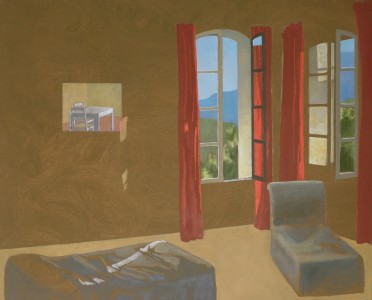

The living room is sparsely furnished: a white coffee table with a book on top, a shagpile carpet, a picture frame. The only ornamental elements are a vase of lilies on the table and a lampshade on the floor. Sunlight bursts into the room through the half-open shutters of a tall window.

On either side of the window are Mr and Mrs Clark. She has curly ash-blonde hair and stands, hand on hip, in a burgundy caftan, smiling faintly. He slouches in the chair, cigarette in hand, gazing obliquely at the viewer; his bare feet are buried in the carpet, and a white cat sits in his lap.

Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1970–1971) is one of David Hockney's best-known paintings: part of a series of double portraits that he made in the 1960s and 70s that catapulted him to international fame. It's a painting I love, without being completely able to explain why. I see the picture every time I reach for a pint of milk, on a magnet stuck to my fridge.

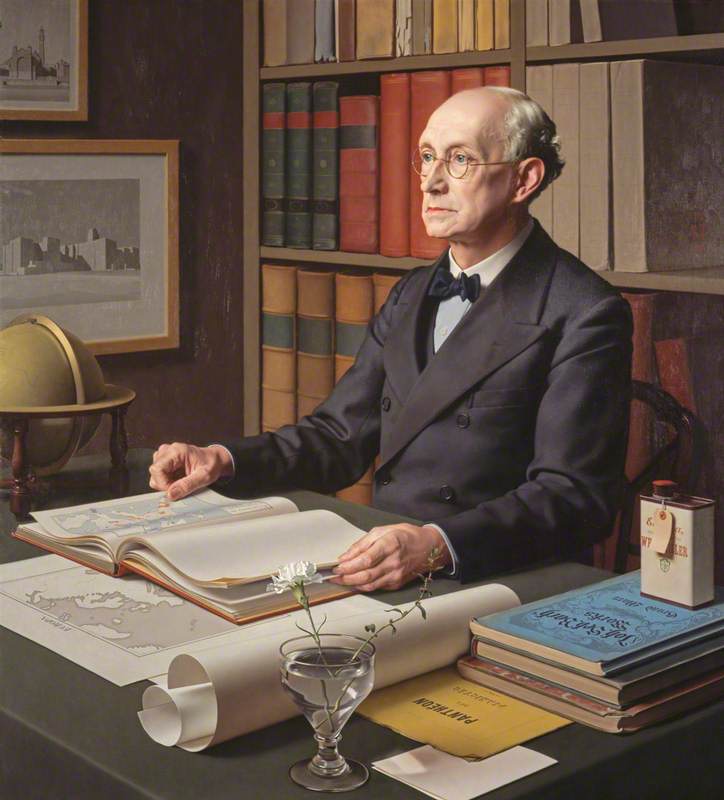

It recalls an even more mysterious painting that captured my attention as a little girl, and which Hockney clearly drew inspiration from: Jan van Eyck's 'Arnolfini Portrait', in which a woman in an elaborate green gown holds hands with a man in a fur cape and a wide-brimmed hat.

Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife

1434

Jan van Eyck (c.1390–1441)

Yet the Clarks are nowhere near as loved-up as the Arnolfinis; they seem estranged from each other, on parallel tracks.

What makes Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy such a landmark, I think, is the expression on Mrs Clark's face. It's full of humanity and innocence, full of soul. Her husband looks aloof by comparison, and not in tune with her emotions. He sits, she stands. His leg is outstretched, and he has a swagger about him. The half-open window casts a wall of light between them, splitting the canvas in two. And, as the description on the Tate website tells us, their marriage dissolved soon afterwards.

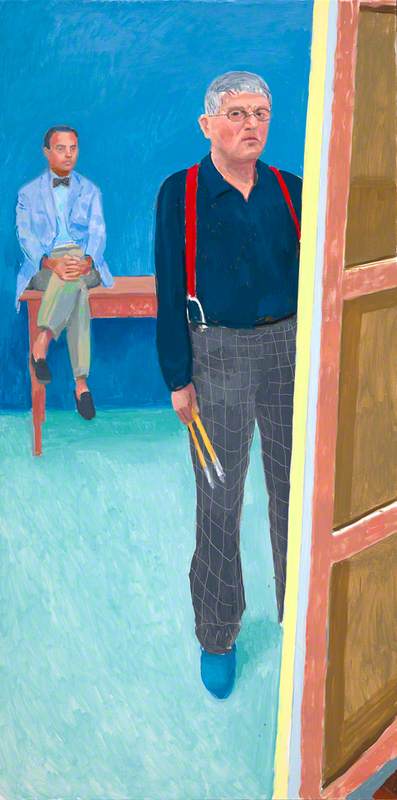

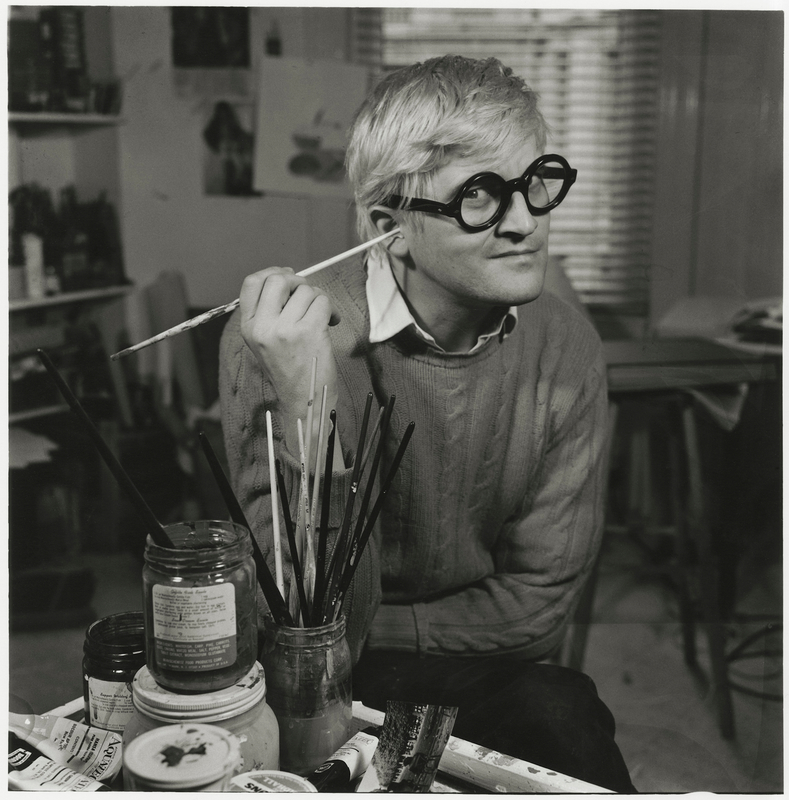

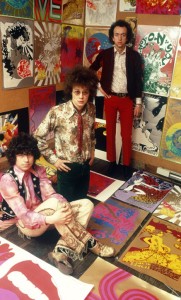

I've had the opportunity to interview David Hockney on a few occasions in London. He has the endearing and avuncular manner of a Yorkshireman, and, despite decades of life in California, still speaks with a northern accent. He also has the self-assuredness that artists have: a prominent sense of self, a noticeable ego.

I once asked him about Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy. He acknowledged that it was a 'memorable picture', of which he had painted quite a few. 'But no one knows what makes it a memorable picture', he noted. 'If they did, there would be a lot more.' The picture took a year to complete, he said – 'the hair on Celia took a long time! Little ringlets!'

Celia Birtwell (a.k.a. Mrs Clark), who I also interviewed once, had her own story to tell. She said Hockney came to Linden Gardens, where the couple had a first-floor apartment. He decided the best light was in the bedroom, so he transformed the bedroom, and constructed a set. He picked objects he found around the house – the cream-coloured telephone, the white lilies – and took lots of pictures. He also renamed the cat: the one in the picture was actually named Blanche, and she was Percy's mother.

The story behind the painting is, of course, fascinating in a purely anecdotal, tabloid-y way. Yet Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy is much more than the sum of its parts. It is a memorable picture, as Hockney says. In the Hockney retrospective held in London, Paris, and New York in 2017–2018, the picture was a highlight of the spectacular room of double portraits. Future art historians will no doubt identify it as a masterpiece. In the meantime, it lives, in miniature form, on my fridge door.

Farah Nayeri, writer