geoffrey Osborne Ltd and CWO Ltd (stonemasons)

In Windrush Square in Brixton, South London, the African and Caribbean War Memorial was unveiled in 2017.

African and Caribbean War Memorial, Brixton

designed by Jak Beula Dodd (b.1963)

All those who fought in the wars should be remembered for their bravery and sacrifice, but far too often the lives of those who came from across the British Empire are forgotten.

These artworks and memorials capture their stories. They help us to expand our understanding of race and Britishness, by allowing us to understand the history of racism, colonialism and Empire alongside that of sacrifice, independence and diaspora.

Chloe Austin, curator, art historian and art writer

Further reading

Brough Scott and Jonathan Black (eds.), Alfred Munnings: memory, the war horse and the Canadians in 1918, London, 2019

Shrabani Basu, interview with Christopher Finnigan, 'The Story of 1.5 million soldiers that served in WW1 has been forgotten over the years', LSE, November 2018

'WW1 Pakistani VC recipient Khudadad Khan', case study published by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, June 2016

Phil Gregory, 'Caribbean Women in WWII' in Black Presence, February 2013

Lisa Peatfield, 'The Story of the British West Indies Regiment in the First World War', Imperial War Museum, June 2018

Rahil Sheikh, 'Forgotten Muslim soldiers of World War One 'silence' far right', BBC Asian Network, November 2018

'The Commonwealth and the First World War', National Army Museum

Richard Conway and David Lockwood, 'Walter Tull: The incredible story of a football pioneer and war hero', BBC Sport, March 2018

.jpg)