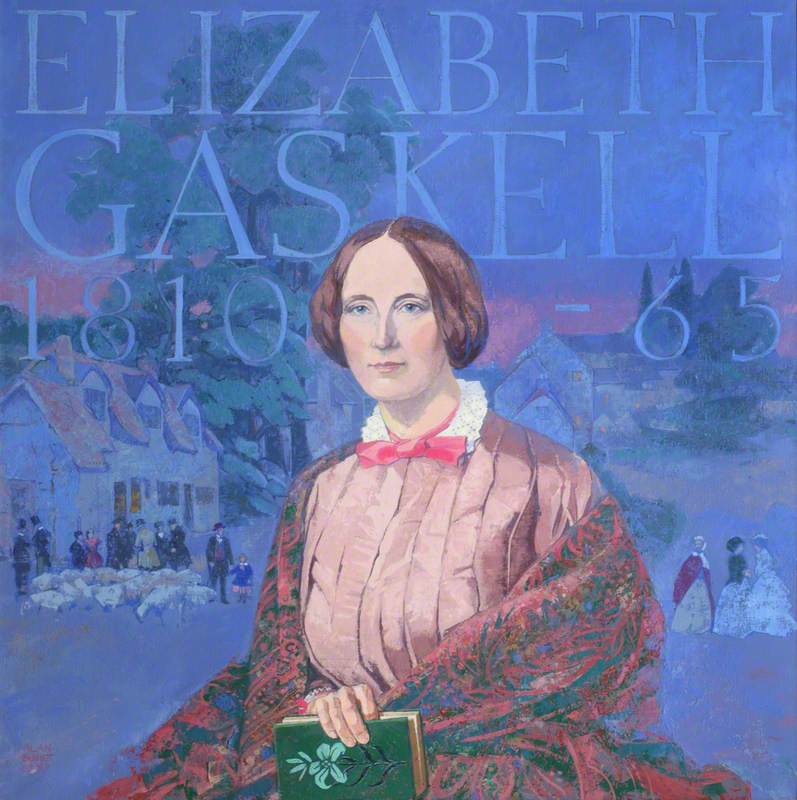

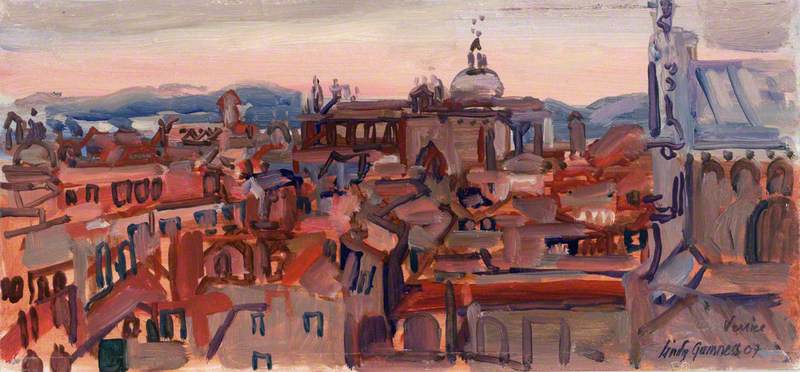

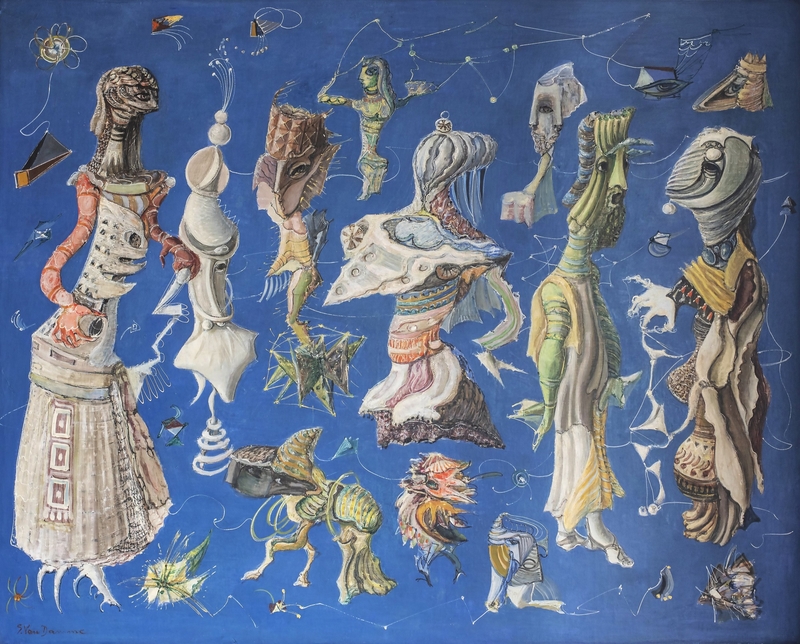

The exhibition 'Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900–1950' is showing at The Ambulatory at the Mercers' Company from 3rd December 2018 to 23rd March 2019, and at The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery,

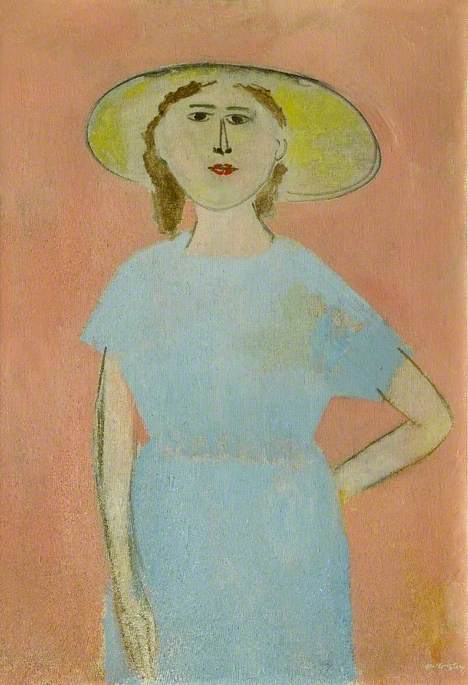

Ever since Linda Nochlin asked in 1971, 'Why have there been no great women artists?', art history has been probing the female gaze. Through scholarship and exhibitions, readings have been put in place to counter prevailing assumptions that artistic creativity is primarily a masculine affair.

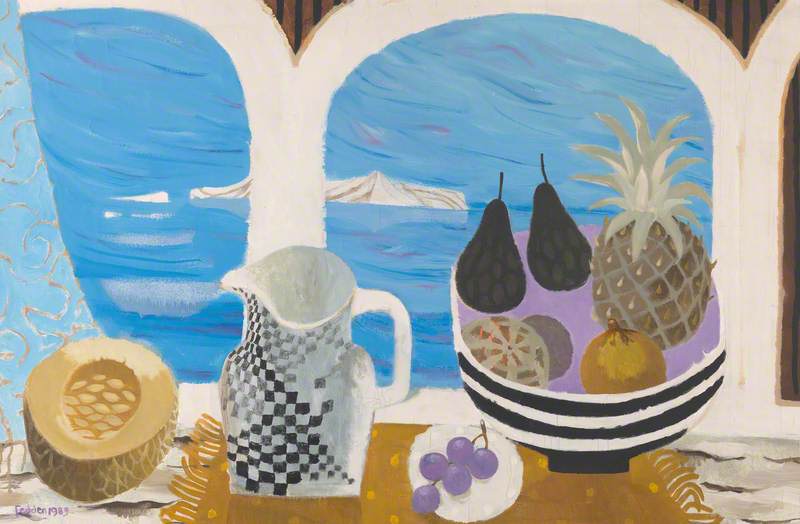

The exhibition '50/50; Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900–1950' functions as a corrective to the exclusion of women from the 'master' narratives of art. It introduces fifty artworks by known and lesser-known women – outstanding works that speak out.

Fifty Works by Fifty British Women Artists 1900–1950

Edited by Sacha Llewellyn

First opened in December 2018 at Mercers Hall in the City of London, and touring to the Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery at Leeds University in April 2019, the exhibition celebrates and ensures the legacy of an important centenary, the 1918 Representation of the People's Act, which gave women over the age of 30 the right to vote.

The act of reinserting lost voices – reclaiming their historical presence and documenting their output – is essential for the past and future status of female artists.

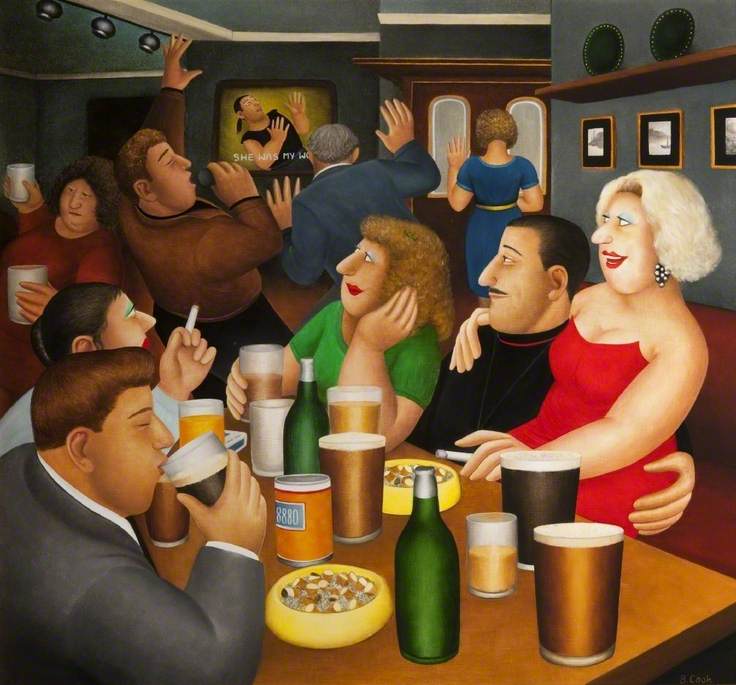

Women artists have been set apart from male artists not only to their own disadvantage but also to the detriment of British art. While there were some improvements to women's access to an artistic career in the twentieth century, in terms of encouragement, patronage, economics and critical attention (all the things that confer professional status), women had the least of everything. By showcasing just a few of the remarkable works produced by women, '50/50' draws attention to the fact that a vision of British twentieth-century art closer to a 50/50 balance would not only provide a truer account, but also a more vivid and meaningful narrative.

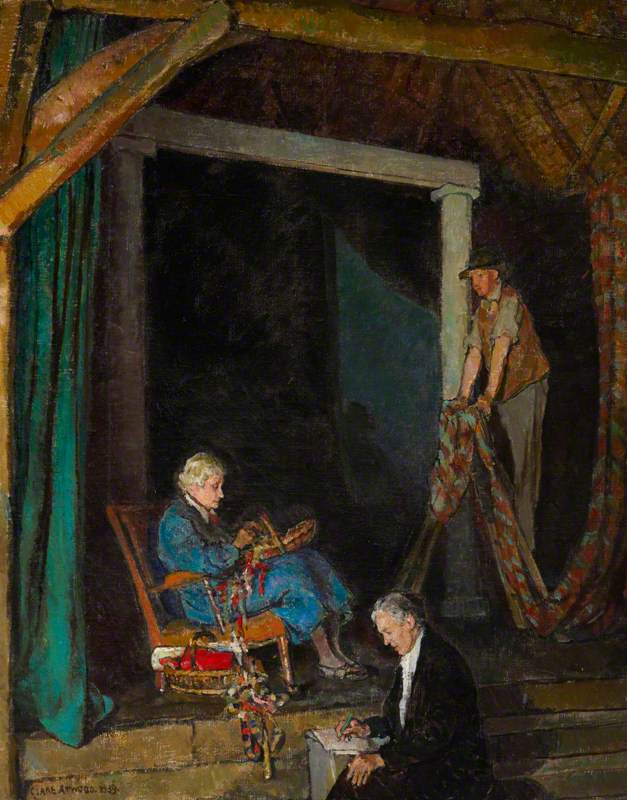

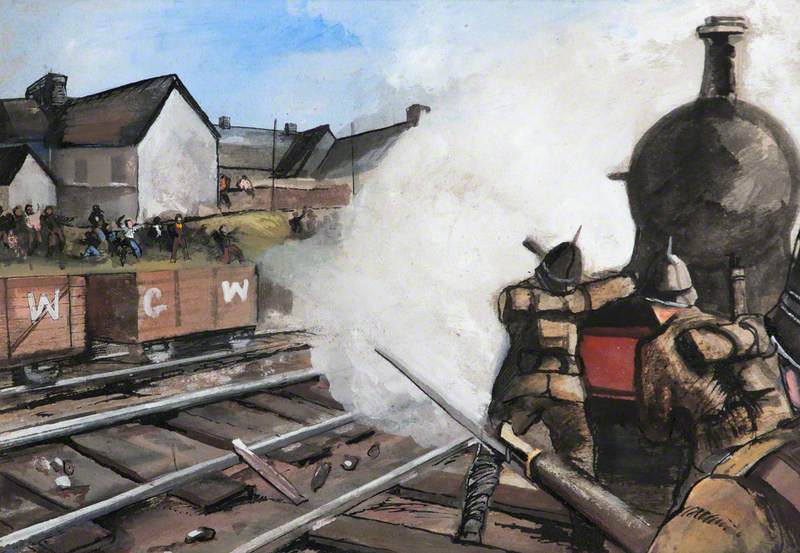

The exhibition surprises with its artistic revelations and annuls any notion that women, although they may share the same obstacles, necessarily paint alike. Through portraits and self-portraits, landscapes and cityscapes, industrial scenes and images of war, the exhibition

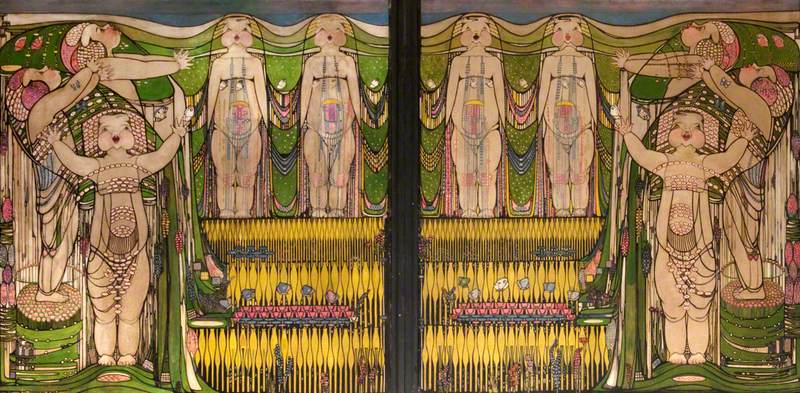

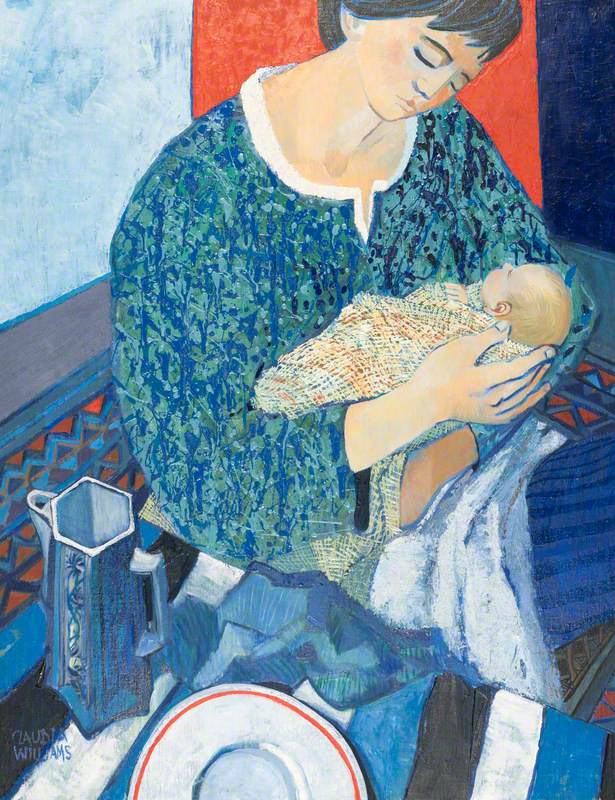

Romance – Cecile Walton (1891–1956), with her Children Edward and Gavril

1920

Cecile Walton (1891–1956)

Lying on a chaise longue in an arrangement reminiscent of Édouard Manet's Olympia (1865), but holding a baby and with her space invaded by domestic obligations, Walton is a mother and a muse before she is a painter.

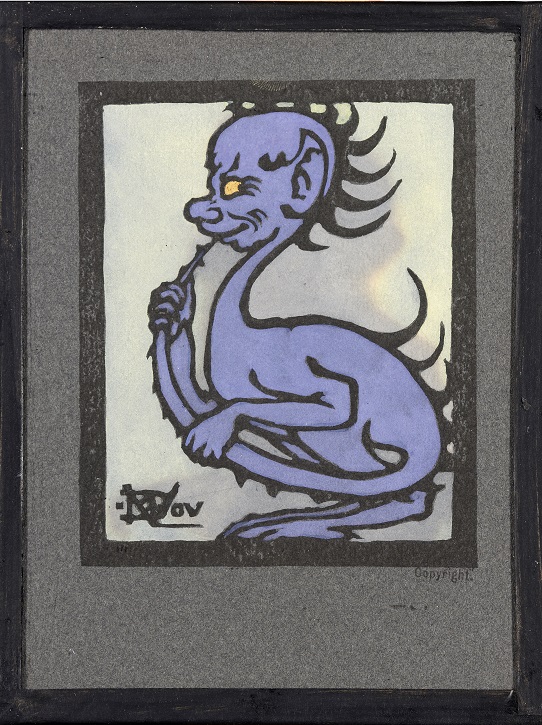

A Sleeping Demon (purple) from 'Devils in Diverse Shapes'

c.1906, hand-coloured woodcut by Marion Wallace Dunlop (1864–1942)

Indeed, it was perhaps the moments of adversity and contradiction in their professional lives that led so many women artists to engage with the politics of their day. Marion Wallace Dunlop's radical protests for the women's suffrage movement – including the first hunger strike campaign – illuminates her Devils in Diverse Shapes (1906).

Portrait of a Jewish Refugee

c.1939, oil on canvas by Phoebe Willetts-Dickinson (1917–1978)

Phoebe Willetts-Dickinson's wartime paintings of refugees gave way in the post-war era to more overtly political subjects such as Holloway Prison, recording her six-month incarceration for civil disobedience. Women artists also responded to both World Wars differently than men; 'the preposterous male fiction' – to quote Virginia Woolf – designated women as other, and the work they produced encapsulates something distinct from that of their male contemporaries. As non-combatants, they recorded life on the Home Front as well as in clearing stations and hospitals closer to the battlefields.

Olive Mudie-Cooke's vivid scenes of the work of nurses and medical staff in France and Italy during the First World War portray a wartime landscape that women transgressed into and rendered more humane. Evelyn Dunbar, the only salaried woman artist during the Second World War, produced a series of pictures of female workers conveyed with dignity and strength as they adapted to the harsh reality of their changing lives.

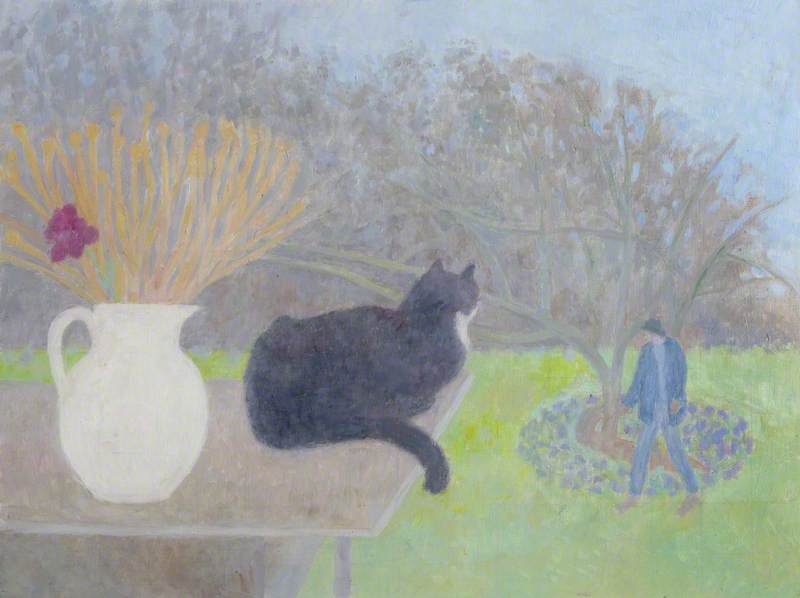

Milking Practice with Artificial Udders

1940

Evelyn Mary Dunbar (1906–1960)

Women's art has been out of sight and out of mind for too long. Art Uk's initiative of putting oil paintings in public collections on to their platform has marked a watershed in the study of women artists. In the past, if you wanted to view two of the star paintings in this exhibition, a trip to the Jerwood Gallery at Hastings would have been called for – with the added frustration that, as museums cannot show everything they own at any one time and women's art is all too often sidelined, the pictures may not have been on display.

In addition, with only 3 to 5 per cent of works in major permanent collections in the US and Europe (statistic from National Museum of Women in the Arts) by female artists, giving visibility to these artworks is only a start. The act of reinserting lost voices – reclaiming their historical presence and documenting their output – is essential for the past and future status of female artists.

As Virginia Woolf wrote in A Room of One's Own (1929), 'if

Sacha Llewellyn, Liss Llewellyn Fine Art

.jpg)