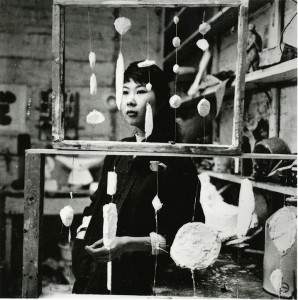

In 1971 the Tate Gallery ran a major retrospective of the artist and sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005). He was aged just 47, but it was fitting recognition for someone who had represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1960, shown with Giacometti in New York, and had multiple works in British and American museum collections.

Born in Scotland to Italian parents, moving to England to study and work, Paolozzi had been on a fast track since London's prestigious Mayor Gallery gave him a solo show in 1947 while he was still an art student.

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005)

1987

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

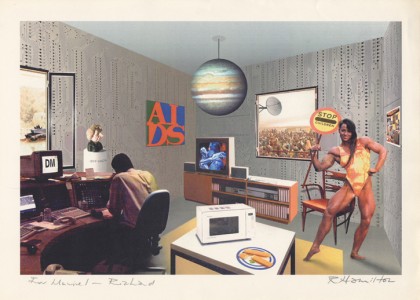

The Tate today lists a startling 437 works by Paolozzi, from the witty and colourful collages from the 1940s that won him the place as a father of pop art to signature sculptures from the 1950s to the 1980s. The gallery received a huge gift of material from Paolozzi's archive in 2014. But the 1971 show says art historian Dr Judith Collins, currently working on the artist's first catalogue raisonné of his metal works, was 'a disaster'.

'He criticised the current art of other artists, he criticised Cy Twombly, he criticised American art. The reviews of the Tate retrospective were very fierce, saying he had lost his way,' she said.

'He was thought of as a pop artist and he didn't know what to do with himself because he wasn't a pop artist. It was a disaster for him, then Germany saved him, and Scotland saved him. Germany gave him massive public monuments to build and then Scotland thought oh, he's pretty good, he can be our sculptor-in-ordinary.'

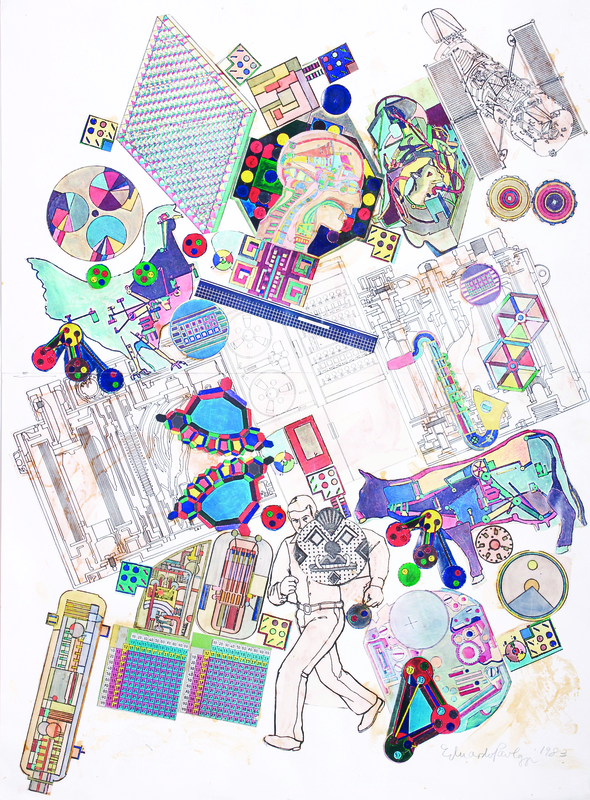

Paolozzi spoke of how he was inspired by The Mummy's Hand and Boris Karloff in Frankenstein. He used wax impressions of radio parts, clock workings and toys.

Paolozzi was born in Leith, the port serving Edinburgh, where his immigrant parents ran an ice-cream parlour – the trade dominated by Italian families in Scotland, who also commonly ran its best fish and chip shops. His father, an admirer of Mussolini who sent Eduardo to a fascist youth camp in Italy, drowned along with Paolozzi's grandfather with the sinking of the SS Arandora Star. Carrying Italian internment prisoners bound for Canada, it was sunk by a U-boat in 1940, with the loss of more than 800 lives. Would one call Paolozzi Scottish-Italian today? He moved to London as a young man and his studio was in Chelsea.

The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh houses Paolozzi's reconstructed studio. It's a sanctuary for Paolozzi aficionados, and represents how this shambling, expansive, big-handed sculptor would seem to gather everything in his way – books, toys, machine parts.

But further south, London is an unfolding treasure trove for a lover of Paolozzi. They turn up in surprising places, with a warmth of recognition, the sense of a secret shared. En route to a ward in the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, there's a double-take over the robotic figure near the revolving doors, with a scattering of notes inside its square glass tummy. Passers-by could take it for a fairground toy, with a crane to fish for gifts, or a jingle of change if you shake the outstretched hand. It's Paolozzi's Healing Arts Collection Box, part of the hospital's richly varied art collection.

There's another Paolozzi inside the Queen Elizabeth Hall: On This Island (after Benjamin Britten Op. 11) in the Government Art Collection, which the Paolozzi Foundation paid to be restored.

On This Island

(after Benjamin Britten Op. 11) 1985–1986

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

Art writers and bloggers from time to time 'discover' the London Paolozzis, like the Londonist in 2017. Perhaps because a passion for this particular artist can creep up unawares; suddenly, you realise you're a Paolozzi fan. But it's also because of his uncertain legacy, underlined in the response to the Tate retrospective. Paolozzi first emerged as a pioneer of pop art with the quirky, colourful collages that delightfully skewered post-war modernity. His output was prodigious, but his poor relations with dealers, and his generosity with friends, meant his market was unmanaged. His wood and plaster pieces may never be accurately tallied.

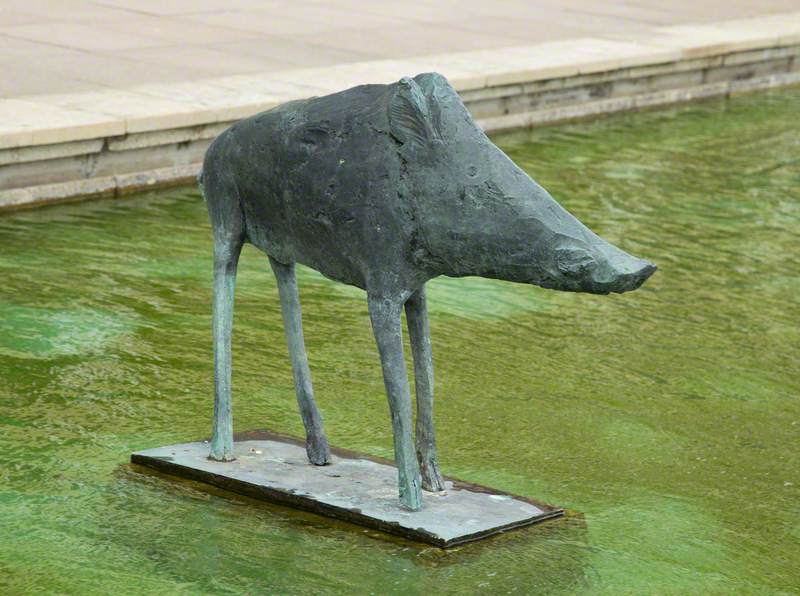

Paolozzi's work in the capital reflects that legacy: they are often commissions of the late 1980s and 1990s, when his British reputation had begun to recover. The mechanical character of these later works, monumental metal pieces, echo a singular style that is easy to spot, but blend easily into an urban landscape. The queue at the annual orchid festival at Kew snakes past the reclining figure of A Maximis Ad Minima in the rain, with its displaced iron arms like a Picasso. Would visitors, who'd remark on a Henry Moore figure, register the Paolozzi as more than a curiosity? Most probably, if at all, as the man who 'did that piece at the British Library'.

But there's no better time to revisit the London Paolozzis, and with an extra twist or two. 'Eduardo Paolozzi: Hollow Gods', an exhibition at the private Hazlitt Holland-Hilbert Gallery in St James, opened in October and runs until mid-December 2019.

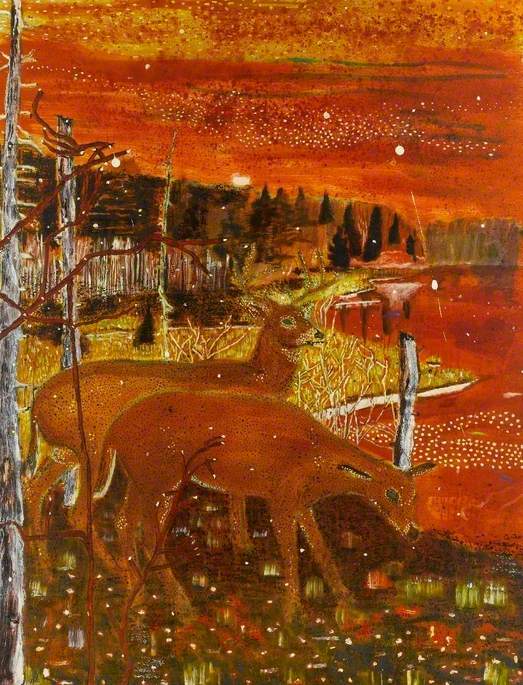

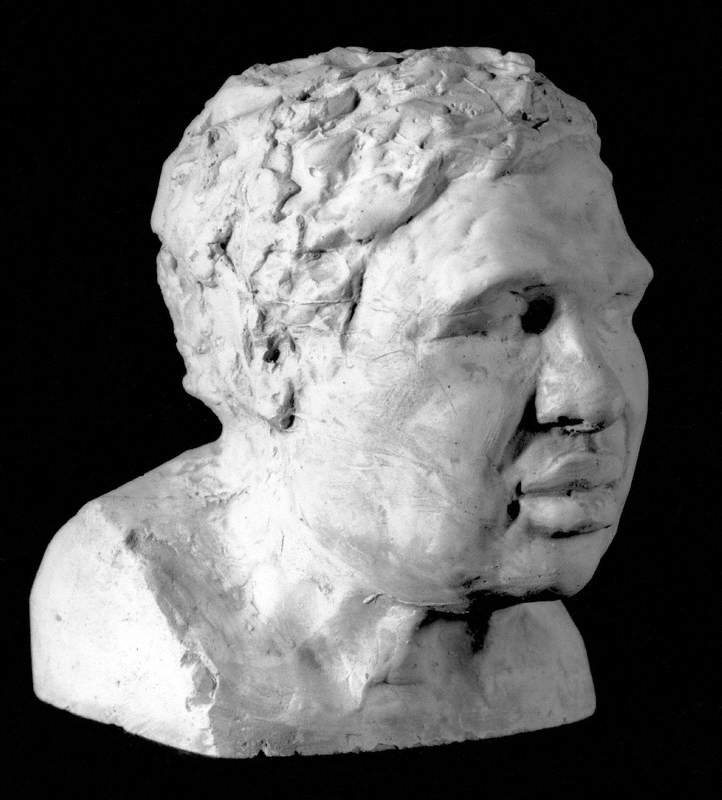

The gallery is taking over the running of Paolozzi's estate, with a mission to raise his profile, and this is the first in a series of planned shows. The exhibition – curated by Dr Collins – turns on his work from the late 1940s to 1960, with a series of powerful 1950s sculptures: brooding figures of rough handmade detail radically different from the later public commissions, which are silky smooth by comparison. Most are on loan rather than for sale; some unseen for 50 years.

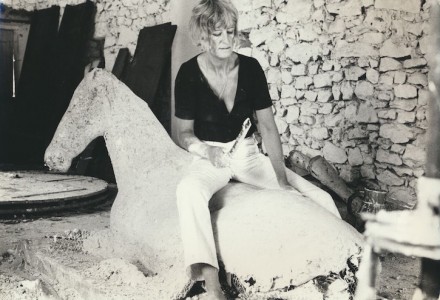

The works come from the period when Paolozzi handmade his sculptures in wax – colossal figures as big as a man, which were then sent to the foundry. Paolozzi spoke of how he was inspired by The Mummy's Hand and Boris Karloff in Frankenstein. He used wax impressions of radio parts, clock workings and toys. Machines and fantasy, he said, went together. His favourite museums were the Imperial War Museum, the Science Museum, and the Natural History Museum.

Over at Tate Britain, if you're in a Newton frame of mind, the epochal William Blake show running until February 2020 shows Blake's original Newton. There are 13 sombre portrait paintings of Isaac Newton listed on Art UK, but Blake's famous colour print is the young, preternaturally muscular, game-changing god.

It is the naked, sinewy figure whom Paolozzi transformed into a slow-moving, thick-thighed mechanical giant, in surely his most familiar work, in the courtyard of the British Library. Paolozzi's Newton is an example of the later work he made directing engineers – they are entirely different from the much darker 1950s pieces.

Much lesser known is another Newton in the Royal Society, also on Art UK.

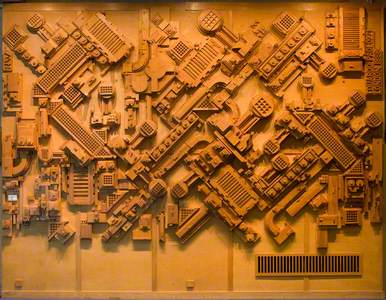

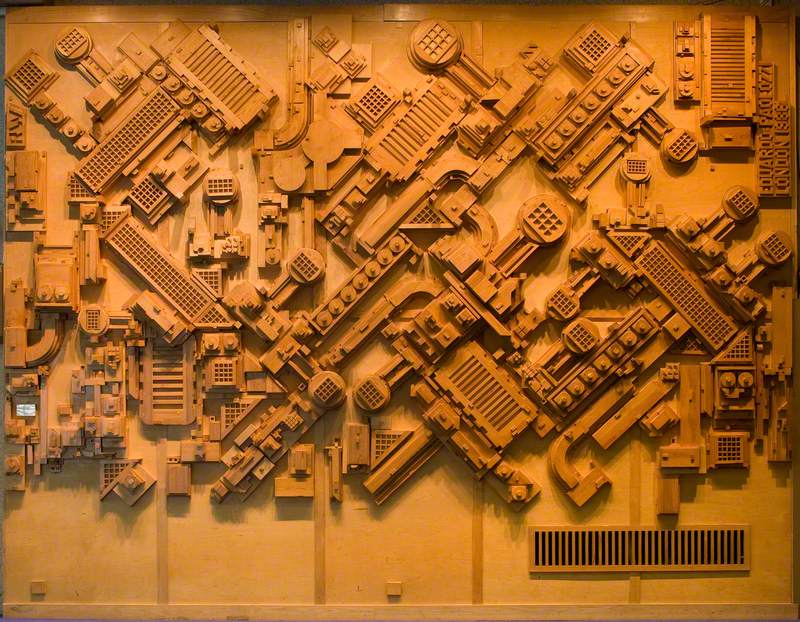

Aside from Newton, Paolozzi's most famous London monument are the Tottenham Court Road tube station mosaics, covering 950 square metres, completed in 1986 and restored in 2017.

Tottenham Court Road Underground

1987

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

Tottenham Court Road Underground Station Mosaic Study: Running Man

1983

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

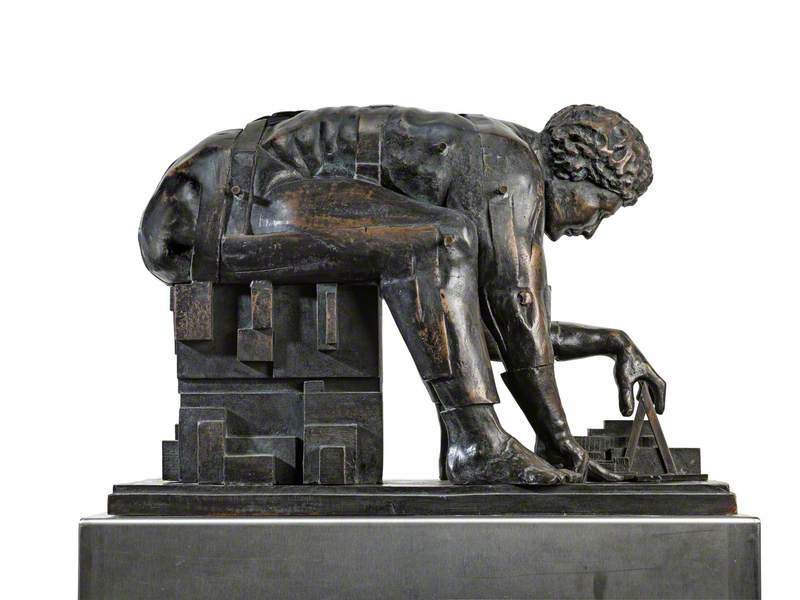

Before their restoration, the tube mosaics had been overlooked, even neglected – perhaps indicative of Paolozzi's London works. One prominent London Paolozzi was even removed. In 1987 the London and Paris Property Group commissioned The Artist as Hephaestus, and built a special niche for the work into the façade of its High Holborn headquarters.

It was sold after a refurbishment of the building for £110,500 at Bonham's in 2014, though two versions of it are now in the National Portrait Gallery – a smaller bronze version was bought in 1987, and Paolozzi gave a plaster and polystyrene version to the Gallery in 1990.

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005)

1987

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

The original Hephaestus was put up for auction twice, reflecting Paolozzi's uncertain market position.

In his early career critics called Paolozzi the 'most positive and original sculptor' of his generation in Britain. But the artist has been long undervalued, in the eyes of his admirers. His auction record remains a modest £120,000, though works have earned higher prices in the private market, with classic collages reportedly priced for up to £100,000, and sculpture well over £1 million.

Whatever the future for Paolozzi in the auction room, his works will remain in prominent places up and down the country – keep watching Art UK as more sculptures are added to the site.

Tim Cornwell, freelance arts writer