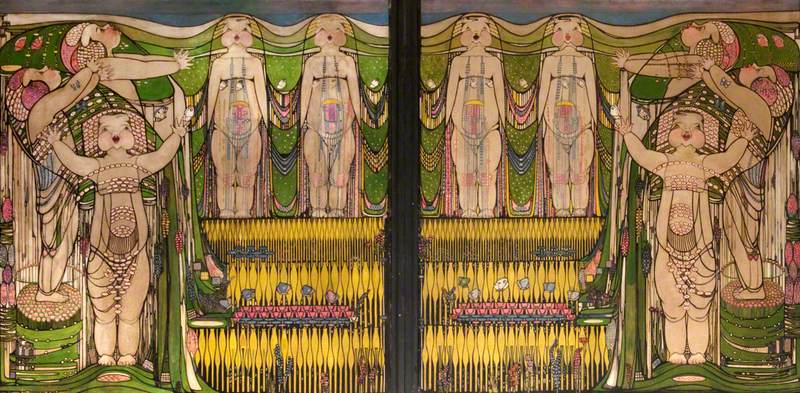

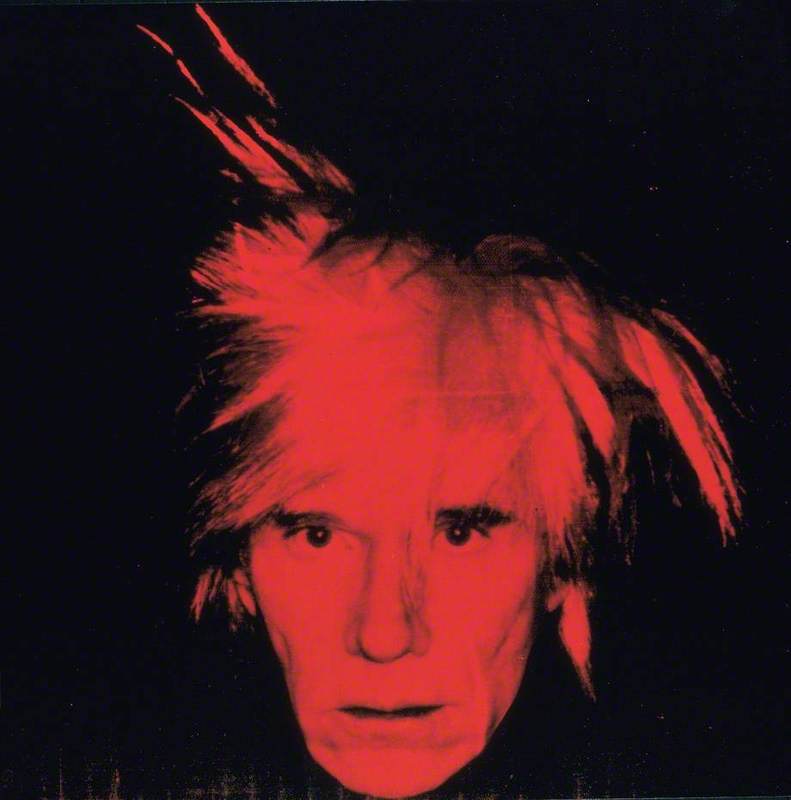

Those artists who bring change to the state of art tend to draw our interest when a period is looked back on, but there are always many others who are worth attending to if we wish to have a thorough understanding of a past era. This is very much the case with early twentieth-century British art, when the majority of artists were concerned with how to negotiate new trends rather than to prosecute them.

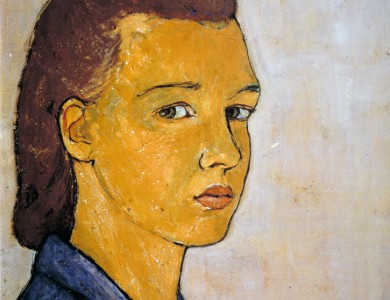

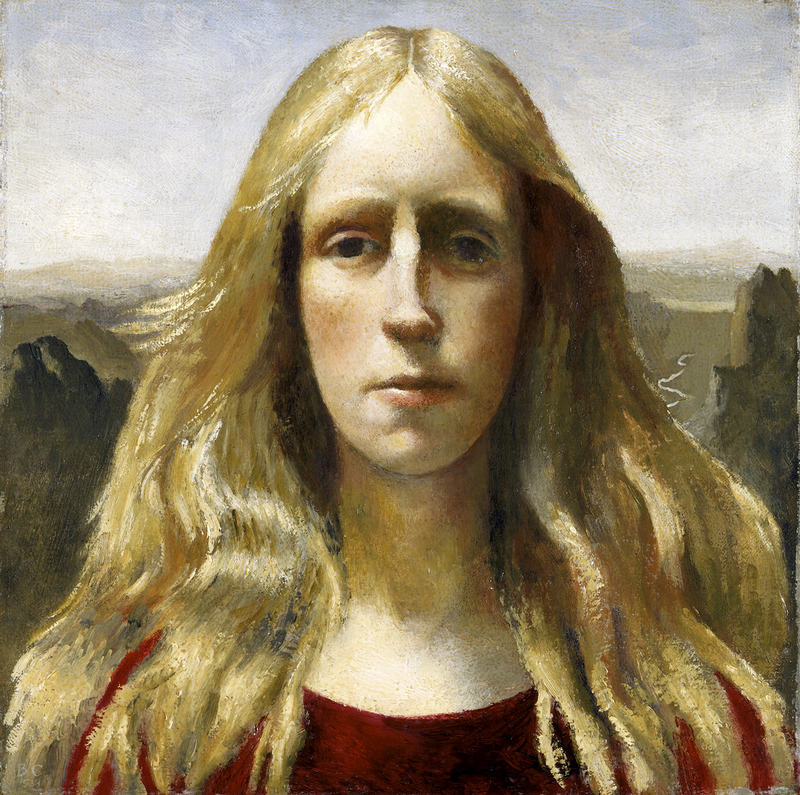

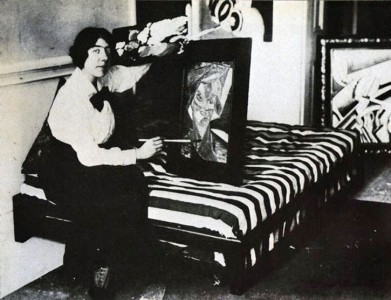

One such artist was the portraitist Flora Lion (1878–1958). She – and her genre – weathered the aesthetic storm that was Modernism but careers like Lion's illustrate how painters who sought no quarrel with tradition had to try and remain relevant.

Lion was of French and Jewish descent and lived in London. Her parents' first child, she was the only member of the immediate family to take up art, although it may be significant that the Academician Solomon J. Solomon and his sister Lily (later Lily Delissa Joseph) were amongst her many cousins. She attended St John's Wood Art School in 1894, the Royal Academy Schools from 1895 to 1899, followed by the Académie Julian in Paris from 1899 to 1900. She was taught at the Academy by John Singer Sargent, George Clausen and the aforementioned Solomon, and at Julien's by Jean-Paul Laurens.

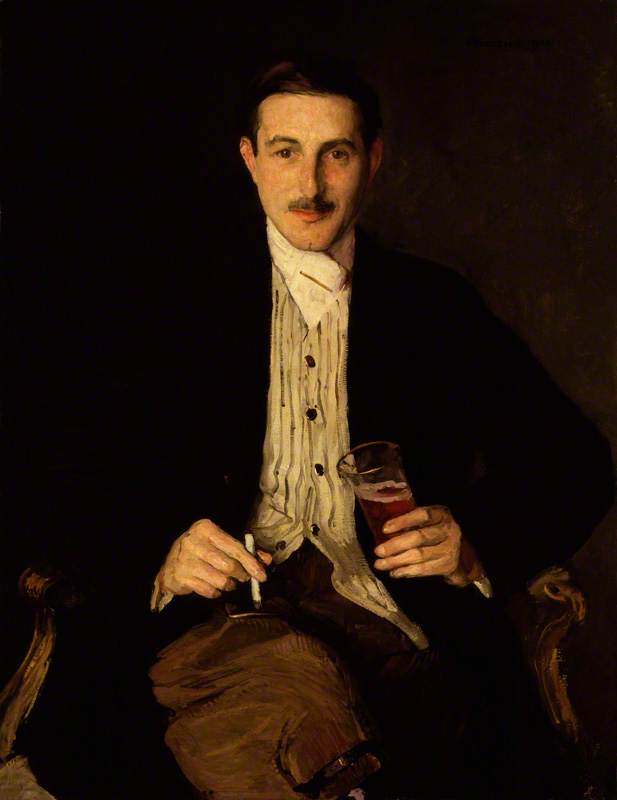

It looks as if portraiture was not necessarily Lion's aim at the outset: her first exhibition appearance was at the Royal Academy in 1900 with the Tennysonian favourite The Lady of Shallot. But on her next appearance there in 1904, she showed Yvonne, a portrait of her sister, and in the intervening years it was as a portraitist that she had success in Paris, at the 1903 Société des Artistes Français. Alfred Yockney, then in charge of the Art Journal, called her exhibit 'a capital likeness which greatly pleased the sitter and was awarded high praise from the eminent French critics.' Furthermore, 'Miss Lion is at present engaged on several portraits in Paris including one of the Baroness de Marchi and a miniature of the Marquis del Rio, a Cuban millionaire...'.

By 1906, Lion was described in the August edition of The Studio as one 'amongst women portrait painters in London [who] bids fair to come prominently to the front'. A few months later she appeared amongst the painters of the 'Exhibition of Jewish Art and Antiquities' at the Whitechapel Art Gallery.

It is of course of interest to see how Lion managed her personal identity in her professional endeavours. In a roll call of the artist's sitters, Jewish names appear alongside Gentile, forming a cross-section of middle- and upper-class British life.

Without belonging to a recognisable school or trend of contemporary art, and not inclined to confine herself to the Royal Academy, it looks as if Lion realised she needed to put herself and her work before the public as constantly and widely as possible in order to establish her name. Correspondence from 1905 indicates that her gregarious lifestyle, one which involved organising musical entertainments to which useful people, Jewish and Gentile, could be invited.

It helped that she was the cousin of a well-known painter (the aforementioned Solomon) and a friend of the portraitist John Lavery. Although these connections helped her, it was a double-edged sword for any woman artist to lean heavily on male connections, as she could be pigeonholed as a mere follower or imitator of men.

A specific example of the outcome of the networking so vital to the portraitist, in which the social and the professional, the disinterested and the commercial had to be held in a delicate balance, is Lion's lithographic portrayal of Lady Gregory, whom she 'met at lunch at Sir Hugh Lane's'. Lion made at least twenty-four of these portraits of cultural figures between 1912 and 1915, in pencil, chalk, charcoal or lithograph, perhaps as 'calling-cards' rather than on commission. Those of writers and artists were intended, according to Lion's obituary, for a publication.

Reflecting a judicious cruising of the opportunities available to her, by the end of Lion's first decade of exhibition she had been seen at the Royal Academy, the Liverpool Autumn Exhibition, the Pastel Society, the Royal Society of Portrait Painters, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the Allied Association of Artists, and in Paris. At this point, she was still interleaving her portrait exhibits with imaginative or genre compositions that fell within traditionally feminine territory, such as Motherhood and The Skylark.

Undirected by an intellectual agenda espoused by groups such as the Camden Town Group or the Vorticists, Lion may have allowed opportunity to dictate the reach and range of her practice. It can be easy to forget that the majority of artists in early twentieth-century Britain did not belong to a named tendency or group, and did not represent any 'ism'. An artist's identity was to some extent determined by the company she or he kept in exhibition, as critics tried to explain London's increasingly populous and diverse artistic scene.

Lion's visibility advanced steadily up to the outbreak of war. In 1909 she was elected to membership of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, and in 1910 to the new National Portrait Society. In that same year she was included in the Whitechapel Art Gallery's landmark exhibition 'Twenty Years of British Art' with the portrait My Mother. In 1912, this work was included in the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale, and in 1913, The Studio identified Lion as 'one of the most interesting of English women portrait painters at present exhibiting'.

Of course the war, breaking out in late 1914, threatened Lion's career, as it did for most others. It is perfectly possible that when in 1915 she married, at the conventionally late age of 37, it was a marriage of convenience – especially since she retained her family name and her husband Ralph Amato soon identified himself as her secretary and press officer. Lion hustled for government commissions along with dozens of other artists trying to maintain their incomes. Business became harder as the conflict dragged on, though in May 1916 her work was included in an exhibition whose purpose was 'to create a fund to assist women artists who are sufferers by the War'. Other exhibitors included painters of equal or greater fame such as Annie Swynnerton, Hilda Fearon and Laura Knight.

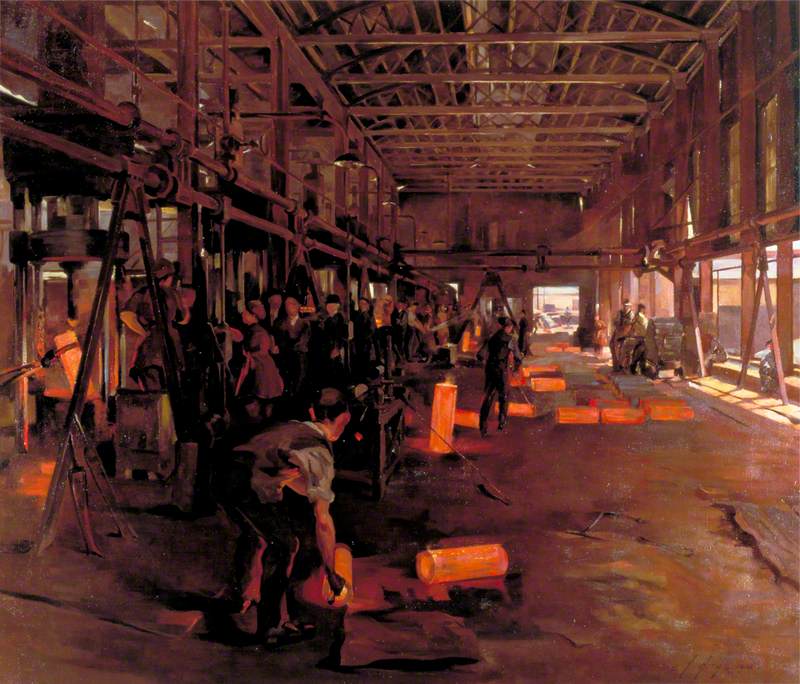

Neither the Imperial War Museum nor the Ministry of Information was inclined to buy Lion's ambitious compositions Women's Canteen at Phoenix Works, Bradford and Building Flying Boats, and she showed the two redundant canvases around the country between 1918 and 1922, perhaps thinking to expand her public image beyond portraiture.

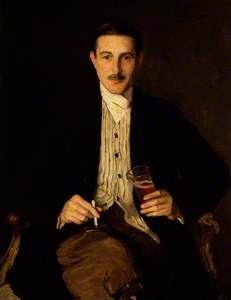

By 1923, a commentator on British art declared that 'Portraiture, in which the human body is represented with the added interest of personality, has for the most part sunk to the level of a trade. Instead of ranking with the other branches of graphic art, it enters into competition with the fashionable photograph.' That year Lion's first solo exhibition, at London's Alpine Club, was clearly a concerted attempt to rebuff this perception, featuring numerous aristocrats, society ladies and other people in the public eye including the Marchioness of Tweeddale, the writer Gilbert Frankau and Mrs Ralph Peto.

Royalty was her next 'catch', as reported by critic Frank Rutter two years later: 'A woman painter who has come rapidly to the fore during recent years is Mrs Flora Lion, whose portrait group of the Duchess of York and her sisters attracted much attention in last year's Academy. Since then, Mrs Lion has been in the United States, where she has painted a number of portraits and met with much appreciation. Swift to read character, quick to grasp a picturesque pose or a decorative arrangement, and gifted with the facility of being able to fix her vision deftly with a flowing brush, Mrs Lion is a born portrait painter who cannot fail to succeed in her metier.'

This range of crowd-pleasing sitters continued, with an emphasis on titled men and women and cultural figures such as pianist Mathilde Verne and entertainer Charlotte Greenwood. This practice ensured regular appearances at the Royal Academy exhibition, which were rounded out with solo shows in 1937, 1940 and 1942, the second of these boasting a portrait of the Queen as its headline work.

Other subjects of public interest painted by Lion included the former suffragist Flora Drummond and conductor Sir Henry Wood. Another of the exhibits in this show, Mrs Hunter Crawford, attracted the gold medal of the Société des Artistes Français in 1949.

Flora Lion can be seen, then, as a survivor in testing times, even though she is nowadays an obscure figure. Her adroit negotiation of the challenges of Modernism and of the sociological changes especially relevant to portraiture enabled her to paint up until her death in 1958. The standing of a portrait is traditionally strongly linked to the identity of its subject, but even the anonymous Portrait of a Lady (c. 1907) shows that Lion was a painter of distinction. Her substantial body of work can be only glimpsed in our public collections but is worth seeking out.

Pamela Gerrish Nunn, art historian